Приблизительное время чтения: 20 мин.

Крещение Господне, или Богоявление, православные христиане празднуют 19 января. В этот день Церковь вспоминает евангельское событие — как пророк Иоанн Предтеча крестил Господа Иисуса Христа в реке Иордан. Мы расскажем об истории, традициях и смысле праздника.

Что такое Крещение Господне

Крещение Господа Бога и Спаса нашего Иисуса Христа — один из важнейших христианских праздников. В этот день христиане всего мира вспоминают евангельское событие — крещение Иисуса Христа в реке Иордан. Крестил Спасителя пророк Иоанн Предтеча, которого также называют Креститель.

Второе название, Богоявление, дано празднику в память о чуде, которое произошло во время крещения. На Христа с небес сошел Дух Святой в облике голубя и глас с неба назвал его Сыном. Евангелист Лука пишет об этом: Отверзлось небо, и Дух Святый нисшел на Него в телесном виде, как голубь, и был глас с небес, глаголющий: Ты Сын Мой Возлюбленный; в Тебе Мое благоволение! Так была явлена в видимых и доступных для человека образах Святая Троица: голос — Бог Отец, голубь — Бог Дух Святой, Иисус Христос — Бог Сын. И было засвидетельствовано, что Иисус — не только Сын Человеческий, но и Сын Божий. Людям явился Бог.

Крещение Господне — двунадесятый праздник. Двунадесятыми называются праздники, которые догматически тесно связаны с событиями земной жизни Господа Иисуса Христа и Богородицы и делятся на Господские (посвященные Господу Иисусу Христу) и Богородичные (посвященные Божией Матери). Богоявление — Господский праздник.

Когда празднуется Крещение Господне

Крещение Господне Русская Православная Церковь празднует 19 января по новому стилю (6 января по старому стилю).

Праздник Богоявления имеет 4 дня предпразднства и 8 дней попразднства. Предпразднство – один или несколько дней перед большим праздником, в богослужения которого уже входят молитвословия, посвященные наступающему празднуемому событию. Соответственно, попразднство — такие же дни после праздника.

Отдание праздника совершается 27 января по новому стилю. Отдание праздника — последний день некоторых важных православных праздников, отмечаемый особым богослужением, более торжественным, чем в обычные дни попразднства.

События Крещения Господня

После поста и странствий в пустыне пророк Иоанн Предтеча пришел на реку Иордан, в которой иудеи традиционно совершали религиозные омовения. Здесь он стал говорить народу о покаянии и крещении во оставление грехов и крестить людей в водах. Это не было Таинством Крещения, каким мы его знаем сейчас, но было его прообразом.

Народ верил пророчествам Иоанна Предтечи, многие крестились в Иордане. И вот, однажды к берегам реки пришел сам Иисус Христос. В ту пору Ему было тридцать лет. Спаситель попросил Иоанна крестить Его. Пророк был удивлен до глубины души и сказал: «Мне надобно креститься от Тебя, и Ты ли приходишь ко мне?». Но Христос уверил его, что «надлежит нам исполнить всякую правду». Во время крещения отверзлось небо, и Дух Святый нисшел на Него в телесном виде, как голубь, и был глас с небес, глаголющий: Ты Сын Мой Возлюбленный; в Тебе Мое благоволение! (Лк 3:21-22).

Крещение Господне было первым явлением Христа народу Израиля. Именно после Богоявления за Учителем последовали первые ученики — апостолы Андрей, Симон (Петр), Филипп, Нафанаил.

В двух Евангелиях — от Матфея и Луки — мы читаем, что после Крещения Спаситель удалился в пустыню, где постился сорок дней, чтобы подготовиться к миссии среди людей. Он был искушаем от диавола и ничего не ел в эти дни, а по прошествии их напоследок взалкал (Лк. 4:2). Диавол три раза подступал ко Христу и искушал Его, но Спаситель остался крепок и отринул лукавого (так называют диавола).

Что можно есть на Крещение Господне

Поста в праздник Крещения нет. А вот в Крещенский Сочельник, то есть накануне праздника, православные соблюдают строгий пост. Традиционное блюдо этого дня — сочиво, которое готовят из крупы (например, пшеницы или риса), меда и изюма.

Крещение Господне — история праздника

Крещение Господне начали праздновать, еще когда были живы апостолы — упоминание об этом дне мы находим в Постановлениях и Правилах апостольских. Но поначалу Крещение и Рождество были единым праздником, и назывался он Богоявление.

Начиная с конца IV века (в разных местностях по-разному) Крещение Господне стало отдельным праздником. Но и сейчас мы можем наблюдать отголоски единства Рождества и Крещения — в богослужении. Например, у обоих праздников есть Навечерие — Сочельник, со строгим постом и особыми традициями.

В первые века христианства на Богоявление крестили новообращенных (их называли оглашенными), поэтому этот день часто называли «днем Просвещения», «праздником Светов», или «святыми Светами» — в знак того, что Таинство Крещения очищает человека от греха и просвещает Светом Христовым. Уже тогда была традиция освящать в этот день воды в водоемах.

Подробнее здесь

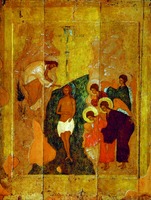

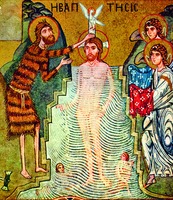

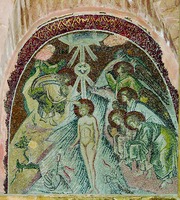

Иконография Крещения Господня

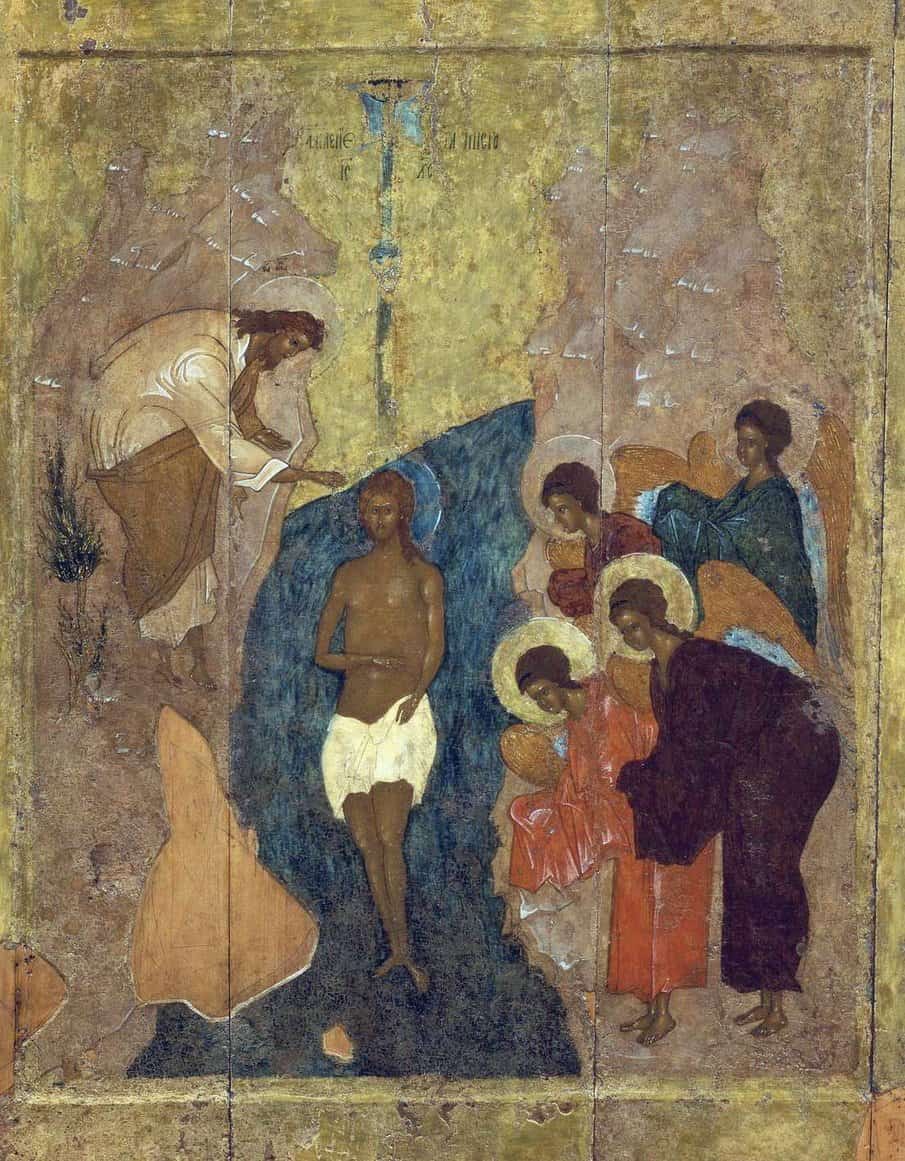

На раннехристианских изображениях событий Крещения Господня Спаситель предстает перед нами юным и без бороды; позднее Его стали изображать взрослым мужчиной.

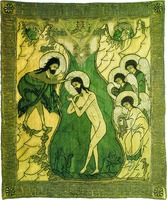

С VI-VII веков на иконах Крещения появляются изображения ангелов — чаще всего их три и они стоят на противоположном от пророка Иоанна Предтечи берегу Иордана. В память о чуде Богоявления над стоящим в воде Христом изображают островок неба, из которого к Крещаемому нисходит голубь в лучах света — символ Святого Духа.

