- Hamburger Dom

-

m

«Гамбургский собор»

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь.

2014.

Смотреть что такое «Hamburger Dom» в других словарях:

-

Hamburger Dom — steht für: die 1805 abgebrochene ehemalige Domkirche, siehe Mariendom (Hamburg) die Bischofskirche des 1995 wiedererrichteten Erzbistums Hamburg, siehe Neuer Mariendom (Hamburg) ein Volksfest in Hamburg, siehe Hamburger Dom (Volksfest) … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Hamburger Dom (Volksfest) — Eingang zum Hamburger Dom Der Hamburger Dom ist ein regelmäßig auf dem Heiligengeistfeld in Hamburg stattfindendes Volksfest. Jährlich besuchen mehrere Millionen Menschen die Veranstaltung, die dreimal im Jahr stattfindet als: Winterdom (Dom… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

DOM — ist eine Bezeichnung für: Dom, Bezeichnung bedeutender Kirchen, siehe Kathedrale #Dom eine Ethnie im Nahen Osten, siehe Domari Dampfdom, eine Einrichtung zur Entnahme des Dampfes aus einem Dampfkessel Federbeindom, den Teil der Karosserie eines… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

DoM — ist eine Bezeichnung für: Dom, Bezeichnung bedeutender Kirchen, siehe Kathedrale #Dom eine Ethnie im Nahen Osten, siehe Domari Dampfdom, eine Einrichtung zur Entnahme des Dampfes aus einem Dampfkessel Federbeindom, den Teil der Karosserie eines… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Dom — steht für: eine Kirche herausragender Bedeutung, siehe Kathedrale#Dom davon abgeleitet: Der Dom (Buchreihe), Buchreihe Der Dom (Zeitschrift), die Kirchenzeitung für das Erzbistum Paderborn Der Dom (Gertrud von le Fort), Erzählung Hamburger Dom… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Hamburger Nikolaikirche — St. Nikolai Kirche Der Glockenturm der „alten“ Nikolaikirche … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Dom de Beern — (* 17. Juni 1927 in Hamburg; † 29. März 1988 in Düsseldorf) war ein deutscher Film und Theaterschauspieler. De Beern wurde als Sohn eines Holländers in Hamburg geboren. Nachdem er die Schule absolvierte und ein Studium des Chemieingenieurwesen in … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Hamburger Anglikaner — Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Christentum 1.1 Christentum im Mittelalter 1.2 Evangelische Kirche 1.2.1 Reformation 1.2.2 Neuzeit 1.2.3 Evangelisch reformierte Kirchen … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Dom St. Nikolai (Greifswald) — Greifswald, Dom St. Nikolai Innenansicht richtung Chor Der Greifswalder Dom S … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Hamburger Glockenlager — Glockenfriedhof 1947 Glockenfriedhof im Freihafen Der „Glock … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Dom zu Visby — Sankt Maria Domkyrka Der Dom zu Visby, der auch unter dem ursprünglichen Namen Sankt Maria Kirche bekannt ist, ist die einzige verbliebene mittelalterliche Hauptkirche der alten Hansestadt Visby auf der schwedischen Insel Gotland. Sie ist seit… … Deutsch Wikipedia

Одним из главных открытий моего первого «немецкого» года стало осознание того, насколько сильно в Германии любят праздники. Всевозможные ярмарки, фестивали, праздничные парады и многое другое. Несмотря на то, что у многих людей Германия ассоциируется со строгостью, порядком и однозначно чем-то невесёлым, «гуляют» здесь куда больше, нежели в странах бывшего Советского Союза. Это правда: многих жителей здесь хлебом не корми – дай потусить на ярмарке или поглазеть на фейерверк. Кстати, оба эти слова пришли в русский язык как раз из немецкого.

При всём вышесказанном, такое впечатление у меня сложилось даже несмотря на то, что я нахожусь в северной части Германии – традиционно более спокойном и чопорном регионе, нежели юг страны, который действительно умеет веселиться от души.

История фестиваля «Hamburger Dom» (далее будем называть его просто Dom) уходит своими корнями в далёкое средневековье, когда люди ещё пили воду прямо из рек, бегали босиком по свежей росе, а чуму лечили припарками. В середине 11 века около главного гамбургского собора (а «Dom» по-немецки как раз и означает «собор») время от времени начали собираться различные торговцы, ремесленники, мастера-затейники, развлекавшие непритязательную публику тех лет и, конечно же, различные мошенники. Изначальной целью торговцев, которые первыми обосновались возле собора, была возможность торговать в плохую погоду.

Прошли десятилетия и торгово-развлекательное мероприятие переросло в полноценную ярмарку, которую немцы безумно любили уже в те времена. Несмотря на это, подобные гуляния пришлись не по душе руководству церкви, которая в 1334 году запретило проводить «под крылом» одного из главнейших храмов региона ярмарки. Однако стоит отметить, что к тому моменту всё происходящее на ярмарке действительно выходило далеко за пределы религиозных устоев церкви.

Запрет ярмарки пришёлся жителям Гамбурга явно не по душе. Иначе чем ещё можно объяснить то, что уже спустя 3 года торговцам снова разрешили вернуться на прежнее место? Правда, с один условием: торговать там можно было только во время сильной непогоды, как и задумывалось изначально.

Размеренная жизнь ярмарки продолжалась вплоть до начала 19 века, когда в 1804 году городскими властями было принято решение снести старейший собор Гамбурга, построенный ещё в первой половине 9 века. Причина оказалась до боли банальна: храм занимал очень много места в центре города, который уже тогда страдал от нехватки свободных территорий, и меркантильные власти решили заработать на продаже земли и сдаче её в аренду. Так Гамбург лишился своего самого красивого сооружения (а заодно и ещё 5 средневековых церквей), который сейчас вполне мог бы считаться одним из интереснейших во всей Германии.

После разрушения собора ярмарка потеряла своё постоянное пристанище и стала кочевать с одной площади на другую. Тем не менее, место, на котором некогда находился вышеупомянутый храм, так и не смогло надолго стать домом для кого бы то ни было: уже в конце 19 века все постройки были снесены, а ярмарка вернулась на свою историческую территорию.

Нынешний свой вид Dom приобрёл уже после Второй мировой войны, когда фестиваль стал проводиться трижды в год. Сейчас это весенний Dom (20 марта – 19 апреля), летний Dom (24 июля – 23 августа) и зимний Dom (7 ноября – 7 декабря).

На данный момент Dom является крупнейшим фестивалем северной Германии, принимающим более 10 миллионов посетителей в год. Здесь важно не перепутать его с бременским Фраймарктом, который старее, но далеко не крупнейший.

В отличие от Рождественских ярмарок, Dom – это, в первую очередь, аттракционы и развлечения.

Есть карусели как для больших…

…так и для самых маленьких.

Отдельного упоминания заслуживают автоматы с различными игрушками и жетонами, из которых буквально толпы людей пытаются что-то вытянуть.

Впрочем, в любом деле есть свои профессионалы. При мне группа из трёх человек за несколько минут нащёлкала в подобном автомате столько жетонов, что их хватило бы на приличный приз из разряда домашней техники.

Мир панд.

Аттракционы – аттракционами, но Германия не была бы собой самой, если бы на таком масштабном фестивале было негде перекусить (и выпить, само собой). Но, как можно видеть по скучающим продавцам, еда здесь – не главный атрибут праздника.

Особой красотой отличаются местные павильоны. Вот как после этого можно гулять среди натяжных белых палаток?

Атмосфера на фестивале праздничная, посетители ведут себя добропорядочно. Несмотря на повсеместную продажу алкоголя, я не увидел ни то что ни одного «синего» конфликта, но и даже ни одного сильно пьяного человека. Всё крайне прилично, а родители не боятся приходить сюда с маленькими детьми даже после 10 часов вечера.

Фестиваль имеет одну замечательнейшую традицию: каждую пятницу в 22:30 здесь устраивают красочный фейерверк. При этом не несколько выстрелов дешёвой петарды, а полноценный салют, сравнимый с тем, что устраивают в некоторых странах на Дни независимости.

P.S. Я впервые решил поснимать фейерверк, и, как видно выше, получилось это не слишком хорошо. В связи с этим у меня возник вполне закономерный вопрос: как фотографировать фейерверки? Какие есть нюансы такой съёмки? Мастера-фотографы, поделитесь опытом!

Подводя итог: несмотря на сезонность, Dom – одно из главный достопримечательностей Гамбурга. Весёлое времяпрепровождение и вкусные национальные закуски станут несомненно выгодной альтернативой скучному вечеру в гостинице!

Как добраться:

Hamburger Dom находится буквально возле одного из выходов со станции метро St. Pauli (ветка U3). Время в пути от центрального вокзала – 9 минут.

* * *

Иногда я пишу крутые посты. Чтобы не пропустить их, подписывайтесь на мой блог.

