Рассмотрим самые распространенные виды и стили мужской и женской одежды родины самураев.

Национальная одежда Японии

Кимоно

Кимоно является традиционной одеждой Японии и представляет собой длинный халат с широкими рукавами, который стягивается на талии поясом оби. На кимоно присутствуют многочисленные ремешки и шнуры. Отличие женского кимоно от мужского состоит в том, что халат японской женщины состоит из 12 частей, и надеть его самостоятельно практически невозможно. Кимоно же мужчины более простое, из пяти элементов и с коротким рукавом.

Кимоно заправляют слева направо, исключение составляют похороны – на них заправка идет в обратной последовательности. Настоящее японское кимоно имеет высокую цену – от десяти тысяч долларов в базовой комплектации, а со всеми аксессуарами около двадцати тысяч.

Оби

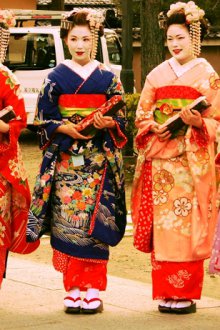

Оби – японский пояс, которым стягивали кимоно и кэйкоги. Мужской пояс десять сантиметров в ширину и длиной около трех метров, женский пояс намного больше и длиннее – более 30 сантиметров в ширину и четырех метров в длину. Оби, который носили гейши и вовсе огромен – метровой ширины. Оби обматывают несколько раз вокруг талии и затягивают на нижней части спины бантом. Спереди оби завязывают не только юдзё — японские проститутки, как ошибочно принято считать, но и замужние женщины.

Юката

Юката – легкое кимоно из хлопка или льна без подкладки, носится на улице летом, в домашней обстановке или после принятия водных процедур. Юката одевается как мужчинами, так и женщинами.

Кэйкоги

Кэйкоги – костюм, состоящий из рубахи и свободных штанов, надевается при занятиях японскими боевыми искусствами – айкидо, дзюдо и т.д. Часто его называют кимоно, что неправильно.

Таби и гэта

Таби – японские традиционные носки, в которых большой палец отделен от остальных и просунут в специальное отделение. Являются неотъемлемой частью национального японского костюма и надеваются под сандалии гэта и дзори.

Гэта – японские традиционные сандалии с высокой деревянной подошвой, закрепляются с помощью шнурков или ремешков, которые идут от пятки к носку и проходят в щель между большим и средним пальцами.

Таби и гэта

Хакама

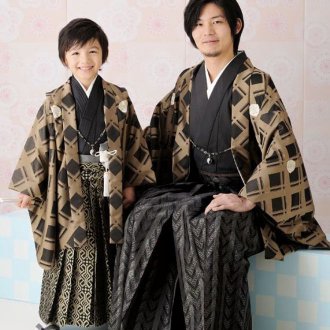

Хакама — в древние времена в Японии так называли ткань, которой обвивали бедра, затем очень широкие складчатые штаны, которые имели право носить только самураи и монахи. Обычным людям носить этот вид одежды можно было лишь в очень значимые праздники.

Красное хакама с белым кимоно является женской религиозной одеждой синто.

Кроме того, штаны хакама красной окраски носили женщины аристократического происхождения вместе с дзюни-хитоэ – одеянием, которое включало в себя несколько шелковых кимоно, надетых друг на друга.

Большое распространение хакама получили в различных видах боевых искусств.

Видео по теме

В видео рассказывается, как надеть традиционное японское кимоно и завязать пояс оби.

Жанр статьи — Одежда Японии

Кимоно — это традиционное японское одеяние, которое носили до тех пор, пока в период Мэйдзи не появилась западная культура и одежда.

Коренное население Японии, древние айны, носили Т-образный халат, простой и довольно короткий. Он был удобен и не стеснял движение. Древние японцы, переселившись на острова с Корейского полуострова, частично переняли традиции у айнов. Влияние оказал и китайский халат ханьфу.

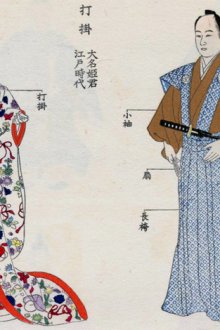

Считается, что нынешний стиль кимоно сформировался в период Эдо. В течение этого периода кимоно развивалось различными способами, менялась покраска, способы вышивки и ткачества, чтобы удовлетворить потребности клиентов, особенно в плане украшения. С приходом западной одежды в эпоху Мэйдзи (1868-1912) кимоно постепенно превратилось в одежду, которую стали надевали в особых случаях.

Кимоно и пояс оби изготавливаются из самых разных типов волокон, включая коноплю, лен, шелк, креп. После открытия границ Японии в начале периода Мэйдзи стали популярными материалы, такие как шерсть и использование синтетических красителей. А искусственный шелк, получил широкое распространение во время Второй мировой войны, будучи недорогим в производстве и дешевыми в покупке. Современные кимоно широко доступны из тканей, которые считаются более простыми в уходе, например из полиэстера.

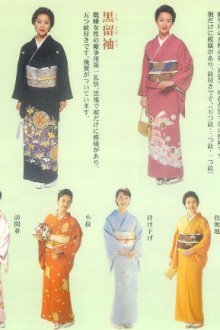

Виды кимоно

Куротомэсодэ (黒留袖)

Черное кимоно с рисунком только ниже талии. Самое формальное и элегантное кимоно, которое замужние женщины носят только по торжественным случаям, например, свадьба родственника. Кимоно имеет пять узоров семейного герба, передаваемого по наследству.

Фурисодэ (振袖)

Официальное платье для незамужних женщин, которое часто можно увидеть на церемониях совершеннолетия. Его можно носить на выпускных церемониях и даже в официальных случаях, таких как свадьбы. Основные характеристики этого кимоно — длинные рукава, которые в среднем составляют 100–110 см.

Иротомэсодэ (色留袖)

В последние годы иротомэсодэ был официальной одеждой для женщин, независимо от того, замужем они или нет. Это кимоно надевают на праздники. Орнамент только по подолу, но в отличие от куротомэсодэ, бывает разных цветов, таких как нежно-розовый, ярко-зеленый и холодный синий, чтобы привнести «цвета» в такие счастливые события, как свадьбы.

Хоумонги (訪問着)

Хоумонги и иротомэсодэ выглядят похожими, однако основное различие заключается в том, есть ли узор на верхней половине тела. Для Хоумонги характерны ниспадающие с плеч узоры, спускающиеся вниз по рукавам и боковым швам. Это полуформальный наряд, который носят женщины независимо от того, замужем они или нет и надевают на свадьбах и официальных мероприятиях.

Цукесагэ (付け下げ)

Это кимоно обладает более сдержанным и скромным рисунком по сравнению с Хоумонги и в основном рисунок расположен ниже талии. Это кимоно могут так же носить все женщины.

Иромудзи (色無地)

Однотонное кимоно без рисунков. Как правило, оно надевается на чайную церемонию.

Комон (小紋)

Характеризуется мелким повторяющимся узором. Носится в повседневности, для прогулок по городу или в ресторан.

Сусохики (裾引き)

Кимоно для гейш и исполнительниц традиционных танцев. Его отличает наличие шлейфа.

Мофуку (喪服)

Траурное кимоно для похорон, полностью черное. Может иметь только герб семьи.

Юката (浴衣)

Тип тонкого кимоно, которое носят летом. Его можно носить дома или для короткой прогулки по местности, надевают на фестивали или чтобы пойти посмотреть фейерверк.

Сезонные расцветки

Кимоно бывают разных цветов и узоров, и ношение подходящего для сезона всегда было частью японской культуры. Материал и пошив кимоно меняются в зависимости от сезона, например, толстая ткань на подкладке зимой и легкая прозрачная ткань летом.

Весна

Кимоно пастельных тонов, особенно розового, — подходящий цвет для весенней одежды.

Узоры сакуры — это основной продукт весны, и их обычно носят с конца зимы до конца марта, когда цветы все еще находятся в третьем цветении. Ношение кимоно с рисунком цветущей сакуры, когда цветы уже полностью распустились, создает впечатление, что кимоно конкурирует с настоящей вишней и не сможет выделяться, поэтому носить уже не рекомендуется. Вместо этого, когда цветы сакуры уже распустились, лучше носить кимоно с глицинией или пионом. Кроме того, из-за красивого рисунка многие склонны выбирать его независимо от сезона, однако этот рисунок считается сезонным, но его можно носить только в течение ограниченной ранней весны. Из этого правила есть исключение, и если вишни изображены с другими сезонными цветами, такими как осенние листья, кленовые листья или хризантемы, или нарисованы не реалистично, их можно носить круглый год.

Глицинии полностью цветут с апреля по май в зависимости от сорта. Кимоно с рисунком глицинии обычно надевают с конца марта по апрель, начиная примерно с того времени, когда цветет вишня. Поскольку грозди цветов глицинии выглядят как колосья риса, есть примета, что цветы глицинии символизируют желание хорошего урожая.

Крупные цветы пиона были популярным узором с древних времен. Пионы часто используются для праздничных мероприятий, формальной одежды и Фурисодэ, и будто создает ощущение гламура. Весенние пионы цветут с апреля по май, а зимние пионы — с января по февраль, поэтому, если это изображено абстрактно в сочетании с другими узорами, то кимоно с рисунком пионов можно носить в любое время года.

