Приблизительное время чтения: 11 мин.

Память великомученика Феодора Тирона — 12 марта

Воин Феодор («Тирон» буквально — новобранец) — великомученик, память которого отмечается в субботу первой недели Великого поста.

Он жил в III веке при правлении императора Максимилиана. За то, что Феодор отказался принести жертву языческим богам и объявил себя христианином, воина бросили в тюрьму, жестоко пытали и, в конце концов, сожгли на костре. По преданию, огонь не повредил его останки. Их забрала христианка Евсевия и сохранила в своем доме. Позднее мощи святого были перенесены в Константинополь.

Накануне дня памяти святого Федора Тирона, в пятницу, после Литургии Преждеосвященных Даров, в храмах читают канон великомученику Феодору и раздают прихожанам коливо (вареные зерна пшеницы с медом). Это делается в память об одном удивительном событии. Дело в том, что в IV веке к власти в Константинополе пришел император Юлиан Отступник. Он притеснял христиан разными способами. Однажды в первую седмицу Великого поста, он приказал тайно окропить идоложертвенной кровью все продукты, которые продавались в городе. В ближайшую ночь местному архиепископу во сне явился великомученик Феодор и рассказал о кознях императора. Мученик повелел христианам не покупать идоложертвенную пищу, а сварить коливо из домашних запасов зерна.

Неделя 1‑я Великого поста. Торжество Православия — 13 марта

В церковнославянском «неделя» значит «воскресенье», а неделя в современном смысле слова называется «седмица». Каждое воскресенье Великого поста имеет особое посвящение.

В первое воскресенье Великого называется Торжество Православия в честь события, которое произошло в 843 году в Константинополе. Тогда царица Феодора собрала иерархов Церкви, одобрявших иконопочитание, и низложила иконоборческого патриарха Иоанна Грамматика. Так были воплощены решения VII Вселенского собора, который постановил почитать святые иконы.

Этот праздник решили сделать ежегодным, чтобы напоминать людям об опасности впадения в ересь. Отмечают Торжество Православия в первое воскресенье Великого поста, так как самое первое его празднование в 843 году пришлось именно на такой день. Тексты чина Торжества Православия говорят о победе Церкви над ересями и провозглашают постановления семи Вселенских соборов.

Неделя 2‑я Великого поста. Святителя Григория Паламы — 20 марта

Святитель Григорий Палама, архиепископ Фессалоникийский, — один из величайших богословов и учителей Церкви. Его главный вклад — учение о непрестанной молитве, исихии (молчания), нетварных энергиях и Фаворском свете. Святитель писал, что верующий человек способен (с Божией помощью) удалиться от греха настолько, чтобы удостоиться реальной встречи со Христом еще при жизни, увидеть нетварный фаворский свет, который был открыт апостолам на горе Преображения.

Преображение — одно из важнейших событий евангельской истории (праздник в честь него отмечается Церковью 19 августа). Однажды Христос, взяв с Собой учеников Петра, Иоанна и Иакова, взошел на гору помолиться. Во время молитвы лицо Его вдруг изменилось, а одежда стала сверкающей белизны. Ученики увидели, что с Ним беседуют пророки Моисей и Илья. Это поразило апостолов. Долгое время не только простой народ, но и ученики Христа считали Его прежде всего земным царем. В день Преображения Господь приоткрыл им завесу будущего и показал, что Он — Сын Божий. На иконах праздника Христа обычно изображают в ореоле «фаворского света» — необычайного сияния, которое увидели апостолы.

Пост — лучшее время для упражнений в воздержании и молитве, поэтому на второй неделе мы вспоминаем святителя Григория Паламу, который учил, что внутреннее преображение доступно каждому из нас.

Память 40 мучеников Севастийских — 22 марта

Сорок Севастийских мучеников — это воины-христиане, которые приняли мученическую смерть в 320 году при императоре Лицинии. Они были родом из Каппадокии (восток современной Турции) и служили в составе римского легиона, стоявшего в городе Севастии.

Военачальник приказал им принести жертву языческим богам, но воины отказались. Тогда их раздели и оставили на ночь на замерзшем озере. Рядом поставили тёплую баню, чтобы соблазнить их отречься от Христа. Наутро один из воинов не выдержал испытаний и побежал в баню, однако там сразу же упал замертво. Зато один из стражников по имени Аглаий, видя стойкость духа мучеников, добровольно разделся и присоединился к ним. По преданию, мученики не замерзли, простояв много часов на льду. Тогда стража перебила им голени, а затем сожгла. Обугленные кости мучеников бросили в воду, чтобы христиане не могли захоронить их. Но, как говорит житие, через три дня мученики явились во сне епископу Севастийскому Петру и попросили похоронить свои останки. Епископ с несколькими помощниками пошел к озеру и увидел, что кости мучеников светятся под водой ярким светом. Он собрал их и с честью похоронил.

Память Сорока мучеников относится числу наиболее чтимых праздников, поэтому в этот день облегчается строгость Великого поста и совершается литургия преждеосвященных Даров.

Существует также народная традиция готовить на праздник Сорока мучеников «жаворонки» — фигурки птиц из постного теста с глазами-изюминками. Эти птички символизируют улетающие к Богу души мучеников.

Неделя 3‑я Великого поста. Крестопоклонная — 27 марта

Великий пост подходит к своей середине, и верующие начинаютуставать от ограничений и напряженной духовной жизни. Чтобы ободрить их, Церковь предлагает вспомнить о цели постного подвига. Мы постимся, чтобы разделить с Христом Его страдания, а затем глубже прочувствовать радость Пасхи. В центре внимания в этот день — крест, главный христианский символ.

На воскресной всенощной Животворящий Крест Господень выносится в центр храма и остается там до пятницы. Под пение «Кресту Твоему поклоняемся, Владыко, и Святое Воскресение Твое славим» верующие совершают перед крестом поклоны. Крест напоминает нам о страданиях Спасителя, укрепляет в намерении духовно трудиться в ожидании Пасхи. Митрополит Антоний Сурожский говорил об этом так: «Крест нам явлен сейчас как надежда, как уверенность в Божией любви и в Его победе, как уверенность в том, что мы так любимы, что все возможно».

Благовещение Пресвятой Богородицы — 7 апреля

В этот день Дева Мария услышала радостную (благую) весть о том, что Она станет Матерью Спасителя мира.

Об событии Благовещения рассказывает Евангелие от Луки. Там говорится, что в шестой месяц после зачатия праведной Елизаветой святого Иоанна Предтечи Бог послал архангела Гавриила в город Назарет к Деве Марии с вестью о том, что она родит Спасителя мира.

Войдя к Марии, ангел произнес: «Радуйся, Благодатная! Господь с Тобою; благословенна Ты между жёнами». Он также добавил: «Не бойся, Мария, ибо Ты обрела благодать у Бога; и вот, зачнёшь во чреве, и родишь Сына, и наречёшь Ему имя: Иисус. Он будет велик и наречётся Сыном Всевышнего, и даст Ему Господь Бог престол Давида, отца Его; и будет царствовать над домом Иакова во веки, и Царству Его не будет конца». (Лк. 1:28-33) Слова архангела — первая добра весть от Бога для человечества после грехопадения. Теперь связь человека и Бога, прерванная грехом Адама и Евы, восстановлена, а значит, начинается новая страница истории человеческого рода.

Благовещение ежегодно отмечается 7 апреля — за девять месяцев до Рождества.

Неделя 4‑я Великого поста. Преподобного Иоанна Лествичника (VI в.) — 3 апреля

Преподобный Иоанн — подвижник шестого века, который сорок лет провёл в подвиге молчания и молитвы. Он написал духовное сочинение «Лествица» — наставление и руководство к духовной жизни. В этой книге путь христианина представлен как постепенное восхождение по лестнице (лествице).

«Настоящая книга показывает превосходнейший путь. Шествуя сим путем, увидим, что она непогрешительно руководит последующих ее указаниям, сохраняет их неуязвленными от всякого претыкания, и представляет нам лествицу утвержденную, возводящую от земного во святая святых, на вершине которой утверждается Бог любви», — говорится в «Лествице».

Похвала Пресвятой Богородицы. Суббота Акафиста — 9 апреля

Суббота пятой седмицы Великого поста называется Субботой акафиста (иначе — Похвалой Пресвятой Богородицы).

Акафист Пресвятой Богородице — хвалебный гимн Пресвятой Деве Марии, составленный в Византии между V и VII вв. Греческое слово «акафистос» означает «неседален», т. е. песнь, во время которой нельзя сидеть. Акафист Богородице долгое время был единственным в своем роде, но постепенно стали появляться другие богослужебные гимны, повторяющие его структуру. Сейчас есть множество акафистов — Господу Иисусу Христу, Божией Матери в связи с различными Ее иконами и праздниками, акафисты святым. Однако византийский Акафист Пресвятой Богородице продолжает занимать исключительное положение: это единственный акафист, исполнение которого предписано богослужебным уставом. Он поется на утрене субботы пятой седмицы Великого поста (фактически — в пятницу вечером).

Есть несколько версий о причинах появления праздника. С одной стороны, благодаря заступничеству Богородицы, по преданию, удалось избавить Константинополь от нашествия арабов и персов в VII веке. Также празднование связано с Благовещением Пресвятой Богородицы (до того, как датой празднования назначили 7 апреля, его совершали в пятую субботу Великого поста).

Неделя 5‑я Великого поста. Преподобной Марии Египетской (VI в.) — 10 апреля

В конце Великого поста мы вспоминаем святую, которая прошла долгий путь покаяния. Преподобная Мария родилась в Александрии в середине V века. В двенадцать лет она ушла из дома, влекомая порочной жизнью. Долго Мария жила в грехе: «Семнадцать лет, и даже больше, я совершала блуд со всеми, не ради подарка или платы, так как ничего ни от кого я не хотела брать, но я так рассудила, что даром больше будут приходить ко мне и удовлетворять мою похоть». Но внезапно Господь обратил ее к покаянию.