Кроме того, я присутствую и в других соцсетях:

Twitter // Instagram // Facebook // VK

| Hamburg Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of St. Mary’s Sankt Mariendom Dom St. Marien zu Hamburg |

|

St. Mary’s Cathedral |

|

|

Hamburg Cathedral Location within Hamburg Hamburg Cathedral Hamburg Cathedral (Germany) |

|

| 53°32′57″N 09°59′52″E / 53.54917°N 9.99778°ECoordinates: 53°32′57″N 09°59′52″E / 53.54917°N 9.99778°E | |

| Location | Hamburg Old Town |

| Country | Germany |

| Denomination | Lutheran |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic till 1531 |

| History | |

| Status | Proto-cathedral |

| Founded | 831 |

| Founder(s) | Ansgar |

| Dedication | Mary of Nazareth |

| Consecrated | 18 June 1329 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Demolished |

| Architectural type | 5-naved hall church |

| Style | Brick Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1035 |

| Closed | 1531–1540 |

| Demolished | 1804–1807 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | brick |

| Administration | |

| Province | Bremen |

| Archdiocese | Bremen |

Saint Mary’s Cathedral in Hamburg (German: Sankt Mariendom, also Mariendom, or simply Dom or Domkirche, or Hamburger Dom) was the cathedral of the ancient Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hamburg (not to be confused with Hamburg’s modern Archdiocese, est. 1994), which was merged in personal union with the Diocese of Bremen in 847, and later in real union to form the Archdiocese of Hamburg-Bremen, as of 1027.

In 1180 the cathedral compound turned into the cathedral close (German: Domfreiheit; i.e. cathedral immunity district), forming an exclave of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen within the city of Hamburg. By the Reformation the concathedral was converted into a Lutheran church. The cathedral immunity district, since 1648 an exclave of the Duchy of Bremen, was seized by Hamburg in 1803. The city then prompted the demolition of the proto-cathedral between 1804 and 1807.

Location[edit]

The cathedral, in common Italo-Nordic tradition simply called Dom (Italian: Duomo), which is the synecdoche, used – pars pro toto – for most existing or former collegiate churches and cathedrals in Germany alike.[1] The cathedral was situated in the section of the earliest settlement of Hamburg on a geest hill between the rivers Alster and Elbe near Speersort [de] street. Today’s St. Peter’s Church was erected right north of the Dom, today’s Domstraße crosses through the former site of the cathedral. Curienstraße recalls the location of the canons’ courts.

History[edit]

The early history of the Hamburg See and its first cathedral buildings is somewhat obscured. In different struggles on competences and privileges plenty of documents have been completely forged or counterfeited or backdated, in order to corroborate arguments. «These forgeries have drawn a veil before the early history of the [archbishopric of] Hamburg-Bremen.»[2] Results of archeological excavations could not clarify the succession of early cathedral buildings before 1035.

Ansgar, founder of St. Mary’s, copy of a depiction, originally hung in the cathedral, now in St. Peter’s.

A wooden mission church is reported for 831. Pope Gregory IV appointed the Benedictine monk Ansgar as first archbishop as of 834. After the looting of Hamburg and the destruction of the church by Vikings under Horik I in 845 the archdiocese was united with the Diocese of Bremen in 847. Hamburg remained the archiepiscopal seat.

The deposed Pope Benedict V was carried off to Hamburg in 964 and placed under the care of Archbishop Adaldag. He became a deacon then but died in 965 or 966 and was buried in the cathedral.[3] In 983 Prince Mstivoj of the Obodrites destroyed city and church. In 988 Benedict’s remains were presumably transferred to Rome. Archbishop Unwan started reconstructing a fortified cathedral.[4] Under Archbishop Adalbert of Hamburg (1043–1072) Hamburg-Bremen attained its greatest prosperity and later had its deepest troubles. Adalbert was after Hamburg-Bremen’s upgrade to the rank of a Patriarchate of the North and failed completely. Hamburg was even dropped as part of the diocesan name.

With the investiture of Archbishop Liemar the seat definitely moved to Bremen. However, the cathedral chapter of Hamburg persisted with several special rights. Around 1035 Archbishop Adalbrand of Bremen [de] prompted the construction of a first cathedral from brick and his castle.[5] In the same century St. Peter’s Parish Church was established north of the cathedral compound.

However, starting in 1245 Adalbrand’s structure was replaced by a new early Gothic three-naved hall church erected by chapter and Prince-Archbishop Gebhard of Lippe [de], one of the few incumbents of the united see looking for a balanced performance in Bremen and Hamburg, preferring the title Bishop of Hamburg when staying in the diocesan territory right of the Elbe, as is known from seals and documents.[6] Prince-Archbishop Burchard Grelle consecrated the church as archdiocesan concathedral on 18 June 1329.

By the end of the 14th century the concathedral was extended by two more naves. After this, the concathedral remained mostly unchanged until its demolition by 1807. The tower was completed in 1443. In the early 16th century an additional hall, first mentioned as the Nige Gebuwte (Low Saxon for new building) in 1520, was erected closing the adjacent cloister towards the north. This hall was presumably used for sermons, the actual cathedral for masses. The hall was later colloquially called Schappendom after the cupboards (Low Saxon: Schapp[en] [pl.] [de]), which carpenters of Hamburg exhibited there. The traditional fayre at Christmas, recorded for the square in front of the cathedral since the 14th century, and continued as today’s funfayre Hamburger Dom (literally in Hamburg Cathedral), then used to take place within the Schappendom hall.

Starting in 1522 Lutheranism spread among the burghers of Hamburg, gaining their vast majority by 1526, while most canons of the cathedral chapter rather clung to Catholicism, enjoying their extraterritorial status. Hamburg’s Senate (city government) accounted for the new facts and adopted the new denomination in 1528. So when in October 1529, the senate – wielding its advowson – appointed Johannes Aepinus (d. 1553) as Lutheran pastor at the neighbouring St. Peter’s Church, in order to introduce Johannes Bugenhagen’s Lutheran Church Order in the city, Aepinus contested with the prevailingly Catholic cathedral chapter.[7]

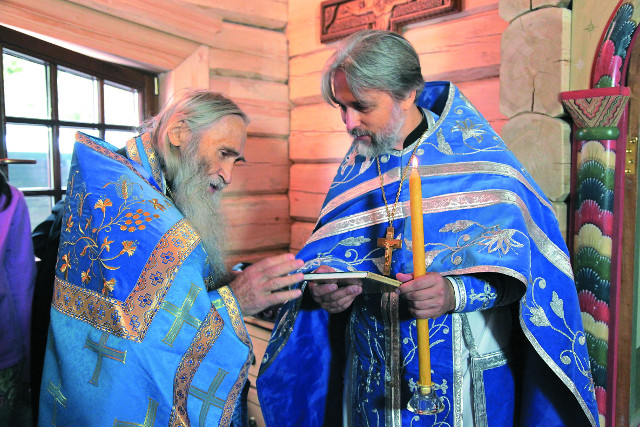

St. Mary’s Cathedral in 1800, seen from south against the towers of St. Peter (centre) and St. James (right).

The extraterritorial status and the denominational opposition strengthened the perception of cathedral, chapter, and immunity district as alien element within the city. While almost all inhabitants outside the immunity district had become parishioners of the now Lutheran parish churches, the huge cathedral lacked a congregation. Between the Feast of the Assumption of Mary and December 1529 the city’s militia barred churchgoers from access to the cathedral, given up after imperial protests.[8] Furthermore, the capitular estates in Hamburg and spread all over the North Elbian diocesan area, forming the endowment to maintain canons and cathedral, were increasingly withheld by the respective territorial rulers. Thus in May 1531 the chapter closed the cathedral and its maintenance was neglected.[8]

Meanwhile, the majority of the capitular canons had adopted Lutheranism and elected fellow faithful to eventual vacancies. The cathedral reopened as Lutheran place of worship in 1540. The disputes on capitular estates were regulated by the Bremen Settlement in 1561. The church turned into a Lutheran proto-cathedral and the remaining endowment allowed financing excellent ecclesiastical music, making the proto-cathedral a frequented venue for Lutheran services accompanied by music. The incumbents of the Bremen See used to be themselves Lutherans since the accession of Administrator Henry of Saxe-Lauenburg in 1569. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 transformed the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen, an elective monarchy, into the hereditary monarchy of the Duchy of Bremen, in personal union with Sweden until 1712/15, since 1715 with the House of Hanover. Thus the immunity district turned into a ducal Bremian enclave in the city.

Hamburg Cathedral, seen from east, during demolition in 1806

The architect Ernst Georg Sonnin [de] carried out maintenance works in 1759/1760. Due to the weak, unstable subsoil the cathedral tower was leaning, so Sonnin straightened the tower, as he had done with other church towers in Hamburg, he even demonstrated the gathered public his new technique by reversing it to leaning and again straightening it.[9] Since 1772 the city of Hamburg considered to buy the immunity district, however, not effectuating any changes by then. On the instigation of the ducal Bremian government the cathedral chapter sold its valuable library by the end of the 18th century. Since 1790 the pastorate of the proto-cathedral remained vacant.