Лето

Уже в середине июня и не позднее июля кимоно заменяют юката. Светлые бледные и холодные цвета, которые выглядят прохладно в жаркие летние месяцы, являются самыми популярными цветами, которые выбирают многие в это время года.

В японском языке есть термин, который описывает воплощение чистой женской красоты, известный как Ямато Надэсико. Считается, что этот термин произошел от цветка японского диантуса (гвоздика), который по-японски называется 大和撫子. Этот цветок довольно часто используют в качестве узора для юката и надевают в период с июля по август, чтобы подчеркнуть такую «элегантную» внутреннюю красоту женщины, как и его цветок.

Гортензия — это цветок, родом из Японии, который с древних времен использовался во многих узорах юката и кимоно. Поскольку они цветут в сезон дождей, отдельные узоры часто носят летом, примерно в июне и июле.

Осень

Как правило, юката можно носить до конца сентября, и его заменят кимоно для подготовки к зиме. Начиная с конца сентября, чтобы придать «теплый» вид, в течение этого сезона рекомендуют носить теплые цвета, такие как красный, коричневый и цвета осенних листьев.

Леспедеца одно из семи осенних растений в японской культуре с множеством маленьких красновато-пурпурных или белых цветков. Осенью обычно надевают кимоно с орнаментом из леспедеца.

Подобно леспедецу, японский ширококолокольчик также является одним из семи осенних растений в японской культуре, и его рекомендуется носить с этим узором с ранней осени до октября.

Зима

Зима — это время года, когда естественные цвета тускнеют. Для новогодних праздников популярны кимоно с красивыми узорами, такими как сосна, бамбук и слива. В то время как другие предпочитают кимоно с элегантными и причудливыми узорами зимних цветов на фоне снега.

Зеленый цвет сосны называют «вечнозеленым», поэтому кимоно с орнаментом из сосны можно носить и в течение всего года, но чаще все же ходят зимой.

Камелии имеют разные виды, которые цветут в разные месяцы года. Поскольку цветок известен как «дерево, знаменующее приход весны», наиболее подходящее время года для ношения кимоно с этим узором — с декабря по февраль. Если камелия сочетается с другими мотивами, ее можно носить все весь год.

Хризантема издавна использовалась как цветок с лечебными свойствами. По этой причине рисунок хризантем ассоциируется с желанием долголетия. Кимоно с таким рисунком можно носить круглый год, но рекомендуют носить осенью и зимой.

Узоры

В классических узорах кимоно используются уникальные японские мотивы. Тандзаку (маленькие кусочки цветной бумаги) используются для написания стихов хайку и танка, а использование его в качестве рисунка на кимоно является символом желаний академических успехов и успехов в работе. Кимоно с узорами танзаку обычно надевают с лета до осени. Узоры, такие как сосна, бамбук, слива, журавль, черепаха и феникс символизируют долголетие, их носят в таких случаях, как свадьбы. Узор складывающегося веера, расширяющегося наружу, считается символом растущего процветания и знаком удачи. Кимоно с таким рисунком обычно надевают в благоприятных случаях. Барабан Цудзуми используется в традиционной народной музыке и театре Но и Кабуки. Поскольку барабан издает красивый громкий звук, его узор на кимоно это мотив для пожелания хорошего урожая и успехов. Юсокумонё (有職文様) — это традиционные узоры, используемые в костюмах, мебели, каретах и архитектурных интерьерах благородных семей периода Хэйан и более поздних периодов. Однако этот термин появился только в современный период. Изначально пришел из Китая и развился в Японии. Благодаря такому дизайну кимоно с этими узорами можно носить круглый год. Типичные узоры включают Татеваку (立涌, мотив восходящего потока, рисунок вертикальные волнистые линии), Сейкайха (青海波, синие океанские волны, представляет собой геометрический рисунок, изображающий воду), Кикко (亀甲, дизайн панциря черепахи, олицетворяющий интеллект и долголетие), Кагомэ(籠目, шестиугольный дизайн, вдохновленный традиционным плетением корзин, защищает от зла), Итимацу (市松, клетчатый узор, ставший популярным в современности благодаря аниме Kimetsu no Yaiba).

Ретро узоры характеризуются множеством приглушенных цветов, передающих атмосферу ностальгии. Ключом к сочетанию цветов кимоно является сочетание строгих темных акцентных цветов и светлых тонов, таких как белый и бежевый. Это произведет впечатление зрелости и нежности и сделает все ретро-кимоно более сбалансированным. Также сочетание цветов с противоположными тонами одного цвета подчеркнет единство цветов и произведет спокойное впечатление.

С другой стороны, современные узоры (модерн) часто относятся к красочным кимоно, включающим узоры, которые редко использовались в классических кимоно, такие как множество точек или узоры розы.

А ретро-модерн узоры в каком-то смысле находятся между этими двумя стилями, где смело размещаются крупные классические узоры с использованием популярных современных узоров.

Тайсё-роман (Романтизм эпохи Тайсё) — стиль сочетающего в себе японский и европейский дизайн, который был популярен в период Тайсё и раннего периода Сёва. Этот период ознаменовался появлением западной культуры в различных формах, включая введение химических красителей. Это привело к созданию кимоно под влиянием ар-нуво и ар-деко. Кимоно с элементами геометрического ар-деко производились вместе с кимоно из шелка мейсен, которое носили как повседневную одежду. В кимоно под влиянием запада было много западных цветов, таких как розы, тюльпаны, в сочетании с геометрическими узорами, а также редкие и яркие цвета от химических красителей.

Аксессуары к кимоно

Есть ряд аксессуаров, которые можно носить с кимоно, и они различаются в зависимости от случая и использования. Некоторые из них носят церемониальный характер или носятся только по особым случаям, тогда как другие являются частью одежды кимоно и используются в более практическом смысле.

Хакама (袴) похожи на штаны, которые надевают поверх кимоно, чтобы прикрыть тело от талии до ступней. Может быть как разделенное (как юбка), так и не разделенное (как штаны). Хакама имеет долгую историю, восходящую к периоду Кофун (около 300–710 гг.). В периоде Хэйан (794–1185) хакама носили женщины высокого ранга при дворе. Но в период Эдо (1603-1868) женщинам было запрещено носить хакама из-за строгого дресс-кода, основанного на статусе. Единственным исключением были придворные дамы. В конце концов, рассвет женского образования пришелся на период Мэйдзи, когда было открыто несколько школ для девочек. В этих школах велись споры о дресс-коде, поскольку эти школы были в западном стиле со стульями. Традиционные кимоно не предназначены для сидения на стульях, так как они легко ослабляют кимоно. По этой причине правительство снова разрешило женщинам носить хакама. В наши дни их можно носить на различных официальных или неформальных мероприятиях. Их также носит мико в святилищах синто.

Гэта (下駄 ), деревянные сандалии. Придерживаются на ногах ремешками, проходящими между большим и вторым пальцами.

Таби (足袋), традиционные японские носки высотой до лодыжки с раздельным большим пальцем, для удобства ношения традиционной обуви.

Хатимаки (鉢巻), повязка на голову в традиционном японском стиле , предназначенная для защиты лица от пота. Символизирует у японцев непреклонность намерений и поддерживает боевой дух.

Хаори (羽織), жакет прямого покроя без пуговиц, надеваемый поверх кимоно или кимоно с хакама. Изначально носили мужчины, пока они не стали популярными как женская одежда. Также носили гейши в период Мэйдзи, но когда хаори стали обычным явлением, гейши отказались от этой практики. Обычная длина хаори — ниже пояса, но выше колена.

Харамаки (腹巻), пояс, закрывающий живот. Их носят из соображений здоровья, моды и суеверных соображений. Современные харамаки представляют собой широкую полосу эластичной ткани, которая надевается вокруг живота и скрепляется со стороны спины.

Оби (帯), тип японских поясов, носимых как мужчинами, так и женщинами поверх кимоно. Оби делятся на категории по их дизайну, формальности, материалу и использованию, и могут быть сделаны из нескольких типов ткани, с тяжелым парчовым переплетением для официальных случаев и легким шелковым оби для неформальных случаев. Оби также изготавливаются из других материалов, помимо шелка, таких как хлопок , конопля и полиэстер , хотя шелковые оби считаются необходимостью для официальных мероприятий. Самый формальный женский оби, мару-оби , технически устарел, его носят только некоторые невесты. Более легкая фукуро-оби заняла место мару-оби. Повседневная нагоя-оби является наиболее распространенным оби, используемым сегодня, а более причудливые из них могут даже быть приняты как часть полу-церемониального наряда. Использование причудливых декоративных узлов оби также сузилось, хотя в основном из-за уменьшения числа женщин, регулярно носящих кимоно, при этом большинство женщин завязывают свои оби в стиле тайко мусуби («Барабанный узел»). Цуке-оби , также известное как цукири-оби , приобрело популярность как предварительно завязанные ремни, доступные для людей с ограниченными физическими возможностями или не знающих, как носить оби.

Инро (印籠), традиционный японский футляр для мелких предметов, подвешенный к оби, который надевается на талию при ношении кимоно

Кинчаку (巾着), традиционная японская сумка или мешочек на шнурке, которую носят как кошелек или сумочку для ношения личных вещей.