Центральные фигуры на всех иконах праздника — Христос и Иоанн Креститель, который возлагает десницу (правую руку) на голову Спасителя. Десница же Христа поднята в благословляющем жесте.

Особенности богослужения Крещения Господня

Духовенство в праздник Крещения Господня облачено в белые ризы. Главная особенность богоявленского богослужения — это освящение воды. Воду освящают два раза. Накануне, 18 января, в Крещенский сочельник — Чином Великого освящения воды, который еще называют Великой агиасмой. И второй раз — в день Богоявления, 19 января, на Божественной литургии.

Первая традиция восходит, скорее всего, к древнехристианской практике крещения оглашенных после утренней службы Богоявления. А вторая — связана с обычаем палестинских христиан шествовать в день Богоявления на Иордан к традиционному месту крещения Иисуса Христа.

Подробнее здесь

Молитвы Крещения Господня

Тропарь Крещения Господня

глас 1-й

Во Иордане крещающуся Тебе, Господи, Троическое явися поклонение: Родителев бо глас свидетельствовавше Тебе, возлюбленнаго Тя Сына именуя, и Дух в виде голубине, извествоваше словесе утверждение. Явлейся, Христе Боже, и мир просвещей, слава Тебе.

Перевод:

Когда Ты, Господи, крестился во Иордане, явилось поклонение Пресвятой Троице, ибо глас Отца свидетельствовал о Тебе, называя Тебя возлюбленным Сыном, и Дух, явившийся в виде голубя, подтвердил истинность этого слова. Христе Боже, явившийся и просветивший мир, слава Тебе!

Кондак Крещения Господня

глас 4-й

Явился еси днесь вселенней, и свет Твой, Господи, знаменася на нас, в разуме поющих Тя: пришел еси и явился еси Свет неприступный.

Перевод:

Явился Ты ныне всему миру; и Твой свет, Господи, запечатлелся на нас, сознательно воспевающих Тебя: «Ты пришел и явился, Свет неприступный!»

Величание Крещения Господня

Величаем Тя, Живодавче Христе, нас ради ныне плотию крестившагося от Иоанна в водах Иорданских.

Перевод:

Прославляем Тебя, Христе, Податель жизни, за то, что Ты ныне для нас крестился плотию от Иоанна в водах Иордана.

Богоявленский Кафедральный Собор в Елохово

Богоявленский Кафедральный Собор находится в Москве, на Спартаковской улице, 15, недалеко от метро «Бауманская». В XIV-XVII веках здесь располагалось село Елох.

Во второй половине XV века в приходе местной церкви Владимирской иконы Божией Матери родился знаменитый московский святой — Василий Блаженный.

В то время Богоявленский собор был обычной сельской церковью. В 1712-1731 годах его перестроили в камне, кирпич на него пожаловал лично император Петр I. Освятили новое здание в 1731 году.

В конце XVIII века прихожанами Богоявленского храма стала семья Пушкиных. Известно, что великий поэт родился в Немецкой слободе и был крещен в старом Богоявленском соборе в 1799 году. Восприемниками были бабушка, Ольга Сергеевна, урожденная Чичерина, и граф Воронцов, внук замученного при Бироне министра Артемия Волынского.

Старый петровский собор простоял до середины XIX века столетия. В 1830-х годах заказ на его перестройку получил прославленный московский архитектор Евграф Тюрин. Обновленный собор освятили в 1853-ем.

В годы советской власти храм не закрывался. В праздник Сретения в 1925 году торжественную Литургию в нем служил Святейший Патриарх Тихон. В 1935-ом Бауманский райсовет постановил открыть в Богоявленском соборе большой кинотеатр, но решение вскоре отменили.

И еще несколько фактов из истории храма. В Богоявленском соборе покоятся мощи святителя Алексия, митрополита Московского, и погребены Святейший Патриарх Московский и всея Руси Сергий и Святейший Патриарх Московский и всея Руси Алексий II. В 1992 году Богоявленский собор стал кафедральным.

Святыни собора: Чудотворная Казанская икона Божией Матери, мощи святителя Алексия, митрополита Московского, икона Божией Матери «Всех скорбящих Радость», частицы мощей святителя Иоанна Златоуста, апостола Андрея Первозванного и святителя Московского Петра.

Народные традиции Крещения Господня

Каждый церковный праздник находит свое отражение в народных традициях. И чем богаче и древнее история народа, тем более сложные и интересные переплетения народного и церковного получаются. Многие обычаи далеки от истинного христианства и близки к язычеству, но они тем не менее интересны с исторической точки зрения — чтобы узнать народ лучше, чтобы суметь отделить суть того или иного Христова праздника от красочного потока народной фантазии.

На Руси Крещение было концом святок, девушки прекращали гадания — сугубо языческое занятие. Простой люд готовился к празднику, который, как считалось, очистит их от грехов, в том числе грехов святочных гаданий.

На Крещение совершали великое водосвятие. Причем два раза. Первый — в Крещенский сочельник. Воду освящали в купели, которая стояла в центре храма. Второй раз воду освящали уже в сам праздник Крещения — в любом местном водоеме: реке, озере, колодце. Во льду прорубали «иордань» — прорубь в виде креста или круга. Рядом ставили аналой и деревянный крест с ледяным голубком — символом Святого Духа.

В день Крещения после литургии люди шли к проруби крестным ходом. Священник служил молебен, три раза опускал в прорубь крест, испрашивая на воду Божие благословение. После этого все сельчане набирали из проруби святую воду и весело обливали ею друг друга. Некоторые удальцы даже купались в ледяной воде, чтобы, согласно народному поверью, очиститься от грехов. Следует отметить, что это поверье к учению Церкви не имеет никакого отношения. Купание в проруби (иордани) не является церковным таинством или обрядом, это именно народная традиция празднования Крещения Господня

Освящали не только сельские водоемы, но и реки в больших городах. Например, вот рассказ, как освящали воду в Москве на реке Неглинной 6 января 1699 года. В обряде принял участие сам император Петр I. А описал событие шведский посланник в Москве Густав Корб:

«Праздник Трех царей (волхвов), или, вернее, Богоявление Господне, ознаменован был благословением реки Неглинной. Процессия двигалась к реке в следующем порядке. Открывал шествие полк генерала де Гордона… Гордонов полк сменил другой, называемый Преображенским и обращавший на себя внимание новой зеленой одеждой. Место капитана занимал царь, внушавший высоким ростом почтение к своему Величеству. …На твердом льду реки была построена ограда (theatrum, иордань). Пятьсот духовных особ, иподьяконы, дьяконы, священники, архимандриты (abbates), епископы и архиепископы, облаченные в одеяния, подобающие их сану и должности и богато украшенные золотом, серебром, жемчугом и драгоценными камнями, придавали религиозной церемонии более величественный вид. Перед замечательным золотым крестом двенадцать клириков несли фонарь, в котором горели три свечи. Невероятное количество людей толпилось со всех сторон, улицы были полны, крыши были заняты людьми; зрители стояли и на городских стенах, тесно прижавшись друг к другу. Как только духовенство наполнило обширное пространство ограды, началась священная церемония, зажжено было множество свеч, и прежде всего воспоследовало призывание благодати Божией. После достодолжного призыва милости Божией, митрополит стал ходить с каждением кругом всей ограды, посередине которой лед проломан был пешнем в виде колодца, так что обнаружилась вода. После троекратного каждения ее митрополит освящал ее троекратным погружением горящей свечи и обычным благословением. …Затем патриарх, или в отсутствие его митрополит, выходя из ограды, кропит обычно его Царское Величество и всех солдат. Для конечного завершения праздничного торжества производили залп из орудий всех полков. …Перед началом этой церемонии на шести белых царских лошадях привозили покрытый красным сукном сосуд. В этом сосуде надлежало затем отвезти благословенную воду во дворец его Царского Величества. Точно также клирики отнесли некий сосуд для патриарха и очень много других для бояр и московских вельмож».

Святая Крещенская вода

Воду на Богоявление освящают два раза. Накануне, 18 января, в Крещенский сочельник — Чином Великого освящения воды, который еще называют «Великой агиасмой». И второй раз — в день Богоявления, 19 января, на Божественной литургии. Первая традиция восходит, скорее всего, к древнехристианской практике крещения оглашенных после утренней службы Богоявления. А вторая — связана с обычаем христиан Иерусалимской церкви шествовать в день Богоявления на Иордан к традиционному месту крещения Иисуса Христа.

По традиции, Крещенскую воду хранят год — до следующего праздника Крещения. Пьют ее натощак, благоговейно и с молитвой.

Когда набирать крещенскую воду?

Воду на Богоявление освящают два раза. Накануне, 18 января, в Крещенский сочельник — Чином Великого освящения воды, который еще называют «Великой агиасмой». И второй раз — в день Богоявления, 19 января, на Божественной литургии. Когда освящать воду, совершенно не важно.

Вся ли вода на Крещение святая?

Отвечает протоиерей Игорь Фомин, настоятель храма Александра Невского при МГИМО:

Помню, в детстве мы выходили из храма на Крещение и выносили с собой трехлитровый бидон крещенской воды, а потом, уже дома, разбавляли ее водой из-под крана. И весь год принимали воду как великую святыню — с благоговением.