By the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss in 1803, the Duchy of Bremen ceded its cathedral immunity districts in Bremen [de] and Hamburg, to these free imperial cities. With the neglect of the proto-cathedral by the ducal government it had dropped out of Hamburg’s cultural life again. Hamburg’s Senate, then holding the ius patronatus to all other Lutheran parish churches had no usage for an additional church, which did not even have the parishioners to maintain it. So in 1802, the Senate, always upholding the city’s vital mercantile interests, ordered Hamburg’s Gothic proto-cathedral to be pulled down, a decision which aroused no serious opposition within the city and which was carried out between 1804 and 1807.

The stones were sold off or used to reinforce the sea defenses along the Elbe; the funerary sculptures and monuments were broken up and used in the reconstruction of the city’s rudimentary sewage system. The Senate was partly motivated by the desire to rid the city of an extraterritorial institution, but it is more than possible that the rise in rents and the high demand for housing at the time also played a role. In any case, the incident was typical of the celebrated Philistinism of the Hamburg authorities. Five more medieval churches in the city were pulled down between 1807 and 1837.[10]

Legacy[edit]

Rescued furnishings[edit]

There was little interest in the valuable furnishings of the proto-cathedral. Few enthusiasts with interest in the history of art did not prevail as to rescuing the building. In order to make the biggest bargain not only the structures above earth have been demolished and sold as construction material but even the grave slabs and most of the fundaments have been dug out to be sold alike. The more than 370 slabs of sandstone have mostly been built in hydraulic structures along the many waterways in Hamburg, broken stones and rubble were used for dikes in Ochsenwerder and Spadenland.[11] So archeological excavations in recent years could not even uncover the exact groundplan.[12]

The rescue of some furnishings we owe to Philipp Otto Runge, prevailing in the merchant republic of Hamburg with the argument, that they could be sold as well. So the Late Gothic cathedral altarpiece, created by Hamburg’s famous artists Absolon Stumme and his stepson Hinrik Bornemann, however, only finished, after their deaths in 1499, by Wilm Dedeke were rescued and sold to East Prussia. In 1946 the altarpiece was nationalised and is now shown in the National Museum, Warsaw.

The congregation of Hamburg’s St. James the Greater Church acquired the St. Luke Altar from the furnishings of the proto-cathedral, now presented in the second southern nave of St. James. Several 15th-century stained glass windows of the apostles were sold to the Catholic congregation of Ludwigslust and are now built in the quire of Ss. Helena and Andrew Church [de], erected 1803–1809.

One of the cathedral bells survived. The Celsa, founded by the bell founder Gerhard van Wou in his workshop on Glockengießerwall in 1487, was bought in 1804 by the Lutheran congregation of St. Nicholas Church [de] in Altengamme, now a part of Hamburg.[13]

Remnants of Pope Benedict V’s cenotaph, which was erected around 1330, but removed in 1782, have been found, besides other findings, in the excavation campaigns (1947–1957, 1980–1987 and 2005–2007).[14]

Hamburger Dom[edit]

A fair held in or in front of the cathedral was first recorded in 1329, at the beginning only at special feasts like Christmas, thus being one of the predecessors of today’s Christmas markets. With the Reformation in the 16th century the fair was also held on other occasions. After the demolition of the cathedral (1804–1807), the fair, still named Hamburger Dom (literally in English: Hamburg Cathedral) moved to Gänsemarkt square (geese market) in 1804, and takes place on Heiligengeistfeld since 1892.

The cathedral site after its demolition[edit]

Former cathedral site with the archeological park and the steel imitations of the walls of the presumable original fortified church, St. Peter’s in the background.

After its demolition the cathedral site remained empty until Carl Ludwig Wimmel and Franz Gustav Forsmann [de] erected a new building between 1838 and 1840 for Hamburg’s most renowned Gymnasium, the Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums. This building was later given to Hamburg’s State and University Library [de], but destroyed in the Allied Bombing Operation Gomorrah in summer 1943. Since the rubble was cleared in 1955 the site remained again empty, crossed by a new thoroughfare named Domstraße (Cathedral Street).

A recent project to rebuild the site with a modern glass steel complex has been dropped after civic protest in 2007. Since 2009 an archeological park covers the site.[15] Steel elements indicate the former walls of the early fortified church supposed to have been the original form of the archiepiscopal see. 39 white benches indicate the likely locations of the former columns of the 5-naved main hall. A single found fundament of one of them can be seen through a glass screen.[16]

Modern Hamburg Cathedral[edit]

In 1994 a new Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hamburg was founded. On this occasion the 1893-erected Catholic St. Mary’s Church in Sankt Georg neighbourhood became the New St. Mary’s Cathedral.

Notable people active at the Dom[edit]

Archbishops, prince-archbishops and administrators[edit]

The incumbents of the Hamburg-Bremen See were usually titled Archbishop of Hamburg and Bishop of Bremen between 848 and 1072, thereafter Hamburg was mostly dropped as titular element, however, some later archbishops continued the tradition of naming both dioceses until 1258. The Lutheran incumbents holding the see since 1569, were officially titled Administrators, but, nevertheless, colloquially referred to as prince-archbishops.

Chapter and canonry[edit]

The cathedral chapter was founded in 834 and its members, the canons (Domherr[en]) enjoyed personal immunity from jurisdiction of the secular local rulers. The chapter wielded the ecclesiastical jurisdiction in the North Elbian part of the archdiocese, to wit Hamburg, Ditmarsh, Holstein, and Stormarn. Thus until the breakthrough of the Reformation the chapter appointed the priests serving in the city’s parishes. Cathedral, chapter and canonry were maintained by numerous prebends comprising urban real estate and feudal dues and soccage collected from dependent farmers in many so-called capitular villages in the afore-mentioned areas. Holsatian aristocracy and Hamburg’s patriciate provided for most of the canons.

At Archbishop Adalgar’s (888–909) instigation Pope Sergius III confirmed the amalgamation of the Diocese of Bremen with the Archdiocese of Hamburg to form the Archdiocese of Hamburg and Bremen, colloquially called Hamburg-Bremen, and by so doing he denied Cologne’s claim as metropolis over Bremen. Sergius prohibited Hamburg’s Chapter to found suffragan dioceses of its own. After the Obodrite destruction of Hamburg in 983 the chapter was dispersed. So Archbishop Unwan appointed a new chapter with twelve canons, with three each taken from Bremen Cathedral chapter, and the three colleges of Bücken, Harsefeld and Ramelsloh.[4] In 1139 Archbishop Adalbero had fled the invasion of Rudolph II, Count of Stade and Frederick II, Count Palatine of Saxony [de], who destroyed Bremen, and established in Hamburg also appointing new capitular canons by 1140.[17]

With the archdiocese gaining princely sovereignty as an imperial estate of the Holy Roman Empire in 1180, the compounds of the Hamburg and Bremen cathedrals with chapterhouses and capitular residential courts (German: Curien) turned into Cathedral Immunity Districts (German: Domfreiheiten), forming exclaves of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen of imperial immediacy. After the Bremen Cathedral chapter, overlooking the three enfranchised Hamburg capitulars, had elected Valdemar of Denmark archbishop in 1207, Bremen’s cathedral dean Burchard of Stumpenhusen, who had opposed this election, fled to Hamburg, then under Danish influence.[18] King Valdemar II of Denmark, in enmity with his father’s cousin Archbishop Valdemar, gained the Hamburg chapter to elect Burchard as anti-archbishop in early 1208. Lacking papal support King Valdemar II himself invested him as Archbishop Burchard I, however, only accepted in North Elbia.[18]

In 1219 the Bremen Chapter again ignored the Hamburg capitulars, fearing their Danish partisanship and elected Gebhard of Lippe [de] archbishop.[19] In 1223 Archbishop Gebhard reconciled the Hamburg chapter and stipulated that three of its capitulars were enfranchised to elect with the Bremen chapter, to wit the provost, presiding the chapter, the dean (Domdechant) and the magister scholarum, in charge of the education at the cathedral school.[20] Pope Honorius III confirmed this settlement in 1224, also affirming the continued existence of both chapters.[20]

Canons were distinguished as younger (canonicus minor) and older (canonicus maior) office holders. The distinction was also evidenced by lower and higher prebends. Johann Rode the Elder served as provost between 1457 and 1460.[21] The known historian Albert Krantz, also serving the city of Hamburg as diplomat, gained a canonicate of the lector primarius in 1493.[22] In 1508 he advanced to Cathedral Dean (Domdechant) of the chapter.[22] Krantz applied himself with zeal to the reform of ecclesiastical abuses, but, though opposed to various corruptions connected with Catholic church discipline, he had little sympathy with the drastic measures of John Wycliffe or Jan Hus. Krantz generally agreed with Martin Luther’s protest against the abuse of indulgences, but refused Luther’s theses on his deathbed in December 1517.

One canonicate, called magister scholarum, was in charge of the education at the cathedral school. 1499 Heinrich Banzkow [de] served as magister scholarum, Johannes Saxonius [de] was appointed magister scholarum in 1550. After the breakthrough of the Reformation canonicates were not necessarily bound to ecclesiastical offices any more, but often served to maintain educators, musicians or scientists.

