Christmas tree decorated with ribbons, stars and glass balls

Family decorating Christmas tree (c. 1970s)

A Christmas tree is a decorated tree, usually an evergreen conifer, such as a spruce, pine or fir, or an artificial tree of similar appearance, associated with the celebration of Christmas.[1] The custom was further developed in early modern Germany where German Protestant Christians brought decorated trees into their homes.[2][3] It acquired popularity beyond the Lutheran areas of Germany[2][4] and the Baltic governorates during the second half of the 19th century, at first among the upper classes.

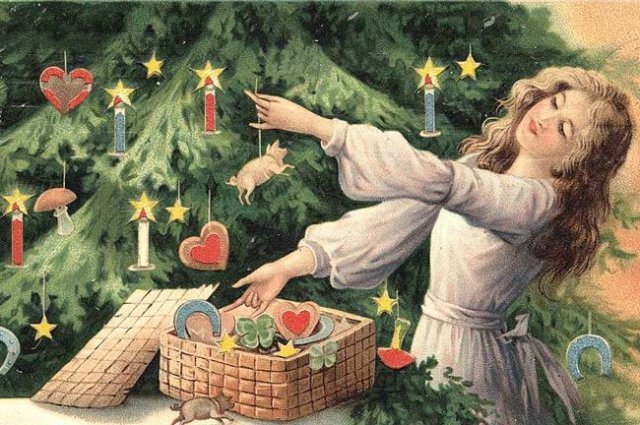

The tree was traditionally decorated with «roses made of colored paper, apples, wafers, tinsel, [and] sweetmeats».[2] Moravian Christians began to illuminate Christmas trees with candles,[5] which were often replaced by Christmas lights after the advent of electrification.[6] Today, there is a wide variety of traditional and modern ornaments, such as garlands, baubles, tinsel, and candy canes. An angel or star might be placed at the top of the tree to represent the Angel Gabriel or the Star of Bethlehem, respectively, from the Nativity.[7][8] Edible items such as gingerbread, chocolate, and other sweets are also popular and are tied to or hung from the tree’s branches with ribbons. The Christmas tree has been historically regarded as a custom of the Lutheran Churches and only in 1982 did the Catholic Church erect the Vatican Christmas Tree.[9]

In the Western Christian tradition, Christmas trees are variously erected on days such as the first day of Advent or even as late as Christmas Eve depending on the country;[10] customs of the same faith hold that the two traditional days when Christmas decorations, such as the Christmas tree, are removed are Twelfth Night and, if they are not taken down on that day, Candlemas, the latter of which ends the Christmas-Epiphany season in some denominations.[10][11]

The Christmas tree is sometimes compared with the «Yule-tree», especially in discussions of its folkloric origins.[12][13][14]

History[edit]

Origin of the modern Christmas tree[edit]

Martin Luther is depicted with his family and friends in front of a Christmas tree on Christmas Eve

Modern Christmas trees originated during the Renaissance in early modern Germany. Its 16th-century origins are sometimes associated with Protestant Christian reformer Martin Luther, who is said to have first added lighted candles to an evergreen tree.[15][16][17] The Christmas tree was first recorded to be used by German Lutherans in the 16th century, with records indicating that a Christmas tree was placed in the Cathedral of Strasbourg in 1539, under the leadership of the Protestant Reformer, Martin Bucer.[18][19] The Moravian Christians put lighted candles on those trees.»[5][20] The earliest known firmly dated representation of a Christmas tree is on the keystone sculpture of a private home in Turckheim, Alsace (then part of Germany, today France), with the date 1576.[21]

Possible predecessors[edit]

Modern Christmas trees have been related to the «tree of paradise» of medieval mystery plays that were given on 24 December, the commemoration and name day of Adam and Eve in various countries. In such plays, a tree decorated with apples (representing fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and thus to the original sin that Christ took away) and round white wafers (to represent the Eucharist and redemption) was used as a setting for the play.[6] Like the Christmas crib, the Paradise tree was later placed in homes. The apples were replaced by round objects such as shiny red balls.[13][14][22][23][24][25]

At the end of the Middle Ages, an early predecessor appears referred in the 15th century Regiment of the Cistercian Alcobaça Monastery in Portugal. The Regiment of the local high-Sacristans of the Cistercian Order refers to what may be considered the oldest references to the Christmas tree: «Note on how to put the Christmas branch, scilicet: On the Christmas eve, you will look for a large Branch of green laurel, and you shall reap many red oranges, and place them on the branches that come of the laurel, specifically as you have seen, and in every orange you shall put a candle, and hang the Branch by a rope in the pole, which shall be by the candle of the high altar.»[26]

Yggdrasil, in Norse cosmology, is an immense and central sacred tree.

Other sources have offered a connection between the symbolism of the first documented Christmas trees in Germany around 1600 and the trees of pre-Christian traditions, though this claim has been disputed.[27] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, «The use of evergreen trees, wreaths, and garlands to symbolize eternal life was a custom of the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, and Hebrews. Tree worship was common among the pagan Europeans and survived their conversion to Christianity in the Scandinavian customs of decorating the house and barn with evergreens at the New Year to scare away the devil and of setting up a tree for the birds during Christmas time.»[28]

During the Roman mid-winter festival of Saturnalia, houses were decorated with wreaths of evergreen plants and these customs were adopted into the Christian celebration of Christmas.[29] In the poem Epithalamium by Catullus, he tells of the gods decorating the home of Peleus with trees, including laurel and cypress. Later Libanius, Tertullian, and Chrysostom speak of the use of evergreen trees to adorn Christian houses.[30]

The Vikings and Saxons worshiped trees.[29] The story of Saint Boniface cutting down Donar’s Oak illustrates the pagan practices in 8th century among the Germans. A later folk version of the story adds the detail that an evergreen tree grew in place of the felled oak, telling them about how its triangular shape reminds humanity of the Trinity and how it points to heaven.[31][a]

Historical practices by region[edit]

Estonia, Latvia, and Germany[edit]

Customs of erecting decorated trees in winter time can be traced to Christmas celebrations in Renaissance-era guilds in Northern Germany and Livonia. The first evidence of decorated trees associated with Christmas Day are trees in guildhalls decorated with sweets to be enjoyed by the apprentices and children. In Livonia (present-day Estonia and Latvia), in 1441, 1442, 1510, and 1514, the Brotherhood of Blackheads erected a tree for the holidays in their guild houses in Reval (now Tallinn) and Riga. On the last night of the celebrations leading up to the holidays, the tree was taken to the Town Hall Square, where the members of the brotherhood danced around it.[32]

A Bremen guild chronicle of 1570 reports that a small tree decorated with «apples, nuts, dates, pretzels, and paper flowers» was erected in the guild-house for the benefit of the guild members’ children, who collected the dainties on Christmas Day.[33] In 1584, the pastor and chronicler Balthasar Russow in his Chronica der Provinz Lyfflandt (1584) wrote of an established tradition of setting up a decorated spruce at the market square, where the young men «went with a flock of maidens and women, first sang and danced there and then set the tree aflame».

After the Protestant Reformation, such trees are seen in the houses of upper-class Protestant families as a counterpart to the Catholic Christmas cribs. This transition from the guild hall to the bourgeois family homes in the Protestant parts of Germany ultimately gives rise to the modern tradition as it developed in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the present-day, the churches and homes of Protestants and Catholics feature both Christmas cribs and Christmas trees.[34]

Poland[edit]

The hanging of a podłaźniczka during Christmastide is an old Polish folk custom

In Poland, there is a folk tradition dating back to an old Slavic pre-Christian custom of suspending a branch of fir, spruce, or pine from the ceiling rafters, called podłaźniczka, during the time of the Koliada winter festival.[35] The branches were decorated with apples, nuts, acorns, and stars made of straw. In more recent times, the decorations also included colored paper cutouts (wycinanki), wafers, cookies, and Christmas baubles. According to old pagan beliefs, the branch’s powers were linked to good harvest and prosperity.[36]

The custom was practiced by the peasants until the early 20th century, particularly in the regions of Lesser Poland and Upper Silesia.[37] Most often the branches were hung above the wigilia dinner table on Christmas Eve. Beginning in the mid-19th century, the tradition over time was almost completely replaced by the later German practice of decorating a standing Christmas tree.[38]

18th to early 20th centuries[edit]

Adoption by European nobility[edit]