Это случилось, когда Мария случайно попала в Иерусалим и оказалась у храма Воскресения Христова. Все люди свободно входили в храм, а Марию останавливала невидимая сила. Так она поняла, что Господь не допускает ее войти в святое место.

Марию охватили страх и раскаяние. После этого она зашла внутрь. Молитва у Гроба Господня изменила грешницу: Мария оставила свою прошлую жизнь и ушла в Иорданскую пустыню. Там она провела почти пятьдесят лет в одиночестве, молясь и постясь. В пустыне ее встретил старец Зосима из Иорданского монастыря. Он беседовал с преподобной и был поражен ее праведностью. Также он видел, как во время молитвы она приподнималась над землей и переходила Иордан по воде как по суше. Год спустя старец причастил святую, а еще через год — нашел в пустыне ее тело и похоронил. По преданию, могилу ему помог выкопать лев.

Святой Серафим Саровский говорил, что разница между погибающим грешником и грешником, который находит путь к спасению, — в решимости. Примером такой решимости служит Мария Египетская.

Житие Марии Египетской читается за богослужением на пятой неделе Великого поста, в среду вечером, когда в храмах совершается утреня четверга, которую принято называть Стояние Марии Египетской (Мариино стояние). В 2022 году — 4 апреля, в понедельник вечером пятой недели Великого поста.

Лазарева суббота — 16 апреля

В этот день мы вспоминаем невероятное чудо — воскрешение Христом праведного Лазаря, который четыре дня был мертв.

Святой праведный Лазарь жил в Вифании и был братом Марфы и Марии. Христос часто посещал их. Незадолго до праздника Пасхи Лазарь заболел, и сестры сообщили об этом Христу. Нj Иисус ответил: «Эта болезнь не к смерти, а к славе Божией». Когда Спаситель пришел в Вифанию. Марфа встретила Его словами: «Господи! Если бы Ты был здесь, не умер бы брат мой. Но и теперь знаю: чего Ты ни попросишь у Бога, даст Тебе», на что Христос ответил: «Воскреснет брат твой». Вскоре пришла Мария и другие родственники. Видя, как они скорбят, Христос заплакал. Собравшиеся подошли к пещере, где был погребен Лазарь, и Христос велел отвалить закрывающий ее камень. Марфа напомнила, что Лазаря погребли уже четыре дня назад, и он смердит. А Христос помолился и возгласил: «Лазарь, выйди вон!». Умерший Лазарь вышел из гробницы, обвитый по рукам и ногам погребальными пеленами. В Писании говорится, что многие, видевшие это чудо, уверовали во Исуса Христа, а фарисеи «c этого дня положили убить Его» (Ин. 11:53). Спаситель сотворил чудо, разозлившее фарисеев, не только из-за любви к своему усопшему другу и его сестрам, но и чтобы показать людям, что всеобщее воскресение в день Страшного Суда — реальность.

По преданию, после Воскресения Христа Лазарь из-за гонений покинул Иудею. Он поселился на Кипре и впоследствии стал епископом. После своего воскресения Лазарь прожил еще около 30 лет.

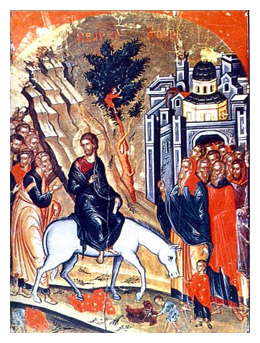

Неделя 6‑я. Неделя ва́ий («пальмовых ветвей»), иначе — Неделя цветоносная, Вербное воскресенье, Вход Господень в Иерусалим — 27 апреля

В этот праздник мы вспоминаем, как вскоре после воскрешения Лазаря Христос торжественно въехал в Иерусалим. Зная о совершённом чуде, горожане встречали Его как царя Иудеи и освободителя от римского владычества, кричали «Осанна сыну Давидову!» и бросали под ноги одежды и срезанные пальмовые ветви. Фарисеи призывали Иисуса запретить это делать, но Он отвечал: «Сказываю вам, что если они умолкнут, то камни возопиют» (Лк. 19, 40). В то же время Христос подчёркивает, что царство Его — не от мира сего. Он входит в Иерусалим не на коне, как все правители и полководцы, а на осле, символизирующем мир.

Тем не менее, народ приветствовал Христа как царя. Много веков иудеи ждали Мессию, о котором говорили пророки Ветхого завета. Кроме того, Иудея тогда находилась под римским владычеством, и многие воспринимали пророчества о Мессии как пророчество о великом земном царе.

До сих пор в Церкви сохраняется традиция встречать праздник с ветвями пальм в руках — они освящаются во время Всенощного бдения. Но поскольку в России и других северных странах пальмы не растут, верующие приносят в храм ветви вербы — первые весенние цветы.

Как и Лазарева суббота, Вход Господень в Иерусалим отстоит особняком от Великого поста. Эти дни подводят нас к особому периоду — Страстной седмице, которая хотя и является постной, но уже вплотную приближает нас ко дню Воскресения Христова. Страстная седмица (18—23 апреля) — особая неделя в церковном году, когда мы переживаем пребывание Христа в Иерусалиме, Его предательство Иудой, Тайную вечерю, Распятие и положение во гроб. Каждый день седмицы, ввиду важности вспоминаемых событий, называется «великим».

Родительские субботы Великого Поста

Родительские субботы — дни, когда мы особенно глубоко, вместе со всей Церковью, молимся за умерших родных и близких. В календаре Русской Православной Церкви восемь родительских суббот, и целых три из них приходятся на Великий пост. Дело в том, что во время Великого поста полная Литургия в будние дни не совершается, а значит — нет и поминовения усопших на проскомидии (первая часть Литургии, когда готовятся хлеб и вино для Причастия). Три великопостные родительские субботы призваны восполнить этот «пробел» — дать верующим возможность собраться для заупокойной молитвы.

Название «родительская», скорее всего, произошло от традиции называть покойных «родителями», то есть отошедшими к отцам. Еще одна версия — «родительскими» субботы стали именоваться, потому что христиане молитвенно поминали в первую очередь своих почивших родителей.

Суббота 2-й седмицы Великого поста — 19 марта 2022 года.

Суббота 3-й седмицы Великого поста — 26 марта 2022 года.

Суббота 4-й седмицы Великого поста — 2 апреля 2022 года.

Загрузка…

- Подготовительный период к Великому посту

- Календарь Великого Поста

- I. Святая Четыредесятница

- II. Страстная седмица (10–15 апреля)

- Светлое Христово Воскресение. Пасха – 16 апреля

- Недели после Пасхи

- Недели и особые дни поста: история и богослужение

- Неделя о мытаре и фарисее

- Отмена поста в седмицу после Недели о мытаре и фарисее

- Неделя о блудном сыне

- Недели мясопустная и сыропустная

- Неделя 1‑я Великого поста — Торжество Православия

- Неделя 2‑я Великого поста – святителя Григория Паламы

- Неделя 3‑я Великого поста – Крестопоклонная

- 4‑я и 5‑я Недели поста – памяти преподобных Иоанна Лествичника и Марии Египетской

- Четверг 5‑й седмицы — Мариино стояние

- Суббота 5‑я поста – Похвала Пресвятой Богородице

- 6‑я Неделя поста – Неделя Ваий, Вход Господень в Иерусалим

- Богослужение седмичных дней поста: особенности

- Какие службы совершаются в седмичные дни поста?

- Какие отличительные особенности имеет утреня?

- Чем великопостные часы отличаются от обычных вседневных часов?

- Что можно сказать об изобразительных в седмичные дни поста?

- Какие особенности имеет вечерня, совершаемая без литургии после изобразительных в понедельник, вторник и четверг?

- Что такое «конечное Трисвятое» и когда оно читается?

- Что можно вкратце сказать об особенностях великого повечерия?

- Статьи и книги о Великом посте

- Календарь питания Великого поста

- Трансляция из храма

Подготовительный период к Великому посту

Включает 3 седмицы и 4 Недели.

- Неделя о мытаре и фарисее (Лк.18:10–14) – 5 февраля.

- Седмица «сплошная» (нет поста в среду и пятницу) (6–11 февраля).

- Неделя о блудном сыне (Лк.15:11–32) – 12 февраля.

- Вселенская родительская (мясопустная) суббота – 18 февраля.

- Неделя мясопустная (последний день вкушения мяса), о Страшном суде (Мф.25:31–46) – 19 февраля.

- Седмица сырная (масленица), «сплошная» (20–25 февраля). В среду и пятницу сырной седмицы Литургии по причине поста не бывает (за исключением случаев, когда в эти дни случится Сретение Господне или храмовой праздник).

- Неделя сыропустная. Воспоминание Адамова изгнания. Прощёное воскресенье (Мф.6:14–21) – 26 февраля.

Календарь Великого Поста

I. Святая Четыредесятница

1 седмица (27 февраля – 4 марта)

- В первые 4 дня первой седмицы ВП (с понедельника по четверг, 27 февраля – 2 марта) за вечерним богослужением читается Великий (Покаянный) канон святителя Андрея Критского (VIII в.).

Неделя 1‑я Великого поста. Торжество Православия – 5 марта.

2 седмица (5–11 марта)

Неделя 2‑я Великого поста. Святителя Григория Паламы, архиеп. Фессалоникийского (†1359 г.) – 12 марта.

3 седмица (12–18 марта)

Неделя 3‑я Великого поста. Крестопоклонная (Мк.8:34–9:1) – 19 марта.