In 1513 the Ditmarsians founded a Franciscan Friary in Lunden to thank their then national saint patron Mary of Nazareth, fulfilling a vow taken before the Battle of Hemmingstedt in case they could defeat the Dano-Holsatian invaders, however, the Hamburg chapter demanded its say in appointing the prebendaries.[23] After years of dispute, the Council of the 48, the elected governing body of the farmers’ republic of Ditmarsh, decided to found a Gallicanist kind of independent Catholic Church of Ditmarsh in August 1523, denying Hamburg’s capitular jurisdiction in all of Ditmarsh.[24] The chapter could not regain the jurisdiction, including its share in ecclesiastical fees and fines levied in Ditmarsh.[25]

On request of the Senate of Hamburg Luther had sent Bugenhagen to the city. He developed the Lutheran Church Order for Hamburg in 1529. He first aimed at seizing the revenues of concathedral and chapter in favour of the common chest of the urban parishes, financing pastors and teachers. The chapter would be dissolved and the released canons paid a life annuity. However, the then still steadfastly Catholic capitulars refused and were not to be forced due to their immunity and extraterritorial status.

The dispute made many canons leave the city and shut down the concathedral. A lawsuit in the matter was still pendent at the Imperial Chamber Court when after the Smalkaldic War and the subsequent Peace of Augsburg Emperor Ferdinand I brokered the Bremen Settlement in 1561.

Two prebends, privately donated in the 15th century, were reserved for lectors (lector primarius, secundarius) in charge of the advanced theological training of the clergy. After the Reformation the lector primarius was combined with the superintendency of the Lutheran Church of Hamburg, first held by Superintendent Aepinus since 18 May 1532. The lector secundarius was combined with the Lutheran pastorate at the Dom. Smaller prebends were reserved to maintain church musicians and teachers. Known pastors were, among others, Johannes Freder [de] (1540–1547), Paul von Eitzen [de] (as of 1548[26]), and Johann Heinrich Daniel Moldenhawer [de] (1765–1790).

With the Peace of Westphalia the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen had turned from an elective monarchy into the hereditary monarchy of the Duchy of Bremen. While the cathedral chapters of Bremen and Hamburg were not dissolved as such, they sharply lost influence because they used to be the election bodies of the incumbents of the see securing their privileges and endowments by election capitulations, which the incumbents had to issue as self-commitments to the laws and principles established until their accession. Hereditary monarchy opened the gate for absolutism in the Duchy of Bremen. The chapters turned from constitutive legislative bodies into subordinate administrative units receiving orders from the rulers. The last canon officiating as president of the chapter was the jurist Friedrich Johann Lorenz Meyer [de].

Church musicians[edit]

Many church musicians were granted prebends or canonicates, traditionally one canon, titled cantor or precentor, was in charge of preparing and organising musical performances in the Dom. Since the Reformation the Senate of Hamburg furthered the cantorate of the Johanneum surpassing the church music of the Dom. At times both cantorates were held in personal union.

Erasmus Sartorius [de], vicar at the Dom since 1604, was entrusted the cantorate of Johanneum in 1628. Cathedral cantor Thomas Selle officiated between 1642 and 1663. Johann Wolfgang Franck held the cantorate from 1682 to 1685. Friedrich Nicolaus Bruhns, succeeding Nicolaus Adam Strungk in charge of the Hamburger Ratsmusik (Music for the Hamburg Senate) in 1682, became canonicus minor and cathedral cantor in 1687.

Johann Mattheson, diplomat, musician, music theoretician, and cathedral cantor between 1715 and 1728 was the first author to publish on Johann Sebastian Bach.[27] Deafness forced Mattheson to retire. He was succeeded by Reinhard Keiser, who became the cathedral precentor in 1728, and wrote largely church music there until his death in 1739. Between 1756 and 1762 Johann Valentin Görner served as cantor.

Capitular endowment[edit]

The capitular endowment comprised 14 so-called capitular villages (Kapitelsdörfer) outside of then Hamburg, paying dues to the chapter. Following the Reformation the rulers of Holstein seized these villages, legitimised by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. On 18 October 1576 Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp seized a number of capitular endowments against a recurrent annuity paid until 1803.

Endowments:

- The tithe of Ahrensfelde since 1195

- The tithe of Bargfeld since 1195

- Half a hide in Barmbek

- Barmstedt till 1564

- Barsbüttel, grain dues from the village since 1306, all the village since 7 April 1341, till 1576

- Bergstedt [de] since 1345

- Part of Bramfeld since 1271

- The tithe of Duvenstedt since 1255

- Hoisdorf since 1339, till 1576

- Half the tithe of Kirchsteinbek since 1255

- The tithe of Klein Borstel [de] still in 1540

- Meiendorf [de] since 1318

- Two oxgangs in Mellingstedt since 1271

- Domherrenland (canons’ land) in Moorburg [de], till 1803

- An estate in Niendorf since 1343

- Osdorf since the early 14th century

- Half the tithe of Oststeinbek since 1255, the local mill since 1313, till 1576

- Papendorf in Holstein, held by the chapter between 1256 and 1556

- Seven oxgangs and three cottages in Poppenbüttel since 1336, all the village since 1389

- Dues from Rahlstedt since 1296

- Rellingen till 1564

- The tithe of Rissen since 1255

- Stemwarde part of its forest in 1259, all the village since 22 June 1263, till 1576

- A recurrent rent from Stockelsdorf manor since 1358

- Todendorf since 1263

- Willinghusen half the village since 1238, all the village since 1342, till 1576

- Wulfsdorf

- Wulksfelde

References[edit]

- Ralf Busch, Hamburg Altstadt, Stuttgart: Theiss, 2002, (=Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Deutschland; vol. 41).

- Adolf Hofmeister, «Der Kampf um das Erbe der Stader Grafen zwischen den Welfen und der Bremer Kirche (1144–1236)», in: Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser: 3 vols., Hans-Eckhard Dannenberg and Heinz-Joachim Schulze (eds.) on behalf of the Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 1995 and 2008, vol. I ‘Vor- und Frühgeschichte’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5), vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2), vol. III ‘Neuzeit’ (2008; ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9), (=Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden; vols. 7–9), vol. II: pp. 105–157.

- Kai Mathieu, Der Hamburger Dom, Untersuchungen zur Baugeschichte im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert (1245–1329) und eine Dokumentation zum Abbruch in den Jahren 1804 – 1807, Hamburg: Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte, 1973.

- Friedrich Johann Lorenz Meyer, Blick in die Domkirche in Hamburg, Hamburg: Nestler, 1804.

- Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Die Grafen von Stade und die Erzbischöfe von Bremen-Hamburg vom Ausgang des 10. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts», in: Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser: 3 vols., Hans-Eckhard Dannenberg and Heinz-Joachim Schulze (eds.) on behalf of the Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 1995 and 2008, vol. I ‘Vor- und Frühgeschichte’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5), vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2), vol. III ‘Neuzeit’ (2008; ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9), (=Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden; vols. 7–9), vol. II: pp. 43–104.

- Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Geschichte der Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Elbe und Weser vom Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts», in: Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser: 3 vols., Hans-Eckhard Dannenberg and Heinz-Joachim Schulze (eds.) on behalf of the Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 1995 and 2008, vol. I ‘Vor- und Frühgeschichte’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5), vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2), vol. III ‘Neuzeit’ (2008; ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9), (=Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden; vols. 7–9), vol. II: pp. 1–21.

- Michael Schütz, «Die Konsolidierung des Erzstiftes unter Johann Rode», in: Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser: 3 vols., Hans-Eckhard Dannenberg and Heinz-Joachim Schulze (eds.), Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 1995 and 2008, vol. I ‘Vor- und Frühgeschichte’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5), vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2), vol. III ‘Neuzeit’ (2008; ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9), (=Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden; vols. 7–9), vol. II: pp. 263–278.

- Ferdinand Stöter, Die ehemalige St. Marien Kirche oder der Dom zu Hamburg in Bildern mit erläuternden Texten von F. Stöter, Hamburg: Gräfe, 1879.

External links[edit]

- Daten zur Geschichte des Hamburger Mariendoms

Notes[edit]

- ^ Therefore the uniform translation of these terms into English as cathedrals may not always be appropriate.

- ^ The original quotation: «Diese Fälschungen haben einen Schleier vor die Frühgeschichte Hamburg-Bremens gezogen.» Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Geschichte der Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Elbe und Weser vom Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II: Mittelalter (1995), pp. 1–21, here p. 6. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2. Addition in edged brackets not in the original.

- ^ Erich Verg and Martin Verg, Das Abenteuer, das Hamburg heißt, Hamburg: Ellert & Richter, 42007, p. 15. ISBN 978-3-8319-0137-1.

- ^ a b Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Die Grafen von Stade und die Erzbischöfe von Bremen-Hamburg vom Ausgang des 10. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 43–104, here p. 53. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Die Grafen von Stade und die Erzbischöfe von Bremen-Hamburg vom Ausgang des 10. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 43–104, here p. 54. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ However, he already accounted for the reversion of the original ranking using left of the river Elbe the title Archbishop of Bremen.