В ночь на Крещение Господне, действительно, как говорит Предание, все водное естество освящается. И становится подобным водам Иордана, в которых был крещен Господь. Магия как раз была бы, если бы вода святой становилась только там, где ее батюшка освятил. Дух же Святой дышит, где хочет. И есть такое мнение, что в любой момент Крещения вода святая везде. А освящение воды — это видимый, торжественный церковный чин, который говорит нам о присутствии Бога здесь, на земле.

Крещенские морозы

Время праздника Богоявления на Руси обычно совпадало с крепкими морозами, поэтому их стали называть «крещенскими». Люди приговаривали: «Трещи мороз, не трещи, а минули Водокрещи».

Купание в проруби (иордани) на Крещение

На Руси простые люди называли Богоявление «Водокрещи» или «Иордань». Иордань — прорубь в форме креста или круга, прорубленная в любом водоеме и освященная в день Крещения Господня. После освящения удалые парни и мужики окунались и даже плавали в ледяной воде; считалось, что так можно смыть с себя грехи. Но это лишь народное суеверие. Церковь учит нас, что грехи смываются только покаянием через таинство Исповеди. А купание — это просто традиция. И тут, во-первых, важно понимать, что эта традиция совершенно необязательна для исполнения. Во-вторых, следует помнить о благоговейном отношении к святыне — крещенской воде. То есть, если мы все же решились на купание, то должны делать это разумно (учитывая состояние здоровья) и благоговейно — с молитвой. И, конечно, не заменяя купанием присутствие на праздничном богослужении в храме.

Крещенский сочельник

Празднику Богоявления предшествует Крещенский Сочельник, или Навечение Богоявления. Накануне праздника православные христиане соблюдают строгий пост. Традиционное блюдо этого дня — сочиво, которое готовят из крупы (например, пшеницы или риса), меда и изюма.

Сочиво

Для приготовления сочива вам понадобится:

— пшеница (зерно) – 200 г

— очищенные орехи – 30 г

— мак – 150 г

— изюм – 50 г

— фрукты или ягоды (яблоко, ежевика, малина и т.п.) или варенье – по вкусу

— ванильный сахар – по вкусу

— мед и сахар – по вкусу.

Пшеницу хорошо промыть, залить горячей водой, покрыв зерно, и варить в кастрюле на медленном огне до мягкости (или в глиняном горшочке, в духовке), периодически доливая горячую воду. Мак промыть, запарить горячей водой на 2-3 часа, слить воду, мак растереть, добавить по вкусу сахар, мед, ванильный сахар или любого варенья, покрошенных орехов, изюма, фрукты или ягоды по вкусу, добавить 1/2 стакана кипячёной воды, и всё это соединить с вареной пшеницей, выложить в керамическую миску и подать на стол в охлажденном состоянии.

Стихотворение о Крещении

Иван Бунин

Крещенская ночь

Темный ельник снегами, как мехом,

Опушили седые морозы,

В блестках инея, точно в алмазах,

Задремали, склонившись березы.

Неподвижно застыли их ветки,

А меж ними на снежное лоно,

Точно сквозь серебро кружевное,

Полный месяц глядит с небосклона.

Высоко он поднялся над лесом,

В ярком свете своем цепенея,

И причудливо стелются тени,

На снегу под ветвями чернея.

Замело чаши леса метелью, —

Только вьются следы и дорожки,

Убегая меж сосен и елок,

Меж березок до ветхой сторожки.

Убаюкала вьюга седая

Дикой песнею лес опустелый,

И заснул он, засыпанный вьюгой,

Весь сквозной, неподвижный и белый.

Спят таинственно стройные чащи,

Спят, одетые снегом глубоким,

И поляны, и луг, и овраги,

Где когда-то шумели потоки.

Тишина, – даже ветка не хрустнет!

А, быть может, за этим оврагом

Пробирается волк по сугробам

Осторожным и вкрадчивым шагом.

Тишина, – а, быть может, он близко…

И стою я, исполнен тревоги,

И гляжу напряженно на чащи,

На следы и кусты вдоль дороги.

В дальних чащах, где ветви как тени

В лунном свете узоры сплетают,

Все мне чудится что-то живое,

Все как будто зверьки пробегают.

Огонек из лесной караулки

Осторожно и робко мерцает,

Точно он притаился под лесом

И чего-то в тиши поджидает.

Бриллиантом лучистым и ярким,

То зеленым, то синим играя,

На востоке, у трона Господня,

Тихо блещет звезда, как живая.

А над лесом все выше и выше

Всходит месяц, – и в дивном покое

Замирает морозная полночь

И хрустальное царство лесное!

Митрополит Антоний Сурожский. Проповедь на Крещение Господне

19 января 1973 г.

Какие бывают животворящие и какие бывают страшные воды… В начале Книги Бытия мы читаем о том, как над водами носилось дыхание Божие и как из этих вод возникали все живые существа. В течение жизни всего человечества – но так ярко в Ветхом Завете – мы видим воды как образ жизни: они сохраняют жизнь жаждущего в пустыне, они оживотворяют поле и лес, они являются знаком жизни и милости Божией, и в священных книгах Ветхого и Нового Завета воды представляют собой образ очищения, омовения, обновления.

Но какие бывают страшные воды: воды Потопа, в которых погибли все, кто уже не мог устоять перед судом Божиим; и воды, которые мы видим в течение всей нашей жизни, страшные, губительные, темные воды наводнений…

И вот Христос пришел на Иорданские воды; в эти воды уже не безгрешной земли, а нашей земли, до самых недр своих оскверненной человеческим грехом и предательством. В эти воды приходили омываться люди, кающиеся по проповеди Иоанна Предтечи; как тяжелы были эти воды грехом людей, которые ими омывались! Если бы мы только могли видеть, как омывающие эти воды постепенно тяжелели и становились страшными этим грехом! И в эти воды пришел Христос окунуться в начале Своего подвига проповеди и постепенного восхождения на Крест, погрузиться в эти воды, носящие всю тяжесть человеческого греха – Он, безгрешный.

Этот момент Крещения Господня – один из самых страшных и трагических моментов Его жизни. Рождество – это мгновение, когда Бог, по Своей любви к человеку желающий спасти нас от вечной погибели, облекается в человеческую плоть, когда плоть человеческая пронизывается Божеством, когда обновляется она, делается вечной, чистой, светозарной, той плотью, которая путем Креста, Воскресения, Вознесения сядет одесную Бога и Отца. Но в день Крещения Господня завершается этот подготовительный путь: теперь, созревший уже в Своем человечестве Господь, достигший полной меры Своей зрелости Человек Иисус Христос, соединившийся совершенной любовью и совершенным послушанием с волей Отца, идет вольной волей, свободно исполнить то, что Предвечный Совет предначертал. Теперь Человек Иисус Христос эту плоть приносит в жертву и в дар не только Богу, но всему человечеству, берет на Свои плечи весь ужас человеческого греха, человеческого падения, и окунается в эти воды, которые являются теперь водами смерти, образом погибели, несут в себе все зло, весь яд и всю смерть греховную.

Крещение Господне , в дальнейшем развитии событий, ближе всего походит на ужас Гефсиманского сада, на отлученность крестной смерти и на сошествие во ад. Тут тоже Христос так соединяется с судьбой человеческой, что весь ее ужас ложится на Него, и сошествие во ад является последней мерой Его единства с нами, потерей всего – и победой над злом.

Вот почему так трагичен этот величественный праздник, и вот почему воды иорданские, носящие всю тяжесть и весь ужас греха, прикосновением к телу Христову, телу безгрешному, всечистому, бессмертному, пронизанному и сияющему Божеством, телу Богочеловека, очищаются до глубин и вновь делаются первичными, первобытными водами жизни, способными очищать и омывать грех, обновлять человека, возвращать ему нетление, приобщать его Кресту, делать его чадом уже не плоти, а вечной жизни, Царства Божия.

Как трепетен этот праздник! Вот почему, когда мы освящаем воды в этот день, мы с таким изумлением и благоговением на них глядим: эти воды сошествием Святого Духа делаются водами Иорданскими, не только первобытными водами жизни, но водами, способными дать жизнь не временную только, но и вечную; вот почему мы приобщаемся этим водам благоговейно, трепетно; вот почему Церковь называет их великой святыней и призывает нас иметь их в домах на случай болезни, на случай душевной скорби, на случай греха, для очищения и обновления, для приобщения к новизне очищенной жизни. Будем вкушать эти воды, будем прикасаться к ним благоговейно. Началось через эти воды обновление природы, освящение твари, преображение мира. Так же как в Святых Дарах, и тут мы видим начало будущего века, победу Божию и начало вечной жизни, вечной славы – не только человека, но всей природы, когда Бог станет всем во всем.

Слава Богу за Его бесконечную милость, за Его Божественное снисхождение, за подвиг Сына Божия, ставшего Сыном человеческим! Слава Богу, что Он обновляет и человека и судьбы наши, и мир, в котором мы живем, и что жить-то мы все-таки можем надеждой уже одержанной победы и ликованием о том, что мы ждем дня Господня , великого, дивного, страшного, когда воссияет весь мир благодатью принятого, а не только данного Духа Святого! Аминь.

Митрополит Антоний Сурожский. Проповедь на Крещение Господне

19 января 1979 г.