Вагаса (和傘), традиционный японский зонтик из масляной бумаги. По традиции зонтики делали только из природных материалов, используя бамбук, бумагу васи, древесину.

В современное время нет дресс-кода, и молодые японки имеют мало поводов для надевания подобной одежды — обычно это самые важные семейные праздники, поэтому всё многие начинают отходить от традиций ношения кимоно, что понравилось, то и надели.

На чтение 22 мин Просмотров 1.4к.

Обновлено 20.06.2022

Кимоно – японская национальная одежда. В ней отразилось все: тонкая эстетика традиционной японской культуры, японское мироощущение и восприятие прекрасного, сила, мудрость и национальный характер народа. Кимоно, наряду с цветущей сакурой, самураями, чайными церемониями, стало визитной карточкой и символом Японии.

Конечно же, современные японцы не носят постоянно в повседневной жизни классическое кимоно. Но по-прежнему эта одежда – важная часть национальной культуры. Поэтому хотя бы один комплект сложного, красивого платья, которое представляется возможность надеть раз в несколько лет, есть практически в каждой японской семье. Без кимоно невозможно представить семейное торжество, праздники или фестивали.

О том, что такое кимоно, как менялась национальная японская одежда от эпохи к эпохе, каким этот наряд дошел до наших дней и как можно использовать его эстетику и символизм в современной одежде, поговорим в сегодняшней статье.

Содержание

- Что такое японское кимоно

- Что входит в комплект традиционного кимоно

- История кимоно

- Какие бывают японские кимоно

- Мужские кимоно

- Женское кимоно

- Детское кимоно

- Самые популярные виды кимоно

- Символы и значения, которые используются в оформлении кимоно

- Из какой ткани шьют современные кимоно, особенности кроя

- Как надевать и носить кимоно

- Особенности современного кимоно

- Современные образы с кимоно и влияние на мировую моду

- Как ухаживать за кимоно

Что такое японское кимоно

В японском языке слово «кимоно» дословно переводится как «одежда». Причем изначально этот термин применялся к любой одежде, независимо от ее вида и назначения. Но со временем так стали называть только определенный тип одежды, очень напоминающий запахивающийся халат с широкими рукавами без пуговиц и застежек, которую носили и до сих пор носят японские женщины, мужчины и дети.

Классическая форма японского кимоно, сформировавшаяся за прошедшие столетия, практически не изменилась до наших дней. И с определенного времени кимоно приобрело статус японского национального костюма.

Традиционное кимоно – это длинная одежда, закрывающая щиколотки, своеобразного кроя в форме буквы «Т». Для нее характерны прямые швы. Обязательная деталь – воротничок и рукава разной ширины, которые, как и другие детали наряда, могут многое сказать о хозяине кимоно, его социальном статусе, о том, для чего предназначено то или иное платье.

Например, кимоно с очень длинными, чуть ли не до пола, и очень широкими рукавами носят девушки на выданье. Символически такой наряд как бы сообщает окружающим, что молодая особа в поиске жениха.

Кимоно – это не только само платье. На самом деле это очень сложный комплект из множества составляющих его дополнительных предметов нижней и верхней одежды, специальной обуви и аксессуаров.

Что входит в комплект традиционного кимоно

Оби – мягкий широкий пояс, который надевают поверх кимоно. Он бывает мужским и женским. Традиционно его длина от 3,65 до 9,6 метра, ширина – 60 см. Это один из главных атрибутов, входящих в комплект. Его надевают поверх кимоно, оборачивают вокруг тела несколько раз и завязывают сложным бантом сзади.

Так делают все женщины, кроме дзёро – «жриц любви», которые завязывают бант всегда только спереди. Это куртизанки, представительницы одной из самых древнейших профессий, но не гейши.

Способ завязывания пояса у незамужних девушек также несколько иной, чем у замужних. Первые завязывают бант так, чтобы концы пояса выступали. А вторые укладывают концы плоско.

Под верхнее основное платье обычно надевают особое белье и еще одно или несколько нижних платьев – разновидностей кимоно:

- Нагадзюбан (дзюбан) – скроенная по типу кимоно нижняя рубаха, которая есть в мужском и женском наряде. Носят ее для того, чтобы шелковое верхнее кимоно, за которым сложно ухаживать, защитить от соприкосновения с телом, от загрязнений и пота.

- Сасоеке и хададзюбан – это нижнее белье в виде широких шаровар и тонкой рубашки, которые могут быть также между собой соединены. Их носят женщины под нагадзюбаном.

- Косоде – кимоно с короткими рукавами из комплекта нижнего белья.

- Хакама – широкие плиссированные брюки в виде юбки с очень широкими, сшитыми или разделенными штанинами. Этот вид одежды традиционно носили мужчины: всадники, самураи, бойцы некоторых видов боевых искусств, синтоистские жрецы, в неформальной обстановке. С недавних пор женщины также стали носить хакаму. Например, при участии в выпускных церемониях.

- Хиёки – разновидность нижнего кимоно. Этот предмет комплекта сегодня используется только в одежде для официальных мероприятий, например, свадеб.

К верхней одежде, дополняющей кимоно, относятся:

- Хаори – жакет, который надевают поверх кимоно и закрепляют как поясом особым шнуром хаори-химо. Кимоно, дополненное хаори, выглядит более официальным. Его носят как мужчины, так и женщины. Хотя раньше хаори входил только в мужские комплекты. В мужском современном хаори расписывается подкладка. Женские модели шьют из узорчатого полотна, и они длиннее мужских. Самурайские хаори отличаются особым покроем и небольшим разрезом в нижней части спины.

- Катагина – это накидка из плотной ткани без рукавов, но с накрахмаленными плечами. Ее надевали поверх официального костюма самураи, что придавало им более внушительный вид.

Аксессуары:

- Оби-ита (Маэ-ита) – это обитая тканью тонкая доска, которую носят женщины под оби для сохранения его формы.

- Датэдзимэ – используемый с той же целью, что и оби-ита, тонкий пояс.

- Косихимо – специальные веревочки, шнурки, завязки, тонкие пояски, с помощью которых кимоно фиксируется во время надевания.

- Канзаси (канзаши) – это всевозможные украшения, заколки, булавки, шпильки, гребни, которые носят в прическе, предусмотренной к кимоно. Мотивы и узоры, которые используются мастерами при изготовлении таких украшений, зачастую объединены общей тематикой рисунков на кимоно.

Ни одна японка никогда не наденет традиционный костюм с современной обувью. Традиционный наряд дополняет специальная обувь:

- Дзори – кожаные или тканевые сандалии, напоминающие по виду обыкновенные сланцы-шлепанцы. Носят их мужчины и женщины. Они могут быть декорированными или очень простыми.

- Гэта – деревянные сандалии, которые чаще всего носят с кимоно юкато.

- Варадзи – сандалии, сплетенные из соломы, в которых ходят в основном монахи.

- Окобо – высокие туфли, которые носят в основном гейши или девушки майко. Передвигаться в них очень сложно – можно только очень мелкими шажками. И легко упасть.

- Таби – модель низких носков с большим пальцем, отделенным от остальных. Их носят часто с дзори.

История кимоно

Находки археологов свидетельствуют, что самые первые японские платья кимоно появились примерно в V веке н. э. Они очень были похожи на китайскую традиционную одежду – ханьфу. Предположительно, именно особенности одежды китайской династии Тан легли в основу японского кимоно.

В период Хэйан (794-1192) – время расцвета моды и формирования японской эстетической культуры – кимоно приобрело свой современный и окончательный вид, который остается с тех пор неизменным.

При пошиве одежды стали применять новую технологию – «метод прямого кроя», который не стесняет движений. А это очень важно в культуре японцев, которые много сидят на полу.

Кимоно стали шить и шьют по сей день стандартного одинакового размера из цельного полотна без подгонки по фигуре. Затем девушки с помощью веревочек, прищепок, различных подвязок, подворачивая и сворачивая кимоно, доводят кимоно до своего размера, роста и делают, как им удобно. Причем делают это виртуозно.

Таким способом наряд можно приспособить под любую фигуру и носить в любую погоду. Сшитое из льняной тонкой материи – летом, а кимоно из нескольких толстых слоев подходит и для зимы.

Специально для кимоно выпускали ткань нужной ширины и длины, удобную для кроя и пошива. Единственный кусок ткани оставалось только разрезать на несколько прямоугольников и соединить между собой. Одежду шили и расшивали только вручную.

Чтобы кимоно меньше мялось, а слои одежды не путались между собой, их сшивали свободными, крупными стежками. Так делали еще и по той причине, что перед стиркой кимоно распарывали. И после снова сшивали.

Сейчас, конечно же, современные ткани и способы ее очистки от загрязнений свели на нет необходимость в этом. Хотя в некоторых местах такой способ стирки сохранился. Также не всегда соблюдается требование шить только вручную, без использования швейной машины.

Понятно, что такая одежда из тонкой натуральной ткани, сшитая и расшитая вручную, стоила очень много и не все жители страны, особенно из низшего сословия, могли позволить себе шелковое кимоно. Большинство японцев брали кимоно напрокат или носили переработанную одежду. Относились к ней японцы всегда очень бережно.

Материал, из которого было сшито старое кимоно, никогда не выбрасывается. Правило – никогда не выбрасывать и повторно использовать материал, из которого было сшито старое кимоно, пришло в современность из глубины веков, и японцы всегда ему следуют.