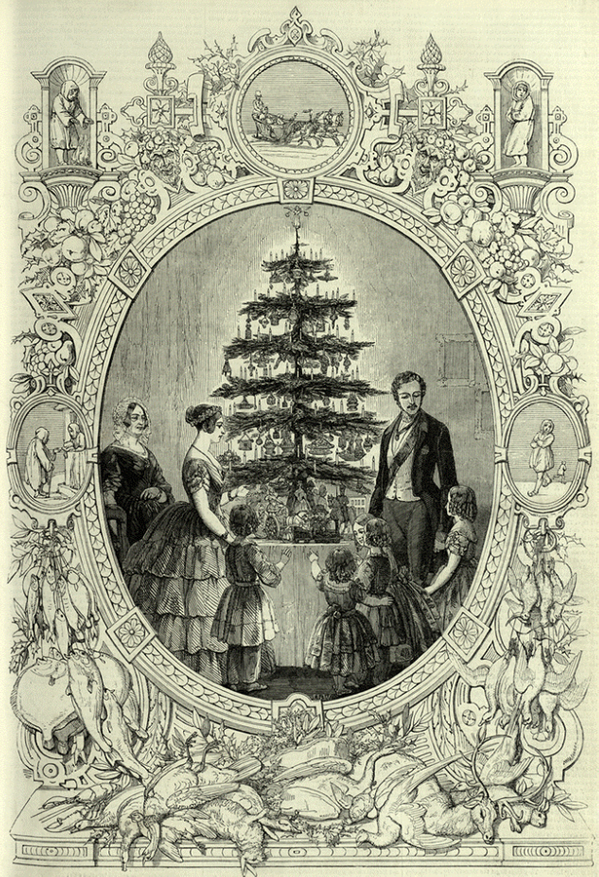

German Christmas tree, book illustration (1888)

In the early 19th century, the custom became popular among the nobility and spread to royal courts as far as Russia. Introduced by Fanny von Arnstein and popularized by Princess Henrietta of Nassau-Weilburg the Christmas tree reached Vienna in 1814 during the Congress of Vienna, and the custom spread across Austria in the following years.[39] In France, the first Christmas tree was introduced in 1840 by the duchesse d’Orléans. In Denmark a Danish newspaper claims that the first attested Christmas tree was lit in 1808 by countess Wilhemine of Holsteinborg. It was the aging countess who told the story of the first Danish Christmas tree to the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen in 1865. He had published a fairy tale called The Fir-Tree in 1844, recounting the fate of a fir tree being used as a Christmas tree.[40]

Adoption by country or region[edit]

Germany[edit]

A German Christmas tree in a room at Versailles turned into a military hospital

By the early 18th century, the custom had become common in towns of the upper Rhineland, but it had not yet spread to rural areas. Wax candles, expensive items at the time, are found in attestations from the late 18th century.

Along the lower Rhine, an area of Roman Catholic majority, the Christmas tree was largely regarded as a Protestant custom. As a result, it remained confined to the upper Rhineland for a relatively long period of time. The custom did eventually gain wider acceptance beginning around 1815 by way of Prussian officials who emigrated there following the Congress of Vienna.

In the 19th century, the Christmas tree was taken to be an expression of German culture and of Gemütlichkeit, especially among emigrants overseas.[41]

A decisive factor in winning general popularity was the German army’s decision to place Christmas trees in its barracks and military hospitals during the Franco-Prussian War. Only at the start of the 20th century did Christmas trees appear inside churches, this time in a new brightly lit form.[42]

Slovenia[edit]

Early Slovenian custom dating back to around the 17th century was to suspend the tree either upright or upside-down above the well, a corner of the dinner table, in the backyard, or from the fences, modestly decorated with fruits or not decorated at all. German brewer Peter Luelsdorf brought the first Christmas tree of the current tradition to Slovenia in 1845. He set it up in his small brewery inn in Ljubljana, the Slovenian capital. German officials, craftsmen and merchants quickly spread the tradition among the bourgeois population. The trees were typically decorated with walnuts, golden apples, carobs, and candles. At first the Catholic majority rejected this custom because they considered it a typical Protestant tradition. The first decorated Christmas Market was organized in Ljubljana already in 1859. However, this tradition was almost unknown to the rural population until World War I, after which everyone started decorating trees. Spruce trees have a centuries-long tradition in Slovenia. After World War II during Yugoslavia period, trees set in the public places (towns, squares, and markets) were politically replaced with fir trees, a symbol of socialism and Slavic mythology strongly associated with loyalty, courage, and dignity. However, spruce retained its popularity in Slovenian homes during those years and came back to public places after independence.[43][44][45][46]

Britain[edit]

Although the tradition of decorating churches and homes with evergreens at Christmas was long established,[48] the custom of decorating an entire small tree was unknown in Britain until some two centuries ago. The German-born Queen Charlotte introduced a Christmas tree at a party she gave for children in 1800.[49] The custom did not at first spread much beyond the royal family.[b] Queen Victoria as a child was familiar with it and a tree was placed in her room every Christmas. In her journal for Christmas Eve 1832, the delighted 13-year-old princess wrote:[51]

After dinner […] we then went into the drawing room near the dining room […] There were two large round tables on which were placed two trees hung with lights and sugar ornaments. All the presents being placed round the trees […]

After Victoria’s marriage to her German cousin Prince Albert, by 1841 the custom became even more widespread[52] as wealthier middle-class families followed the fashion. In 1842 a newspaper advert for Christmas trees makes clear their smart cachet, German origins and association with children and gift-giving.[53] An illustrated book, The Christmas Tree, describing their use and origins in detail, was on sale in December 1844.[54] On 2 January 1846 Elizabeth Fielding (née Fox Strangways) wrote from Lacock Abbey to William Henry Fox-Talbot: «Constance is extremely busy preparing the Bohemian Xmas Tree. It is made from Caroline’s[55] description of those she saw in Germany».[56] In 1847 Prince Albert wrote: «I must now seek in the children an echo of what Ernest [his brother] and I were in the old time, of what we felt and thought; and their delight in the Christmas trees is not less than ours used to be».[57] A boost to the trend was given in 1848[58] when The Illustrated London News,[59] in a report picked up by other papers,[60] described the trees in Windsor Castle in detail and showed the main tree, surrounded by the royal family, on its cover. In fewer than ten years their use in better-off homes was widespread. By 1856 a northern provincial newspaper contained an advert alluding casually to them,[61] as well as reporting the accidental death of a woman whose dress caught fire as she lit the tapers on a Christmas tree.[62] They had not yet spread down the social scale though, as a report from Berlin in 1858 contrasts the situation there where «Every family has its own» with that of Britain, where Christmas trees were still the preserve of the wealthy or the «romantic».[63]

Their use at public entertainments, charity bazaars and in hospitals made them increasingly familiar however, and in 1906 a charity was set up specifically to ensure even poor children in London slums «who had never seen a Christmas tree» would enjoy one that year.[64] Anti-German sentiment after World War I briefly reduced their popularity[65] but the effect was short-lived,[66] and by the mid-1920s the use of Christmas trees had spread to all classes.[67] In 1933 a restriction on the importation of foreign trees led to the «rapid growth of a new industry» as the growing of Christmas trees within Britain became commercially viable due to the size of demand.[68] By 2013 the number of trees grown in Britain for the Christmas market was approximately eight million[69] and their display in homes, shops and public spaces a normal part of the Christmas season.

Georgia[edit]

Georgians have their own traditional Christmas tree called Chichilaki, made from dried up hazelnut or walnut branches that are shaped to form a small coniferous tree.[70] These pale-colored ornaments differ in height from 20 cm (7.9 in) to 3 meters (9.8 ft). Chichilakis are most common in the Guria and Samegrelo regions of Georgia near the Black Sea, but they can also be found in some stores around the capital of Tbilisi.[71]

Georgians believe that Chichilaki resembles the famous beard of St. Basil the Great, because Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates St. Basil on 1 January.

The Bahamas[edit]

The earliest reference of Christmas trees being used in The Bahamas dates to January 1864 and is associated with the Anglican Sunday Schools in Nassau, New Providence: «After prayers and a sermon from the Rev. R. Swann, the teachers and children of St. Agnes’, accompanied by those of St. Mary’s, marched to the Parsonage of Rev. J. H. Fisher, in front of which a large Christmas tree had been planted for their gratification. The delighted little ones formed a circle around it singing «Come follow me to the Christmas tree».»[72] The gifts decorated the trees as ornaments and the children were given tickets with numbers that matched the gifts. This appears to be the typical way of decorating the trees in the 1860s Bahamas. In the Christmas of 1864, there was a Christmas tree put up in the Ladies Saloon in the Royal Victoria Hotel for the respectable children of the neighbourhood. The tree was ornamented with gifts for the children who formed a circle about it and sung the song «Oats and Beans». The gifts were later given to the children in the name of Santa Claus.[73]

North America[edit]

General and Mrs. Riedesel celebrating Christmas.