С каким чувством благоговения ко Христу и благодарности к родным, которые нас приводят к вере, мы вспоминаем о своем Крещении : как дивно думать, что поскольку наши родители или близкие нам люди открыли веру во Христа, поручились за нас перед Церковью и перед Богом, мы, Таинством Крещения , стали Христовы, мы названы Его именем. Мы это имя носим с таким же благоговением и изумлением, как юная невеста несет имя человека, которого она полюбила на жизнь и на смерть и который дал ей свое имя; как это человеческое имя мы бережем! Как оно нам дорого, как оно нам свято, как нам страшно было бы поступком, образом своим его отдать на хулу недоброжелателям… И именно так соединяемся мы со Христом, Спаситель Христос, Бог наш, ставший Человеком, нам дает носить Свое имя. И как на земле по нашим поступкам судят о всем роде, который носит то же имя, так и тут по нашим поступкам, по нашей жизни судят о Христе.

Какая же это ответственность! Апостол Павел почти две тысячи лет тому назад предупреждал молодую христианскую Церковь, что ради тех из них, которые живут недостойно своего призвания, хулится имя Христово. Разве не так теперь? Разве во всем мире сейчас миллионы людей, которые хотели бы найти смысл жизни, радость, глубину в Боге, не отстраняются от Него, глядя на нас, видя, что мы не являемся, увы, живым образом евангельской жизни – ни лично, ни как общество?

И вот в день Крещения Господня хочется перед Богом сказать от себя и призвать всех сказать, кому было дано креститься во имя Христа: вспомните, что вы стали теперь носителями этого святого и божественного имени, что по вас будут судить Бога, Спасителя вашего, Спасителя всех, что если ваша жизнь – моя жизнь! – будет достойна этого дара Божия, то тысячи вокруг спасутся, а если будет недостойна – пропадут: без веры, без надежды, без радости и без смысла. Христос пришел на Иордан безгрешным, погрузился в эти страшные иорданские воды, которые как бы отяжелели, омывая грех человеческий, образно стали как бы мертвыми водами – Он в них погрузился и приобщился нашей смертности и всем последствиям человеческого падения, греха, унижения для того, чтобы нас сделать способными жить достойно человеческого нашего призвания, достойно Самого Бога, Который нас призвал быть родными Ему, детьми, быть Ему родными и своими…

Отзовемся же на это дело Божие, на этот Божий призыв! Поймем, как высоко, как величественно наше достоинство, как велика наша ответственность, и вступим в теперь уже начавшийся год так, чтобы быть славой Божией и спасением каждого человека, который прикоснется нашей жизни! Аминь.

Святитель Феофан Затворник. Мысли на каждый день года — Крещение Господне

Богоявление (Тит 2, 11-14; З, 4-7; Мф З, 13-17). Крещение Господа названо Богоявлением потому что в нем явил Себя так осязательно единый истинный Бог в Троице покланяемый: Бог Отец — гласом с неба, Бог Сын — воплотившийся — крещением. Бог Дух Святый — нисшествием на Крещаемого. Тут явлено и таинство отношения лиц Пресвятой Троицы. Бог Дух Святый от Отца исходит и в Сыне почивает а не исходит от Него. Явлено здесь и то, что воплощенное домостроительство спасения совершено Богом Сыном воплотившимся, соприсущу Ему Духу Святому и Богу Отцу. Явлено и то, что и спасение каждого может совершиться не иначе, как в Господе Иисусе Христе, благодатью Св. Духа, по благоволению Отца. Все таинства христианские сияют здесь божественным светом своим и просвещают умы и сердца с верою совершающих это великое празднество. Приидите, востечем умно горе, и погрузимся в созерцание этих таин спасения нашего, поя: во Иордане крещающуся Тебе, Господи, Тройческое явися поклонение, — спасение тройчески нам устрояющее и нас тройчески спасающее.

Загрузка…

This article is about the Christian feast day. For other uses, see Epiphany.

| Epiphany | |

|---|---|

The Adoration of the Magi by Edward Burne-Jones (1904) |

|

| Also called | Baptism of Jesus, Three Kings Day, Denha, Little Christmas, Theophany, Timkat, Reyes |

| Observed by | Christians |

| Type | Church service, winter swimming, chalking the door, house blessings, star singing |

| Significance |

|

| Date |

|

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to |

|

Epiphany ( ə-PIF-ə-nee), (also known as Theophany in Eastern Christian tradition[1]) is a Christian feast day commemorating the visit of the Magi, the baptism of Christ, and the Miracle at Cana.[2]

In Western Christianity, the feast commemorates principally (but not solely) the visit of the Magi to the Christ Child, and thus Jesus Christ’s physical manifestation to the Gentiles.[3][4] It is sometimes called Three Kings’ Day, and in some traditions celebrated as Little Christmas.[5] Moreover, the feast of the Epiphany, in some denominations, also initiates the liturgical season of Epiphanytide.[6][7]

Eastern Christians, on the other hand, commemorate the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River, seen as his manifestation to the world as the Son of God.[2] The spot marked by Al-Maghtas in Jordan, adjacent to Qasr al-Yahud in the West Bank, is considered to be the original site of the baptism of Jesus and the ministry of John the Baptist.[8][9]

The traditional date for the feast is January 6. However, since 1970, the celebration is held in some countries on the Sunday after January 1. Those Eastern Churches which are still following the Julian calendar observe the feast on what, according to the internationally used Gregorian calendar, is January 19,[10] because of the current 13-day difference between the Julian and Gregorian calendars.[11]

In many Western Churches, the eve of the feast is celebrated as Twelfth Night (Epiphany Eve).[12][13] The Monday after Epiphany is known as Plough Monday.[14]

Popular Epiphany customs include Epiphany singing, chalking the door, having one’s house blessed, consuming Three Kings Cake, winter swimming, as well as attending church services.[15] It is customary for Christians in many localities to remove their Christmas decorations on Epiphany Eve (Twelfth Night),[16] although those in other Christian countries historically remove them on Candlemas, the conclusion of Epiphanytide.[17][18] According to the first tradition, those who fail to remember to remove their Christmas decorations on Epiphany Eve must leave them untouched until Candlemas, the second opportunity to remove them; failure to observe this custom is considered inauspicious.[19][20]

Etymology and original word usage[edit]

The word Epiphany is from Koine Greek ἐπιφάνεια, epipháneia, meaning manifestation or appearance. It is derived from the verb φαίνειν, phainein, meaning «to appear».[21] In classical Greek it was used for the appearance of dawn, of an enemy in war, but especially of a manifestation of a deity to a worshiper (a theophany). In the Septuagint the word is used of a manifestation of the God of Israel (2 Maccabees 15:27).[22] In the New Testament the word is used in 2 Timothy 1:10 to refer either to the birth of Christ or to his appearance after his resurrection, and five times to refer to his Second Coming.[22]

Alternative names for the feast in Greek include τα Θεοφάνεια, ta Theopháneia «Theophany» (a neuter plural rather than feminine singular), η Ημέρα των Φώτων, i Iméra ton Fóton (modern Greek pronunciation), «The Day of the Lights», and τα Φώτα, ta Fóta, «The Lights».[23]

History[edit]

Epiphany may have originated in the Greek-speaking eastern half of the Roman Empire as a feast to honor the baptism of Jesus. Around 200, Clement of Alexandria wrote that, «But the followers of [the early Christian Gnostic religious teacher] Basilides celebrate the day of His Baptism too, spending the previous night in readings. And they say that it was the 15th of the month Tybi of the 15th year of Tiberius Caesar. And some say that it was observed the 11th of the same month.» The Egyptian dates given correspond to January 6 and 10.[24] The Basilides were a Gnostic sect.

The reference to «readings» suggests that the Basilides were reading the Gospels. In ancient gospel manuscripts, the text is arranged to indicate passages for liturgical readings. If a congregation began reading Mark at the beginning of the year, it might arrive at the story of the Baptism on January 6, thus explaining the date of the feast.[25][26] If Christians read Mark in the same format the Basilides did, the two groups could have arrived at the January 6 date independently.[27]

The earliest reference to Epiphany as a Christian feast was in A.D. 361, by Ammianus Marcellinus.[28] The holiday is listed twice, which suggests a double feast of baptism and birth.[24] The baptism of Jesus was originally assigned to the same date as the birth because Luke 3:23 was misread to mean that Jesus was exactly 30 when he was baptized.

Epiphanius of Salamis says that January 6 is Christ’s «Birthday; that is, His Epiphany» (hemera genethlion toutestin epiphanion).[29] He also asserts that the Miracle at Cana occurred on the same calendar day.[30] Epiphanius assigns the Baptism to November 6.[24]

The scope to Epiphany expanded to include the commemoration of his birth; the visit of the magi, all of Jesus’ childhood events, up to and including the Baptism by John the Baptist; and even the miracle at the wedding at Cana in Galilee.[31]

In the Latin-speaking West, the holiday emphasized the visit of the magi. The magi represented the non-Jewish peoples of the world, so this was considered a «revelation to the gentiles.»[32] In this event, Christian writers also inferred a revelation to the Children of Israel. John Chrysostom identified the significance of the meeting between the magi and Herod’s court: «The star had been hidden from them so that, on finding themselves without their guide, they would have no alternative but to consult the Jews. In this way the birth of Jesus would be made known to all.»[33]

In 385, the pilgrim Egeria (also known as Silvia) described a celebration in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, which she called «Epiphany» that commemorated the Nativity.[34] Even at this early date, there was an octave associated with the feast.