- ^ This contest gave rise to his Ioannis Hepini Pinacidion de Romanæ ecclesiæ imposturis et Papisticis sutelis/ aduersus impudentem Hamburgensium Canonicorum autonomiam, Hamburg: Georg Richolff the Younger, 1530.

- ^ a b Jana Jürgs, Der Reformationsdiskurs der Stadt Hamburg: Ereignisabhängiges Textsortenaufkommen und textsortenabhängige Ereignisdarstellung der Reformation in Hamburg 1521-1531, Marburg an der Lahn: Tectum, 2003, p. 95. ISBN 3-8288-8590-X.

- ^ Section «Sonnins Experimente am Turm des Doms», p. 3, on: St. Marien-Dom Hamburg (website of New St. Mary’s Cathedral), retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years, 1830-1910, New York: Penguin, 2005, p. 36. ISBN 0-14-303636-X.

- ^ Section «Abriss des Mariendoms», p. 4, on: St. Marien-Dom Hamburg (website of New St. Mary’s Cathedral), retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Katharina Jeorgakopulos, Hamburgs zerbrochener Dom. Multimediale Rekonstruktion der verlorenen Kirche in Hamburg durch zwei Studentinnen im Studienschwerpunkt Informative Illustration (HAW Hamburg), press release of the Informationsdienst Wissenschaft for the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, 18 October 2006, retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ HARRI (pseudonym of Harald Richert), «Die älteren Kirchenglocken des ehemaligen Amtes Bergedorf», in: Lichtwark-Heft No. 69 (2004), Hamburg: Verlag HB-Werbung, ISSN 1862-3549.

- ^ Joseph Nyary, «Papst-Grab: Stein-Fragment entdeckt», in: Hamburger Abendblatt, 16 August 2005, retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Axel Tiedemann, «Auf dem Domplatz entsteht ein neuer Park», in: Hamburger Abendblatt, 30 January 2008, retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Domplatz eröffnet: Grüner Ruhepol mitten in der Stadt (6 May 2009), press release on behalf of the Behörde für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt (BSU) (Hamburg’s ministry for urban development and environment) archived on: Hamburg.de, retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Die Grafen von Stade und die Erzbischöfe von Bremen-Hamburg vom Ausgang des 10. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 43–104, here p. 95. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ a b Adolf Hofmeister, «Der Kampf um das Erbe der Stader Grafen zwischen den Welfen und der Bremer Kirche (1144–1236)», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 105–157, here p. 123. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ Adolf Hofmeister, «Der Kampf um das Erbe der Stader Grafen zwischen den Welfen und der Bremer Kirche (1144–1236)», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 105–157, here p. 140. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ a b Adolf Hofmeister, «Der Kampf um das Erbe der Stader Grafen zwischen den Welfen und der Bremer Kirche (1144–1236)», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 105–157, here p. 141. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ Michael Schütz, «Die Konsolidierung des Erzstiftes unter Johann Rode», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 263–278, here p. 263. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ a b Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Geschichte der Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Elbe und Weser vom Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II: Mittelalter (1995), pp. 1–21, here p. 6. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ Thies Völker, Die Dithmarscher Landeskirche 1523–1559: Selbständige bauernstaatliche Kirchenorganisation in der Frühneuzeit, section ‘Konfliktauslöser: Besetzung der Pfarrstellen und Klosterprojekt’, posted on 16 July 2009 on: suite101.de: Das Netzwerk der Autoren.

- ^ Thies Völker, Die Dithmarscher Landeskirche 1523–1559: Selbständige bauernstaatliche Kirchenorganisation in der Frühneuzeit, section ‘Gründung der Landeskirche 1523’, posted on 16 July 2009 on: suite101.de: Das Netzwerk der Autoren.

- ^ After violently repelling the first preaching of proponents of the Reformation, slaying Henry of Zutphen [de] in December 1524, Lutheranism nevertheless started to win over Ditmarsians. In 1533 the Council of the 48 turned the Ditmarsian Catholic Church into a Lutheran state church. Cf. Thies Völker, Die Dithmarscher Landeskirche 1523–1559: Selbständige bauernstaatliche Kirchenorganisation in der Frühneuzeit, sections ‘Heinrich von Zütphen 1524’ and ‘Sieg der Reformation 1533’, posted on 16 July 2009 on: suite101.de: Das Netzwerk der Autoren.

- ^ Eitzen became superintendent of the Lutheran Church of the Gottorp share of Holstein and Schleswig (as of 1562), general superintendent of the Lutheran church in the entire Duchies of Holstein and Schleswig (as of 1564).

- ^ Johann Mattheson, Das beschützte Orchestre, oder desselben zweyte Eröffnung: worinn nicht nur e. würcklichen galant-homme, der eben kein Profeßions-Verwandter, sondern auch manchem Musico selbst d. alleraufrichtigste u. deutlichste Vorstellung musicalischer Wissenschaften … ertheilet wird, Hamburg: Schiller, 1717 and 1748, (reprint Leipzig: Zentralantiquariat der DDR, 1981), part I, chapter V, p. 222.

| Hamburg Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of St. Mary’s Sankt Mariendom Dom St. Marien zu Hamburg |

|

St. Mary’s Cathedral |

|

|

Hamburg Cathedral Location within Hamburg Hamburg Cathedral Hamburg Cathedral (Germany) |

|

| 53°32′57″N 09°59′52″E / 53.54917°N 9.99778°ECoordinates: 53°32′57″N 09°59′52″E / 53.54917°N 9.99778°E | |

| Location | Hamburg Old Town |

| Country | Germany |

| Denomination | Lutheran |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic till 1531 |

| History | |

| Status | Proto-cathedral |

| Founded | 831 |

| Founder(s) | Ansgar |

| Dedication | Mary of Nazareth |

| Consecrated | 18 June 1329 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Demolished |

| Architectural type | 5-naved hall church |

| Style | Brick Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1035 |

| Closed | 1531–1540 |

| Demolished | 1804–1807 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | brick |

| Administration | |

| Province | Bremen |

| Archdiocese | Bremen |

Saint Mary’s Cathedral in Hamburg (German: Sankt Mariendom, also Mariendom, or simply Dom or Domkirche, or Hamburger Dom) was the cathedral of the ancient Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hamburg (not to be confused with Hamburg’s modern Archdiocese, est. 1994), which was merged in personal union with the Diocese of Bremen in 847, and later in real union to form the Archdiocese of Hamburg-Bremen, as of 1027.

In 1180 the cathedral compound turned into the cathedral close (German: Domfreiheit; i.e. cathedral immunity district), forming an exclave of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen within the city of Hamburg. By the Reformation the concathedral was converted into a Lutheran church. The cathedral immunity district, since 1648 an exclave of the Duchy of Bremen, was seized by Hamburg in 1803. The city then prompted the demolition of the proto-cathedral between 1804 and 1807.

Location[edit]

The cathedral, in common Italo-Nordic tradition simply called Dom (Italian: Duomo), which is the synecdoche, used – pars pro toto – for most existing or former collegiate churches and cathedrals in Germany alike.[1] The cathedral was situated in the section of the earliest settlement of Hamburg on a geest hill between the rivers Alster and Elbe near Speersort [de] street. Today’s St. Peter’s Church was erected right north of the Dom, today’s Domstraße crosses through the former site of the cathedral. Curienstraße recalls the location of the canons’ courts.

History[edit]

The early history of the Hamburg See and its first cathedral buildings is somewhat obscured. In different struggles on competences and privileges plenty of documents have been completely forged or counterfeited or backdated, in order to corroborate arguments. «These forgeries have drawn a veil before the early history of the [archbishopric of] Hamburg-Bremen.»[2] Results of archeological excavations could not clarify the succession of early cathedral buildings before 1035.

Ansgar, founder of St. Mary’s, copy of a depiction, originally hung in the cathedral, now in St. Peter’s.

A wooden mission church is reported for 831. Pope Gregory IV appointed the Benedictine monk Ansgar as first archbishop as of 834. After the looting of Hamburg and the destruction of the church by Vikings under Horik I in 845 the archdiocese was united with the Diocese of Bremen in 847. Hamburg remained the archiepiscopal seat.

The deposed Pope Benedict V was carried off to Hamburg in 964 and placed under the care of Archbishop Adaldag. He became a deacon then but died in 965 or 966 and was buried in the cathedral.[3] In 983 Prince Mstivoj of the Obodrites destroyed city and church. In 988 Benedict’s remains were presumably transferred to Rome. Archbishop Unwan started reconstructing a fortified cathedral.[4] Under Archbishop Adalbert of Hamburg (1043–1072) Hamburg-Bremen attained its greatest prosperity and later had its deepest troubles. Adalbert was after Hamburg-Bremen’s upgrade to the rank of a Patriarchate of the North and failed completely. Hamburg was even dropped as part of the diocesan name.