Его используют повторно для пошива самых разных вещей: коротких халатов хаори, одежды для детей, сумок, заколок с цветами – канзаши, для ремонта вещей, сходных по расцветке, для изготовления темари (традиционная японская техника вышивки на шарах) в качестве основы для сплетенных из полосок разорванных старых кимоно.

Некоторые даже умудрялись распускать по ниточке старый материал, из которых снова сплетали новое полотно, которое могло использоваться для мужского оби.

Примерно в XVI веке кимоно стало основной одеждой для японцев разного сословия, социального положения, мужчин, детей и женщин. А в последующие столетия случилось бурное развитие и расцвет японского текстильного искусства.

Однако, XIX век принес в японское общество, культуру и одежду драматические изменения. Западная одежда начала повсеместно внедряться. В ней японцы должны были появляться в общественных местах, на службе. И к середине XX столетия европейская одежда стала повседневной нормой.

Японское кимоно поменяло статус повседневной одежды на культовый наряд для особых важных событий, происходящих в жизни семьи и общества. Например, кимоно с узким рукавом, стало самой официальной одеждой для замужней женщины. При этом рукава и спина украшаются фамильным гербом. Кимоно с одним широким рукавом символизирует, что женщина одинокая.

Исторические комплекты с полным набором аксессуаров и дополнений (а их количество, особенно в женском традиционном кимоно, может насчитывать до 12 деталей) сейчас практически не используются в повседневной жизни. Такие полные комплекты остались в нарядах невест, гейш. И то нечасто.

Подобрать идеально все части в таком многослойном наряде, чтобы все это смотрелось гармонично, сложно. И уж тем более, надеть все это на себя самому. В обычных ситуациях носят обычно упрощенные комплекты, которые состоят из одного-двух слоев, иногда с имитацией ложного воротничка.

Какие бывают японские кимоно

Одежда, известная многим из нас под общим названием «кимоно», на самом деле имеет множество других названий, различия между которыми отлично знают японцы. Об обладателе или обладательнице кимоно очень многое могут рассказать разнообразные формы и детали одежды, покрой, узоры, расцветки.

Традиционно японские наряды делятся на женские и мужские. Японский женский и мужской халат отличаются друг от друга кроем, цветом, деталями, используемыми национальными символами.

Мужские кимоно

Мужчины чаще всего носят комплекты из темного матового материала приглушенных оттенков черного, синего, зеленого, коричневого, с семейными гербами на груди, спине, рукавах. Ткань с узором допускается, но только для неофициальных случаев.

Иногда мужской костюм дополняют традиционным жакетом хаори, который надевают поверх кимоно, или широкими штанами или юбкой – хакама.

Мужской комплект кроится всегда по одной форме, состоит из пяти элементов и сопровождается гэта и таби. Рукава неглубокие и чаще всего пришиты полностью к основной части наряда. В отличие от женских комплектов, мужские с небольшим количеством сопутствующих предметов не требуют посторонней помощи при облачении в кимоно.

Современное мужское кимоно, так же, как и женское, приобрести сегодня можно того размера, который нужен. Проблема возникает только при пошиве или покупке кимоно большого размера, так как по традиции его шьют из одного локального рулона материи.

Женское кимоно

Женские комплекты намного сложнее и многослойнее мужских. Их подбирают в зависимости от социального статуса и возраста хозяйки, сезона и событий, для которых наряд предназначен. От этого, а также от стиля, модели, ткани и цвета, зависит смысловая нагрузка женского кимоно, которую оно несет окружающим.

В женском кимоно важную роль играет цвет. Незамужние молодые девушки могут себе позволить более легкомысленные наряды, полностью расшитые цветами пастельных оттенков – розовых, голубых, персиковых. Для женщин постарше характерен наряд черного цвета с узорами ниже талии и на рукавах.

Повседневные кимоно отличаются неброским мелким рисунком зеленоватых, коричневых, бежевых оттенков. Самые яркие модели кимоно с красной подкладкой позволительно носить гейшам.

Детское кимоно

Японские дети тоже носят традиционный наряд. Для маленьких детей кимоно обычно перешивают из взрослого женского или мужского комплекта. По крою разноцветный детский халатик, чаще всего из стеганой ткани, – это несложная конструкция. Для особых случаев детям постарше шьют наряды по аналогии со взрослыми моделями. Но обычно более ярких расцветок.

Самые популярные виды кимоно

- Фурисоде – комплект с широкими, длинными рукавами, которые в период Эдо были способом выразить чувства и сообщить о готовности девушки выйти замуж. Такой наряд надевают незамужние женщины и девушки на свадьбы, на церемонию совершеннолетия или на чайную церемонию. Шьют такое кимоно из шелка хорошего качества ярких расцветок.

- Томесоде – комплект для замужней женщины, предназначенный для официальных событий. Например, свадьба дочери. Кимоно отличается более узкими и короткими рукавами, элегантными, простыми узорами на уровне колен. Чаще всего такие комплекты шьют в традиционном черном цвете с вышивкой пяти фамильных гербов на спине, рукавах, груди. Иро-томесоде – цветное томесоде, которое менее торжественно и строго.

- Хомонги – женский наряд (независимо от социального статуса), предназначенный для официальных мероприятий. Шьют его из однотонной ткани с одинаковым принтом в нижней части подола, на плечах, на рукавах.

- Иромудзи – простой тип менее красочного и узорчатого кимоно из однотонной ткани любого цвета (кроме белого и черного) без каких-либо рисунков. Исключение – цветной принт на талии. Предназначено для любых женщин. Например, для родственников тех, кто вступает в брак. В зрелом возрасте предпочтительнее элегантные оттенки.

- Цукекаге – более сдержанный и скромный аналог кимоно хомонги с принтом в нижней части платья. Его могут надевать все женщины на свадьбы друзей, чайные церемонии.

- Учикаке (утикаке) – наряд, украшенный парчой, который предназначен для артистов и невест. Это кимоно длиннее других разновидностей, часто достает до самого пола. Его не завязывают поясом оби. В нарядах для невесты используется белый и красный цвет, для артистических кимоно допускается любая расцветка.

- Комон – повседневное кимоно, которое могут носить в городе все: мужчины и женщины независимо от социального статуса. Для него характерен мелкий, повторяющийся по всей одежде принт. Шьют кимоно из шерсти, натурального и искусственного шелка, полиэстера. Это было самое распространенное платье-кимоно в Японии до момента, когда оно было вытеснено западной одеждой.

- Сусохики/Хикидзури – кимоно танцовщиц, которые исполняют японские традиционные танцы, и гейш. Это очень длинное платье, юбка которого волочится по полу. Воротник в этой модели расположен ниже, чем в обычном кимоно.

- Широмуку – наряд предназначен для невесты на традиционной свадьбе. Это очень длинное белое платье. В таком же цвете выполнены все дополнительные аксессуары.

- Мофуку – кимоно черного цвета. Это траурная одежда, которую надевают женщины и мужчины во время похорон.

- Дзюнихитоэ – сложный и элегантный тип дорогого кимоно, который носили придворные японские дамы. Комплект состоит из нескольких слоев шелковой одежды. Самый нижний слой кимоно сделан из белого шелка. Эта разновидность традиционной одежды сегодня встречается достаточно редко. Но подобные модели все-таки можно увидеть на фестивалях, в фильмах, в музеях, на некоторых грандиозных мероприятиях в Императорском доме.

- Юката – это вид кимоно, хорошо известный иностранцам. Представляет из себя легкий неофициальный наряд для женщин и мужчин из натуральных тканей привлекательных расцветок: хлопка, конопли, льна. Предназначен для летних фестивалей, посещений горячих источников, встречается в одежде служащих традиционных японских отелей. В прежние времена традиционная юката выпускалась только в парной комбинации сине-белых и бело-черных цветов и использовалась как халат после водных процедур.

- Онсэн-кимоно – это неформальный вид кимоно в виде легких халатов, которые можно увидеть в Японии на горячих источниках, в банях, местах отдыха. Шьют их из легкого в уходе мягкого хлопка. Использовать качественный халат кимоно онсэн можно не только в общественных местах, но и для отдыха дома и личного пользования.

Символы и значения, которые используются в оформлении кимоно

В простом по форме японском кимоно большое значение уделяется внешнему оформлению: выбору цвета, рисунка и его расположению, фактуры материала, некоторых деталей одежды, стиля, дополнительных аксессуаров. Все это в комплексе указывает на социальный статус, вкус, возраст, пол, культурные особенности личности. На самом деле в этом вроде бы утилитарном предмете скрыт глубокий философский смысл.

При окрашивании нитей для холста, из которого шили кимоно, а это чаще всего делали вручную с помощью сока растений или отваров коры, мастер учитывал множество нюансов. Например, узор наносился с учетом посадки изделия на человеке, который бы двигался вместе с частями тела.

Мотивы для украшения наряда, многие из которых происходят из Китая, должны отражать эмоции и личный мир хозяина, время года, приурочены к особенностям событий, по случаю которых будет надето кимоно.

Традиционную одежду носили для привлечения удачи, получения благословления богов. Например, изображение цветущей вишни на комплекте символизировало отличный урожай, хорошее настроение. Такое кимоно можно было носить круглый год. Изображение журавлей, фигурирующих во многих мифах, обитающих в земле бессмертия птиц, по преданию, приносит счастливую, долгую жизнь и удачу.