In a sermon delivered on December 25, 380, St. Gregory of Nazianzus referred to the day as «the Theophany» (ta theophania, formerly the name of a pagan festival at Delphi),[35] saying expressly that it is a day commemorating «the holy nativity of Christ» and told his listeners that they would soon be celebrating the baptism of Christ.[36] Then, on January 6 and 7, he preached two more sermons,[37] in which he declared that the celebration of the birth of Christ and the visitation of the Magi had already taken place, and that they would now commemorate his Baptism.[38] At this time, celebration of the two events was beginning to be observed on separate occasions, at least in Cappadocia.

Saint John Cassian says that even in his time (beginning of the 5th century), Egyptian monasteries celebrated the Nativity and the Baptism together on January 6.[39] The Armenian Apostolic Church continues to celebrate January 6 as the only commemoration of the Nativity.

Music[edit]

Classical[edit]

Johann Sebastian Bach composed in Leipzig two cantatas for the feast which concluded Christmastide:

- Sie werden aus Saba alle kommen, BWV 65, (1724)[40]

- Liebster Immanuel, Herzog der Frommen, BWV 123, (1725)[41]

Part VI of his Christmas Oratorio, Herr, wenn die stolzen Feinde schnauben, was also designated to be performed during the service for Epiphany.[42]

In Ottorino Respighi’s symphonic tone poem Roman Festivals, the final movement is subtitled «Bofana» and takes place during Epiphany.

Carols and hymns[edit]

«Nun liebe Seel, nun ist es Zeit» is a German Epiphany hymn by Georg Weissel, first printed in 1642.

Two very familiar Christmas carols are associated with the Epiphany holiday: «As with gladness, men of old», written by William Chatterton Dix in 1860 as a response to the many legends which had grown up surrounding the Magi;[43][44] and «We Three Kings of Orient Are», written by the Reverend John Henry Hopkins Jr. – then an ordained deacon in the Episcopal Church[45] – who was instrumental in organizing an elaborate holiday pageant (which featured this hymn) for the students of the General Theological Seminary in New York City in 1857 while serving as the seminary’s music director.

Another popular hymn, less known culturally as a carol, is «Songs of thankfulness and praise», with words written by Christopher Wordsworth and commonly sung to the tune «St. Edmund» by Charles Steggall.

A carol used as an anthem for the Epiphany holiday is «The Three Kings».

Date of the celebration[edit]

Holy (Epiphany) water vessel from 15th–16th centuries. It is found on Hisar near the town of Leskovac, Serbia. Photographed in National museum of Leskovac.

Until 1955, when Pope Pius XII abolished all but three liturgical octaves, the Latin Church celebrated Epiphany as an eight-day feast, known as the Octave of Epiphany, beginning on January 6 and ending on January 13. The Sunday within that octave had been since 1893 the feast of the Holy Family, and Christmastide was reckoned as the twelve days ending on January 5, followed by the January 6–13 octave. The 1969 revision of the General Roman Calendar made the date variable to some extent, stating: «The Epiphany of the Lord is celebrated on 6 January, unless, where it is not observed as a holy day of obligation, it has been assigned to the Sunday occurring between 2 and 8 January.»[46] It also made the Feast of the Epiphany part of Christmas Time, which it defined as extending from the First Vespers of Christmas (the evening of December 24) up to and including the Sunday after Epiphany (the Sunday after January 6).[47]

Lutheran, Anglican, Methodist and United Protestant congregations, along with those of other denominations, may celebrate Epiphany on January 6, on the following Sunday within the Epiphany week (octave), or at another time (Epiphany Eve January 5, the nearest Sunday, etc.) as local custom dictates.[48][49] Prior to 1976, Anglican churches observed an eight-day octave, beginning on January 6. Today, The Epiphany of our Lord,[50] classified as a Principal Feast, is observed in some Anglican provinces on January 6 exclusively (e.g., the Anglican Church of Canada)[50] but in the Church of England the celebration is «on 6 January or transferred to the Sunday falling between 2 and 8 January».[51]

Eastern churches celebrate Epiphany (Theophany) on January 6. Some, as in Greece, employ the modern Revised Julian calendar, which until 2800 coincides with the Gregorian calendar, the one in use for civil purposes in most countries. Other Eastern churches, as in Russia, hold to the older Julian calendar for reckoning church dates. In these old-calendar churches Epiphany falls at present on Gregorian January 19 – which is January 6 in the Julian calendar.

The Indian Orthodox Church celebrates the feast of Epiphany, Denaha [Syriac term which means rising] on January 6, and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church celebrates on January 19 as the Timkath festival, which was included in the UNESCO heritage list of festivals.

Epiphany season[edit]

In some Churches, the feast of the Epiphany initiates the Epiphany season, also known as Epiphanytide.

In Advent 2000, the Church of England, Mother Church of the Anglican Communion, introduced into its liturgy an optional Epiphany season by approving the Common Worship series of services as an alternative to those in the Book of Common Prayer, which remains the Church’s normative liturgy and in which no such liturgical season appears. An official publication of the Church of England states: «The Christmas season is often celebrated for twelve days, ending with the Epiphany. Contemporary use has sought to express an alternative tradition, in which Christmas lasts for a full forty days, ending with the Feast of the Presentation on 2 February.»[52] It presents the latter part of this period as the Epiphany season, comprising the Sundays of Epiphany and ending «only with the Feast of the Presentation (Candlemas)».[53]

Another interpretation of «Epiphany season» applies the term to the period from Epiphany to the day before Ash Wednesday. Some Methodists in the United States and Singapore follow these liturgies.[6][54] Lutherans celebrate the last Sunday before Ash Wednesday as the Transfiguration of our Lord, and it has been said that they call the whole period from Epiphany to then as Epiphany season.[55] The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America used the terms «Time after Epiphany» to refer to this period.[56] The expression with «after» has been interpreted as making the period in question correspond to that of Ordinary Time.[57][58]

The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) does not celebrate Epiphany or Pentecost as seasons; for this Church, expressions such as «Fifth Sunday after Epiphany» indicate the passing of time, rather than a liturgical season. It instead uses the term «Ordinary Time».[59]

In the Catholic Church, «Christmas Time runs from First Vespers (Evening Prayer I) of the Nativity of the Lord up to and including the Sunday after Epiphany or after 6 January»;[47] and «Ordinary Time begins on the Monday which follows the Sunday occurring after 6 January».[60] Before the 1969 revision of its liturgy, the Sundays following the Octave of Epiphany or, when this was abolished, following the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord, which was instituted to take the place of the Octave Day of Epiphany were named as the «Second (etc., up to Sixth) Sunday after Epiphany», as the at least 24 Sundays following Pentecost Sunday and Trinity Sunday were known as the «Second (etc.) Sunday after Pentecost». (If a year had more than 24 Sundays after Pentecost, up to four unused post-Epiphany Sundays were inserted between the 23rd and the 24th Sunday after Pentecost.) The Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices, which has received the imprimatur of John Michael D’Arcy, with reference to Epiphanytide, thus states that «The Epiphany season extends from January 6 to Septuagesima Sunday, and has from one to six Sundays, according to the date of Easter. White is the color for the octave; green is the liturgical color for the season.»[61]

Epiphany in different Christian traditions[edit]

Epiphany is celebrated by both the Eastern and Western Churches, but a major difference between them is precisely which events the feast commemorates. For Western Christians, the feast primarily commemorates the coming of the Magi, with only a minor reference to the baptism of Jesus and the miracle at the Wedding at Cana. Eastern churches celebrate the Baptism of Christ in the Jordan. In both traditions, the essence of the feast is the same: the manifestation of Christ to the world (whether as an infant or in the Jordan), and the Mystery of the Incarnation. The miracle at the Wedding at Cana is also celebrated during Epiphany as a first manifestation of Christ’s public life.[62]

Western churches[edit]

K † M † B † 2009 written on a door of a rectory in a Czech village, to bless the house by Christ

Even before 354,[63] the Western Church had separated the celebration of the Nativity of Christ as the feast of Christmas and set its date as December 25; it reserved January 6 as a commemoration of the manifestation of Christ, especially to the Magi, but also at his baptism and at the wedding feast of Cana.[64] In 1955 a separate feast of the Baptism of the Lord was instituted, thus weakening further the connection in the West between the feast of the Epiphany and the commemoration of the baptism of Christ. However, Hungarians, in an apparent reference to baptism, refer to the January 6 celebration as Vízkereszt, a term that recalls the words «víz» (water) and «kereszt, kereszt-ség» (baptism).

Liturgical practice in Western churches[edit]

Many in the West, such as adherents of the Anglican Communion, Lutheran Churches and Methodist Churches, observe a twelve-day festival, starting on December 25, and ending on January 5, known as Christmastide or The Twelve Days of Christmas.

The Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year and the General Roman Calendar of the Roman Catholic Church determine since 1969 that «Christmas Time runs from First Vespers (Evening Prayer I) of the Nativity of the Lord up to and including the Sunday after Epiphany or after January 6».[47] Some regions and especially some communities celebrating the Tridentine Mass extend the season to as many as forty days, ending Christmastide traditionally on Candlemas (February 2).

On the Feast of the Epiphany in some parts of central Europe the priest, wearing white vestments, blesses Epiphany water, frankincense, gold, and chalk. The chalk is used to write the initials of the three magi (traditionally, Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar), over the doors of churches and homes. The initials may also be interpreted as the Latin phrase, Christus mansionem benedicat (may Christ bless the house).