The tradition was introduced to North America in the winter of 1781 by Hessian soldiers stationed in the Province of Québec (1763–1791) to garrison the colony against American attack. General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel and his wife, the Baroness von Riedesel, held a Christmas party for the officers at Sorel, Quebec, delighting their guests with a fir tree decorated with candles and fruits.[74]

The Christmas tree became very common in the United States of America in the early nineteenth century. Dating from late 1812 or early 1813, the watercolor sketchbooks of John Lewis Krimmel contain perhaps the earliest depictions of a Christmas tree in American art, representing a family celebrating Christmas Eve in the Moravian tradition.[75] The first published image of a Christmas tree appeared in 1836 as the frontispiece to The Stranger’s Gift by Hermann Bokum. The first mention of the Christmas tree in American literature was in a story in the 1836 edition of The Token and Atlantic Souvenir, titled «New Year’s Day», by Catherine Maria Sedgwick, where she tells the story of a German maid decorating her mistress’s tree. Also, a woodcut of the British royal family with their Christmas tree at Windsor Castle, initially published in The Illustrated London News December 1848, was copied in the United States at Christmas 1850, in Godey’s Lady’s Book. Godey’s copied it exactly, except for the removal of the Queen’s tiara and Prince Albert’s moustache, to remake the engraving into an American scene.[76] The republished Godey’s image became the first widely circulated picture of a decorated evergreen Christmas tree in America. Art historian Karal Ann Marling called Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, shorn of their royal trappings, «the first influential American Christmas tree».[77] Folk-culture historian Alfred Lewis Shoemaker states, «In all of America there was no more important medium in spreading the Christmas tree in the decade 1850–60 than Godey’s Lady’s Book«. The image was reprinted in 1860, and by the 1870s, putting up a Christmas tree had become even more common in America.[76]

Drawing depicting family with their Christmas tree in 1809.

President Benjamin Harrison and his wife Caroline put up the first White House Christmas tree in 1889.[78]

Several cities in the United States with German connections lay claim to that country’s first Christmas tree: Windsor Locks, Connecticut, claims that a Hessian soldier put up a Christmas tree in 1777 while imprisoned at the Noden-Reed House,[79] while the «First Christmas Tree in America» is also claimed by Easton, Pennsylvania, where German settlers purportedly erected a Christmas tree in 1816. In his diary, Matthew Zahm of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, recorded the use of a Christmas tree in 1821, leading Lancaster to also lay claim to the first Christmas tree in America.[80] Other accounts credit Charles Follen, a German immigrant to Boston, for being the first to introduce to America the custom of decorating a Christmas tree.[81] August Imgard, a German immigrant living in Wooster, Ohio, is said to be the first to popularize the practice of decorating a tree with candy canes.[citation needed] In 1847, Imgard cut a blue spruce tree from a woods outside town, had the Wooster village tinsmith construct a star, and placed the tree in his house, decorating it with paper ornaments, gilded nuts and Kuchen.[82] German immigrant Charles Minnigerode accepted a position as a professor of humanities at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1842, where he taught Latin and Greek. Entering into the social life of the Virginia Tidewater, Minnigerode introduced the German custom of decorating an evergreen tree at Christmas at the home of law professor St. George Tucker, thereby becoming another of many influences that prompted Americans to adopt the practice at about that time.[83] An 1853 article on Christmas customs in Pennsylvania defines them as mostly «German in origin», including the Christmas tree, which is «planted in a flower pot filled with earth, and its branches are covered with presents, chiefly of confectionary, for the younger members of the family.» The article distinguishes between customs in different states however, claiming that in New England generally «Christmas is not much celebrated», whereas in Pennsylvania and New York it is.[84]

When Edward H. Johnson was vice president of the Edison Electric Light Company, a predecessor of Con Edison, he created the first known electrically illuminated Christmas tree at his home in New York City in 1882. Johnson became the «Father of Electric Christmas Tree Lights».[85]

The lyrics sung in the United States to the German tune O Tannenbaum begin «O Christmas tree…», giving rise to the mistaken idea that the German word Tannenbaum (fir tree) means «Christmas tree», the German word for which is instead Weihnachtsbaum.

-

Copy of an 1848 engraving of the British royal family with their tree, modified and widely published in American magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1850.

-

First published image of a Christmas tree, frontispiece to Hermann Bokum’s 1836 The Stranger’s Gift

-

The Christmas tree by Winslow Homer, 1858

-

Christmas in the Netherlands, c. 1899

-

Christmas tree depicted as Christmas card by Prang & Co. (Boston) 1880

-

-

An Italian-American family on Christmas, 1924

1935 to present[edit]

Under the state atheism of the Soviet Union, the Christmas tree, along with the entire celebration of the Christian holiday, was banned in that country after the October Revolution. However, the government then introduced a New-year spruce (Russian: Новогодняя ёлка, romanized: Novogodnyaya yolka) in 1935 for the New Year holiday.[86][87][88] It became a fully secular icon of the New Year holiday: for example, the crowning star was regarded not as a symbol of Bethlehem Star, but as the Red star. Decorations, such as figurines of airplanes, bicycles, space rockets, cosmonauts, and characters of Russian fairy tales, were produced. This tradition persists after the fall of the USSR, with the New Year holiday outweighing the Christmas (7 January) for a wide majority of Russian people.[89]

The Peanuts TV special A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965) was influential on the pop culture surrounding the Christmas tree. Aluminum Christmas trees were popular during the early 1960s in the US. They were satirized in the TV special and came to be seen as symbolizing the commercialization of Christmas. The term Charlie Brown Christmas tree, describing any poor-looking or malformed little tree, also derives from the 1965 TV special, based on the appearance of Charlie Brown’s Christmas tree.[90]

- 1935 to present

-

A Christmas tree from 1951, in a home in New York state

-

Christmas tree with presents

-

Christmas Tree in the cozy room at the Wisconsin Governor’s mansion.

-

A Soviet-era (1960s) New Year tree decoration depicting a cosmonaut

-

Christmas Trees in church

-

A chrismon tree (St. Alban’s Anglican Cathedral, Oviedo, Florida)

Public Christmas trees[edit]

An early example of public Christmas tree for the children of unemployed parents in Prague (Czech Republic), 1931

Since the early 20th century, it has become common in many cities, towns, and department stores to put up public Christmas trees outdoors, such as the Macy’s Great Tree in Atlanta (since 1948), the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree in New York City, and the large Christmas tree at Victoria Square in Adelaide.

The use of fire retardant allows many indoor public areas to place real trees and be compliant with code. Licensed applicants of fire retardant solution spray the tree, tag the tree, and provide a certificate for inspection.

The United States’ National Christmas Tree has been lit each year since 1923 on the South Lawn of the White House, becoming part of what evolved into a major holiday event at the White House. President Jimmy Carter lit only the crowning star atop the tree in 1979 in honor of the Americans being held hostage in Iran.[91] The same was true in 1980, except the tree was fully lit for 417 seconds, one second for each day the hostages had been in captivity.[91]

During most of the 1970s and 1980s, the largest decorated Christmas tree in the world was put up every year on the property of the National Enquirer in Lantana, Florida. This tradition grew into one of the most spectacular and celebrated events in the history of southern Florida, but was discontinued on the death of the paper’s founder in the late 1980s.[92]

In some cities, a charity event called the Festival of Trees is organized, in which multiple trees are decorated and displayed.

The giving of Christmas trees has also often been associated with the end of hostilities. After the signing of the Armistice in 1918 the city of Manchester sent a tree, and £500 to buy chocolate and cakes, for the children of the much-bombarded town of Lille in northern France.[93] In some cases the trees represent special commemorative gifts, such as in Trafalgar Square in London, where the City of Oslo, Norway presents a tree to the people of London as a token of appreciation for the British support of Norwegian resistance during the Second World War; in Boston, where the tree is a gift from the province of Nova Scotia, in thanks for rapid deployment of supplies and rescuers to the 1917 ammunition ship explosion that leveled the city of Halifax; and in Newcastle upon Tyne, where the main civic Christmas tree is an annual gift from the city of Bergen, in thanks for the part played by soldiers from Newcastle in liberating Bergen from Nazi occupation.[94] Norway also annually gifts a Christmas tree to Washington, D.C. as a symbol of friendship between Norway and the US and as an expression of gratitude from Norway for the help received from the US during World War II.[95]

- Public Christmas trees

-

Christmas tree in Salerno old town, Italy.

-

-

-

-

Christmas tree and Metropolitan Cathedral at Mexico City’s zócalo.

-

Lisbon, Portugal, 75 metres (246 feet) Christmas tree.

-

An illuminated Christmas tree in Madrid.

-

Christmas trees in Ocean Terminal, Harbour City, Hong Kong

-

Christmas tree in Lugano, Switzerland.