Хризантемы – цветок японского императора. Символизирует удачный урожай, долгую жизнь, непринужденность, хорошее настроение, безразличие к внешнему блеску. Утка-мандаринка – ее изображение на тканях кимоно означает символ абсолютной верности и вечной любви. Его часто наносят при оформлении нарядов для свадьбы.

Красный цвет – цвет сафлоры. Комплекты такого цвета чаще всего выбирают молодые девушки. Фиолетовый цвет – в японской эстетике это цвет бесконечной любви. Аисты – символ красоты и долгой жизни. Птица Феникс – символ женственности и одновременно вызывающий ассоциации с мужественностью драконов. Такие узоры часто используются в свадебных комплектах.

В японском текстильном искусстве при оформлении ткани с древности и по сей день используются традиционные графические символы: это всевозможные цветовые пятна, орнамент из полос и лент, которые символизировали удачу и очищение, им приписывались магические свойства, способность отгонять злых духов. Образуя на поверхности кимоно ритмично колышущиеся, плавные линии, разделяя плоскость на повторяющиеся узоры, они образуют сложные структуры и оптические иллюзии.

Философский смысл заложен даже в умении складывать кимоно строго определенным способом. Если ритуал не был нарушен, в итоге получится прямоугольник. И это как бы косвенно указывает на то, что человек, который надевает одежду должным образом и затем правильно ее складывает, стремится и в жизни правильно думать и совершать правильные действия. К тому же это еще и признак воспитанной в себе аккуратности.

Из какой ткани шьют современные кимоно, особенности кроя

Материалы, которые традиционно используются при пошиве японского кимоно, – шелк, сатин, хлопок. Гораздо реже полиэстер. Лучший выбор – конечно же, натуральный, качественный шёлк, например, одна из его разновидностей – мягкий, с изысканным блеском, но плотный и тяжелый шелк дюпон.

Нити для него, как и столетия назад, прядут сразу из двух коконов шелкопряда по старинной технологии. При этом должна получиться идеально ровная шелковая нить, которую определенным образом обрабатывают: сушат, окрашивают растительными красителями, разглаживают. Затем из нее на ткацких педальных машинах вручную из нитей основы и утка составляют различные узоры.

Конструктивный крой кимоно основан на традиционном представлении японцев о красоте человеческой фигуры. По японской эстетике – красивое тело то, в котором меньше неровностей и выпуклостей. Поэтому, в отличие от европейской одежды, которая, как правило, садится по фигуре, кимоно скрывает недостатки фигуры, подчеркивая лишь талию и плечи, делая акцент на плоскости и равномерности, а не на рельефе.

Одна из главных особенностей традиционной одежды – прямые линии кроя в форме буквы «Т». Любое кимоно: женское, мужское, детское – никогда не подгоняется по длине и ширине под конкретную фигуру.

Наряд подгоняется по фигуре уже при облачении, особым способом убирая в складки излишки материи и закрепляя их при помощи пояса оби и специальных веревочек.

Кимоно – это настоящее произведение прикладного искусства. Чтобы добиться хорошего результата, надо подобрать нужную ткань и правильно ее раскроить. Для одного женского кимоно потребуется цельный кусок ткани шириной 36-72 см и длиной 9-12 метров.

Кимоно – это сложная конструкция, которая состоит из множества деталей. Особенно много их насчитывается в женских моделях – до 15 штук. Есть общие элементы, которые присутствуют и в мужских, и в женских кимоно. При этом все детали выкраиваются в форме прямоугольника. Не допускается каких-либо закруглений и овалов.

Из четырех выкроенных полос две идут, чтобы покрыть спереди и сзади тело. Еще две полосы используются как рукава, которые выглядят как мешкообразный прямоугольник разной длины и ширины в зависимости от того, для кого предназначена та или иная модель.

В мужских моделях рукав пришивается к основной конструкции. В женских же втачивается в подмышечное отверстие. Для оформления кимоно спереди с левой и правой стороны выкраиваются еще две нешироких полосы. Также прямоугольные полоски небольшого размера используются для основного воротника и накладного.

Как надевать и носить кимоно

Процесс облачения в кимоно схож с работой художника. От того, насколько удачно удастся соединить традиционный костюм не только с внешностью, но главное – с характером человека, зависит, станет ли кимоно настоящим украшением или нет.

В основе философии традиционного японского костюма заложены три основных понятия – красота, любовь, этикет. Кимоно, закутавшее плотно с головы до ног тело, широкие рукава, длинная юбка без разреза, широкий пояс, фиксирующий, словно корсет, делают движения человека мягкими и неторопливыми. Это вызывает ощущение некоторой уверенности в себе, спокойствия. С другой стороны, по японской эстетике, такая одежда определенным образом воспитывает такие качества, как покорность и смирение.

В женщинах национальный костюм подчеркивает их хрупкость и женственность. В мужчинах – достоинство и мужественность.

Самостоятельно надеть кимоно, особенно многослойное, с несколькими нижними, под богато украшенное верхнее, завязать пояс оби, очень сложно. Для европейцев практически невозможно. Но японцы с этим справляются. Их с детства учат искусству надевать и носить традиционный наряд.

Женское и мужское кимоно всегда запахивают на правую сторону. То есть левый конец должен быть всегда поверх правого. Исключение – погребальное кимоно: на умершем одежду всегда запахивают на левую сторону.

Особое искусство – завязать широкий женский пояс оби в красивый, пышный бант, который находится на спине. Причем, чтобы придать фигуре ровную поверхность, без каких-либо изгибов, ткань тщательно наматывается на талию, чтобы тем самым ее скрыть. Мужской пояс не такой широкий, как женский. Его завязывают почти на линии бедер. Задний шов кимоно должен проходить строго по центру. Белый нижний воротничок должен находиться строго под основным воротником кимоно.

По японскому этикету, человек, который одет в национальный костюм, не может обнажать и показывать какие-либо части тела и ноги, скрытые одеждой.

Особенности современного кимоно

Качественные кимоно сегодня очень дорогие. Их стоимость зависит от сложности модели, от набивки узора, вышивки на ткани. Особенно ценятся среди коллекционеров традиционные вышитые кимоно ручной работы из старинного роскошного текстиля – шелка дюпон, который до сих пор производится в японской глухой деревне из нитей шелкопряда.

Особая тема – винтажное кимоно. Такие комплекты по цене гораздо дешевле новых можно приобрести в ателье-магазинах кимоно, куда их сдают по прошествии лет японки, избавляясь от запасов национальной одежды на все случаи жизни.

Японки носят такие дорогие наряды, доставшиеся им в наследство от бабушек и прабабушек, по особым случаям.

В большом количестве производятся кимоно для тренировок при занятиях восточными единоборствами. По сути, ежедневно кимоно носят профессиональные борцы сумо, то есть они обязаны надевать традиционную одежду всякий раз, когда находятся на публике вне ринга.

Для массового потребителя производятся более дешевые изделия из синтетического материала яркой окраски. Основной производитель – Китай.

Современные образы с кимоно и влияние на мировую моду

С начала XX века японское кимоно, как и в целом культура жителей острова, предметы быта, стали активно влиять на европейскую моду и вкусы не только дизайнеров, но и простых людей.

В прошлом столетии стали появляться кимоно с новыми рисунками, которые расширяли представление о дизайне традиционного наряда. Японцы, понимая, что европейские женщины вряд ли будут облачаться в сложные конструкции и завязывать широкие пояса, стали шить модели с поясом из той же ткани и добавлять дополнительные вставки, делая пригодным кимоно для использования в качестве нижней юбки.

Кимоно – вещь универсальная, простая и внесезонная. В зависимости от выбора модели и ткани, подходит одинаково хорошо для прохладного времени и жарких дней.

Оно может выступать в самых разных ролях, создавая тот или иной образ и задавая комплектам разного назначения и стиля особое настроение. Например, это может быть изысканный вечерний наряд, пляжная или домашняя одежда. Кимоно может взять на себя роль топа или блузки, легкой накидки, жакета, пальто или невесомого блузона. А для лета это просто незаменимая вещь – не стесняющая движений и комфортная в жару.

Европейские модницы, которым пришелся по вкусу новый тренд, с удовольствием стали создавать новые образы на основе кроя кимоно: многослойные комплекты со стилизованным платьем различной длины, просторные накидки, блузки. Все это отлично сочетается с современной одеждой: джинсами и короткими шортами, юбками, платьями, футболками и стильной обувью – слипонами, кедами, босоножками, кроссовками.

С приходом в мир моды стиля «бохо» кимоно быстро обосновалось в гардеробах модных последовательниц этого направления.

Как ухаживать за кимоно

Японское традиционное кимоно нельзя стирать в стиральной машине. Только вручную или сдавать в химчистку. Хранить расправленным на специальной стойке. Если таковой нет, можно комплект переложить бумагой и сложить, не перегибая.

Photograph of a man and woman wearing traditional clothing, taken in Osaka, Japan.

There are typically two types of clothing worn in Japan: traditional clothing known as Japanese clothing (和服, wafuku

), including the national dress of Japan, the kimono, and Western clothing (洋服, youfuku), which encompasses all else not recognised as either national dress or the dress of another country.