4 седмица (19–25 марта)

Неделя 4‑я Великого поста. Преп. Иоанна Лествичника (VI в.) – 26 марта.

5 седмица (26 марта – 1 апреля)

- Мари́ино стояние или Четверток Великого канона (чтение Великого канона свт. Андрея Критского, полностью, с чтением жития преп. Марии Египетской). Совершается в среду вечером. В 2022 году на этот день выпадает праздник Благовещения, поэтому переносится на день раньше, на вторник – 5 апреля.

- Благовещение Пресвятой Богородицы (7 апреля).

- Похвала Пресвятой Богородице. Суббота Акафиста – 1 апреля. Это единственный акафист, предусмотренный церковным Уставом; причём его пение совершается также только один раз в году – в субботу 5‑й седмицы Великого поста (реально поётся накануне, в пятницу вечером – 31 марта).

Неделя 5‑я Великого поста. Преп. Марии Египетской (VI в.) – 2 апреля.

6 седмица, «седмица вáий» (в переводе с греческого – «седмица пальмовых ветвей») – 2–8 апреля.

- В пятницу седмицы вáий, 7 апреля – окончание Святой четыредеся́тницы, то есть 40-дневного поста («душеполéзную совершив Четыредеся́тницу…», – поётся за вечерним богослужением).

- Лазарева суббота. Воспоминание воскрешения Иисусом Христом праведного Лазаря (Ин.11:1–45) – 8 апреля.

Неделя 6‑я, ва́ий (цветоносная, Ве́рбное воскресе́нье). Вход Госпо́день в Иерусали́м (Ин.12:1–18) – 9 апреля.

II. Страстная седмица (10–15 апреля)

- Великий Понедельник (10 апреля).

Темы богослужебных воспоминаний: Иосиф Прекрасный, проданный в Египет за 20 сребреников (Быт.37); проклятие бесплодной смоковницы, притча о злых виноградарях; пророчество о разрушении Иерусалима (Мф.21:18-43; 24:3-35). - Великий Вторник (11 апреля).

Притчи: о 10 девах и талантах; пророчество о Страшном Суде (Мф.24:36–26:2). - Великая Среда (12 апреля).

Покаяние грешницы, возлившей миро на ноги Иисуса, и предательство Иуды (Мф.26:6–16). - Последний раз читается молитва прп. Ефрема Сирина с 3‑мя великими поклонами. На вечерней службе в этот день все стараются принять участие в Таинстве Покаяния (Исповеди).

- Великий Четверг (13 апреля).

Воспоминание Тайной Вечери и установление Таинства Евхаристии. Все православные христиане стараются причаститься Святых Христовых Таин. - В кафедральных соборах, в конце Литургии, совершается Чин умовения ног (архиерей умывает ноги 12 сослужителям).

- Вечером чтение 12-ти «Страстных Евангелий».

Патриарх совершает освящение мира. - Великая Пятница (14 апреля).

Арест Господа и неправедный суд. Распятие, Святые и Спасительные Страсти (Страдания), смерть и погребение Господа. - День великой скорби и строгого поста (Устав повелевает полное воздержание от пищи в течение всего дня; но, по традиции, воздерживаются от пищи до окончания выноса Плащаницы).

- Литургия (Бескровная Жертва) в этот день не служится, потому что Жертва принесена на Голгофе (единственное исключение – в случае совпадения Страстной Пятницы с праздником Благовещения).

- Утром – чтение Великих (Царских) Часов.

- В середине дня (обычно в 14 часов) совершается Чин выноса Плащаницы.

- Вечером (обычно в 18 часов) совершается Чин Погребения.

- Великая Суббота (15 апреля).

Пребывание Господа телом во гробе, сошествие душою во ад и одновременно пребывание на Престоле со Отцом и Святым Духом (см. Святая Троица). - Утром совершается Литургия Великой Субботы, после которой, по традиции, благословляется праздничная трапеза (Устав предписывает делать это после пасхальной Литургии и освящения артоса).

Светлое Христово Воскресение. Пасха – 16 апреля

Светлая седмица, сплошная (16–22 апреля).

Недели после Пасхи

- Антипасха (букв. «Вместо Пасхи»), иначе – Неделя 2‑я по Пасхе, апостола Фомы (Ин.20:19-31) – 23 апреля.

Радоница (пасхальное поминовение усопших) – 25 апреля, вторник. - Неделя 3‑я по Пасхе, святых жён-мироносиц (то есть «Неделя женщин, несущих миро»); и память праведных Никодима и Иосифа Аримафейского, тайных учеников Христа (Мк.15:43–16:8) – 30 апреля.

- Неделя 4‑я по Пасхе, о расслабленном (Ин.5:1-15) – 7 мая.

Преполовение Пятидесятницы (Ин.7:14-30) – 10 мая, среда. - Неделя 5‑я по Пасхе, о самарянке (Ин.4:5-42) – 14 мая.

- Неделя 6‑я по Пасхе, о слепом (Ин.9:1-38) – 21 мая.

- ВОЗНЕСЕНИЕ ГОСПОДНЕ (Деян.1:1-12; Лк.24:36-53) – 25 мая.

- Неделя 7‑я по Пасхе, святых отцов I Вселенского собора – 28 мая.

Троицкая родительская суббота (поминовение усопших) – 3 июня. - Неделя 8‑я по Пасхе. ДЕНЬ СВЯТОЙ ТРОИЦЫ (Пятидесятница) (Деян.2:1-11; Ин.7:37-52; 8:12) – 4 июня.

Седмица 1‑я по Пятидесятнице, сплошная (5–10 июня).

День Святого Духа («Духов День») – 5 июня, понедельник. - Неделя 1‑я по Пятидесятнице – праздник «Всех святых» – 11 июня. Этим праздником завершается собственно Триодный (подвижный) цикл; его своеобразным продолжением стал в русской традиции праздник в честь всех российских святых (установлен на Поместном соборе 1917–18 гг.). В конце XX столетия стали появляться праздники в честь региональных – сначала вологодских, а затем и других – святых.

***

Недели и особые дни поста: история и богослужение

Неделя о мытаре и фарисее

Самая поздняя по времени возникновения и утверждения в календаре из предварительных Недель Великого поста. Согласно константинопольскому Уставу, в воскресные дни от Недели по Воздвижении и до Великого поста читаются рядовые чтения из Евангелия от Луки. Некоторые из этих чтений были сознательно поставлены в конец цикла с тем расчетом, чтобы они были прочитаны в преддверии Великого поста (т.к. их содержание гармонирует с настроением подготовительного периода): это чтения о Закхее (Лк. 94-е зач.), причти о мытаре и фарисее (89‑е зач.) и блудном сыне (79‑е зач.). Впоследствии Неделя с чтением Евангелия о Закхее так и осталась без особого богослужения (в настоящее время это зачало читается всегда в последнее воскресенье перед Неделей о мытаре и фарисее), зато другие два чтения стали фундаментом для особых служб предварительного периода. Неделя о мытаре и фарисее появляется примерно в X -= XI вв., при этом первые сто лет ее положение как 4‑й Недели перед постом (если вести отсчет в обратном порядке) еще не было повсеместным (в евангелистариях XI века иногда встречается указание вставлять в воскресный день между Неделями о мытаре и фарисее и блудном сыне зачало о хананеянке — Мф. зач. 62‑е); лишь в XII веке Неделя о мытаре и фарисее уже получает фиксированное место — перед Неделей о блудном сыне.

Отмена поста в седмицу после Недели о мытаре и фарисее

Встречается утверждение, будто пост в эту седмицу отменяется с целью обличения поста евангельского фарисея. Однако этот тезис явно ошибочен; на самом деле правило отменять пост в эту седмицу появилось ранее, чем Неделя о мытаре и фарисее закрепилась на современном месте в календаре, и связано это правило с совсем другими причинами — политикой противодействия влиянию армян-монофизитов.

Дело вот в чем: в Армянской Церкви издревле существовал (и существует до сих пор) пятидневный пост, приходящийся на третью седмицу перед Великим постом (как раз седмица после Недели о мытаре и фарисее). Точных сведений о причинах и времени происхождения этого поста нет: армянская традиция возводит установление поста в IV веке к деятельности святителя Григория Великого, просветителя Армении, а несториане (которые также соблюдали этот пост) говорили, что пост был введен во 2‑й половине VI века вследствие эпидемии чумы как средство для умилостивления Бога. У армян пост получил название «араджаворац», что значит «передовой», то есть первый пост в календарном году. Этот пост соблюдается до сих пор https://old.armenianchurch.ru/religion/articles/fast/12192/

Сам «передовой» пост не имел догматической окраски. Однако из-за того, что армяне не приняли IV Вселенский Собор, византийцы с течением времени пост «араджаворац» стали воспринимать как еретическую особенность. Греческие церковные писатели резко осуждали эту практику поста, в результате чего появилось противоположное предписание — проводить всю седмицу после Недели о мытаре и фарисее как сплошную, не постясь в среду и пятницу. Впервые об этом обычае упоминает Никон Черногорец, писатель XI века. Скорее всего, изначально запрет поститься в среду и пятницу данной седмицы был адресован прежде всего тем христианам, которые жили в Палестине и Малой Азии (поэтому это предписание вошло в Иерусалимский Устав), то есть на территориях, близких к Армении и где жило много армян. Целью этого запрета было стремление решительно отмежеваться от инославных. Вследствие распространения Иерусалимского Устава на всем Востоке и становится практика отмены поста в 3‑ю седмицу перед Великим постом становится общецерковной. В нашем Типиконе описанная выше историческая причина кратко выражена в следующих словах: «Подобает ведати: яко в сей седмице иномудрствующии содержат пост, глаголемый арцивуриев. Мы же монаси на кийждо день, се же в среду и пяток, вкушаем сыр и яица, в 9‑й час. Миряне же ядят мясо, развращающе онех веление толикия ереси».