According to ancient custom, the priest announced the date of Easter on the feast of Epiphany. This tradition dated from a time when calendars were not readily available, and the church needed to publicize the date of Easter, since many celebrations of the liturgical year depend on it.[65] The proclamation may be sung or proclaimed at the ambo by a deacon, cantor, or reader either after the reading of the Gospel or after the postcommunion prayer.[65]

The Roman Missal thus provides a formula with appropriate chant (in the tone of the Exsultet) for proclaiming on Epiphany, wherever it is customary to do so, the dates in the calendar for the celebration of Ash Wednesday, Easter Sunday, Ascension of Jesus Christ, Pentecost, the Body and Blood of Christ, and the First Sunday of Advent that will mark the following liturgical year.[66]

Some western rite churches, such as the Anglican and Lutheran churches, will follow practises similar to the Catholic Church. Church cantatas for the Feast of Epiphany were written by Protestant composers such as Georg Philipp Telemann, Christoph Graupner, Johann Sebastian Bach and Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel.[67][68][69][70]

Eastern Orthodox churches[edit]

The name of the feast as celebrated in the Orthodox churches may be rendered in English as the Theophany, as closer in form to the Greek Θεοφάνεια («God shining forth» or «divine manifestation»). Here it is one of the Great Feasts of the liturgical year, being third in rank, behind only Paskha (Easter) and Pentecost in importance. It is celebrated on January 6 of the calendar that a particular Church uses. On the Julian calendar, which some of the Orthodox churches follow, that date corresponds, during the present century, to January 19 on the Gregorian or Revised Julian calendar. The earliest reference to the feast in the Eastern Church is a remark by St. Clement of Alexandria in Stromateis, I, xxi, 45:

And there are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord’s birth, but also the day… And the followers of Basilides hold the day of his baptism as a festival, spending the night before in readings. And they say that it was the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar, the fifteenth day of the month of Tubi; and some that it was the eleventh of the same month.

(11 and 15 of Tubi are January 6 and 10, respectively.)

If this is a reference to a celebration of Christ’s birth, as well as of his baptism, on January 6, it corresponds to what continues to be the custom of the Armenian Apostolic Church, which celebrates the birth of Jesus on January 6 of the calendar used, calling the feast that of the Nativity and Theophany of Our Lord.[71][72]

Origen’s list of festivals (in Contra Celsum, VIII, xxii) omits any reference to Epiphany. The first reference to an ecclesiastical feast of the Epiphany, in Ammianus Marcellinus (XXI:ii), is in 361.

In parts of the Eastern Church, January 6 continued for some time as a composite feast that included the Nativity of Jesus: though Constantinople adopted December 25 to commemorate Jesus’ birth in the fourth century, in other parts the Nativity of Jesus continued to be celebrated on January 6, a date later devoted exclusively to commemorating his Baptism.[63]

Today in Eastern Orthodox churches, the emphasis at this feast is on the shining forth and revelation of Jesus Christ as the Messiah and Second Person of the Trinity at the time of his baptism. It is also celebrated because, according to tradition, the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River by St. John the Baptist marked one of only two occasions when all three Persons of the Trinity manifested themselves simultaneously to humanity: God the Father by speaking through the clouds, God the Son being baptized in the river, and God the Holy Spirit in the shape of a dove descending from heaven (the other occasion was the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor). Thus the holy day is considered to be a Trinitarian feast.

The Orthodox consider Jesus’ Baptism to be the first step towards the Crucifixion, and there are some parallels in the hymnography used on this day and the hymns chanted on Good Friday.

Liturgical practice in Eastern churches[edit]

Forefeast: The liturgical Forefeast of Theophany begins on January 2[73] and concludes with the Paramony on January 5.

Paramony: The Eve of the Feast is called Paramony (Greek: παραμονή, Slavonic: navechérie). Paramony is observed as a strict fast day, on which those faithful who are physically able, refrain from food until the first star is observed in the evening, when a meal with wine and oil may be taken. On this day the Royal Hours are celebrated, thus tying together this feast with Nativity and Good Friday. The Royal Hours are followed by the Divine Liturgy of St. Basil which combines Vespers with the Divine Liturgy. During the Vespers, fifteen Old Testament lections which foreshadow the Baptism of Christ are read, and special antiphons are chanted. If the Feast of the Theophany falls on a Sunday or Monday, the Royal Hours are chanted on the previous Friday, and on the Paramony the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom is celebrated in the morning. The fasting is lessened to some degree in this case.

Theophany Crucession in Bulgaria. The priests are going to throw a wooden cross in the Yantra river. Believers will then jump into the icy waters to recover the cross.

Blessing of Waters: The Orthodox Churches perform the Great Blessing of Waters on Theophany.[74] The blessing is normally done twice: once on the Eve of the Feast—usually at a Baptismal font inside the church—and then again on the day of the feast, outdoors at a body of water. Following the Divine Liturgy, the clergy and people go in a Crucession (procession with the cross) to the nearest body of water, be it a beach, harbor, quay, river, lake, swimming pool, water depot, etc. (ideally, it should be a body of «living water»). At the end of the ceremony the priest will bless the waters. In the Greek practice, he does this by casting a cross into the water. If swimming is feasible on the spot, any number of volunteers may try to recover the cross. The person who gets the cross first swims back and returns it to the priest, who then delivers a special blessing to the swimmer and their household. Certain such ceremonies have achieved particular prominence, such as the one held annually at Tarpon Springs, Florida. In Russia, where the winters are severe, a hole will be cut into the ice so that the waters may be blessed. In such conditions, the cross is not cast into the water, but is held securely by the priest and dipped three times into the water.

The water that is blessed on this day is sometimes known as «Theophany Water», though usually just «holy water», and is taken home by the faithful, and used with prayer as a blessing. People will not only bless themselves and their homes by sprinkling with holy water, but will also drink it. The Orthodox Church teaches that holy water differs from ordinary water by virtue of the incorruptibility bestowed upon it by a blessing that transforms its very nature.[75] a miracle attested to as early as St. John Chrysostom.[76]

Theophany is a traditional day for performing Baptisms, and this is reflected in the Divine Liturgy by singing the baptismal hymn, «As many as have been baptized into Christ, have put on Christ. Alleluia,» in place of the Trisagion.

House Blessings: On Theophany the priest will begin making the round of the parishioner’s homes to bless them. He will perform a short prayer service in each home, and then go through the entire house, gardens and outside-buildings, blessing them with the newly blessed Theophany Water, while all sing the Troparion and Kontakion of the feast. This is normally done on Theophany, or at least during the Afterfeast, but if the parishioners are numerous, and especially if many live far away from the church, it may take some time to bless each house. Traditionally, these blessings should all be finished before the beginning of Great Lent.

Afterfeast: The Feast of Theophany is followed by an eight-day Afterfeast on which the normal fasting laws are suspended. The Saturday and Sunday after Theophany have special readings assigned to them, which relate to the Temptation of Christ and to penance and perseverance in the Christian struggle. There is thus a liturgical continuum between the Feast of Theophany and the beginning of Great Lent.

Oriental Orthodox[edit]

In the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the feast is known as Timkat and is celebrated on the day that the Gregorian calendar calls January 19, but on January 20 in years when Enkutatash in the Ethiopian calendar falls on Gregorian September 12 (i.e. when the following February in the Gregorian calendar will have 29 days). The celebration of this feast features blessing of water and solemn processions with the sacred tabot. A priest carries this to a body of water where it stays overnight, with the Metsehafe Qeddassie celebrated in the early morning. Later in the morning, the water is blessed to the accompaniment of the reading of the four Gospel accounts of the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan and the people are sprinkled with or go into the water. The tabot returns in procession to the church.

Among the Syriac Christians the feast is called denho (up-going), a name to be connected with the notion of rising light expressed in Luke 1:78. In the East Syriac rite, the season of Epiphany (Epiphanytide) is known as Denha.

In the Armenian Apostolic Church, January 6 is celebrated as the Nativity (Soorp Tsnund) and Theophany of Christ. The feast is preceded by a seven-day fast. On the eve of the feast, the Divine Liturgy is celebrated. This liturgy is referred to as the Chragaluytsi Patarag (the Eucharist of the lighting of the lamps) in honor of the manifestation of Jesus as the Son of God. Both the Armenian Apostolic Church’s and Assyrian Church of the East’s liturgy is followed by a blessing of water, during which the cross is immersed in the water, symbolizing Jesus’ descent into the Jordan, and holy myron (chrism) is poured in, symbolic of the descent of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus. The next morning, after the Liturgy, the cross is removed from the vessel of holy water and all come forward to kiss the cross and partake of the blessed water.

National and local customs[edit]

A traditional Bulgarian all-male horo dance in ice-cold water on Theophany

Epiphany is celebrated with a wide array of customs around the world. In some cultures, the greenery and nativity scenes put up at Christmas are taken down at Epiphany. In other cultures these remain up until Candlemas on February 2. In countries historically shaped by Western Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Protestantism) these customs often involve gift giving, «king cakes» and a celebratory close to the Christmas season. In traditionally Orthodox nations, water, baptismal rites and house blessings are typically central to these celebrations.

Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay[edit]

In Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay, as in other Latin American countries, the day is called «Día de Reyes» (The Day of Kings, a reference to the Biblical Magi), commemorating the arrival of the Magi to revere Jesus as son of God. The night of January 5 into the morning of January 6 is known as «Noche de Reyes» (The Night of Kings) and children leave their shoes by the door, along with grass and water for the camels. On the morning of January 6, they get up early and rush to see their shoes, where they are expecting to find gifts left by the «Reyes» who, according to tradition, bypass the houses of children who are awake. On January 6, a «Rosca de Reyes» (a ring-shaped Epiphany cake) is eaten and all Christmas decorations are traditionally put away.