Traditional Japanese fashion represents a long-standing history of traditional culture, encompassing colour palettes developed in the Heian period, silhouettes adopted from Tang dynasty clothing and cultural traditions, motifs taken from Japanese culture, nature and traditional literature, the use of types of silk for some clothing, and styles of wearing primarily fully-developed by the end of the Edo period. The most well-known form of traditional Japanese fashion is the kimono, with the term kimono translating literally as «something to wear» or «thing worn on the shoulders».[1] Other types of traditional fashion include the clothing of the Ainu people (known as the attus)[2] and the clothes of the Ryukyuan people which is known as ryusou (琉装),[3][4] most notably including the traditional fabrics of bingata and bashōfu[2] produced on the Ryukyu Islands.

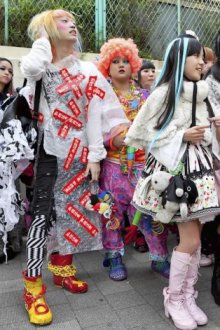

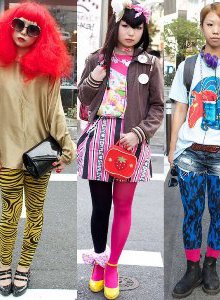

Modern Japanese fashion mostly encompasses yōfuku (Western clothes), though many well-known Japanese fashion designers – such as Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo – have taken inspiration from and at times designed clothes taking influence from traditional fashion. Their works represent a combined impact on the global fashion industry, with many pieces displayed at fashion shows all over the world,[5] as well as having had an impact within the Japanese fashion industry itself, with many designers either drawing from or contributing to Japanese street fashion.

Despite previous generations wearing traditional clothing near-entirely, following the end of World War II, Western clothing and fashion became increasingly popular due to their increasingly-available nature and, over time, their cheaper price.[6][verification needed] It is now increasingly rare for someone to wear traditional clothing as everyday clothes, and over time, traditional clothes within Japan have garnered an association with being difficult to wear and expensive. As such, traditional garments are now mainly worn for ceremonies and special events, with the most common time for someone to wear traditional clothes being to summer festivals, when the yukata is most appropriate; outside of this, the main groups of people most likely to wear traditional clothes are geisha, maiko and sumo wrestlers, all of whom are required to wear traditional clothing in their profession.

Traditional Japanese clothing has garnered fascination in the Western world as a representation of a different culture; first gaining popularity in the 1860s, Japonisme saw traditional clothing – some produced exclusively for export and differing in construction from the clothes worn by Japanese people everyday – exported to the West, where it soon became a popular item of clothing for artists and fashion designers. Fascination for the clothing of Japanese people continued into WW2, where some stereotypes of Japanese culture such as «geisha girls» became widespread. Over time, depictions and interest in traditional and modern Japanese clothing has generated discussions surrounding cultural appropriation and the ways in which clothing can be used to stereotype a culture; in 2016, the «Kimono Wednesday» event held at the Boston Museum of Arts became a key example of this.[7]

History[edit]

Yayoi period (Neolithic to Iron Age)[edit]

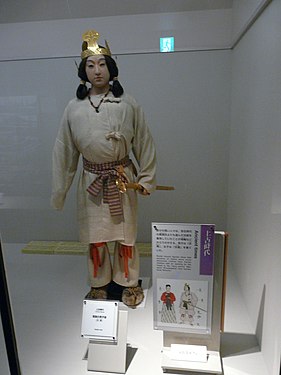

Reconstructed Yayoi clothing

Little is known of the clothing of the Yayoi period. In the 3rd-century Weizhi Worenchuan (魏志倭人伝 (Gishi Wajinden), a section of the Records of the Three Kingdoms compiled by Chinese scholar Chen Shou),[8][better source needed] there is some description of clothing worn in Japan. It describes broad cloth (possibly double-width), made into unshaped garments by being tied about the waist and shoulders.[9]

Kofun period (300–538 CE)[edit]

-

Museum-reconstruction figurines (conducting religious ceremony; note shide)

-

-

Reconstruction

-

Haniwa figure with reconstruction

-

Figure (reconstruction?) from Honshu, decorated with red pigment.

-

-

Haniwa figure with reconstruction

-

-

6th-century figure

-

-

Figure in a loincloth

Until the 5th century CE, there is little artistic evidence of the clothing worn in Japan.[10] Kofun period clothing is known from clay sculptures used atop haniwa offering cylinders.[11] These were used in the 5th and 6th century,[10] though most haniwa have no sculpture on top.[11] These figures likely do not represent everyday dress; they may represent riding dress. Many wear armour.[10]

In the Kofun period, the right side was wrapped over the left (unlike in China), and the overlapped edge was secured with ties on the right side. Sleeves and trousers were tubular. Female figures often wear a skirt, with male figures wearing trousers tied with garters just above the calf, so that they balloon over the knee, allowing freedom of movement.[10] Mo, wrapped skirts, were worn by men and women, sometimes over hakama (trousers).[9]

Traditional Chinese clothing had been introduced to Japan via Chinese envoys in the Kofun period, with immigration between the two countries and envoys to the Tang dynasty court leading to Chinese styles of dress, appearance and culture becoming extremely popular in Japanese court society.[12] The Imperial Japanese court quickly adopted Chinese styles of dress and clothing.[13] As early as the 4th century CE, images of priestess-queens and tribal chiefs in Japan depicted figures wearing clothing similar that of Han dynasty China.[14] There is evidence of the oldest samples of shibori tie-dyed fabric stored at the Shōsōin Temple being Chinese in origin, due to the limitations of Japan’s ability to produce the fabrics at the time[15] (see tanmono).

Asuka period (538–710 CE)[edit]

-

Replica of the dress of the leftmost figure in the preceding picture; mo with stripes and frill

-

Replica of the dress of the center-right figure in the preceding picture

-

Contemporary men’s dress, with green hō, white hakama, and kanmuri cap. This reconstruction is probably outdated; the hō should be shorter, with a short pleated frill beneath, as in the women’s costume.[9]

The Asuka period began with the introduction of Buddhism, and the writing system of Chinese characters to Japan; during this time, Chinese influence over Japan was fairly strong.[10]

Judging by the depictions in the Tenjukoku Shūchō Mandala, during the reign of Empress Suiko (593–628), male and female court dress were very similar. Both wore round-necked front-fastening hō with non-overlapping lapels, the front, collar, and cuffs edged with contrasting fabric, possibly an underlayer; the ran skirt, above knee-length, had a matching edge. Below the ran and extending below it to about knee length, a more heavily-pleated contrasting skirt called a hirami was worn. Below the hirami, men wore narrow hakama with a contrasting lower edge, and women wore a pleated mo long enough to trail.[9]

The Takamatsuzuka Tomb (c. 686 CE)[17] is a major source of information for upper-class clothing of this period. By this time, the hō lapels overlapped (still right side over left), and the hō and mo were edged with pleated frills, replacing the hirami. Kanmuri (black gauze caps stiffened with lacquer) were being worn by male courtiers, and were regulaed in the 11th regnal year of Emperor Tenmu (~684 CE); this fashion persists in formal use into the 21st century.[9]

Nara period (710–794)[edit]

-

Women’s dress, with overvest, overskirt, waist sash, and stole

-

Men’s dress, with kanmuri hat, hakama, ornate sash, shaku and sword.

-

Children’s dress, late 8th century, 2005 reconstruction

-

In contemporary art

-

Nara court dress with stole, apron and overvest, 2009 reconstruction

-

Tarikubi collar, and lower garments outermost

-

Agekubi outer collar, with upper garments outermost

Nara-period upper-class clothing was much simpler than some later styles, taking no more than a few minutes to don, with the clothing itself allowing for freedom of movement. Women’s upper-class dress consisted of a left-over-right lap-fronted top (over a similar underrobe),[10] and a wrapped, pleated skirt (mo).[18][19] Women also sometimes wore a lap-fronted overvest, and a narrow rectangular stole. Men’s upper-class dress had narrow, unpleated (single-panel) hakama (trousers) under a loose, mandarin-collared coat (hō (袍)),[citation needed] with elaborate hats of stiffened open-weave black cloth (kanmuri). Clothing was belted with narrow sashes.[18]

Nara-period women’s clothing was heavily influenced by Tang-dynasty China. Women adopted tarikubi (垂領, «drape-necked») collars, which overlapped like modern kimono collars, though men continued wearing round agekubi (上領, «high-necked») mandarin collars, which were associated with scholasticism, only later adopting tarikubi. Lower-body garments (mo and hakama) had been worn under the outermost upper-body garments, but now, following the newer Chinese fashion, they transitioned to being worn on top (again, by women, but not yet by men).