Customs and traditions[edit]

Setting up and taking down[edit]

Adding decorations to tree

Both setting up and taking down a Christmas tree are associated with specific dates; liturgically, this is done through the hanging of the greens ceremony.[96] In many areas, it has become customary to set up one’s Christmas tree on Advent Sunday, the first day of the Advent season.[97][98] Traditionally, however, Christmas trees were not brought in and decorated until the evening of Christmas Eve (24 December), the end of the Advent season and the start of the twelve days of Christmastide.[99] It is customary for Christians in many localities to remove their Christmas decorations on the last day of the twelve days of Christmastide that falls on 5 January—Epiphany Eve (Twelfth Night),[100] although those in other Christian countries remove them on Candlemas, the conclusion of the extended Christmas-Epiphany season (Epiphanytide).[101][102] According to the first tradition, those who fail to remember to remove their Christmas decorations on Epiphany Eve must leave them untouched until Candlemas, the second opportunity to remove them; failure to observe this custom is considered inauspicious.[103][104]

Decorations[edit]

Christmas ornaments are decorations (usually made of glass, metal, wood, or ceramics) that are used to decorate a Christmas tree. The first decorated trees were adorned with apples, white candy canes and pastries in the shapes of stars, hearts and flowers. Glass baubles were first made in Lauscha, Germany, and also garlands of glass beads and tin figures that could be hung on trees. The popularity of these decorations fueled the production of glass figures made by highly skilled artisans with clay molds.

Tinsel and several types of garland or ribbon are commonly used as Christmas tree decorations. Silvered saran-based tinsel was introduced later. Delicate mold-blown and painted colored glass Christmas ornaments were a specialty of the glass factories in the Thuringian Forest, especially in Lauscha in the late 19th century, and have since become a large industry, complete with famous-name designers. Baubles are another common decoration, consisting of small hollow glass or plastic spheres coated with a thin metallic layer to make them reflective, with a further coating of a thin pigmented polymer in order to provide coloration.

Lighting with electric lights (Christmas lights or, in the United Kingdom, fairy lights) is commonly done. A tree-topper, sometimes an angel but more frequently a star, completes the decoration.

In the late 1800s, home-made white Christmas trees were made by wrapping strips of cotton batting around leafless branches creating the appearance of a snow-laden tree.

In the 1940s and 1950s, popularized by Hollywood films in the late 1930s, flocking was very popular on the West Coast of the United States. There were home flocking kits that could be used with vacuum cleaners. In the 1980s some trees were sprayed with fluffy white flocking to simulate snow.

- Types of ornaments

-

Golden glass ball/bauble

-

Snowman/baseball novelty ornament

-

Toy bear decoration

-

Egg shaped glass ornament

-

Cloth cotton batting ornament

-

Imitation tree snow

-

Straw ornaments

-

-

Swaddled babies, 1850–1899

-

Paper maché ornament

-

Faceted indented glass ornament

-

Ceramic ornament

-

-

Glass icicle ornaments

-

String of tinsel

-

Stringing lights on tree

-

Squirrel eating popcorn and cranberry garland off Christmas tree

Symbolism and interpretations[edit]

The earliest legend of the origin of a fir tree becoming a Christian symbol dates back to 723 AD, involving Saint Boniface as he was evangelizing Germany.[105] It is said that at a pagan gathering in Geismar where a group of people dancing under a decorated oak tree were about to sacrifice a baby in the name of Thor, Saint Boniface took an axe and called on the name of Jesus.[105] In one swipe, he managed to take down the entire oak tree, to the crowd’s astonishment.[105] Behind the fallen tree was a baby fir tree.[105] Boniface said, «let this tree be the symbol of the true God, its leaves are ever green and will not die.» The tree’s needles pointed to heaven and it was shaped triangularly to represent the Holy Trinity.[105]

When decorating the Christmas tree, many individuals place a star at the top of the tree symbolizing the Star of Bethlehem.[7][106] It became popular for people to also use an angel to top the Christmas tree in order to symbolize the angels mentioned in the accounts of the Nativity of Jesus.[8] Additionally, in the context of a Christian celebration of Christmas, the evergreen Christmas tree symbolizes eternal life; the candles or lights on the tree represent Christ as the light of the world.[6][107]

Production[edit]

A large scale Christmas tree farm in the United States

Undecorated Christmas trees for sale

Each year, 33 to 36 million Christmas trees are produced in America, and 50 to 60 million are produced in Europe. In 1998, there were about 15,000 growers in America (a third of them «choose and cut» farms). In that same year, it was estimated that Americans spent $1.5 billion on Christmas trees.[108] By 2016 that had climbed to $2.04 billion for natural trees and a further $1.86 billion for artificial trees. In Europe, 75 million trees worth €2.4 billion ($3.2 billion) are harvested annually.[109]

Natural trees[edit]

The most commonly used species are fir (Abies), which have the benefit of not shedding their needles when they dry out, as well as retaining good foliage color and scent; but species in other genera are also used.

In northern Europe most commonly used are:

- Norway spruce Picea abies (the original tree, generally the cheapest)

- Silver fir Abies alba

- Nordmann fir Abies nordmanniana

- Noble fir Abies procera

- Serbian spruce Picea omorika

- Scots pine Pinus sylvestris

- Stone pine Pinus pinea (as small table-top trees)

- Swiss pine Pinus cembra

In North America, Central America, South America and Australia most commonly used are:

- Douglas fir Pseudotsuga menziesii

- Balsam fir Abies balsamea

- Fraser Fir Abies fraseri

- Grand fir Abies grandis

- Guatemalan fir Abies guatemalensis

- Noble fir Abies procera

- Nordmann fir Abies nordmanniana

- Red fir Abies magnifica

- White fir Abies concolor

- Pinyon pine Pinus edulis

- Jeffrey pine Pinus jeffreyi

- Scots pine Pinus sylvestris

- Stone pine Pinus pinea (as small table-top trees)

- Norfolk Island pine Araucaria heterophylla

- Paraná pine Araucaria angustifolia (when young, resembles a Pine tree)

Several other species are used to a lesser extent. Less-traditional conifers are sometimes used, such as giant sequoia, Leyland cypress, Monterey cypress, and eastern juniper. Various types of spruce tree are also used for Christmas trees (including the blue spruce and, less commonly, the white spruce); but spruces begin to lose their needles rapidly upon being cut, and spruce needles are often sharp, making decorating uncomfortable. Virginia pine is still available on some tree farms in the southeastern United States; however, its winter color is faded. The long-needled eastern white pine is also used there, though it is an unpopular Christmas tree in most parts of the country, owing also to its faded winter coloration and limp branches, making decorating difficult with all but the lightest ornaments. Norfolk Island pine is sometimes used, particularly in Oceania, and in Australia, some species of the genera Casuarina and Allocasuarina are also occasionally used as Christmas trees. But, by far, the most common tree is the Pinus radiata Monterey pine. Adenanthos sericeus or Albany woolly bush is commonly sold in southern Australia as a potted living Christmas tree. Hemlock species are generally considered unsuitable as Christmas trees due to their poor needle retention and inability to support the weight of lights and ornaments.

Some trees, frequently referred to as «living Christmas trees», are sold live with roots and soil, often from a plant nursery, to be stored at nurseries in planters or planted later outdoors and enjoyed (and often decorated) for years or decades. Others are produced in a container and sometimes as topiary for a porch or patio. However, when done improperly, the combination of root loss caused by digging, and the indoor environment of high temperature and low humidity is very detrimental to the tree’s health; additionally, the warmth of an indoor climate will bring the tree out of its natural winter dormancy, leaving it little protection when put back outside into a cold outdoor climate. Often Christmas trees are a large attraction for living animals, including mice and spiders. Thus, the survival rate of these trees is low.[110] However, when done properly, replanting provides higher survival rates.[111]

European tradition prefers the open aspect of naturally grown, unsheared trees, while in North America (outside western areas where trees are often wild-harvested on public lands)[112] there is a preference for close-sheared trees with denser foliage, but less space to hang decorations.