Неделя о блудном сыне

Появилась по тем же причинам, что и Неделя о мытаре и фарисее – как закрепление рядового чтения из Евангелия от Луки по причине его соответствия идее приготовления к Великому посту. Неделя о блудном сыне была добавлена в IX веке; некоторые сохранившиеся древнейшие Триоди начинаются с Недели о блудном сыне; точно так же Устав Великой церкви (IX в.) первым днем подвижного круга считает Неделю о блудном сыне, однако при этом именует ее «Неделей пред мясопустом». Это означает, что на ранней стадии эта Неделя еще не имела своего привычного современного названия.

Недели мясопустная и сыропустная

Появляются уже в VI веке; в это время в предпоследнее воскресенье пред постом заканчивали есть мясную пищу, а, соответственно, последнее воскресенье было днем заговения на молочную пищу. В древней иерусалимской традиции в VII веке эти два дня уже имели особые чтения на литургии, о чем мы узнаем из сохранившегося грузинского перевода Иерусалимского Лекционария. Правда, те иерусалимские чтения отличались от нынешних, ибо современные чтения возникли позднее в рамках константинопольской традиции.

Неделя 1‑я Великого поста — Торжество Православия

В современной службе Недели 1‑й Великого поста следует различать основную и второстепенную памяти. Основным празднованием является воспоминание Церковью восстановления иконопочитания в 843 году и окончательное отвержение иконоборческой ереси. В 842 году умер последний император-иконоборец Феофил и в этом же году был смещен с константинопольской кафедры Патриарх-иконоборец Иоанн Грамматик. Иконоборчество к этому времени уже изжило себя, да и принявшая власть по смерти Феофила его жена императрица Феодора еще при жизни мужа была сторонницей почитания икон. При ее поддержке началась подготовка к торжественному восстановлению иконопочитания, которая заняла около года; после того как в начале 843 года был избран Патриархом святитель Мефодий, в Константинополе впервые был совершен чин Торжества Православия. По стечению обстоятельств это произошло 11 марта 843 года, как раз в 1‑е воскресенье Великого поста (т.е. изначально не было стремления приурочить торжественное восстановление иконопочитания именно к 1‑й Неделе поста). Однако этот прецедент положил основание той многовековой традиции, которая сохраняется и в настоящее время: праздновать именно в Неделю 1‑ю Великого поста победу над иконоборчеством, с которой впоследствии была соединена идея торжества Церкви над всеми ересями вообще, потому этот день назван Торжество Православия.

Вскоре после 843 года была составлена нынешняя служба Недели Православия; в песнопениях службы основной акцент сделан на богословии иконопочитания. В частности, говорится о том, что именно Воплощение Христа является основой почитания Образа (кондак), что, целуя икону, мы воздаем честь тому, кто изображен на ней («честь бо образа, якоже глаголет Василий, на первообразное преходит», см. стихиру «Славы» на стиховне), раскрываются и другие аспекты церковного учения о почитании икон. Лишь на заключительном этапе развития Триоди память о торжестве иконопочитания была расширена к прославлению торжества Церкви над всеми лжеучениями. Так, во 2‑й стихире на стиховне малой вечерни упоминаются ересиархи прежних времен: «Ариева нечистая упразднися прелесть, Македониа, Петра, Севира же и Пирра: и светит Свет трисолнечный».

Второстепенной памятью Недели 1‑й поста в нынешнем Уставе является память всех святых пророков. До середины IX века (как минимум) в Константинополе именно память пророков совершали в 1‑й воскресный день Великого поста. В современной службе только пророкам посвящены следующие молитвословия: 1‑я и 2‑я стихиры на «Господи, воззвах…» великой вечерни, «славник» на литии, литургийные чтения и канон на повечерии в Неделю вечером..

Совершение Торжества Православия в Неделю 1‑ю поста не сразу вытеснило более древнюю память пророков. Решающее влияние в утверждении праздника Торжества Православия оказал Студийский Устав, во всех редакциях которого данная память уже присутствует. И эта связь закономерна: как Студийский монастырь был оплотом иконопочитания в период гонений императоров-иконоборцев, так он же способствовал распространению и возвышению праздника в честь восстановления почитания икон.

Интересными памятниками-свидетелями «переходного» периода в богослужении Недели 1‑й поста являются студийские Типиконы. В Студийско-Алексиевском Типиконе указаны обе памяти — пророков и «о иконах правоверия» (причем память пророков указана первой!), в соответствии с чем дается и схема песнопений: стихиры и канон пророкам присутствуют в службе наряду с песнопениями Торжества Православия. Это значит, что некоторое время обе памяти совершались вместе в 1‑ю Неделю поста, однако постепенно память пророков уходит в тень, а Торжество Православния занимает господствующее положение. Впрочем, до XIV века память пророков продолжает отмечаться в Типиконах и присутствует в службе Недели 1‑й Великого поста; в частности, она указана даже прежде Православия в одной из рукописей Иерусалимского Устава середины XIV века. Наверное, только с XVI века служба Недели 1‑й поста приобретает свой современный вид: песнопения Торжества Православия доминируют и почти совершенно вытесняют молитвословия в честь пророков (от этой древней памяти остаются только некоторые отмеченные нами песнопения, которые почти незаметны в службе), да и саму память пророков в Типиконе и Триоди перестают обозначать в надписании Недели.

Неделя 2‑я Великого поста – святителя Григория Паламы

Святитель Григорий Палама жил в XIV веке. Его особое значение в истории церкви связано с тем, что в споре с Варлаамом Калабрийским он отстоял православное учение о возможности для человека видения нетварных энергий Божества, то есть видения Самого Бога, а не Его тварного образа, как нечестиво учил Варлаам. Память святого в Неделю 2‑ю поста в Греции была установлена в 1376 году Патриархом Филофеем. Причина соединения прославления святителя Григория со 2‑й Неделей Великого поста очевидна: учение Варлаама в XIV веке рассматривали как одну из опаснейших ересей, и потому службу в честь святителя Григория, главного обличителя варлаамитов, постановили служить сразу после Недели Православия (чин которой к тому времени уже сформировался). Таким образом, если в Неделю 1‑ю мы празднуем торжество Церкви над всеми ересями в целом, то в Неделю 2‑ю эта тематика находит свое продолжение: здесь мы отмечаем победу над одной из опаснейших ересей позднего времени — учением Варлаама Калабрийского. Кроме этого, богословы находят в прославлении святителя Григория во 2‑ю Неделю поста еще и нравственно-аскетический аспект. Конечная цель любого аскетического делания (в том числе и настоящего поста), да и христианской жизни в целом — единение с Богом, встреча с Ним, возможность видеть Его славу своими телесными очами. Но это как раз тот аспект богословия, раскрытию которого посвятил свою жизнь святитель Григорий. В Русской Церкви службу святителю Григорию Паламе во 2‑ю Неделю Великого поста стали совершать только начиная с середины XVII века (до этого просто служили рядовом святому Минеи).

Неделя 3‑я Великого поста – Крестопоклонная

В константинопольском Месяцеслове был праздник перенесения частицы древа Креста из Апамеи в Константинополь, которое случилось при императоре Юстине (правда, источник не указывает, какой именно Юстин — Юстин I (518–527) или Юстин II (565–578) — имеется в виду). Так как согласно древнейшей традиции, в седмичные дни поста богослужения Минеи не совершались, то праздник Кресту сначала просто переносили на воскресные дни поста, а затем закрепили за 3‑й Неделей. Это закрепление произошло ранее IX века, так как составитель Триоди преподобный Феодор Студит сочинил канон для этой Недели, то есть в его время празднование Кресту в 3‑е воскресенье поста стало нормой. Кроме того, о поклонении Кресту в Неделю 3‑ю и во все дни 4‑й седмицы до пятницы включительно говорится во всех рукописях Устава Великой церкви, что также свидетельствует об утверждении этой памяти к IX веку. Таким образом, среди первых пяти Недель Великого поста в их современном виде именно Неделя 3‑я раньше всех других обрела свою индивидуальную память, которая празднуется доселе (тогда как памяти других Недель оформились позднее).

4‑я и 5‑я Недели поста – памяти преподобных Иоанна Лествичника и Марии Египетской

Принцип, лежащий в основе формирования этих подвижных памятей,— перенос праздников Минеи на субботние и воскресные дни. Память преподобного Иоанна по Минее приходится на 30 марта, а преподобной Марии — 1 апреля (интересно, что и в Минее эти святые находятся почти рядом, и в Триоди посвященные им Недели идут друг за другом). Память преподобной Марии связывается с 5‑й Неделей поста начиная с XI века, а память преподобного Иоанна появляется в рукописях только с XIV века, то есть гораздо позже. Интересным памятником промежуточного периода является Типикон константинопольского Евергетидского монастыря, датируемый концом XI века, в котором служба преподобной Марии уже есть, а службы преподобного Иоанна еще нет.

В русских старопечатных книгах обе памяти уже присутствовали, однако нетвердо: во-первых, самих песнопений святым в Триодях до середины XVII века не было (их предлагалось брать из Минеи), во-вторых, Устав предоставлял выбор настоятелю: служить ли службу преподобному или рядовому святому по Минее. Только после середины XVII века песнопения святым были внесены в Триодь, а их памяти окончательно закреплены за соответствующими Неделями.

Четверг 5‑й седмицы — Мариино стояние

Почему мы читаем канон в четверг 5‑й седмицы? С точки зрения исторической литургики ответить на поставленный вопрос можно лишь гипотетически (хотя с большой долей уверенности). В Византии в этот день богослужение было посвящено воспоминанию некоего землетрясения. Подтверждение этому тезису можно найти в некоторых молитвословиях дня: во-первых, на вечерне четверга в качестве паремии выбран фрагмент о гибели Содома, во-вторых, тропарь пророчества 6‑го часа («Благоутробне, Долготерпеливе Вседержителю Господи, низпосли милость Твою на люди Твоя») явно намекает на какое-то стихийное бедствие.