With the investiture of Archbishop Liemar the seat definitely moved to Bremen. However, the cathedral chapter of Hamburg persisted with several special rights. Around 1035 Archbishop Adalbrand of Bremen [de] prompted the construction of a first cathedral from brick and his castle.[5] In the same century St. Peter’s Parish Church was established north of the cathedral compound.

However, starting in 1245 Adalbrand’s structure was replaced by a new early Gothic three-naved hall church erected by chapter and Prince-Archbishop Gebhard of Lippe [de], one of the few incumbents of the united see looking for a balanced performance in Bremen and Hamburg, preferring the title Bishop of Hamburg when staying in the diocesan territory right of the Elbe, as is known from seals and documents.[6] Prince-Archbishop Burchard Grelle consecrated the church as archdiocesan concathedral on 18 June 1329.

By the end of the 14th century the concathedral was extended by two more naves. After this, the concathedral remained mostly unchanged until its demolition by 1807. The tower was completed in 1443. In the early 16th century an additional hall, first mentioned as the Nige Gebuwte (Low Saxon for new building) in 1520, was erected closing the adjacent cloister towards the north. This hall was presumably used for sermons, the actual cathedral for masses. The hall was later colloquially called Schappendom after the cupboards (Low Saxon: Schapp[en] [pl.] [de]), which carpenters of Hamburg exhibited there. The traditional fayre at Christmas, recorded for the square in front of the cathedral since the 14th century, and continued as today’s funfayre Hamburger Dom (literally in Hamburg Cathedral), then used to take place within the Schappendom hall.

Starting in 1522 Lutheranism spread among the burghers of Hamburg, gaining their vast majority by 1526, while most canons of the cathedral chapter rather clung to Catholicism, enjoying their extraterritorial status. Hamburg’s Senate (city government) accounted for the new facts and adopted the new denomination in 1528. So when in October 1529, the senate – wielding its advowson – appointed Johannes Aepinus (d. 1553) as Lutheran pastor at the neighbouring St. Peter’s Church, in order to introduce Johannes Bugenhagen’s Lutheran Church Order in the city, Aepinus contested with the prevailingly Catholic cathedral chapter.[7]

St. Mary’s Cathedral in 1800, seen from south against the towers of St. Peter (centre) and St. James (right).

The extraterritorial status and the denominational opposition strengthened the perception of cathedral, chapter, and immunity district as alien element within the city. While almost all inhabitants outside the immunity district had become parishioners of the now Lutheran parish churches, the huge cathedral lacked a congregation. Between the Feast of the Assumption of Mary and December 1529 the city’s militia barred churchgoers from access to the cathedral, given up after imperial protests.[8] Furthermore, the capitular estates in Hamburg and spread all over the North Elbian diocesan area, forming the endowment to maintain canons and cathedral, were increasingly withheld by the respective territorial rulers. Thus in May 1531 the chapter closed the cathedral and its maintenance was neglected.[8]

Meanwhile, the majority of the capitular canons had adopted Lutheranism and elected fellow faithful to eventual vacancies. The cathedral reopened as Lutheran place of worship in 1540. The disputes on capitular estates were regulated by the Bremen Settlement in 1561. The church turned into a Lutheran proto-cathedral and the remaining endowment allowed financing excellent ecclesiastical music, making the proto-cathedral a frequented venue for Lutheran services accompanied by music. The incumbents of the Bremen See used to be themselves Lutherans since the accession of Administrator Henry of Saxe-Lauenburg in 1569. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 transformed the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen, an elective monarchy, into the hereditary monarchy of the Duchy of Bremen, in personal union with Sweden until 1712/15, since 1715 with the House of Hanover. Thus the immunity district turned into a ducal Bremian enclave in the city.

Hamburg Cathedral, seen from east, during demolition in 1806

The architect Ernst Georg Sonnin [de] carried out maintenance works in 1759/1760. Due to the weak, unstable subsoil the cathedral tower was leaning, so Sonnin straightened the tower, as he had done with other church towers in Hamburg, he even demonstrated the gathered public his new technique by reversing it to leaning and again straightening it.[9] Since 1772 the city of Hamburg considered to buy the immunity district, however, not effectuating any changes by then. On the instigation of the ducal Bremian government the cathedral chapter sold its valuable library by the end of the 18th century. Since 1790 the pastorate of the proto-cathedral remained vacant.

By the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss in 1803, the Duchy of Bremen ceded its cathedral immunity districts in Bremen [de] and Hamburg, to these free imperial cities. With the neglect of the proto-cathedral by the ducal government it had dropped out of Hamburg’s cultural life again. Hamburg’s Senate, then holding the ius patronatus to all other Lutheran parish churches had no usage for an additional church, which did not even have the parishioners to maintain it. So in 1802, the Senate, always upholding the city’s vital mercantile interests, ordered Hamburg’s Gothic proto-cathedral to be pulled down, a decision which aroused no serious opposition within the city and which was carried out between 1804 and 1807.

The stones were sold off or used to reinforce the sea defenses along the Elbe; the funerary sculptures and monuments were broken up and used in the reconstruction of the city’s rudimentary sewage system. The Senate was partly motivated by the desire to rid the city of an extraterritorial institution, but it is more than possible that the rise in rents and the high demand for housing at the time also played a role. In any case, the incident was typical of the celebrated Philistinism of the Hamburg authorities. Five more medieval churches in the city were pulled down between 1807 and 1837.[10]

Legacy[edit]

Rescued furnishings[edit]

There was little interest in the valuable furnishings of the proto-cathedral. Few enthusiasts with interest in the history of art did not prevail as to rescuing the building. In order to make the biggest bargain not only the structures above earth have been demolished and sold as construction material but even the grave slabs and most of the fundaments have been dug out to be sold alike. The more than 370 slabs of sandstone have mostly been built in hydraulic structures along the many waterways in Hamburg, broken stones and rubble were used for dikes in Ochsenwerder and Spadenland.[11] So archeological excavations in recent years could not even uncover the exact groundplan.[12]

The rescue of some furnishings we owe to Philipp Otto Runge, prevailing in the merchant republic of Hamburg with the argument, that they could be sold as well. So the Late Gothic cathedral altarpiece, created by Hamburg’s famous artists Absolon Stumme and his stepson Hinrik Bornemann, however, only finished, after their deaths in 1499, by Wilm Dedeke were rescued and sold to East Prussia. In 1946 the altarpiece was nationalised and is now shown in the National Museum, Warsaw.

The congregation of Hamburg’s St. James the Greater Church acquired the St. Luke Altar from the furnishings of the proto-cathedral, now presented in the second southern nave of St. James. Several 15th-century stained glass windows of the apostles were sold to the Catholic congregation of Ludwigslust and are now built in the quire of Ss. Helena and Andrew Church [de], erected 1803–1809.

One of the cathedral bells survived. The Celsa, founded by the bell founder Gerhard van Wou in his workshop on Glockengießerwall in 1487, was bought in 1804 by the Lutheran congregation of St. Nicholas Church [de] in Altengamme, now a part of Hamburg.[13]

Remnants of Pope Benedict V’s cenotaph, which was erected around 1330, but removed in 1782, have been found, besides other findings, in the excavation campaigns (1947–1957, 1980–1987 and 2005–2007).[14]

Hamburger Dom[edit]

A fair held in or in front of the cathedral was first recorded in 1329, at the beginning only at special feasts like Christmas, thus being one of the predecessors of today’s Christmas markets. With the Reformation in the 16th century the fair was also held on other occasions. After the demolition of the cathedral (1804–1807), the fair, still named Hamburger Dom (literally in English: Hamburg Cathedral) moved to Gänsemarkt square (geese market) in 1804, and takes place on Heiligengeistfeld since 1892.

The cathedral site after its demolition[edit]

Former cathedral site with the archeological park and the steel imitations of the walls of the presumable original fortified church, St. Peter’s in the background.

After its demolition the cathedral site remained empty until Carl Ludwig Wimmel and Franz Gustav Forsmann [de] erected a new building between 1838 and 1840 for Hamburg’s most renowned Gymnasium, the Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums. This building was later given to Hamburg’s State and University Library [de], but destroyed in the Allied Bombing Operation Gomorrah in summer 1943. Since the rubble was cleared in 1955 the site remained again empty, crossed by a new thoroughfare named Domstraße (Cathedral Street).

A recent project to rebuild the site with a modern glass steel complex has been dropped after civic protest in 2007. Since 2009 an archeological park covers the site.[15] Steel elements indicate the former walls of the early fortified church supposed to have been the original form of the archiepiscopal see. 39 white benches indicate the likely locations of the former columns of the 5-naved main hall. A single found fundament of one of them can be seen through a glass screen.[16]

Modern Hamburg Cathedral[edit]

In 1994 a new Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hamburg was founded. On this occasion the 1893-erected Catholic St. Mary’s Church in Sankt Georg neighbourhood became the New St. Mary’s Cathedral.