In the past, Christmas trees were often harvested from wild forests, but now almost all are commercially grown on tree farms. Almost all Christmas trees in the United States are grown on Christmas tree farms where they are cut after about ten years of growth and new trees planted. According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s agriculture census for 2007, 21,537 farms were producing conifers for the cut Christmas tree market in America, 5,717.09 square kilometres (1,412,724 acres) were planted in Christmas trees.[113]

The life cycle of a Christmas tree from the seed to a 2-metre (7 ft) tree takes, depending on species and treatment in cultivation, between eight and twelve years. First, the seed is extracted from cones harvested from older trees. These seeds are then usually grown in nurseries and then sold to Christmas tree farms at an age of three to four years. The remaining development of the tree greatly depends on the climate, soil quality, as well as the cultivation and how the trees are tended by the Christmas tree farmer.[114]

Artificial trees[edit]

An artificial Christmas tree

The first artificial Christmas trees were developed in Germany during the 19th century,[115][116][self-published source?] though earlier examples exist.[117] These «trees» were made using goose feathers that were dyed green,[115] as one response by Germans to continued deforestation.[116] Feather Christmas trees ranged widely in size, from a small 5-centimeter (2 in) tree to a large 2.5-meter (98 in) tree sold in department stores during the 1920s.[118] Often, the tree branches were tipped with artificial red berries which acted as candle holders.[119]

Over the years, other styles of artificial Christmas trees have evolved and become popular. In 1930, the U.S.-based Addis Brush Company created the first artificial Christmas tree made from brush bristles.[120] Another type of artificial tree is the aluminum Christmas tree,[116] first manufactured in Chicago in 1958,[121] and later in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, where the majority of the trees were produced.[122] Most modern artificial Christmas trees are made from plastic recycled from used packaging materials, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC).[116] Approximately 10% of artificial Christmas trees are using virgin suspension PVC resin; despite being plastic most artificial trees are not recyclable or biodegradable.[123]

Other trends developed also in the early 2000s. Optical fiber Christmas trees come in two major varieties; one resembles a traditional Christmas tree.[124] One Dallas-based company offers «holographic mylar» trees in many hues.[117] Tree-shaped objects made from such materials as cardboard,[125] glass,[126] ceramic or other materials can be found in use as tabletop decorations. Upside-down artificial Christmas trees became popular for a short time and were originally introduced as a marketing gimmick; they allowed consumers to get closer to ornaments for sale in retail stores and opened up floor space for more products.[127]

Artificial trees became increasingly popular during the late 20th century.[116] Users of artificial Christmas trees assert that they are more convenient, and, because they are reusable, much cheaper than their natural alternative.[116] They are also considered much safer,[128] as natural trees can be a significant fire hazard. Between 2001 and 2007, artificial Christmas tree sales in the U.S. jumped from 7.3 million to 17.4 million.[129] Currently, it is estimated that around 58% of Christmas trees used in the United States are artificial, while numbers in the United Kingdom are indicated to be around 66%.[130]

- Artificial trees

-

A tree with fibre optic lights

-

White Christmas tree

-

Spanish artificial Christmas tree

-

-

Artificial tree

-

Environmental issues[edit]

The debate about the environmental impact of artificial trees is ongoing. Generally, natural tree growers contend that artificial trees are more environmentally harmful than their natural counterparts.[129] However, trade groups such as the American Christmas Tree Association, continue to refute that artificial trees are more harmful to the environment, and maintain that the PVC used in Christmas trees has excellent recyclable properties.[131]

Live trees are typically grown as a crop and replanted in rotation after cutting, often providing suitable habitat for wildlife.[132] Alternately, live trees can be donated to livestock farmers who find that such trees uncontaminated by chemical additives are excellent fodder.[133] In some cases management of Christmas tree crops can result in poor habitat since it sometimes involves heavy input of pesticides.[134]

Concerns have been raised[by whom?] about people cutting down old and rare conifers, such as the Keteleeria evelyniana and Abies fraseri, for Christmas trees.[citation needed]

Real or cut trees are used only for a short time, but can be recycled and used as mulch, wildlife habitat, or used to prevent erosion.[135][136][137] Real trees are carbon-neutral, they emit no more carbon dioxide by being cut down and disposed of than they absorb while growing.[138] However, emissions can occur from farming activities and transportation. An independent life-cycle assessment study, conducted by a firm of experts in sustainable development, states that a natural tree will generate 3.1 kg (6.8 lb) of greenhouse gases every year (based on purchasing 5 km (3.1 mi) from home) whereas the artificial tree will produce 48.3 kg (106 lb) over its lifetime.[139] Some people use living Christmas or potted trees for several seasons, providing a longer life cycle for each tree. Living Christmas trees can be purchased or rented from local market growers. Rentals are picked up after the holidays, while purchased trees can be planted by the owner after use or donated to local tree adoption or urban reforestation services.[140] Smaller and younger trees may be replanted after each season, with the following year running up to the next Christmas allowing the tree to carry out further growth.

Most artificial trees are made of recycled PVC rigid sheets using tin stabilizer in the recent years. In the past, lead was often used as a stabilizer in PVC, but is now banned by Chinese laws.[citation needed] The use of lead stabilizer in Chinese imported trees has been an issue of concern among politicians and scientists over recent years. A 2004 study found that while in general artificial trees pose little health risk from lead contamination, there do exist «worst-case scenarios» where major health risks to young children exist.[141] A 2008 United States Environmental Protection Agency report found that as the PVC in artificial Christmas trees aged it began to degrade.[142] The report determined that of the fifty million artificial trees in the United States approximately twenty million were nine or more years old, the point where dangerous lead contamination levels are reached.[142] A professional study on the life-cycle assessment of both real and artificial Christmas trees revealed that one must use an artificial Christmas tree at least twenty years to leave an environmental footprint as small as the natural Christmas tree.[139]

-

Discarded trees by garbage dumpsters

-

Christmas tree recycling point (point recyclage de sapins)

-

Woodchipping Christmas trees

Religious issues[edit]

Under the Marxist-Leninist doctrine of state atheism in the Soviet Union, after its foundation in 1917, Christmas celebrations—along with other religious holidays—were prohibited as a result of the Soviet anti-religious campaign.[143][144][86] The League of Militant Atheists encouraged school pupils to campaign against Christmas traditions, among them being the Christmas tree, as well as other Christian holidays, including Easter; the League established an anti-religious holiday to be the 31st of each month as a replacement.[145] With the Christmas tree being prohibited in accordance with Soviet anti-religious legislation, people supplanted the former Christmas custom with New Year’s trees.[86][146] In 1935, the tree was brought back as New Year tree and became a secular, not a religious holiday.

Pope John Paul II introduced the Christmas tree custom to the Vatican in 1982. Although at first disapproved of by some as out of place at the centre of the Roman Catholic Church, the Vatican Christmas Tree has become an integral part of the Vatican Christmas celebrations,[147] and in 2005 Pope Benedict XVI spoke of it as part of the normal Christmas decorations in Catholic homes.[148] In 2004, Pope John Paul called the Christmas tree a symbol of Christ. This very ancient custom, he said, exalts the value of life, as in winter what is evergreen becomes a sign of undying life, and it reminds Christians of the «tree of life»,[149] an image of Christ, the supreme gift of God to humanity.[150] In the previous year he said: «Beside the crib, the Christmas tree, with its twinkling lights, reminds us that with the birth of Jesus the tree of life has blossomed anew in the desert of humanity. The crib and the tree: precious symbols, which hand down in time the true meaning of Christmas.»[151] The Catholic Church’s official Book of Blessings has a service for the blessing of the Christmas tree in a home.[152] The Episcopal Church in The Anglican Family Prayer Book, which has the imprimatur of The Rt. Rev. Catherine S. Roskam of the Anglican Communion, has long had a ritual titled Blessing of a Christmas Tree, as well as Blessing of a Crèche, for use in the church and the home; family services and public liturgies for the blessing of Christmas trees are common in other Christian denominations as well.[153][154]

Chrismon trees, which find their origin in the Lutheran Christian tradition though now used in many Christian denominations such as the Catholic Church and Methodist Church, are used to decorate churches during the liturgical season of Advent; during the period of Christmastide, Christian churches display the traditional Christmas tree in their sanctuaries.[155]

In 2005, the city of Boston renamed the spruce tree used to decorate the Boston Common a «Holiday Tree» rather than a «Christmas Tree».[156] The name change was reversed after the city was threatened with several lawsuits.[157]

-

St Boniface felling the Donar Oak

-

A 1931 edition of the Soviet magazine Bezbozhnik, distributed by the League of Militant Atheists, depicting an Orthodox Christian priest being forbidden to cut down a tree for Christmas

See also[edit]

- Badnjak

- Christmas traditions

- Christmas tree controversies

- Eiresione

- Festive ecology

- Festivus pole

- Hanging of the greens

- Hanukkah bush

- Kadomatsu

- Legend of the Christmas Spider

- Nardoqan

- New Year tree

- Tree worship

- Weihnachten

- Yule log

Notes[edit]

- ^ The story, not recounted in the vitae written in his time, appears in a BBC Devon website, «Devon Myths and Legends», and in a number of educational storybooks, including St. Boniface and the Little Fir Tree: A Story to Color by Jenny Melmoth and Val Hayward (Warrington: Alfresco Books 1999 ISBN 1-873727-15-1), The Brightest Star of All: Christmas Stories for the Family by Carrie Papa (Abingdon Press 1999 ISBN 978-0-687-64813-9) and «How Saint Boniface Kept Christmas Eve» by Mary Louise Harvey in The American Normal Readers: Fifth Book, 207-22. Silver, Burdett and Co. 1912.