На вопрос о связи между памятью о землетрясении и чтением Великого канона отвечают так: во время константинопольского землетрясения Великий канон Андрея Критского стал употребляться, причем не как покаянный, а как богослужение бедствия, спасения, молитвы. Монахини монастыря Святого Патапия в Константинополе вышли на площадь, боясь быть погребенными под обломками, и стали читать этот покаянный канон. Получается, что сначала Великий канон был прочитан случайно во время землетрясения, а впоследствии стал ассоциироваться с памятью о землетрясении и потому его церковное употребление в первую очередь было соотнесено с тем днем, когда имело место богослужебное воспоминание землетрясения. Само землетрясение случилось 17 марта 790 года и долгое время в Месяцеслове Константинополя именно 17 марта было датой, в которую воспоминали землетрясение.

Возможно, что и чтение Великого канона сначала было закреплено за постоянной датой 17 марта. Действительно, Великий канон как покаянное произведение (образец покаяния) был оптимальным богослужебным текстом для такой памяти: землетрясение в библейском и христианском мировоззрении всегда воспринимается как суд Божий над грешным народом, потому и естественная реакция на это событие — покаяние.

Какое-то время память землетрясения «блуждала» по Триоди, выпадая на ее разные дни. Впоследствии служба Великого канона была закреплена на 5‑й седмице Великого поста в четверг. Это происходит только в XII–XIII веках.

Суббота 5‑я поста – Похвала Пресвятой Богородице

Первоначально Акафист пели на праздник Благовещения Пресвятой Богородице, причем здесь его пение, кроме догматической связи с праздником, получило историческую ассоциацию. Дело в том, что 24 марта 628 года начались переговоры императора Ираклия с персами о мире, чем был положен конец длительной, изнурительной военной кампании, завершившейся блистательной победой Византии. Потому пение Акафиста на праздник Благовещения Пресвятой Богородице имело значение благодарения за победу в этой грандиозной войне. Таким образом, установление ежегодного пения Акафиста имеет связь с событиями времен Ираклия (610–641), но это богослужебное действие соотносилось с победой в войне с персами в целом, а не с частным эпизодом данной войны (каким было спасение Константинополя). О пении Акафиста 25 марта говорят даже некоторые Минеи XII века, то есть эта традиция сохранялась довольно долго.

Вместе с тем появляется практика отделения Акафиста от праздника Благовещения, причем разные Уставы называют особые дни для Акафиста: 23 марта (Студийско-Алексиевский Типикон), вторник 6‑й седмицы (Триодь из лавры святителя Афанасия) или за 5 дней до Благовещения (итальянская версия Студийского Устава). Однако уже в X–XII веках наиболее популярным становится выбор 5‑й субботы Великого поста в качестве дня службы Акафиста, что зафиксировано во многих греческих и славянских Триодях (после XII в.).

Торжество Иерусалимского Устава, большинство рукописей которого относит пение Акафиста именно к субботе 5‑й седмицы, послужило окончательному закреплению праздника Похвалы Пресвятой Богородице за указанным днем. Однако до сих пор пение многих Благовещенских песнопений в субботу 5‑й седмицы Великого поста напоминает нам о древней связи этих двух празднований, и даже можно сказать, что событие Благовещения мы литургически вспоминаем дважды в году: в день самого праздника, то есть 25 марта, и в Субботу Акафиста.

6‑я Неделя поста – Неделя Ваий, Вход Господень в Иерусалим

Точное время возникновения праздника неизвестно, а самые ранние свидетельства о нем относятся к IV веку. Можно думать, что раньше всего праздник возник в Иерусалимской Церкви, то есть там, где и происходили сами воспоминаемые события. Паломница Эгерия описывает, что уже в IV веке в Иерусалиме отличительным моментом богослужения в этот день было шествие с горы Елеонской (т.е. тем путем, которым шел Господь) в Иерусалим, во время которого люди держали пальмовые ветви, а епископ ехал на осле. К этому же IV веку относится свидетельство святителя Амвросия Медиоланского о праздновании Входа Господня в Иерусалим в воскресенье перед Пасхой.

Однако большинство восточных и западных Церквей воспринимает этот праздник позднее. На Востоке повсеместным празднованием Входа Господа в Иерусалим становится лишь в конце V — начале VI века. Именно к этому времени относятся два свидетельства о празднике: Антиохийский Патриарх-монофизит Севир говорит, что на Востоке праздник Входа Господня стали праздновать около 500 года, а епископ Эдесский Петр, согласно одной из хроник, лично в это время ввел этот праздник в своей епархии. Что же касается Запада, то в IV–V веках празднование Входа Господня устанавливается во многих епархиях, кроме Римской. В Риме вплоть до VIII века последнее воскресение перед Пасхой было посвящено воспоминанию Страстей, так что праздник Входа Господня в Иерусалим там появился гораздо позже.

Интересно отметить, что в средние века в Константинополе существенной особенностью праздничного богослужения было шествие, в процессе которого Патриарх восседал на жеребце. На Руси также практиковался чин «хождения на осляти». Возник он сначала в Новгороде, где перед литургией совершали торжественный крестный ход, во время которого архиепископ ехал на «осляти» (коне, который был обряжен в осла), держа в левой руке Евангелие, а в правой — святой крест. С 1558 года этот чин стали совершать в Москве, где на осляти восседал Московский митрополит (впоследствии — Патриарх), символически изображавший Христа, а коня вели царь, «государев боярин» и «патриарший дворецкий».

Богослужение седмичных дней поста: особенности

В период Великого поста богослужения по особому чину (называемому великопостным) совершаются только в седмичные дни; в субботние и воскресные дни совершаются обычные службы.

Какие службы совершаются в седмичные дни поста?

На 1‑й седмице в течение пяти дней утром совершается весьма продолжительное богослужение, состоящее из утрени с 1‑м часом, 3‑го, 6‑го, 9‑го часов, изобразительных и вечерни (в среду и пятницу — литургия Преждеосвященных Даров). По вечерам с понедельника по четверг служится великое повечерие с Великим каноном преподобного Андрея Критского.

На остальных седмицах вечером совершается великое повечерие и утреня с 1‑м часом, а утром — 3‑й, 6‑й, 9‑й часы, изобразительны и вечерня (иногда в соединении с литургией Преждеосвященных Даров).

Накануне суббот во все седмицы (в том числе и в 1‑ю субботу поста,) совершаются великое повечерие (в 5‑ю субботу поста повечерие не служится) и утреня с 1‑м часом, в сами субботы — 3‑й и 6‑й час и литургия святителя Иоанна Златоуста.

Какие отличительные особенности имеет утреня?

- вместо «Бог Господь…» поется «Аллилуиа» с великопостными стихами, взятыми из 5‑й библейской песни (Ис. 26:9–19);

- после «Аллилуиа» вместо тропарей – троичны гласа;

- 3 кафизмы, после 1‑й кафизмы седальны из Октоиха (по факту из приложения Триоди), после 2‑й и 3‑й – из Триоди.

- Канон совершается с пением великопостных библейских песней; тропари – только из Минеи и Триоди (трипеснец). Есть примечательная особенность: 3‑я песнь кроме среды и 6‑я песнь всегда совершается без ирмоса (так как ирмос Минеи «уходит» на катавасию).

- По 6‑й песни канона в случае отсутствия кондака в Минее читается мученичен Октоиха

- По 9‑й песни поются великопостные светильны гласа.

- в конце утрени чтец читает следующие тексты: «Благо есть…» (дважды). Трисвятое по «Отче наш…». Возглас священника «Яко Твое есть Царство и сила и слава…». «Аминь. «В храме стояще…». «Господи, помилуй» (40 раз). «Слава, и ныне». «Честнейшую Херувим…». «Именем Господним…». Возглас: «Сый благословен Христос Бог наш…». «Аминь». «Небесный Царю…». Священник произносит молитву преподобного Ефрема Сирина («Господи и Владыко живота моего…») с 16‑ю поклонами. И сразу 1‑й час.

Чем великопостные часы отличаются от обычных вседневных часов?

Достаточно запомнить 6 основных отличий:

- Часы 3‑й, 6‑й и 9‑й совершаются вместе.

- На каждом часе читается кафисма, кроме 1‑го часа в понедельник и 1‑го и 9‑го часов в пятницу.

- Поется великопостный тропарь часа с поклонами (исключая праздники Благовещения Пресвятой Богородице и полиелейного святого в седмичный день, когда вместо великопостного тропаря читается тропарь праздника).

- По «Отче наш…» читаются особые тропари, текст которых дается в последовании часа (в Часослове или Следованной Псалтири) на ряду. Однако в праздники Благовещения Пресвятой Богородице и полиелейного святого в седмичный день вместо тропарей Часослова читается кондак праздника, а на седмице Крестопоклонной, в четверг 5‑й седмицы и в дни Страстной седмицы читается кондак Триоди.

- Перед молитвой часа совершается молитва преподобного Ефрема Сирина с 16‑ю (на 9‑м часе — с тремя) поклонами.

- На 6‑м часе после Богородична читаются тропарь пророчества, прокимен, паремия и второй прокимен.

Что можно сказать об изобразительных в седмичные дни поста?

Изобразительны начинаются с пения «Блаженн», в конце которых совершается 3 поклона. Далее тексты Часослова на ряду. По «Отче наш…» – кондаки по Уставу, переход на поклоны. После 16-ти поклонов два варианта:

А) если далее идет вечерня, то сразу вечерня без возгласа;

Б) если литургия Преждеосвященных Даров, то на изобразительных совершается отпуст.