Notable people active at the Dom[edit]

Archbishops, prince-archbishops and administrators[edit]

The incumbents of the Hamburg-Bremen See were usually titled Archbishop of Hamburg and Bishop of Bremen between 848 and 1072, thereafter Hamburg was mostly dropped as titular element, however, some later archbishops continued the tradition of naming both dioceses until 1258. The Lutheran incumbents holding the see since 1569, were officially titled Administrators, but, nevertheless, colloquially referred to as prince-archbishops.

Chapter and canonry[edit]

The cathedral chapter was founded in 834 and its members, the canons (Domherr[en]) enjoyed personal immunity from jurisdiction of the secular local rulers. The chapter wielded the ecclesiastical jurisdiction in the North Elbian part of the archdiocese, to wit Hamburg, Ditmarsh, Holstein, and Stormarn. Thus until the breakthrough of the Reformation the chapter appointed the priests serving in the city’s parishes. Cathedral, chapter and canonry were maintained by numerous prebends comprising urban real estate and feudal dues and soccage collected from dependent farmers in many so-called capitular villages in the afore-mentioned areas. Holsatian aristocracy and Hamburg’s patriciate provided for most of the canons.

At Archbishop Adalgar’s (888–909) instigation Pope Sergius III confirmed the amalgamation of the Diocese of Bremen with the Archdiocese of Hamburg to form the Archdiocese of Hamburg and Bremen, colloquially called Hamburg-Bremen, and by so doing he denied Cologne’s claim as metropolis over Bremen. Sergius prohibited Hamburg’s Chapter to found suffragan dioceses of its own. After the Obodrite destruction of Hamburg in 983 the chapter was dispersed. So Archbishop Unwan appointed a new chapter with twelve canons, with three each taken from Bremen Cathedral chapter, and the three colleges of Bücken, Harsefeld and Ramelsloh.[4] In 1139 Archbishop Adalbero had fled the invasion of Rudolph II, Count of Stade and Frederick II, Count Palatine of Saxony [de], who destroyed Bremen, and established in Hamburg also appointing new capitular canons by 1140.[17]

With the archdiocese gaining princely sovereignty as an imperial estate of the Holy Roman Empire in 1180, the compounds of the Hamburg and Bremen cathedrals with chapterhouses and capitular residential courts (German: Curien) turned into Cathedral Immunity Districts (German: Domfreiheiten), forming exclaves of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen of imperial immediacy. After the Bremen Cathedral chapter, overlooking the three enfranchised Hamburg capitulars, had elected Valdemar of Denmark archbishop in 1207, Bremen’s cathedral dean Burchard of Stumpenhusen, who had opposed this election, fled to Hamburg, then under Danish influence.[18] King Valdemar II of Denmark, in enmity with his father’s cousin Archbishop Valdemar, gained the Hamburg chapter to elect Burchard as anti-archbishop in early 1208. Lacking papal support King Valdemar II himself invested him as Archbishop Burchard I, however, only accepted in North Elbia.[18]

In 1219 the Bremen Chapter again ignored the Hamburg capitulars, fearing their Danish partisanship and elected Gebhard of Lippe [de] archbishop.[19] In 1223 Archbishop Gebhard reconciled the Hamburg chapter and stipulated that three of its capitulars were enfranchised to elect with the Bremen chapter, to wit the provost, presiding the chapter, the dean (Domdechant) and the magister scholarum, in charge of the education at the cathedral school.[20] Pope Honorius III confirmed this settlement in 1224, also affirming the continued existence of both chapters.[20]

Canons were distinguished as younger (canonicus minor) and older (canonicus maior) office holders. The distinction was also evidenced by lower and higher prebends. Johann Rode the Elder served as provost between 1457 and 1460.[21] The known historian Albert Krantz, also serving the city of Hamburg as diplomat, gained a canonicate of the lector primarius in 1493.[22] In 1508 he advanced to Cathedral Dean (Domdechant) of the chapter.[22] Krantz applied himself with zeal to the reform of ecclesiastical abuses, but, though opposed to various corruptions connected with Catholic church discipline, he had little sympathy with the drastic measures of John Wycliffe or Jan Hus. Krantz generally agreed with Martin Luther’s protest against the abuse of indulgences, but refused Luther’s theses on his deathbed in December 1517.

One canonicate, called magister scholarum, was in charge of the education at the cathedral school. 1499 Heinrich Banzkow [de] served as magister scholarum, Johannes Saxonius [de] was appointed magister scholarum in 1550. After the breakthrough of the Reformation canonicates were not necessarily bound to ecclesiastical offices any more, but often served to maintain educators, musicians or scientists.

In 1513 the Ditmarsians founded a Franciscan Friary in Lunden to thank their then national saint patron Mary of Nazareth, fulfilling a vow taken before the Battle of Hemmingstedt in case they could defeat the Dano-Holsatian invaders, however, the Hamburg chapter demanded its say in appointing the prebendaries.[23] After years of dispute, the Council of the 48, the elected governing body of the farmers’ republic of Ditmarsh, decided to found a Gallicanist kind of independent Catholic Church of Ditmarsh in August 1523, denying Hamburg’s capitular jurisdiction in all of Ditmarsh.[24] The chapter could not regain the jurisdiction, including its share in ecclesiastical fees and fines levied in Ditmarsh.[25]

On request of the Senate of Hamburg Luther had sent Bugenhagen to the city. He developed the Lutheran Church Order for Hamburg in 1529. He first aimed at seizing the revenues of concathedral and chapter in favour of the common chest of the urban parishes, financing pastors and teachers. The chapter would be dissolved and the released canons paid a life annuity. However, the then still steadfastly Catholic capitulars refused and were not to be forced due to their immunity and extraterritorial status.

The dispute made many canons leave the city and shut down the concathedral. A lawsuit in the matter was still pendent at the Imperial Chamber Court when after the Smalkaldic War and the subsequent Peace of Augsburg Emperor Ferdinand I brokered the Bremen Settlement in 1561.

Two prebends, privately donated in the 15th century, were reserved for lectors (lector primarius, secundarius) in charge of the advanced theological training of the clergy. After the Reformation the lector primarius was combined with the superintendency of the Lutheran Church of Hamburg, first held by Superintendent Aepinus since 18 May 1532. The lector secundarius was combined with the Lutheran pastorate at the Dom. Smaller prebends were reserved to maintain church musicians and teachers. Known pastors were, among others, Johannes Freder [de] (1540–1547), Paul von Eitzen [de] (as of 1548[26]), and Johann Heinrich Daniel Moldenhawer [de] (1765–1790).

With the Peace of Westphalia the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen had turned from an elective monarchy into the hereditary monarchy of the Duchy of Bremen. While the cathedral chapters of Bremen and Hamburg were not dissolved as such, they sharply lost influence because they used to be the election bodies of the incumbents of the see securing their privileges and endowments by election capitulations, which the incumbents had to issue as self-commitments to the laws and principles established until their accession. Hereditary monarchy opened the gate for absolutism in the Duchy of Bremen. The chapters turned from constitutive legislative bodies into subordinate administrative units receiving orders from the rulers. The last canon officiating as president of the chapter was the jurist Friedrich Johann Lorenz Meyer [de].

Church musicians[edit]

Many church musicians were granted prebends or canonicates, traditionally one canon, titled cantor or precentor, was in charge of preparing and organising musical performances in the Dom. Since the Reformation the Senate of Hamburg furthered the cantorate of the Johanneum surpassing the church music of the Dom. At times both cantorates were held in personal union.

Erasmus Sartorius [de], vicar at the Dom since 1604, was entrusted the cantorate of Johanneum in 1628. Cathedral cantor Thomas Selle officiated between 1642 and 1663. Johann Wolfgang Franck held the cantorate from 1682 to 1685. Friedrich Nicolaus Bruhns, succeeding Nicolaus Adam Strungk in charge of the Hamburger Ratsmusik (Music for the Hamburg Senate) in 1682, became canonicus minor and cathedral cantor in 1687.

Johann Mattheson, diplomat, musician, music theoretician, and cathedral cantor between 1715 and 1728 was the first author to publish on Johann Sebastian Bach.[27] Deafness forced Mattheson to retire. He was succeeded by Reinhard Keiser, who became the cathedral precentor in 1728, and wrote largely church music there until his death in 1739. Between 1756 and 1762 Johann Valentin Görner served as cantor.

Capitular endowment[edit]

The capitular endowment comprised 14 so-called capitular villages (Kapitelsdörfer) outside of then Hamburg, paying dues to the chapter. Following the Reformation the rulers of Holstein seized these villages, legitimised by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. On 18 October 1576 Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp seized a number of capitular endowments against a recurrent annuity paid until 1803.