- ^ In 1829 the diarist Greville, visiting Panshanger country house, describes three small Christmas trees «such as is customary in Germany», which Princess Lieven had put up.[50]

References[edit]

- ^ Travers, Penny (19 December 2016). «The history of the Christmas tree». Australia: ABC News. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Perry, Joe (27 September 2010). Christmas in Germany: A Cultural History. University of North Carolina Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780807899410.

A chronicle from Strasbourg, written in 1604 and widely seen as the first account of a Christmas tree in German-speaking lands, records that Protestant artisans brought fir trees into their homes in the holiday season and decorated them with «roses made of colored paper, apples, wafers, tinsel, sweetmeats, etc.» […] The Christmas tree spread out in German society from the top down, so to speak. It moved from elite households to broader social strata, from urban to rural areas, from the Protestant north to the Catholic south, and from Prussia to other German states.

- ^ Christmas trees were hung in St. George’s Church, Sélestat since 1521:«Office de la Culture de Sélestat—The history of the Christmas tree since 1521» (PDF). 18 December 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2013.

- ^ Dunphy, John J. (26 November 2010). From Christmas to Twelfth Night in Southern Illinois. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. p. 28. ISBN 9781614232537.

Having a Christmas tree became so closely identified with following Luther’s path that German Catholics initially wanted nothing to do with this symbol of Protestantism. Their resistance endured until the nineteenth century, when Christmas trees finally began finding their way into Catholic homes.

- ^ a b Kelly, Joseph F. (2010). The Feast of Christmas. Liturgical Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780814639320.

German Lutherans brought the decorated Christmas tree with them; the Moravians put lighted candles on those trees.

- ^ a b c Becker, Udo (1 January 2000). The Continuum Encyclopedia of Symbols. A & C Black. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8264-1221-8.

In Christianity, the Christmas tree is a symbol of Christ as the true tree of life; the candles symbolize the «light of the world» that was born in Bethlehem; the apples often used as decorations set up a symbolic relation to the paradisal apple of knowledge and thus to the original sin that Christ took away so that the return to Eden-symbolized by the Christmas tree-is again possible for humanity.

- ^ a b Mandryk, DeeAnn (25 October 2005). Canadian Christmas Traditions. James Lorimer & Company. p. 67. ISBN 9781554390984.

The eight-pointed star became a popular manufactured Christmas ornament around the 1840s and many people place a star on the top of their Christmas tree to represent the Star of Bethlehem.

- ^ a b Jones, David Albert (27 October 2011). Angels. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780191614910.

The same ambiguity is seen in that most familiar of angels, the angel on top of the Christmas tree. This decoration, popularized in the nineteenth century, recalls the place of the angels in the Christmas story (Luke 2:9–18).

- ^ Gillian Cooke, A Celebration of Christmas, 1980, page 62: «Martin Luther has been credited with the creation of the Christmas tree. […] The Christmas tree did not spring fully fledged into […] tree was slow to spread from its Alsatian home, partly because of resistance to its supposed Lutheran origins.»

- ^ a b Crump, William D. (15 September 2001). The Christmas Encyclopedia, 3d ed. McFarland. p. 386. ISBN 9780786468270.

Christmas trees in the countryside did not appear until World War I, although Slovenians of German ancestry were decorating trees before then. Traditionally, the family decorates their Christmas tree on Christmas Eve with electric lights, tinsel, garlands, candy canes, other assorted ornaments, and topped with an angel figure or star. The tree and Nativity scene remain until Candlemas (February 2)

- ^ «Candlemas». British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

Any Christmas decorations not taken down by Twelfth Night (January 5th) should be left up until Candlemas Day and then taken down.

- ^ Foley, Daniel J. (1999). The Christmas Tree. Omnigraphics. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-55888-286-7.

- ^ a b Dues, Greg (2008). Advent and Christmas. Bayard. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-1-58595-722-4.

Next to the Nativity scene, the most popular Christmas tradition is to have a Christmas tree in the home. This custom is not the same as bringing a Yule tree or evergreens into the home, originally popular during the month of the winter solstice in Germany.

- ^ a b Karas, Sheryl (1998). The Solstice Evergreen: history, folklore, and origins of the Christmas tree. Aslan. pp. 103–04. ISBN 978-0-944031-75-9.

- ^ «History of Christmas Trees». History. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Haidle, Helen (2002). Christmas Legends to Remember’. David C Cook. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-56292-534-5.

- ^ Debbie Trafton O’Neal, David LaRochelle (2001). Before and After Christmas. Augsburg Fortress. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8066-4156-0.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Senn, Frank C. (2012). Introduction to Christian Liturgy. Fortress Press. p. 118. ISBN 9781451424331.

The Christmas tree as we know it seemed to emerge in Lutheran lands in Germany in the sixteenth century. Although no specific city or town has been identified as the first to have a Christmas tree, records for the Cathedral of Strassburg indicate that a Christmas tree was set up in that church in 1539 during Martin Bucer’s superintendency.

- ^ «The Christmas Tree». Lutheran Spokesman. 29–32. 1936.

The Christmas tree became a widespread custom among German Lutherans by the eighteenth century.

- ^ Blainey, Geoffrey (24 October 2013). A Short History of Christianity. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 418. ISBN 9781442225909.

Many Lutherans continued to set up a small fir tree as their Christmas tree, and it must have been a seasonal sight in Bach’s Leipzig at a time when it was virtually unknown in England, and little known in those farmlands of North America where Lutheran immigrants congregated.

- ^ Ehrsam, Roger (1999). Le Vieux Turckheim. Ville de Turckheim: Jérôme Do Bentzinger. ISBN 978-2906238831.

- ^ Lazowski, Philip (2004). Understanding Your Neighbor’s Faith. KTAV Publishing House. pp. 203–04. ISBN 978-0-88125-811-0.

- ^ Foley, Michael P. (2005). Why Do Catholics Eat Fish on Friday?. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4039-6967-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ball, Ann (1997). Catholic Traditions in Crafts. Our Sunday Visitor. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-87973-711-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Christmas tree». Encyclopædia Britannica. 2003.

The modern Christmas tree […] originated in western Germany. The main prop of a popular medieval play about Adam and Eve was a fir tree hung with apples (paradise tree) representing the Garden of Eden. The Germans set up a paradise tree in their homes on 24 December, the religious feast day of Adam and Eve. They hung round white discs on it (symbolizing the host, the Christian sign of Christ’s body in the Eucharist); in a later tradition, the wafers were replaced by cookies of various shapes. Candles, too, were often added as the symbol of Christ. In the same room, during the Christmas season, was the Christmas pyramid, a triangular construction of wood, with shelves to hold Christmas figurines, decorated with evergreens, candles, and a star. By the 16th century, the Christmas pyramid and paradise tree had merged, becoming the Christmas tree.

- ^ Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (National Library of Portugal)—Codices Alcobacenses ([1] Archived 21 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine ); [BN: cod. alc. CLI / 64, Page. 330] Translated from original Portuguese

- ^ Huckabee, Tyler (9 December 2021). «No, Christmas Trees Don’t Have ‘Pagan’ Roots». Relevant Magazine. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

have a lot of historical examples of various ancient religious communities decorating trees (including, but not limited to, the Book of Jeremiah) but it’s a real reach to connect any of it to modern Christmas trees as we think of them. Scholars call this pareidolia – where we connect new data with something we already know about to make sense of it. We read about ancient people decorating trees, and we immediately think «like a Christmas tree,» whether or not there’s any actual connection. And, in this case, there’s not.

- ^ «Christmas tree». Encyclopædia Britannica. 2012. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ a b «BBC Religion & Ethics—Did the Romans invent Christmas?». BBC Religion & Ethics. 17 December 2012. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Churco, Jennie M. (December 1938). «Christmas and the Roman Saturnalia». The Classical Outlook. 16 (3): 25–26. JSTOR 44006272 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Fritz Allhoff, Scott C. Lowe (2010). Christmas. John Wiley & Sons.

His biographer, Eddius Stephanus, relates that while Boniface was serving as a missionary near Geismar, Germany, he had enough of the locals’ reverence for the old gods. Taking an axe to an oak tree dedicated to Norse god Thor, Boniface chopped the tree down and dared Thor to zap him for it. When nothing happened, Boniface pointed out a young fir tree amid the roots of the oak and explained how this tree was a more fitting object of reverence as it pointed towards the Christian heaven and its triangular shape was reminiscent of the Christian trinity.