In 718 CE, the Yoro clothing code was instituted, which stipulated that all robes had to be overlapped at the front with a left-to-right closure, following typical Chinese fashions.[20]: 133–136 China considered right-over-left wraps barbaric.[10] This convention of wear is still followed today, with a right-to-left closure worn only by the deceased.[20]

In 752 CE, a massive bronze Buddha statue at Tōdai-ji, Nara, was consecrated with great ceremony. The ceremonial clothing of attendees (probably not all made in Japan) was preserved in the Shōsō-in.[10][21] Most of them close left-over-right, but some abut or overlap right-over-left. Collar shapes include narrow, round or v-shaped. There is craftsmen’s clothing in asa (domestic bast fiber), with long, round-collared outer robes. Richer garments in silk are ornamented with figural and geometric patterns, woven and dyed; some have flaring sleeves. Aprons, hakama, leggings, socks and shoes have also been preserved.[10]

Social segregation of clothing was primarily noticeable in the Nara period (710-794), through the division of upper and lower class. People of higher social status wore clothing that covered the majority of their body, or as Svitlana Rybalko states, «the higher the status, the less was open to other people’s eyes». For example, the full-length robes would cover most from the collarbone to the feet, the sleeves were to be long enough to hide their fingertips, and women carried fans were carried to protect them from speculative looks.[22]

Heian period (794–1185)[edit]

During the Heian period (794-1193 CE), Japan stopped sending envoys to the Chinese dynastic courts. This prevented Chinese-imported goods—including clothing—from entering the Imperial Palace and disseminating to the upper classes, who were the main arbiters of traditional Japanese culture at the time and the only people allowed to wear such clothing. The ensuing cultural vacuum facilitated the development of a Japanese culture independent from Chinese fashions. Elements previously lifted from the Tang Dynastic courts developed independently into what is known literally as «national culture» or «kokufū culture» (国風文化, kokufū-bunka), the term used to refer to Heian-period Japanese culture, particularly that of the upper classes.[23]

Clothing became increasingly stylised, with some elements—such as the round-necked and tube-sleeved chun ju jacket, worn by both genders in the early 7th century—being abandoned by both male and female courtiers. Others, such as the wrapped-front robes, also worn by men and women, were kept. Some elements, such as the mo skirt worn by women, continued on in a reduced capacity, worn only to formal occasions;[12] the mō (裳) grew too narrow to wrap all the way around and became a trapezoidal pleated train.[24] Formal hakama (trousers) became longer than the legs and also trailed behind the wearer.[19] Men’s formal dress included agekubi collars and very wide sleeves.[10]

The concept of the hidden body remained, with ideologies suggesting that the clothes served as «protection from the evil spirits and outward manifestation of a social rank». This proposed the widely held belief that those of lower ranking, who were perceived to be of less clothing due to their casual performance of manual labor, were not protected in the way that the upper class were in that time period. This was also the period in which Japanese traditional clothing became introduced to the Western world.[6][dubious – discuss]

During the later Heian period, various clothing edicts reduced the number of layers a woman could wear, leading to the kosode (lit., «small sleeve») garment—previously considered underwear—becoming outerwear by the time of the Muromachi period (1336-1573 CE).

-

The courtiers in the foreground are wearing their hitoe off-the-shoulder, showing the kosode beneath.

-

Tarikubi collars on husband and wife, in their home. Note red hakama of standing woman.

-

(Sashinuki)/nu-bakama and agekubi collar in men’s court dress

Kamakura period (1185–1333)[edit]

-

Fugen and the Ten Rasetsunyo, detail. Note red and purple naga-bakama with trailing waist ties.

-

Empress Shoshi and son, 13th century illustration. Pale pleated mō train

-

Simple unisex everyday dress, kosode and hakama, matching

-

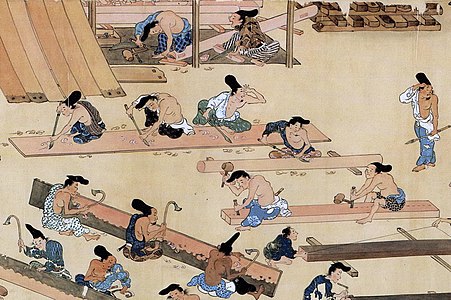

Carpenters in common dress, 1309; kosode and hakama do not match

Muromachi period (1336–1573 CE)[edit]

Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568–1600)[edit]

-

The kosode worn as outerwear. Note wider cut, and unisex narrow obi and shorter sleeves. Matsuura byōbu, c. 1650

Originally worn with hakama, the kosode began to be held closed with a small belt known as an obi instead.[12] The kosode resembled a modern kimono, though at this time the sleeves were sewn shut at the back and were smaller in width (shoulder seam to cuff) than the body of the garment. During the Sengoku period (1467-1615)/Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568-1600), decoration of the kosode developed further, with bolder designs and flashy primary colours becoming popular.[citation needed] By this time, separate lower-body garments such as the mō and hakama were almost never worn,[19] allowing full-length patterns to be seen.

Edo period (1603–1867)[edit]

The overall silhouette of the kimono transformed during the Edo period due to the braodening of the obi, lengthening of the sleeves, and the style of wearing multiple layered kimono. (Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Plum Blossoms at Night, woodblock print, 19th century)

During the Edo period (1603–1867 CE), both Japan’s culture and economy developed significantly. A particular factor in the development of the Edo period was the early Genroku period (1688–1704 CE), wherein «Genroku culture» — luxurious displays of wealth and increased patronage of the arts — led to the further development of many art forms, including those of clothing. Genroku culture was spearheaded by the growing and increasingly-powerful merchant classes (chōnin); the clothing of chōnin classes, representative of their increasing economic power, rivalled that of the aristocracy and samurai classes, brightly-coloured and utilising expensive production techniques, such as handpainted dyework. Rinzu, a damask fabric, also became the preferred material for kimono at this time, replacing the previously-popular nerinuki plain-weave silk, which had been used to create tsujigahana.[26]

In response to the increasing material wealth of the merchant classes, the Tokugawa shogunate issued a number of sumptuary laws `for the lower classes, prohibiting the use of purple or red fabric, gold embroidery, and the use of intricately dyed shibori patterns.[27] As a result, a school of aesthetic thought known as iki, which valued and prioritised the display of wealth through almost mundane appearances, developed, a concept of kimono design and wear that continues to this day as a major influence.

From this point onwards, the basic shape of both men’s and women’s kimono remained largely unchanged.[12] The sleeves of the kosode began to grow in length, especially amongst unmarried women, and the obi became much longer and wider, with various styles of knots coming into fashion, alongside stiffer weaves of material to support them.[12]

In the Edo period, the kimono market was divided into craftspeople, who made the tanmono and accessories, tonya, or wholesalers, and retailers.[7]: 129

Modern period (1869–), by regnal era[edit]

Meiji period (1868–1912)[edit]

-

Part of the Ootuki family in kimono, 1874

-

Assorted types of kimono, Western dress, a court lady in keiko, and a schoolgirl in a high-collared shirt, kimono and hakama. All wear both purple and red. 1890.

In 1869, the social class system was abolished, and with them, class-specific sumptuary laws.[7]: 113 Kimono with formerly-restricted elements, like red and purple colours, became popular,[7]: 147 particularly with the advent of synthetic dyestuffs such as mauvine.

Following the opening of Japan’s borders in the early Meiji period to Western trade, a number of materials and techniques — such as wool and the use of synthetic dyestuffs — became popular, with casual wool kimono being relatively common in pre-1960s Japan; the use of safflower dye (beni) for silk linings fabrics (known as momi; literally, «red silk») was also common in pre-1960s Japan, making kimono from this era easily identifiable.

During the Meiji period, the opening of Japan to Western trade after the enclosure of the Edo period led to a drive towards Western dress as a sign of «modernity». After an edict by Emperor Meiji,[citation needed] policemen, railroad workers and teachers moved to wearing Western clothing within their job roles, with the adoption of Western clothing by men in Japan happening at a much greater pace than by women. Initiatives such as the Tokyo Women’s & Children’s Wear Manufacturers’ Association (東京婦人子供服組合) promoted Western dress as everyday clothing.

In Japan, modern Japanese fashion history might be conceived as a gradual westernization of Japanese clothes; both the woolen and worsted industries in Japan originated as a product of Japan’s re-established contact with the West in the early Meiji period (1850s-1860s). Before the 1860s, Japanese clothing consisted entirely of kimono of a number of varieties.[citation needed]

With the opening of Japan’s ports for international trade in the 1860s, clothing from a number of different cultures arrived as exports; despite Japan’s historic contact with the Dutch before this time through its southerly ports, Western clothing had not caught on, despite the study of and fascination with Dutch technologies and writings.

The first Japanese to adopt Western clothing were officers and men of some units of the shōgun’s army and navy; sometime in the 1850s, these men adopted woolen uniforms worn by the English marines stationed at Yokohama. Wool was difficult to produce domestically, with the cloth having to be imported. Outside of the military, other early adoptions of Western dress were mostly within the public sector, and typically entirely male, with women continuing to wear kimono both inside and outside of the home, and men changing into the kimono usually within the home for comfort.[28]

From this point on, Western clothing styles spread outwards of the military and upper public sectors, with courtiers and bureaucrats urged to adopt Western clothing, promoted as both modern and more practical. The Ministry of Education ordered that Western-style student uniforms be worn in public colleges and universities. Businessmen, teachers, doctors, bankers, and other leaders of the new society wore suits to work and at large social functions. Despite Western clothing becoming popular within the workplace, in schools and on the streets, it was not worn by everybody, and was actively considered uncomfortable and undesirable by some; one account tells of a father promising to buy his daughters new kimono as a reward for wearing Western clothing and eating meat.[29] By the 1890s, appetite for Western dress as a fashion statement had cooled considerably, and the kimono remained an item of fashion.