Bulgaria[edit]

In Bulgaria, Epiphany is celebrated on January 6 and is known as Bogoyavlenie («Manifestation of God»), Кръщение Господне (Krashtenie Gospodne or «Baptism of the Lord») or Yordanovden («Day of Jordan», referring to the river). On this day, a wooden cross is thrown by a priest into the sea, river or lake and young men race to retrieve it. As the date is in early January and the waters are close to freezing, this is considered an honorable act and it is said that good health will be bestowed upon the home of the swimmer who is the first to reach the cross.[77]

In the town of Kalofer, a traditional horo with drums and bagpipes is played in the icy waters of the Tundzha river before the throwing of the cross.[78][79]

Benelux[edit]

Children in Flanders celebrating Driekoningen

The Dutch and Flemish call this day Driekoningen, while German speakers call it Dreikönigstag (Three Kings’ Day). In the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and neighboring Germany, children in groups of three (symbolizing the Biblical Magi) proceed in costume from house to house while singing songs typical for the occasion, and receiving a coin or some sweets at each door. They may each carry a paper lantern symbolizing the star.[80] In some places, especially Holland, these troupes gather for competitions and present their skits/songs for an audience. As in Belgium, Koningentaart (Kings’ tart), puff pastry with almond filling, is prepared with a black bean hidden inside. Whoever finds the bean in his or her piece is king or queen for the day. A more typically Dutch version is Koningenbrood, or Kings’ bread. In the Netherlands, the traditions have died out, except for very few places.[81] Another Low Countries tradition on Epiphany is to open up doors and windows to let good luck in for the coming year.

Brazil[edit]

In Brazil, the day is called «Dia dos Reis» (The Day of Kings) and in the rest of Latin America «Día de Reyes» commemorating the arrival of the Magi to confirm Jesus as son of God. The night of January 5 into the morning of January 6 is known as «Night of Kings» (also called the Twelfth Night) and is feasted with music, sweets and regional dishes as the last night of Nativity, when Christmas decorations are traditionally put away.[82]

Chile[edit]

This day is sometimes known as the Día de los Tres Reyes Magos (The day of the Three Royal Magi) or La Pascua de los Negros (Holy Day of the Black men)[83] in Chile, although the latter is rarely heard, because it was the day when slaves were allowed not to work.

Dominican Republic[edit]

In the Dominican Republic, the Día de los Tres Reyes Magos (The day of the Three Royal Magi) and in this day children receive gifts on the christmas tree in a similar fashion to Christmas day. On this day public areas are very active with children accompanied by their parents trying out their new toys.

A common practice is to leave toys under the children’s beds on January 5, so when they wake up on January 6, they are made to believe the gifts and toys were left from Santa Claus or the Three Kings. however, and particularly in the larger cities and in the North, local traditions are now being observed and intertwined with the greater North American Santa Claus tradition, as well as with other holidays such as Halloween, due to Americanization via film and television, creating an economy of gifting tradition that spans from Christmas Day until January 6.

Egypt[edit]

The feast of the Epiphany is celebrated by the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, which falls on 11 Tobe of the Coptic calendar, as the moment when in the baptism of Jesus the skies opened and God himself revealed to all as father of Jesus and all mankind. It is then a moment of revelation of epiphany. This celebration started to include all the processes of incarnation of Jesus, from his birth on Christmas until his baptism in the river Jordan. For the Coptic Orthodox Church it is also a moment in which the path of Jesus to the Cross begins. Therefore, in many celebrations there are certain similarities with the celebrations of Holy Friday during the time of Easter. Since the Epiphany is one of the seven great feasts of the Coptic Orthodox Church, it is a day of strict fasting, and several religious celebrations are held on this day. The day is related to the blessing of waters that are used all throughout the year in the church celebrations, and it is a privileged day to celebrate baptisms. It is also a day in which many houses are blessed with water. It may take several days for the local priest to bless all the houses of the parishioners that ask for it, and so the blessing of the houses may go into the after-feasts of the Epiphany celebrations. However, it must be done before the beginning of Lent.[84]

England[edit]

In England, the celebration of the night before Epiphany, Epiphany Eve, is known as Twelfth Night (the first night of Christmas is December 25–26, and Twelfth Night is January 5–6), and was a traditional time for mumming and the wassail. The Yule log was left burning until this day, and the charcoal left was kept until the next Christmas to kindle next year’s Yule log, as well as to protect the house from fire and lightning.[85] In the past, Epiphany was also a day for playing practical jokes, similar to April Fool’s Day. Today in England, Twelfth Night is still as popular a day for plays as when Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night was first performed in 1601, and annual celebrations involving the Holly Man are held in London.[86] A traditional dish for Epiphany was Twelfth Cake, a rich, dense, typically English fruitcake. As in Europe, whoever found the baked-in bean was king for a day, but uniquely to English tradition other items were sometimes included in the cake. Whoever found the clove was the villain, the twig, the fool, and the rag, the tart.[clarification needed] Anything spicy or hot, like ginger snaps and spiced ale, was considered proper Twelfth Night fare, recalling the costly spices brought by the Wise Men. Another English Epiphany sweetmeat was the traditional jam tart, made appropriate to the occasion by being fashioned in the form of a six-pointed star symbolising the Star of Bethlehem, and thus called Epiphany tart. The discerning English cook sometimes tried to use thirteen different colored jams on the tart on this day for luck, creating a pastry resembling stained glass.[87]

Ethiopia and Eritrea[edit]

Orthodox priests dancing during the celebration of Timkat

In the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Church, the feast is known as Timkat and is celebrated on the day that the Gregorian calendar calls January 19, but on January 20 in years when New Year in the Ethiopian calendar falls on Gregorian September 12 (i.e. when the following February in the Gregorian calendar will have 29 days). The celebration of this feast features blessing of water and solemn processions with the sacred Tabot.[88]

Finland[edit]

In Finland, Epiphany is called loppiainen, a name which goes back to the 1600s. In the 1500s the Swedish-Finnish Lutheran church called Epiphany «Day of the Holy Three Kings», while before this, the older term Epiphania was used. In the Karelian language Epiphany is called vieristä, meaning cross, from the Orthodox custom of submerging a cross three times to bless water on this day.[89] Today, in the Lutheran church, Epiphany is a day dedicated to a focus on missionary work in addition to the Wise Men narrative. Between 1973 and 1991 Epiphany was observed in Finland on a Saturday each year no earlier than January 6, and no later than January 12. After that time however, the traditional date of January 6 was restored and has since been observed once again as a national public holiday.

The Christmas tree is traditionally taken out of the house on Epiphany. While the term loppiainen means «ending [of Christmas time],» in reality, Christmas celebrations in Finland are extended to Nuutti’s or St. Canute’s Day on January 13, completing the Scandinavian Twenty Days of Christmas.

Francophone Europe[edit]

In France people share one of two types of king cake. In the northern half of France and Belgium the cake is called a galette des Rois, and is a round, flat, and golden cake made with flake pastry and often filled with frangipane, fruit, or chocolate. In the south, in Provence, and in the south-west, a crown-shaped cake or brioche filled with fruit called a gâteau des Rois is eaten. In Romandie, both types can be found though the latter is more common. Both types of cake contain a charm, usually a porcelain or plastic figurine, called a fève (broad bean in French).[90]

The cake is cut by the youngest (and therefore most innocent) person at the table to assure that the recipient of the bean is random. The person who gets the piece of cake with the trinket becomes «king» or «queen» and wears a paper crown provided with the cake. In some regions this person has a choice between offering a beverage to everyone around the table (usually a sparkling wine or champagne), or volunteering to host the next king cake at their home. This can extend the festivities through all of January.[91]

German-speaking Europe[edit]

Traditional house blessing in chalk, written by Sternsinger on the door beam of the home

January 6 is a public holiday in Austria, three federal states of Germany, and three cantons of Switzerland, as well as in parts of Graubünden.

In the German-speaking lands, groups of young people called Sternsinger (star singers) travel from door to door. They are dressed as the Biblical Magi, and their leader carries a star, usually of painted wood attached to a broom handle. Often these groups are four girls, or two boys and two girls in order to sing in four-part harmony. They sing traditional songs and newer ones such as «Stern über Bethlehem». They are not necessarily three wise men. German Lutherans often note in a lighthearted fashion that the Bible never specifies that the Weisen (Magi) were men, or that there were three. The star singers solicit donations for worthy causes, such as efforts to end hunger in Africa, organized jointly by the Catholic and Protestant churches, and they will also be offered treats at the homes they visit.[92] The young people then perform the traditional house blessing, by marking the year over the doorway with chalk. In Roman Catholic communities this may even today be a serious spiritual event with the priest present, but among Protestants it is more a tradition, and a part of the German notion of Gemütlichkeit. Usually on the Sunday following Epiphany, these donations are brought into churches. Here all of the children who have gone out as star singers, once again in their costumes, form a procession of sometimes dozens of wise men and stars. The German Chancellor and Parliament also receive a visit from the star singers at Epiphany.[93]

Some Germans eat a Three Kings cake, which may be a golden pastry ring filled with orange and spice representing gold, frankincense and myrrh. Most often found in Switzerland, these cakes take the form of Buchteln but for Epiphany, studded with citron, and baked as seven large buns in a round rather than square pan, forming a crown. Or they may be made of typical rich Christmas bread dough with cardamom and pearl sugar in the same seven bun crown shape. These varieties are most typically purchased in supermarkets, with the trinket and gold paper crown included.[94] As in other countries, the person who receives the piece or bun containing the trinket or whole almond becomes the king or queen for a day. Epiphany is also an especially joyful occasion for the young and young at heart, as this is the day dedicated to plündern – that is, when Christmas trees are «plundered» of their cookies and sweets by eager children (and adults) and when gingerbread houses, and any other good things left in the house from Christmas, are devoured.[95] Lastly, there is a German rhyme saying, or Bauernregel, that goes Ist’s bis Dreikönigs kein Winter, kommt keiner dahinter meaning «If there hasn’t been any winter (weather) until Epiphany, none is coming afterward.» Another of these Bauernregel, (German farmer’s rules) for Epiphany states: Dreikönigsabend hell und klar, verspricht ein gutes Weinjahr or «If the eve of Epiphany is bright and clear, it foretells a good wine year.»