Какие особенности имеет вечерня, совершаемая без литургии после изобразительных в понедельник, вторник и четверг?

- Начинается без возгласа «Благословен Бог наш…» сразу после поклонов на изобразительных;

- После «Свете тихий…» читается два прокимена и две паремии из Триоди (из книг Бытия и Притчей).

- По «Ныне отпущаеши…» — тропари «Богородице Дево, радуйся…», «Слава»: «Крестителю Христов…», «И ныне»: «Молите за ны…» с поклонами;

- Вместо сугубой ектении – «Господи, помилуй» 40 раз;

- В конце вечерни после 16-ти поклонов с молитвой преподобного Ефрема Сирина и конечного Трисвятого – молитва «Всесвятая Троице…», «Буди имя Господне…», 33 псалом.

Что такое «конечное Трисвятое» и когда оно читается?

«Конечным Трисвятым» Типикон называет добавляемую в окончание некоторых великопостных богослужений совокупность молитвословий от Трисвятого до «Отче наш..», с обязательным возгласом «Яко Твое есть Царство…» и чтением «Господи, помилуй» 12 раз (обратим внимание, что «Господи, помилуй» 12 раз всегда читается при конечном Трисвятом).

Конечное Трисвятое бывает, во-первых, только после 16-ти поклонов с молитвой преподобного Ефрема Сирина, во-вторых, только в окончании заключительного богослужения той или иной группы служб (другими словами, только на той службе, «которой оканчивается богослужебное собрание»).

Вот важнейшие случаи чтения «конечного Трисвятого»:

1) на 1‑м часе;

2) в конце одной из служб дневной группы (на практике совершаемых в первой половине дня):

а) на изобразительных в тех только случаях, когда они совершаются с отпустом и далее следует литургия Преждеосвященных Даров; если же после изобразительных следует только вечерня, то конечное Трисвятое не читается;

б) на вечерне, совершаемой в седмичные дни без соединения с литургией;

3) на великом повечерии (в 3‑й части) или на малом повечерии в Неделю вечером.

Таким образом, на практике «конечное Трисвятое» читается три раза в сутки: на 1‑м часе, на изобразительных или вечерне (только на одном из этих богослужений), и на повечерии. Кроме этого, Устав предусматривает чтение «конечного Трисвятого» в том случае, если в конце 6‑го часа творится отпуст и затем бывает пауза в богослужении, так что 9‑й час с вечерней совершаются в другое время (после полудня). Правда, в приходской практике подобный вариант не встречается.

Важно помнить, что «конечное Трисвятое» не читается во всех тех случаях, когда количество поклонов сокращается до трех (на Благовещение или в полиелейные праздники) или поклоны отменяются вовсе (на повечерии в пятницу вечером).

Что можно вкратце сказать об особенностях великого повечерия?

Великое повечерие состоит из 3‑х частей, каждая часть начинается «Приидите, поклонимся…». В 1‑й части примечательные следующие песнопения:

- Только на 1‑й седмице 4 дня в начале добавляется псалом 69 (переносится из 3‑й части) и далее поется великий канон преподобного Андрея Критского.

- После чтения 6‑ти псалмов поется «С нами Бог…»

- После Символа веры поется «Пресвятая Владычице…», в конце каждого стиха – земной поклон;

- В 3‑й части совершается молитва преподобного Ефрема Сирина с 1‑ю поклонами;

- Отпуст великого повечерия с преклонением колен и молитвой «Владыко Многомилостиве…»

Календарь Великого поста — для приходов, воскресных школ и дома — можно распечатать!

Версия календаря Великого поста для печати

Великий пост начинается за семь недель до Пасхи и состоит из четыредесятницы — сорока дней — и Страстной седмицы – недели перед самой Пасхой. Четыредесятница установлена в честь сорокодневного поста Спасителя, а Страстная седмица — в воспоминание последних дней земной жизни, страданий, смерти и погребения Христа. Общее продолжение Великого поста вместе со Страстной седмицей — 48 дней.

«Весна постная» — так называет Православная церковь время Великого поста, lent – (от древнеанглийского Lencten – весна) называется Великий пост в англоговорящих странах, напоминая о то, что пост – это время духовного расцвета и пробуждения.

Принято с особой строгостью соблюдать первую и Страстную седмицы Великого поста. Говорится в народе: «хорошее начало — половина дела». Видимо, поэтому многие христиане более строго постятся в первую неделю поста. Великий пост подразумевает исключение из рациона мясной, молочной, рыбной пищи и яиц, но меру своего поста надо обязательно согласовывать со священником, сообразуясь с состоянием здоровья.

В православных странах жизнь во время Великого поста кардинально менялась: закрывались театры, бани, игры, прекращалась торговля мясом, на первой неделе Поста и на Страстной седмице прекращались занятия в учебных заведениях, закрывались все государственные учреждения. По свидетельству историков, благочестивые люди на Руси в первые дни Великого поста без необходимости не выходили из своих домов. Царь Алексей Михайлович, царица и их взрослые дети в первые три дня поста соблюдали строгий пост, усердно посещали церковные службы. Только в среду после литургии Преждеосвященных Даров царь вкушал сладкий компот и рассылал его боярам. С четверга до субботы он снова постился, а в субботу причащался Святых Христовых Таин.

В Греции и сегодня первый день поста – выходной.

Первая седмица Великого поста отличается особенною строгостью, а Богослужение особенной продолжительностью.

прмч. Андрей Критский

В первые четыре дня (понедельник, вторник, среда и четверг) на Великом повечерии читается канон Св. Андрея Критского с припевами к стиху: «Помилуй меня, Боже, помилуй меня».

В этом каноне приводятся многочисленные примеры из Ветхого и Нового Завета, применительно к нравственному состоянию души человека, оплакивающего свои грехи, Канон назван великим как по множеству мыслей и воспоминаний, в нем заключенных, так и по количеству его тропарей (около 250, тогда как в обычных канонах их бывает около 30).

Православные всегда стараются не пропустить эти удивительные службы с чтением канона.

В пятницу первой седмицы Великого поста после Литургии происходит освящение «колива» т. е. отваренной пшеницы с медом, в память Св. Великомученика Феодора Тирона, оказавшего благотворную помощь христианам для сохранения поста.

В 362 году он явился епископу Антиохийскому Евдоксию и повелел ему сообщить христианам, чтобы они не покупали пищу, оскверненную идоложертвенной кровью императором Юлианом Отступником, но употребляли бы коливо (отваренные зерна пшеницы).

Спас на престоле с припадающим митрополитом Киприаном

В первое воскресенье (Неделю) Великого поста совершается так называемое «Торжество православия», установленное при царице Феодоре в 842 году в память восстановления почитания святых икон.

Во время этого праздника выставляются, в середине храма полукругом, на аналоях (высокие столики для икон) храмовые иконы. В конце Литургии священнослужители совершают молебное пение на середине храма перед иконами Спасителя и Божьей Матери, молясь Господу об утверждении в вере православных христиан и обращение на путь истинный всех отступивших от Церкви.

Святитель Григорий Палама, архиепископ Фессалонитский

Во второе воскресенье Великого поста совершается память св. Григория Паламы, жившего в 14 веке.

Согласно православной вере, он учил, что за подвиг поста и молитвы Господь озаряет верующих Своим благодатным светом, каким сиял Господь на Фаворе. По той причине, что св. Григорий раскрыл учение о силе поста и молитвы, и установлено совершать его память во второе воскресенье Великого поста.

Поклонение Кресту

В третье воскресенье Великого поста за Всенощной выносится Святой Крест. Все верующие поклоняются Кресту, в это время поется: «Кресту Твоему покланяемся, Владыко, и святое воскресение Твое славим».

Церковь выставляет в середине Четыредесятницы верующим Крест для того, чтобы напоминанием о страданиях и смерти Господней укрепить постящихся к продолжению подвига поста. Св. Крест остается для поклонения в течение недели до пятницы. Поэтому третье воскресенье и четвертая седмица Великого поста называются «крестопоклонными».

прп. Иоанн Лествичник

В четвертое воскресенье вспоминается великий подвижник VI века – святой Иоанн Лествичник, который с 17 до 60 лет подвизался на Синайской горе, и в своем творении «Лествица Рая» изобразил путь постепенного восхождения человека к духовному совершенствованию, как по лестнице, возводящей от земли к вечно пребывающей славе.

Св. прп. Мария Египетская

В четверг на пятой неделе совершается так называемое «стояние Св. Марии Египетской». Жизнь Св. Марии Египетской – великой грешницы, которая смогла искренне покаяться в совершенных грехах и долгие годы провела в пустыне в покаянии – должна убеждать всех в неизреченном милосердии Божьем.

В субботу на пятой неделе совершается «Похвала Пресвятой Богородице»: читается великий акафист Богородице. Эта служба установлена в Греции в благодарность Богородице за неоднократное избавление Ею Царьграда от врагов.

В пятое воскресенье Великого Поста совершается последование преподобной Марии Египетской.

В субботу на 6-ой неделе на Утрене и Литургии вспоминается воскрешение Иисусом Христом Лазаря.

Вход Господень в Иерусалим.

Шестое воскресенье Великого Поста – великий двунадесятый праздник, в который празднуется торжественный вход Господень в Иерусалим на вольные страдания.

Этот праздник иначе называется Вербным воскресением, Неделею Вайи и Цветоносною. На Всенощной освящаются молитвой и окроплением святой воды распускающиеся ветви вербы (вайа) или других растений. Освященные ветви раздаются молящимся, с которыми, при зажженных свечах, верующие стоят до конца службы, знаменуя победу жизни над смертью (воскресение).