Endowments:

- The tithe of Ahrensfelde since 1195

- The tithe of Bargfeld since 1195

- Half a hide in Barmbek

- Barmstedt till 1564

- Barsbüttel, grain dues from the village since 1306, all the village since 7 April 1341, till 1576

- Bergstedt [de] since 1345

- Part of Bramfeld since 1271

- The tithe of Duvenstedt since 1255

- Hoisdorf since 1339, till 1576

- Half the tithe of Kirchsteinbek since 1255

- The tithe of Klein Borstel [de] still in 1540

- Meiendorf [de] since 1318

- Two oxgangs in Mellingstedt since 1271

- Domherrenland (canons’ land) in Moorburg [de], till 1803

- An estate in Niendorf since 1343

- Osdorf since the early 14th century

- Half the tithe of Oststeinbek since 1255, the local mill since 1313, till 1576

- Papendorf in Holstein, held by the chapter between 1256 and 1556

- Seven oxgangs and three cottages in Poppenbüttel since 1336, all the village since 1389

- Dues from Rahlstedt since 1296

- Rellingen till 1564

- The tithe of Rissen since 1255

- Stemwarde part of its forest in 1259, all the village since 22 June 1263, till 1576

- A recurrent rent from Stockelsdorf manor since 1358

- Todendorf since 1263

- Willinghusen half the village since 1238, all the village since 1342, till 1576

- Wulfsdorf

- Wulksfelde

References[edit]

- Ralf Busch, Hamburg Altstadt, Stuttgart: Theiss, 2002, (=Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Deutschland; vol. 41).

- Adolf Hofmeister, «Der Kampf um das Erbe der Stader Grafen zwischen den Welfen und der Bremer Kirche (1144–1236)», in: Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser: 3 vols., Hans-Eckhard Dannenberg and Heinz-Joachim Schulze (eds.) on behalf of the Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 1995 and 2008, vol. I ‘Vor- und Frühgeschichte’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5), vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2), vol. III ‘Neuzeit’ (2008; ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9), (=Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden; vols. 7–9), vol. II: pp. 105–157.

- Kai Mathieu, Der Hamburger Dom, Untersuchungen zur Baugeschichte im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert (1245–1329) und eine Dokumentation zum Abbruch in den Jahren 1804 – 1807, Hamburg: Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte, 1973.

- Friedrich Johann Lorenz Meyer, Blick in die Domkirche in Hamburg, Hamburg: Nestler, 1804.

- Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Die Grafen von Stade und die Erzbischöfe von Bremen-Hamburg vom Ausgang des 10. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts», in: Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser: 3 vols., Hans-Eckhard Dannenberg and Heinz-Joachim Schulze (eds.) on behalf of the Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 1995 and 2008, vol. I ‘Vor- und Frühgeschichte’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5), vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2), vol. III ‘Neuzeit’ (2008; ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9), (=Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden; vols. 7–9), vol. II: pp. 43–104.

- Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Geschichte der Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Elbe und Weser vom Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts», in: Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser: 3 vols., Hans-Eckhard Dannenberg and Heinz-Joachim Schulze (eds.) on behalf of the Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 1995 and 2008, vol. I ‘Vor- und Frühgeschichte’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5), vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2), vol. III ‘Neuzeit’ (2008; ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9), (=Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden; vols. 7–9), vol. II: pp. 1–21.

- Michael Schütz, «Die Konsolidierung des Erzstiftes unter Johann Rode», in: Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser: 3 vols., Hans-Eckhard Dannenberg and Heinz-Joachim Schulze (eds.), Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 1995 and 2008, vol. I ‘Vor- und Frühgeschichte’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5), vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’ (1995; ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2), vol. III ‘Neuzeit’ (2008; ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9), (=Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden; vols. 7–9), vol. II: pp. 263–278.

- Ferdinand Stöter, Die ehemalige St. Marien Kirche oder der Dom zu Hamburg in Bildern mit erläuternden Texten von F. Stöter, Hamburg: Gräfe, 1879.

External links[edit]

- Daten zur Geschichte des Hamburger Mariendoms

Notes[edit]

- ^ Therefore the uniform translation of these terms into English as cathedrals may not always be appropriate.

- ^ The original quotation: «Diese Fälschungen haben einen Schleier vor die Frühgeschichte Hamburg-Bremens gezogen.» Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Geschichte der Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Elbe und Weser vom Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II: Mittelalter (1995), pp. 1–21, here p. 6. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2. Addition in edged brackets not in the original.

- ^ Erich Verg and Martin Verg, Das Abenteuer, das Hamburg heißt, Hamburg: Ellert & Richter, 42007, p. 15. ISBN 978-3-8319-0137-1.

- ^ a b Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Die Grafen von Stade und die Erzbischöfe von Bremen-Hamburg vom Ausgang des 10. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 43–104, here p. 53. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Die Grafen von Stade und die Erzbischöfe von Bremen-Hamburg vom Ausgang des 10. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 43–104, here p. 54. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ However, he already accounted for the reversion of the original ranking using left of the river Elbe the title Archbishop of Bremen.

- ^ This contest gave rise to his Ioannis Hepini Pinacidion de Romanæ ecclesiæ imposturis et Papisticis sutelis/ aduersus impudentem Hamburgensium Canonicorum autonomiam, Hamburg: Georg Richolff the Younger, 1530.

- ^ a b Jana Jürgs, Der Reformationsdiskurs der Stadt Hamburg: Ereignisabhängiges Textsortenaufkommen und textsortenabhängige Ereignisdarstellung der Reformation in Hamburg 1521-1531, Marburg an der Lahn: Tectum, 2003, p. 95. ISBN 3-8288-8590-X.

- ^ Section «Sonnins Experimente am Turm des Doms», p. 3, on: St. Marien-Dom Hamburg (website of New St. Mary’s Cathedral), retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years, 1830-1910, New York: Penguin, 2005, p. 36. ISBN 0-14-303636-X.

- ^ Section «Abriss des Mariendoms», p. 4, on: St. Marien-Dom Hamburg (website of New St. Mary’s Cathedral), retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Katharina Jeorgakopulos, Hamburgs zerbrochener Dom. Multimediale Rekonstruktion der verlorenen Kirche in Hamburg durch zwei Studentinnen im Studienschwerpunkt Informative Illustration (HAW Hamburg), press release of the Informationsdienst Wissenschaft for the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, 18 October 2006, retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ HARRI (pseudonym of Harald Richert), «Die älteren Kirchenglocken des ehemaligen Amtes Bergedorf», in: Lichtwark-Heft No. 69 (2004), Hamburg: Verlag HB-Werbung, ISSN 1862-3549.

- ^ Joseph Nyary, «Papst-Grab: Stein-Fragment entdeckt», in: Hamburger Abendblatt, 16 August 2005, retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Axel Tiedemann, «Auf dem Domplatz entsteht ein neuer Park», in: Hamburger Abendblatt, 30 January 2008, retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Domplatz eröffnet: Grüner Ruhepol mitten in der Stadt (6 May 2009), press release on behalf of the Behörde für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt (BSU) (Hamburg’s ministry for urban development and environment) archived on: Hamburg.de, retrieved on 21 June 2011.

- ^ Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Die Grafen von Stade und die Erzbischöfe von Bremen-Hamburg vom Ausgang des 10. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 43–104, here p. 95. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ a b Adolf Hofmeister, «Der Kampf um das Erbe der Stader Grafen zwischen den Welfen und der Bremer Kirche (1144–1236)», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 105–157, here p. 123. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ Adolf Hofmeister, «Der Kampf um das Erbe der Stader Grafen zwischen den Welfen und der Bremer Kirche (1144–1236)», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 105–157, here p. 140. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ a b Adolf Hofmeister, «Der Kampf um das Erbe der Stader Grafen zwischen den Welfen und der Bremer Kirche (1144–1236)», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 105–157, here p. 141. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ Michael Schütz, «Die Konsolidierung des Erzstiftes unter Johann Rode», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II ‘Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte)’: pp. 263–278, here p. 263. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ a b Heinz-Joachim Schulze, «Geschichte der Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Elbe und Weser vom Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts», in: see references for bibliographical details, vol. II: Mittelalter (1995), pp. 1–21, here p. 6. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

- ^ Thies Völker, Die Dithmarscher Landeskirche 1523–1559: Selbständige bauernstaatliche Kirchenorganisation in der Frühneuzeit, section ‘Konfliktauslöser: Besetzung der Pfarrstellen und Klosterprojekt’, posted on 16 July 2009 on: suite101.de: Das Netzwerk der Autoren.

- ^ Thies Völker, Die Dithmarscher Landeskirche 1523–1559: Selbständige bauernstaatliche Kirchenorganisation in der Frühneuzeit, section ‘Gründung der Landeskirche 1523’, posted on 16 July 2009 on: suite101.de: Das Netzwerk der Autoren.

- ^ After violently repelling the first preaching of proponents of the Reformation, slaying Henry of Zutphen [de] in December 1524, Lutheranism nevertheless started to win over Ditmarsians. In 1533 the Council of the 48 turned the Ditmarsian Catholic Church into a Lutheran state church. Cf. Thies Völker, Die Dithmarscher Landeskirche 1523–1559: Selbständige bauernstaatliche Kirchenorganisation in der Frühneuzeit, sections ‘Heinrich von Zütphen 1524’ and ‘Sieg der Reformation 1533’, posted on 16 July 2009 on: suite101.de: Das Netzwerk der Autoren.