Greece, Cyprus[edit]

In Greece, Cyprus and the Greek diaspora throughout the world, the feast is called the Theophany,[96] or colloquially Phōta (Greek: Φώτα, «Lights»).[97] It is the «Great Celebration» or Theotromi. In some regions of Macedonia (West) it is the biggest festival of the year. The Baptism of Christ symbolizes the rebirth of man, its importance is such that until the fourth century Christians celebrated New Year on this day. Customs revolve around the Great Blessing of the Waters.[98] It marks the end of the traditional ban on sailing, as the tumultuous winter seas are cleansed of the mischief-prone kalikántzaroi, the goblins that try to torment God-fearing Christians through the festive season. During this ceremony, a cross is thrown into the water, and the men compete to retrieve it for good luck. The Phota form the middle of another festive triduum, together with Epiphany Eve, when children sing the Epiphany carols, and the great feast of St. John the Baptist (January 7 and eve),[99] when the numerous Johns and Joans celebrate their name-day.

It is a time for sanctification, which in Greece means expiation, purification of the people and protection against the influence of demons. This concept is certainly not strictly Christian, but has roots in ancient worship. In most parts of Greece a ritual called «small sanctification», Protagiasi or «Enlightment» is practiced on the eve of Epiphany. The priest goes door to door with the cross and a branch of basil to «sanctify» or «brighten» the rooms by sprinkling them with holy water. The protagiasi casts away the goblins ; bonfires are also lit in some places for that purpose. The «Great Blessing» happens in church on the day of the Epiphany. In the Churches in a special rig embellished upon which brought large pot full of water[clarify]. Then the «Dive of the Cross» is performed: a cross is throwned by the priest in the sea, a nearby river, a lake or an ancient Roman cistern (as in Athens). According to popular belief, this ritual gives the water the power to cleanse and sanitize. In many places, after the dive of the cross, the locals run to the beaches or the shores of rivers or lakes to wash their agricultural tools and even icons. Indeed, according common folk belief, icons lose their original strength and power with the passage of time, but they can be restored by dipping the icons in the water cleansed by the cross. This may be a survival of ancient beliefs. Athenians held a ceremony called «washing»: the statue of Athena was carried in procession to the coast of Faliro where it was washed with salt water to cleanse it and renew its sacred powers.

Today, women in many parts repeating this ancient custom of washing the images but combined with other instruments of medieval and ancient magic. As the plate of Mytilene while the divers dive to catch the Cross women at the same time «getting a detaining (= pumpkin) water from 40 waves and then with cotton dipped it clean icons without talking to throughout this process («dumb water») and then the water is thrown out of the not pressed (in the crucible of the church).[clarify][citation needed]

Guadeloupe Islands[edit]

Celebrations in Guadeloupe have a different feel from elsewhere in the world. Epiphany here does not mean the last day of Christmas celebrations, but rather the first day of Kannaval (Carnival), which lasts until the evening before Ash Wednesday. Carnival, in turn, ends with the grand brilé Vaval, the burning of Vaval, the king of the Kannaval, amidst the cries and wails of the crowd.[100]

India[edit]

Diyas (lights) are used to celebrate Epiphany in some Kerala Christian households.

In parts of southern India, Epiphany is called the Three Kings Festival and is celebrated in front of the local church like a fair. This day marks the close of the Advent and Christmas season and people remove the cribs and nativity sets at home. In Goa Epiphany may be locally known by its Portuguese name Festa dos Reis. In the village of Reis Magos, in Goa, there is a fort called Reis Magos (Wise Men) or Três Reis Magos for Biblical Magi. Celebrations include a widely attended procession, with boys arrayed as the Magi, leading to the Franciscan Chapel of the Magi near the Goan capital of Panjim.[101] Other popular Epiphany processions are held in Chandor. Here three young boys in regal robes and splendid crowns descend the nearby hill of Our Lady of Mercy on horseback towards the main church where a three-hour festival Mass is celebrated. The route before them is decorated with streamers, palm leaves and balloons with the smallest children present lining the way, shouting greetings to the Kings. The Kings are traditionally chosen, one each, from Chandor’s three hamlets of Kott, Cavorim and Gurdolim, whose residents helped build the Chandor church in 1645.

In the past the kings were chosen only from among high-caste families, but since 1946 the celebration has been open to all. Participation is still expensive as it involves getting a horse, costumes, and providing a lavish buffet to the community afterwards, in all totaling some 100,000 rupees (about US$2,250) per king. This is undertaken gladly since having son serve as a king is considered a great honor and a blessing on the family.[102]

Cansaulim in South Goa is similarly famous for its Three Kings festival, which draws tourists from around the state and India. Three boys are selected from the three neighboring villages of Quelim, Cansaulim and Arrosim to present the gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh in a procession. Only a native of these villages may serve as king; outsiders are barred from the role. Throughout the year, excitement runs high in the villages to see who will be chosen. The boys selected are meticulously groomed, and must grow their hair long in time for the festival. The procession involves the three kings wearing jeweled red velvet robes and crowns, riding white horses decked with flowers and fine cloth, and they are shaded by colorful parasols, with a retinue of hundreds.[103][104]

The procession ends at the local church built in 1581, and in its central window a large white star hangs, and colored banners stream out across the square from those around it. Inside, the church will have been decorated with garlands. After presenting their gifts and reverencing the altar and Nativity scene, the kings take special seats of honor and assist at the High Mass.[105]

The Saint Thomas Christians of Kerala State, Epiphany is known by its Syriac name Denha. Saint Thomas Christians, like other Eastern Christians, celebrate Denha as a great feast to commemorate the Baptism of Jesus in the river Jordan. The liturgical season Denhakalam («Weeks of Epiphany») commemorates the second revelation at the Baptism and the subsequent public life of Jesus. Denha is celebrated on January 6 by the Syro-Malabar Church in two ways – Pindiperunnal («Plantain trunk feast») and Rakkuliperunal («Feast with a night bath»).[106]

Ireland[edit]

The Irish call the day the Feast of the Epiphany or traditionally Little Christmas or «Women’s Christmas» (Irish: Nollaig na mBan). On Nollaig na mBan, women traditionally rested and celebrated for themselves after the cooking and work of the Christmas holidays. The custom was for women to gather on this day for a special meal, but on the occasion of Epiphany accompanied by wine, to honor the Miracle at the Wedding at Cana.[citation needed]

Today, women may dine at a restaurant or gather in a pub in the evening. They may also receive gifts from children, grandchildren or other family members on this day. Other Epiphany customs, which symbolize the end of the Christmas season, are popular in Ireland, such as the burning the sprigs of Christmas holly in the fireplace which have been used as decorations during the past twelve days.[107]

The Epiphany celebration serves as the initial setting for – and anchors the action, theme, and climax of – James Joyce’s short story «The Dead» from his 1914 collection, Dubliners.

Italy[edit]

In Italy, Epiphany is a national holiday and is associated with the figure of the Befana (the name being a corruption of the word Epifania), a broomstick-riding old woman who, on the night between January 5 and 6, brings gifts to children or a lump of «coal» (really black candy) for the times they have not been good during the year. The legend told of her is that, having missed her opportunity to bring a gift to the child Jesus together with the Biblical Magi, she now brings gifts to other children on that night.[108][109][24]

However, in some parts of today’s Italian state, different traditions exist, and instead of the Befana it is the three Magi who bring gifts. in Sardinia, for example, where local traditions and customs of the Hispanic period coexist, the tradition of the Biblical Magi (in Sardinian language, Sa Pasca de is Tres Reis) bringing gifts to children is very present.

Jordan[edit]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Al-Maghtas ruins on the Jordanian side of the Jordan River, believed to be the location where Jesus of Nazareth was baptised by John the Baptist |

|

| Location | Balqa Governorate, Jordan |

| Reference | 1446 |

| Inscription | 2015 (39th Session) |

| Website | www.baptismsite.com |

Thousands of Jordanian Christians, tourists and pilgrims flock to Al-Maghtas site on the east bank of the Jordan River in January every year to mark Epiphany, where large masses and celebrations are held.[110] «Al-Maghtas» meaning «baptism» or «immersion» in Arabic, is an archaeological World Heritage site in Jordan, officially known as «Baptism Site «Bethany Beyond the Jordan» (Al-Maghtas)». It is considered to be the original location of the Baptism of Jesus and the ministry of John the Baptist and has been venerated as such since at least the Byzantine period.[8]