Вербным Воскресеньем заканчивается четыредесятница и наступает Страстная Седмица.

Во время Великого Поста в церкви и дома читается покаянная молитва святого Ефрема Сирина:

Господи и Владыко живота моего, дух праздности, уныния, любоначалия и празднословия не даждь ми.

(Земной поклон).

Дух же целомудрия, смиренномудрия, терпения и любве, даруй ми рабу Твоему.

(Земной поклон).

Ей, Господи Царю, даруй ми зрети моя прегрешения, и не осуждати брата моего, яко благословен еси во веки веков, аминь.

(Земной поклон).

Боже, очисти мя грешного.

(12 раз и столько же поясных поклонов).

(Потом повторить всю молитву):

Господи и Владыко живота ……. во веки веков, аминь.

(и один земной поклон).

Три субботы — второй, третьей и четвертой недель Великого поста установлены для поминовения усопших: Великопостные родительские субботы.

Читайте также:

|

|

|

|

10 правил Великого поста

Мария Сеньчукова Чтобы провести Великий пост с Господом и Его учениками, а не превратить его в полтора месяца тяжелой и бессмысленной диеты, следует придерживаться нескольких важных правил. |

|

|

|

|

Календарь Великого поста

Мария Сеньчукова Когда следует особенно строго поститься в дни Святой Четыредесятницы? Как правильно вести себя на Страстной неделе? На каких службах необходимо побывать? |

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

This article is about the Western Christian 40-day period. For Lent in Eastern Christianity, see Great Lent. For other uses, see Lent (disambiguation).

| Lent Quadragesima |

|

|---|---|

High altar, barren, with few adornments, as is custom during Lent |

|

| Type | Christian |

| Celebrations |

|

| Observances |

|

| Begins |

|

| Ends |

|

| Date | Variable (follows the paschal computus, and depends on denomination) |

| 2022 date |

|

| 2023 date |

|

| 2024 date |

|

| Frequency | Annual (lunar calendar) |

| Related to | Exodus, Temptation of Christ |

Lent (Latin: Quadragesima,[1] ‘Fortieth’) is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, before beginning his public ministry.[2][3] Lent is observed in the Anglican, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Methodist, Moravian, Oriental Orthodox, Persian, United Protestant and Roman Catholic traditions.[4][5] Some Anabaptist, Baptist, Reformed (including certain Continental Reformed, Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches), and nondenominational Christian churches also observe Lent, although many churches in these traditions do not.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

Which days are enumerated as being part of Lent differs between denominations (see below), although in all of them Lent is described as lasting for a total duration of 40 days. In Lent-observing Western Churches, Lent begins on Ash Wednesday and ends approximately six weeks later; depending on the Christian denomination and local custom, Lent concludes either on the evening of Maundy Thursday,[12] or at sundown on Holy Saturday, when the Easter Vigil is celebrated,[13] though in either case, Lenten fasting observances are maintained until the evening of Holy Saturday.[14] Sundays may or may not be excluded, depending on the denomination. In Eastern Churches (whether Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Lutheran, or Eastern Catholic), Lent is observed continuously without interruption for 40 days starting on Clean Monday and ending on Lazarus Saturday before Holy Week.[15][16]

Lent is a period of grief that necessarily ends with a great celebration of Easter. Thus, it is known in Eastern Orthodox circles as the season of «bright sadness» (Greek: χαρμολύπη, romanized: charmolypê).[17] The purpose of Lent is the preparation of the believer for Easter through prayer, mortifying the flesh, repentance of sins, almsgiving, simple living, and self-denial.[18] In Lent, many Christians commit to fasting, as well as giving up certain luxuries in imitation of Jesus Christ’s sacrifice during his journey into the desert for 40 days;[19][20][21] this is known as one’s Lenten sacrifice.[22]

Many Lent-observing Christians also add a Lenten spiritual discipline, such as reading a daily devotional or praying through a Lenten calendar, to draw themselves near to God.[23][24] Often observed are the Stations of the Cross, a devotional commemoration of Christ’s carrying the Cross and crucifixion. Many churches remove flowers from their altars and veil crucifixes, religious statues that show the triumphant Christ, and other elaborate religious symbols in violet fabrics in solemn observance of the event. The custom of veiling is typically practiced the last two weeks, beginning on the Sunday Judica which is therefore in the vernacular called Passion Sunday until Good Friday, when the cross is unveiled solemnly in the liturgy.

In most Lent-observing denominations, the last week of Lent coincides with Holy Week, starting with Palm Sunday. Following the New Testament narrative, Jesus’ crucifixion is commemorated on Good Friday, and at the beginning of the next week the joyful celebration of Easter Sunday, the start of the Easter season, which recalls the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. In some Christian denominations, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday form the Easter Triduum.[25]

Etymology[edit]

The English word Lent is a shortened form of the Old English word lencten, meaning «spring season», as its Dutch language cognate lente (Old Dutch lentin)[27] still does today. A dated term in German, Lenz (Old High German lenzo), is also related. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘the shorter form (? Old Germanic type *laŋgito— , *laŋgiton-) seems to be a derivative of *laŋgo— long […] and may possibly have reference to the lengthening of the days as characterizing the season of spring’. The origin of the —en element is less clear: it may simply be a suffix, or lencten may originally have been a compound of *laŋgo— ‘long’ and an otherwise little-attested word *-tino, meaning «day».[20]

In languages spoken where Christianity was earlier established, such as Greek and Latin, the term signifies the period dating from the 40th weekday before Easter. In modern Greek the term is Σαρακοστή (Sarakostí), derived from the earlier Τεσσαρακοστή (Tessarakostí), meaning «fortieth». The corresponding word in Latin, quadragesima («fortieth»), is the origin of the terms used in Latin-derived languages and in some others. Examples in the Romance language group are: Catalan quaresma, French carême, Galician coresma, Italian quaresima, Occitan quaresma, Portuguese quaresma, Romanian păresimi, Sardinian caresima, Spanish cuaresma, and Walloon cwareme.[1] Examples in non-Latin-based languages are: Albanian kreshma, Basque garizuma, Croatian korizma, Irish and Scottish Gaelic carghas, Swahili kwaresima, Filipino kuwaresma, and Welsh c(a)rawys.[citation needed]

In other languages, the name used refers to the activity associated with the season. Thus it is called «fasting period» in Czech (postní doba), German (Fastenzeit), and Norwegian (fasten/fastetid), and it is called «great fast» in Arabic (الصوم الكبير – al-ṣawm al-kabīr, literally, «the Great Fast»), Polish (wielki post), Russian (великий пост – vieliki post), and Ukrainian (великий піст – velyky pist). Romanian, apart from a version based on the Latin term referring to the 40 days (see above), also has a «great fast» version: postul mare. Dutch has three options, one of which means fasting period, and the other two referring to the 40-day period indicated in the Latin term: vastentijd, veertigdagentijd and quadragesima, respectively.[1]

Origin[edit]

Early Christianity records the tradition of fasting before Easter.[28] The Apostolic Constitutions permit the consumption of «bread, vegetables, salt and water, in Lent» with «flesh and wine being forbidden.»[28] The Canons of Hippolytus authorize only bread and salt to be consumed during Holy Week.[28] The practice of fasting and abstaining from alcohol, meat and lacticinia during Lent thus became established in the Church.[28]

In AD 339, Athanasius of Alexandria wrote that the Lenten fast was a forty-day fast that «the entire world» observed.[29] Saint Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–AD 430) wrote that: «Our fast at any other time is voluntary; but during Lent, we sin if we do not fast.»[30]

Three main prevailing theories exist on the finalization of Lent as a forty-day fast prior to the arrival of Easter Sunday: First, that it was created at the Council of Nicea in 325 and there is no earlier incarnation. Second, that it is based on an Egyptian Christian post-theophany fast. Third, a combination of origins syncretized around the Council of Nicea.[31] There are early references to periods of fasting prior to baptism. For instance, the Didache, a 1st or 2nd-century Christian text, commends «the baptizer, the one to be baptized, and any others that are able» to fast to prepare for the sacrament.[32] For centuries it has been common practice for baptisms to take place on Easter, and so such references were formerly taken to be references to a pre-Easter fast. Tertullian, in his 3rd-century work On Baptism, indicates that Easter was a «most solemn day for baptism.» However, he is one of only a handful of writers in the ante-Nicene period who indicates this preference, and even he says that Easter was by no means the only favored day for baptisms in his locale.[33] Since the 20th century, scholars have acknowledged that Easter was not the standard day for baptisms in the early church, and references to pre-baptismal periods of fasting were not necessarily connected with Easter. There were shorter periods of fasting observed in the pre-Nicene church (Athanasius noted that the 4th-century Alexandrian church observed a period of fasting before Pascha [Easter]).[31] However it is known that the 40-day period of fasting – the season later named Lent – before Eastertide was clarified at the Nicene Council.[34] In 363-64 AD, the Council of Laodicea prescribed the Lenten fast as «as of strict necessity.»[29]

Date and duration[edit]

Some named days and day ranges around Lent and Easter in Western Christianity, with the fasting days of Lent numbered

The 40 days of Lent are calculated differently among the various Christian denominations that observe it, depending on how the date of Easter is calculated, but also on which days Lent is understood to begin and end, and on whether all the days of Lent are counted consecutively. Additionally, the date of Lent may depend on the calendar used by the particular church, such as the (revised) Julian or Gregorian calendars typically used by Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox churches, or the Ethiopian and Coptic calendars traditionally used by some Oriental Orthodox churches.