- ^ Amelung, Friedrich (1885). Geschichte der Revaler Schwarzenhäupter: von ihrem Ursprung an bis auf die Gegenwart: nach den urkundenmäßigen Quellen des Revaler Schwarzenhäupter-Archivs 1, Die erste Blütezeit von 1399–1557 [History of the Tallinn Blackheads: from their origins until the present day: from the testimonial sources of the Tallinn Blackheads archive. 1: The first golden age of 1399–1557] (in German). Reval: Wassermann.

- ^ Weber-Kellermann, Ingeborg (1978). Das Weihnachtsfest. Eine Kultur- und Sozialgeschichte der Weihnachtszeit [Christmas: A cultural and social history of Christmastide] (in German). Bucher. p. 22. ISBN 978-3-7658-0273-7.

Man kann als sicher annehmen daß die Luzienbräuche gemeinsam mit dem Weinachtsbaum in Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts aus Deutschland über die gesellschaftliche Oberschicht der Herrenhöfe nach Schweden gekommen sind. (English: One can assume with certainty that traditions of lighting, together with the Christmas tree, crossed from Germany to Sweden in the 19th century via the princely upper classes.)

- ^ Foley, Michael P. (6 September 2022). Why We Kiss under the Mistletoe: Christmas Traditions Explained. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-68451-281-2.

- ^ Janota E. Lud i jego zwyczaje. Lwów, 1878, str. 41–42

- ^ «Zwyczaje, obrzędy i tradycje w Polsce. Mały słownik». Księgarnia Mateusza (in Polish). Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Rok karpacki: obrzędy doroczne w Karpatach polskich Urszula Janicka-Krzywda. 1988, s. 13 «W całych Karpatach znano drzewko wigilijne zwane podłaźnikiem. Był to wierzchołek jodły zawieszany u powały szczytem na. dół, ubierany jabłkami i tzw. światami»

- ^ «Słomiane snopy i podłaźniczki – to nasze poprzedniki choinki. Te zaś ozdabiano jabłkami». Niezależna. 24 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ «News Detail». Jüdisches Museum Wien (in German). Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ «Danmarks første juletræ blev tændt i 1808». Kristelig Dagblad. 17 December 2008. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013.

- ^ Marbach, Johannes (1859). Die heilige Weihnachtszeit nach Bedeutung, Geschichte, Sitten und Symbolen [The holy Christmas season for meaning, history, customs and symbols] (in German). p. 416.

Was ist auch eine deutsche Christenfamilie am Christabend ohne Christbäumchen? Zumal in der Fremde, unter kaltherzigen Engländern und frivolen Franzosen, unter den amerikanischen Indianern und den Papuas von Australien. Entbehren doch die nichtdeutschen Christen neben dem Christbäumchen noch so viele Züge deutscher Gemüthlichkeit. [English: What would a German Christian family do on Christmas Eve without a Christmas tree? Especially in foreign lands, among cold-hearted Englishmen and frivolous Frenchmen, among the American Indians and the Papua of Australia. Apart from the Christmas tree, the non-German Christians suffer from a lack of a great many traits of German ‘Gemütlichkeit’.]

- ^ Hermelink, Jan (2003). «Weihnachtsgottesdienst» [Christmas worship]. In Grethlein, Christian; Ruddat, Günter (eds.). Liturgisches Kompendium (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 290. ISBN 978-3-525-57211-5.

- ^ «Zgodovina okraševanja: Božično drevesce ali novoletna jelka» (in Slovenian). dormeo.net. 15 December 2021.

- ^ «Zgodovina okraševanja: Božično drevo s sporočili» (in Slovenian). vecer.com. 10 December 2021.

- ^ «Rojstvo tradicije: od bršljana, bele omele do okraskov polne jelke» (in Slovenian). mestnik.si. 4 December 2021.

- ^ «Kako smo nekoč praznovali novo leto» (in Slovenian). ljubljana.si. 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Bingham, John (25 December 2016). «Queen’s Christmas Day message: Monarch quotes from Bible to address a nation shaken by year of atrocities». telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Stow, John (1603). Survey of London. London: John Windet. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

Against the feast of Christmas every man’s house, as also the parish churches, were decked with holm, ivy, bays, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green.

- ^ «The History of the Christmas Tree at Windsor». Archived from the original on 24 December 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Hole, Christine (1950). English Custom and Usage. London: B. T. Batsford Ltd. p. 16.

- ^ Victoria, Queen (1912). Reginald Brett, 2nd Viscount Esher (ed.). The girlhood of Queen Victoria: a selection from Her Majesty’s diaries. J. Murray.

- ^ Marie Claire Lejeune (2002). Compendium of symbolic and ritual plants in Europe. Man & Culture. p. 550. ISBN 978-90-77135-04-4.

- ^ «GERMAN CHRISTMAS TREES. The nobility and gentry are respectfully informed that these handsome JUVENILE CHRISTMAS PRESENTS are supplied and elegantly fitted up …»:Times [London, England] 20 December 1842, p. 1.

- ^ The Christmas Tree: published by Darton and Clark, London. «The ceremony of the Christmas tree, so well known throughout Germany, bids fair to be welcomed among us, with the other festivities of the season, especially now the Queen, within her own little circle, has set the fashion, by introducing it on the Christmas Eve in her own regal palace.» Book review of The Christmas Tree from the Weekly Chronicle, 14 December 1844, quoted in an advert headlined «A new pleasure for Christmas» in The Times, 23 December 1844, p. 8.

- ^ Caroline Augusta Edgcumbe, née Feilding, Lady Mt Edgcumbe (1808–1881); William Henry Fox-Talbot’s half-sister.

- ^ Correspondence of William Henry Fox-Talbot, British Library, London, Manuscripts—Fox Talbot Collection, envelope 20179 [2] Archived 11 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Godfrey and Margaret Scheele (1977). The Prince Consort, Man of many Facets: The World and The Age of Prince Albert. Oresko Books. p. 78. ISBN 9780905368061.

- ^ At the beginning of the year the custom was well-enough known for The Times to compare the January budget of 1848 with gifts handed out beneath «the Christmas tree»: The Times (London, England), 21 January 1848, p. 4.

- ^ Special Christmas supplement edition, published 23 December 1848.

- ^ The Times (London, England), 27 December 1848. p. 7

- ^ «Now the best Christmas box / You can give to the young / Is not toys, nor fine playthings, / Nor trees gaily hung …»: Manchester Guardian, Saturday, 5 January 1856, p. 6.

- ^ Manchester Guardian, 24 January 1856, p. 3: the death of Caroline Luttrell of Kilve Court, Somerset.

- ^ The Times (London, England), 28 December 1858, p. 8.

- ^ The Poor Children’s Yuletide Association. The Times (London, England), 20 December 1906, p. 2. «The association sent 71 trees ‘bearing thousands of toys’ to the poorest districts of London.»

- ^ «A Merry Christmas»: The Times (London, England), 27 December 1918, p. 2: «… the so-called «Christmas tree» was out of favour. Large stocks of young firs were to be seen at Covent Garden on Christmas Eve, but found few buyers. It was remembered that the ‘Christmas tree’ has enemy associations.»

- ^ The next year a charity fair in aid of injured soldiers featured ‘a huge Christmas-tree’. ‘St. Dunstan’s Christmas Fair’. The Times (London, England), 20 December 1919, p. 9.

- ^ ‘Poor families in Lewisham and similar districts are just as particular about the shape of their trees as people in Belgravia …’ ‘Shapely Christmas Trees’: The Times (London, England), 17 December 1926, p. 11.

- ^ Christmas Tree Plantations. The Times (London, England), 11 December 1937, p. 11.

- ^ «Christmas tree grower Ivor Dungey gets award». BBC News. 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ «Chichilaki–Georgian version of Christmas tree». Georgian Journal. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ «Georgians rediscover Christmas tree traditions». BBC News. 21 December 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ 13 January 1864 Nassau Guardian

- ^ 28 December 1864 Nassau Guardian

- ^ Werner, Emmy E. (2006). In Pursuit of Liberty: Coming of Age in the American Revolution. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 115. ISBN 9780275993061.

- ^ Harding, Anneliese (1994). John Lewis Krimmel: Genre Artist of the Early Republic. Winterthur, DE: Winterthur Publications. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-912724-25-6 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Alfred Lewis Shoemaker (1999) [1959]. Christmas in Pennsylvania: a folk-cultural study. Stackpole Books. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-8117-0328-4.

- ^ Karal Ann Marling (2000). Merry Christmas! Celebrating America’s greatest holiday. Harvard University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-674-00318-7.

- ^ «White House Tree». White House Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Joseph Wenzel IV (30 November 2015). «First Decorated Christmas Tree in Windsor Locks». WFSB. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ «The History of Christmas». Gareth Marples. Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ «Professor Brought Christmas Tree to New England». Harvard University Gazette. 12 December 1996. Archived from the original on 23 August 1999. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ «They’re Still Cheering Man Who Gave America Christmas Tree». Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune. 24 December 1938. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ «Charles Minnigerode (1814–1894)». Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ^ ‘Notes and Queries’, volume 8 (217), 24 December 1853, p.615

- ^ «A Brief History of Electric Christmas Lighting in America». oldchristmastreelights.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Echo of Islam. MIG. 1993.

In the former Soviet Union, fir trees were usually put up to mark New Year’s day, following a tradition established by the officially atheist state.

- ^ Harper, Timothy (1999). Moscow Madness: Crime, Corruption, and One Man’s Pursuit of Profit in the New Russia. McGraw-Hill. p. 72. ISBN 9780070267008.

During the decades of official state atheism in the Soviet era, Christmas had been a nonholiday.

- ^ Bowler, Gerry (27 July 2011). Santa Claus. ISBN 9781551996080. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ «1 мая собираются праздновать 59% россиян» [1 May going to celebrate 59% of Russians] (in Russian). 27 April 2012. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

New Year is among the most important holidays for 81% of Russians, while Christmas is such only for 19%, ranking after Victory Day, Easter, International Women’s Day.

- ^ Belk, Russell (2000). «Materialism and the Modern U.S. Christmas». Advertising & Society Review. 1. doi:10.1353/asr.2000.0001. S2CID 191578074. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ a b «Lighting of the National Christmas Tree». National Park Service. Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ «Flashback Blog: The World’s Largest Decorated Christmas Tree». The Palm Beach Post. 3 December 2009. Archived from the original on 5 December 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ ‘Manchester’s Gift To Lille … (FROM G. WARD PRICE.)’ The Times (London, England),21 December 1918, p.7

- ^ «Town twinning: Bergen, Norway». Newcastle City Council. Archived from the original on 25 April 2007.

- ^ «DC: Christmas Tree Lighting at Union Station». Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Dixon, Sandy (30 October 2013). Everlasting Light: A Resource for Advent Worship. Chalice Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780827208377.

Many congregations decorate the sanctuary for the Advent season in a service called Hanging of the Greens.

- ^ Michelin (10 October 2012). Germany Green Guide Michelin 2012–2013. Michelin. p. 73. ISBN 9782067182110.

Advent – The four weeks before Christmas are celebrated by counting down the days with an advent calendar, hanging up Christmas decorations and lightning an additional candle every Sunday on the four-candle advent wreath.

- ^ Mazar, Peter (2000). School Year, Church Year: Customs and Decorations for the Classroom. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 161. ISBN 978-1568542409.

- ^ Blainey, Geoffrey (2004). Black Kettle and Full Moon. Penguin Group Australia. ISBN 978-1-74228-327-2.

But towards the end of the nineteenth century, in the weatherboard halls of a few townships, a tree would annually be set up, usually on Christmas Eve.

- ^ A Study Guide for William Shakespeare’s «Twelfth Night» (2 ed.). Cengage Learning. 2016. p. 29. ISBN 9781410361349.

Twelfth Night saw people feasting and taking down Christmas decorations. The king cake is traditionally served in France and England on the Twelfth Night to commemorate the journey of the Magi to visit the Christ child.

- ^ Edworthy, Niall (7 October 2008). The Curious World of Christmas. Penguin Group. p. 83. ISBN 9780399534577.

The time-honoured epoch for taking down Christmas decorations from Church and house in Candlemas Day, February 2nd. Terribly withered they are by that time. Candlemas in old times represented the end of the Christmas holidays, which, when «fine old leisure» reigned, were far longer than they are now.

- ^ Roud, Steve (31 January 2008). The English Year. Penguin Books Limited. p. 690. ISBN 9780141919270.

As indicated in Herrick’s poem, quoted above, in the mid seventeenth century Christmas decorations were expected to stay in place until Candlemas (2 February), and this remained the norm until the nineteenth century.

- ^ Groome, Imogen (31 December 2016). «When is Twelfth Night and what does it mean?». Metro. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

Twelfth Night 2017 is on Thursday 5 January, which is when we’re meant to put away our Christmas decorations or there’ll be bad luck in the year ahead. If you miss the date, some believe it’s necessary to keep decorations up until Candlemas on 2 February – or you’ll definitely have a rubbish year.

- ^ «Candlemas». BBC. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

Any Christmas decorations not taken down by Twelfth Night (January 5th) should be left up until Candlemas Day and then taken down.

- ^ a b c d e Forbes, Bruce David (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-520-25802-0.

… in 723 Saint Boniface encountered winter sacrifices being conducted in front of a mighty oak tree dedicated to Thor near Geismar, in what is now Germany. In anger, Boniface seized an axe and felled Thor’s oak in one mighty blow. The gathering of local citizens expected Thor to strike Boniface with a bolt of lightning, and when lightning failed to appear, Boniface proclaimed it a sign of superiority of the Christian God. He pointed to a young fir tree growing at the roots of the fallen oak, with its branches pointing to heaven, and said that it was a holy tree, the tree of the Christ child who brought eternal life. […] Also, it is said that Boniface explained the triangular shape of the fir tree as an illustration of the Trinity.

- ^ Wells, Dorothy (1897). «Christmas in Other Lands». The School Journal. 55: 697–8.

Christmas is the occasional of family reunions. Grandmother always has the place of honor. As the time approaches for enjoying the tree, she gathers her grandchildren about her, to tell them the story of the Christ child, with the meaning of the Christ child, with the meaning of the Christmas tree; how the evergreen is meant to represent the life everlasting, the candle lights to recall the light of the world, and the star at the top of the tree is to remind them of the star of Bethlehem.

- ^ Crump, William D. (2006). The Christmas Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7864-2293-7.

the evergreen tree (itself symbolic of eternal life through Christ)

- ^ Gary A. Chastagner and D. Michael Benson (2000). «The Christmas Tree». Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ^ Yanofsky, David (21 December 2017). «What the Christmas tree industrial complex looks like from space». Quartz. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ «Living Christmas Trees». Clemson University. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ «Christmas tree». Department of Forestry, Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012.

- ^ «BLM and Forest Service Christmas tree permits available». Bureau of Land Management. 30 November 2004. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ «2007 Census of Agriculture: Specialty Crops (Volume 2, Subject Series, Part 8)» (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. November 2009. Table 1, page 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ «Unsere kleine Baumschule—Wissenswertes» [Our little nursery: Trivia] (in German). 2010. Archived from the original on 25 November 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ a b Bruce David Forbes (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. pp. 121–22. ISBN 978-0-5202-5104-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Hewitt, James (2007). The Christmas Tree. Lulu.com. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-1430308201.[self-published source]

- ^ a b Perkins, Broderick (12 December 2003). «Faux Christmas Tree Crop Yields Special Concerns». Realty Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Silverthorne, Elizabeth (1994). Christmas in Texas. Texas A&M University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8909-6578-8.

- ^ Karal Ann Marling (2000). Merry Christmas!: Celebrating America’s Greatest Holiday. Harvard University Press. pp. 58–62. ISBN 978-0-674-00318-7.

- ^ Cole, Peter (2002). Christmas Trees: Fun and Festive Ideas. Chronicle Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8118-3577-0.

- ^ Fortin, Cassandra A. (26 October 2008). «It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas (1958)». The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Candice Gaukel Andrews (2006). Great Wisconsin Winter Weekends. Big Earth Publishing. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-9315-9971-9.

- ^ Berry, Jennifer (9 December 2008). «Fake Christmas Trees Not So Green». LiveScience. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Neer, Katherine (December 2006). «How Christmas Trees Work». howStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ «Table-top Christmas Tree». Popular Mechanics: 117. January 1937.

- ^ «Glass Christmas Tree, one-day course listing». Diablo Glass School. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ «Demand Grows for Upside Down Christmas Tree» (Audio). All Things Considered. NPR. 9 November 2005. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ «Christmas Tree Safety». About.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ a b Sharon Caskey Hayes (26 November 2008). «Grower says real Christmas trees are better for environment than artificial ones». Kingsport Times-News. Kingsport, Tennessee. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ «Christmas Tree Resource: Your Source On Xmas Decorations». Christmas Tree Source. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ «Facts on PVC Used in Artificial Christmas Trees». American Christmas Tree Association. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Sandborn, Dixie (2 December 2016). «Real Christmas trees: History, facts and environmental impacts». canr.msu.edu/. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ «Goats, elk happy to munch on your used Christmas trees». CBC News. 29 December 2014. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2015.