Roman Catholicism[edit]

Since 1970, in the Roman Rite Lent starts on Ash Wednesday and ends on the evening of Maundy Thursday with the Mass of the Lord’s Supper. This comprises a period of 44 days. The Lenten fast excludes Sundays and continues through Good Friday and Holy Saturday, totaling 40 days (though the Eucharistic Fast still applies).[35][36] Although Lent may formally end on Maundy Thursday, Lenten fasting practices continue until the Easter Vigil and additionally, the celebration of Easter is preceded by the Paschal fast.[14][37]

In the Ambrosian Rite, Lent begins on the Sunday that follows what is celebrated as Ash Wednesday in the rest of the Latin Catholic Church, and ends as in the Roman Rite, thus being of 40 days, counting the Sundays but not Maundy Thursday. The day for beginning the Lenten fast in the Ambrosian Rite is the Monday after Ash Wednesday. The special Ash Wednesday fast is transferred to the first Friday of the Ambrosian Lent. Until this rite was revised by Saint Charles Borromeo, the liturgy of the First Sunday of Lent was festive, celebrated in white vestments with chanting of the Gloria in Excelsis and Alleluia, in line with the recommendation in Matthew 6:16, «When you fast, do not look gloomy.»[38][39][40]

During Lent, the Church discourages marriages, but couples may marry if they forgo the special blessings of the Nuptial Mass and limit social celebrations.[41]

The period of Lent observed in the Eastern Catholic Churches corresponds to that in other churches of Eastern Christianity that have similar traditions.

Protestantism and Western Orthodoxy[edit]

In Western traditions, the liturgical colour of the season of Lent is purple. Altar crosses and religious statuary which show Christ in his glory are traditionally veiled during this period in the Christian year.

In Protestant and Western Orthodox Churches that celebrate it, the season of Lent lasts from Ash Wednesday to the evening of Holy Saturday.[16][42] This calculation makes Lent last 46 days if the 6 Sundays are included, but only 40 days if they are excluded.[43] This definition is still that of the Moravian Church,[44] Lutheran Church,[45] Anglican Church,[46] Methodist Church,[13] Western Rite Orthodox Church,[47] United Protestant Churches,[48] and those of the Reformed Churches (i.e., Continental Reformed, Presbyterian, and Congregationalist) that observe Lent.[49][50]

Eastern Orthodoxy and Byzantine Rite[edit]

In the Byzantine Rite, i.e., the Eastern Orthodox Great Lent (Greek: Μεγάλη Τεσσαρακοστή or Μεγάλη Νηστεία, meaning «Great 40 Days» and «Great Fast» respectively) is the most important fasting season in the church year.[51]

The 40 days of Great Lent include Sundays, and begin on Clean Monday. The 40 days are immediately followed by what are considered distinct periods of fasting, Lazarus Saturday and Palm Sunday, which in turn are followed straightway by Holy Week. Great Lent is broken only after the Paschal (Easter) Divine Liturgy.

The Eastern Orthodox Church maintains the traditional Church’s teaching on fasting. The rules for lenten fasting are the monastic rules. Fasting in the Orthodox Church is more than simply abstaining from certain foods. During the Great Lent Orthodox Faithful intensify their prayers and spiritual exercises, go to church services more often, study the Scriptures and the works of the Church Fathers in depth, limit their entertainment and spendings and focus on charity and good works.

Oriental Orthodoxy[edit]

Among the Oriental Orthodox, there are various local traditions regarding Lent. Those using the Alexandrian Rite, i.e., the Coptic Orthodox, Coptic Catholic, Ethiopian Orthodox, Ethiopian Catholic, Eritrean Orthodox, and Eritrean Catholic Churches, observe eight continuous weeks of fasting constituting three distinct consecutive fasting periods:

- a Pre-Lenten fast in preparation for Great Lent

- Great Lent itself

- the Paschal fast during Holy Week which immediately follows Lent

As in the Eastern Orthodox Churches, the date of Easter is typically reckoned according to the Julian Calendar, and usually occurs later than Easter according to Gregorian Calendar used by Catholic and Protestant Churches.

Ethiopian Orthodoxy[edit]

In Ethiopian Orthodoxy, fasting (tsome) lasts for 55 continuous days before Easter (Fasika), although the fast is divided into three separate periods: Tsome Hirkal, the eight-day Fast of Heraclius, commemorating the fast requested by the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius before he reputedly set out to fight the Sassanian Empire and recover the True Cross which had been seized and taken from Jerusalem; Tsome Arba, 40 days of Lent; and Tsome Himamat, seven days commemorating Holy Week.[52][53][54] Fasting involves abstention from animal products (meat, dairy, and eggs), and refraining from eating or drinking before 3:00 pm.[52] Ethiopian devotees may also abstain from sexual activity and the consumption of alcohol.[52]

Quartodecimanism[edit]

Quartodeciman Christians end the fast of Lent on the Paschal full moon of the Hebrew calendar, in order to celebrate the Feast of Unleavened Bread beginning on the 14th of Nisan, whence the name derives. For this practice, they were excommunicated in the Easter controversy of the 2nd century A.D.

Associated customs[edit]

Three traditional practices to be taken up with renewed vigour during Lent; these are known as the three pillars of Lent:[55]

- prayer (justice toward God)

- fasting (justice toward self)

- almsgiving (justice toward neighbours)

Self-reflection, simplicity, and sincerity (honesty) are emphasised during the Lenten season.[18]

Pre-Lenten observances[edit]

Shrovetide[edit]

During the season of Shrovetide, it is customary for Christians to ponder what Lenten sacrifices they will make for Lent.[56] Another hallmark of Shrovetide is the opportunity for a last round of merrymaking associated with Carnival and Fastelavn before the start of the somber Lenten season; the traditions of carrying Shrovetide rods and consuming Shrovetide buns after attending church is celebrated.[57][58] On the final day of the season, Shrove Tuesday, many traditional Christians, such as Lutherans, Anglicans, Methodists and Roman Catholics, «make a special point of self-examination, of considering what wrongs they need to repent, and what amendments of life or areas of spiritual growth they especially need to ask God’s help in dealing with.»[59][60] During Shrovetide, many churches place a basket in the narthex to collect the previous year’s Holy Week palm branches that were blessed and distributed during the Palm Sunday liturgies; on Shrove Tuesday, churches burn these palms to make the ashes used during the services held on the very next day, Ash Wednesday.[61]

In historically Lutheran nations, Shrovetide is known as Fastelavn. After attending the Mass on Shrove Sunday, congregants enjoy Shrovetide buns (fastelavnsboller), «round sweet buns that are covered with icing and filled with cream and/or jam.»[57] Children often dress up and collect money from people while singing.[57] They also practice the tradition of hitting a barrel, which represents fighting Satan; after doing this, children enjoy the sweets inside the barrel.[57] Lutheran Christians in these nations carry Shrovetide rods (fastelavnsris), which «branches decorated with sweets, little presents, etc., that are used to decorate the home or give to children.»[57]

In English-speaking countries such as the United Kingdom and Canada, the day before Lent is known as Shrove Tuesday, which is derived from the word shrive, meaning «to administer the sacrament of confession to; to absolve.»[62] In these countries, pancakes are associated with Shrove Tuesday because they are a way to use up rich foods such as eggs, milk, and sugar – rich foods which are not eaten during the season.[63]

Mardi Gras and carnival celebrations[edit]

Mardi Gras («Fat Tuesday») refers to events of the Carnival celebration, beginning on or after the feast of Epiphany and culminating on the day before Lent.[64] The carnival celebrations which in many cultures traditionally precede Lent are seen as a last opportunity for excess before Lent begins. Some of the most famous are the Carnival of Barranquilla, the Carnival of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, the Carnival of Venice, Cologne Carnival, the New Orleans Mardi Gras, the Rio de Janeiro carnival, and the Trinidad and Tobago Carnival.[citation needed]

Pre-Lenten fasting[edit]

In stark contrast to traditions of merrymaking and feasting, Oriental Orthodox Churches practice a Pre-Lenten fast in preparation for Lent which is immediately followed by the fast of Great Lent without interruption.

Fasting and Lenten sacrifice[edit]

There are traditionally 40 days in Lent; these are marked by fasting, both from foods and festivities, and by other acts of penance. Fasting is maintained for all forty days of Lent (regardless of how they are enumerated; see above). Historically, fasting has been maintained continuously for the whole Lenten season, including Sundays. The making of a Lenten sacrifice, in which Christians give up a personal pleasure for the duration of 40 days, is a traditional practice during Lent.[65]

During Shrovetide and especially on Shrove Tuesday, the day before the start of the Lenten season, many Christians finalize their decision with respect to what Lenten sacrifices they will make for Lent.[56] Examples include practicing vegetarianism and teetotalism during Lent as a Lenten sacrifice.[66][67] While making a Lenten sacrifice, it is customary to pray for strength to keep it; many often wish others for doing so as well, e.g. «May God bless your Lenten sacrifice.»[68] In addition, some believers add a regular spiritual discipline, to bring them closer to God, such as reading a Lenten daily devotional.[23]

For Lutherans, Moravians, Anglicans, Methodists, Roman Catholics, United Protestants, and Lent-observing Reformed Christians, the Lenten penitential season ends after the Easter Vigil Mass or Sunrise service. Orthodox Christians also break their fast after the Paschal Vigil, a service which starts around 11:00 pm on Holy Saturday, and which includes the Paschal celebration of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. At the end of the service, the priest blesses cheese, eggs, flesh meats, and other items that the faithful have been abstaining from for the duration of Great Lent.

Lenten traditions and liturgical practices are less common, less binding, and sometimes non-existent among some liberal and progressive Christians.[69] A greater emphasis on anticipation of Easter Sunday is often encouraged more than the penitence of Lent or Holy Week.[70]

Some Christians as well as secular groups also interpret the Lenten fast in a positive tone, not as renunciation but as contributing to causes such as environmental stewardship and improvement of health.[71][72] Even some atheists find value in the Christian tradition and observe Lent.[73]