A number of different fashions from the West arrived and were also incorporated into the way that people wore kimono; numerous woodblock prints from the later Meiji period show men wearing bowler hats and carrying Western-style umbrellas whilst wearing kimono, and Gibson girl hairstyles — typically a large bun on top of a relatively wide hairstyle, similar to the Japanese nihongami — became popular amongst Japanese women as a more low-effort hairstyle for everyday life.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Western dress had become a symbol of social dignity and progressiveness; however, the kimono was still considered to be fashion, with the two styles of dress essentially growing in parallel with one another over time. With Western dress being considered street wear and a more formal display of fashionable clothing, most Japanese people wore the comfortable kimono at home and when out of the public eye.[28]

Taishō period (1912–1926)[edit]

Western clothing quickly became standard issue as army uniform for men[30] and school uniform for boys, and between 1920 and 1930, the fuku sailor outfit replaced the kimono and undivided hakama as school uniform for girls.[12]: 140 However, kimono still remained popular as an item of everyday fashion; following the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, cheap, informal and ready-to-wear meisen kimono, woven from raw and waste silk threads unsuitable for other uses, became highly popular, following the loss of many people’s possessions.[31] By 1930, ready-to-wear meisen kimono had become highly popular for their bright, seasonally changing designs, many of which took inspiration from the Art Deco movement. Meisen kimono were usually dyed using the ikat (kasuri) technique of dyeing, where either warp or both warp and weft threads (known as heiyō-gasuri)[31]: 85 were dyed using a stencil pattern before weaving.

It was during the Taishō period that the modern formalisation of kimono and kimono types began to emerge. The Meiji period had seen the slow introduction of kimono types that mediated between the informal and the most formal, a trend that continued throughout the Taishō period, as social occasions and opportunities for leisure increased under the abolition of class distinctions. As Western clothing increased in popularity for men as everyday clothing, the kimono industry further established its own traditions of formal and informal dress for women; this saw the invention of the hōmongi, divisions of tomesode (short-sleeved) kimono for women, and montsuki hakama.[7]: 133-134 The bridal kimono trousseau (oyomeiri dōgu), an uncommon practice of the upper classes in the Edo period, also became common throughout the middle classes;[7]: 67, 76 traditions of kimono bridalwear for marriage ceremonies were also codified in this time, which resembled the bridalwear of samurai-class women.[7]: 82, 93, 146 Standards of kitsuke at this time began to slowly graduate to a more formalised, neatened appearance, with a flat, uniform ohashori and a smooth, uncreased obi, which also resembled the «proper» kitsuke of upper-class women. However, kitsuke standards were still relatively informal, and would not become formalised until after World War II.

Shōwa period (1926–1989)[edit]

A 1957 clothing ad, showing postwar kitsuke standards for women, which promoted a smooth, streamlined appearance.

While kimono were no longer common wear for men, they remained everyday wear for Japanese women until World War II (1940–1945).[7]: 17 Though the Taishō period had seen a number of invented traditions, standards of kitsuke (wearing kimono) were still not as formalised in this time, with creases, uneven ohashori and crooked obi still deemed acceptable.[7]: 44-45

Until the 1930s, the majority of Japanese still wore kimono, and Western clothes were still restricted to out-of-home use by certain classes.[28]

During the war, kimono factories shut down, and the government encouraged people to wear monpe (also romanised as mompe) — trousers constructed from old kimono — instead.[7]: 131 Fibres such as rayon became widespread during WWII, being inexpensive to produce and cheap to buy, and typically featured printed designs.[citation needed] Cloth rationing persisted until 1951, so most kimono were made at home from repurposed fabrics.[7]: 131

In the second half of the 20th century, the Japanese economy boomed,[7]: 36 and silk became cheaper,[citation needed] making it possible for the average family to afford silk kimono.[7]: 76 The kimono retail industry had developed an elaborate codification of rules for kimono-wearing, with types of kimono, levels of formality, and rules on seasonality, which intensified after the war; there had previously been rules about kimono-wearing, but these were not rigidly codified and varied by region and class.[7]: 36 Formalisation sought perfection, with no creases or uneveness in the kimono, and an increasingly tubular figure was promoted as the ideal for women in kimono.[7]: 44-45 The kimono-retail industry also promoted a sharp distinction between Japanese and Western clothes;[7]: 54 for instance, wearing Western shoes with Japanese clothing (while common in the Taishō period) was codified as improper;[7]: 16 these rules on proper dressing are often described in Japanese using the English phrase «Time, Place, and Occasion» (TPO). As neither Japanese men or women commonly wore kimono, having grown up under wartime auspices, commercial kitsuke schools were set up to teach women how to don kimono.[7]: 44 Men in this period rarely wore kimono, and menswear thus escaped most of the formalisation.[7]: 36, 133 ).

Kimono were promoted as essential for ceremonial occasions;[7]: 76, 135 for instance, the expensive furisode worn by young women for Seijinshiki was deemed a necessity.[7]: 60 Bridal trousseaus containing tens of kimono of every possible subtype were also promoted as de rigueur, and parents felt obliged to provide[7]: 76 kimono trousseaus that cost up to 10 million yen (~£70,000),[7]: 262 which were displayed and inspected publicly as part of the wedding, including being transported in transparent trucks.[7]: 81

By the 1970s, formal kimono formed the vast majority of kimono sales.[7]: 132 Kimono retailers, due to the pricing structure of brand new kimono, had developed a relative monopoly on not only prices but also a perception of kimono knowledge, allowing them to dictate prices and heavily promote more formal (and expensive) purchases, as selling a single formal kimono could support the seller comfortably for three months. The kimono industry peaked in 1975, with total sales of 2.8 trillion yen (~£18 billion). The sale of informal brand new kimono was largely neglected.[7]: 135, 136

Heisei period (1989–2019)[edit]

A young woman wearing very formal Japanese dress, 2010; note the katsuyama-style nihongami wig with attached locks and numerous kanzashi, paired with a formal brocade uchikake overkimono.

The economic collapse of the 1990s bankrupted much of the kimono industry[7]: 129 and ended a number of expensive practices.[7]: 98 The rules for how to wear kimono lost their previous hold over the entire industry,[7]: 36 and formerly-expensive traditions such as bridal kimono trousseaus generally disappeared, and when still given, were much less extensive.[7]: 98 It was during this time that it became acceptable and even preferred for women to wear Western dress to ceremonial occasions like weddings and funerals.[7]: 95, 263 Many women had dozens or even hundreds of kimono, mostly unworn, in their homes; a secondhand kimono, even if unworn, would sell for about 500 yen (less than £3.50;[7]: 98 about US$5), a few percent of the bought-new price. In the 1990s and early 2000s, many secondhand kimono shops opened as a result of this.[7]: 98

In the early years of the 21st century, the cheaper and simpler yukata became popular with young people.[7]: 37 Around 2010, men began wearing kimono again in situations other than their own wedding,[7]: 36, 159 and kimono were again promoted and worn as everyday dress by a small minority.[7]

Reiwa period (2019–present)[edit]

Today, the vast majority of people in Japan wear Western clothing in the everyday, and are most likely to wear kimono either to formal occasions such as wedding ceremonies and funerals, or to summer events, where the standard kimono is the easy-to-wear, single-layer cotton yukata.

Types of traditional clothing[edit]

Kimono[edit]

Gion geisha Sayaka wearing a kurotomesode

The kimono (着物), labelled the «national costume of Japan»,[1] is the most well-known form of traditional Japanese clothing. The kimono is worn wrapped around the body, left side over right, and is sometimes worn layered. It is always worn with an obi, and may be worn with a number of traditional accessories and types of footwear.[32] Kimono differ in construction and wear between men and women.

After the four-class system ended in the Tokugawa period (1603-1867), the symbolic meaning of the kimono shifted from a reflection of social class to a reflection of self, allowing people to incorporate their own tastes and individualize their outfit.[vague] The process of wearing a kimono requires, depending on gender and occasion, a sometimes detailed knowledge of a number of different steps and methods of tying the obi, with formal kimono for women requiring at times the help of someone else to put on. Post-WW2, kimono schools were built to teach those interested in kimono how to wear it and tie a number of different knots.[1]

Japanese Woman in Traditional Dress Posing Outdoors by Suzuki Shin’ichi, c. 1870s

A number of different types of kimono exist that are worn in the modern day, with women having more varieties than men. Whereas men’s kimono differ in formality typically through fabric choice, the number of crests on the garment (known as mon or kamon) and the accessories worn with it, women’s kimono differ in formality through fabric choice, decoration style, construction and crests.

Women’s kimono[edit]

- The furisode (lit., «swinging sleeve») is a type of formal kimono usually worn by young women, often for Coming of Age Day or as bridalwear, and is considered the most formal kimono for young women.

- The uchikake is also worn as bridalwear as an unbelted outer layer.

- The kurotomesode and irotomesode are formal kimono with a design solely along the hem, and are considered the most formal kimono for women outside of the furisode.

- The houmongi and the tsukesage are semi-formal women’s kimono featuring a design on part of the sleeves and hem.

- The iromuji is a low-formality solid-colour kimono worn for tea ceremony and other mildly-formal events.

- The komon and edo komon are informal kimono with a repeating pattern all over the kimono.

Other types of kimono, such as the yukata and mofuku (mourning) kimono are worn by both men and women, with differences only in construction and sometimes decoration. In previous decades, women only stopped wearing the furisode when they got married, typically in their early- to mid-twenties; however, in the modern day, a woman will usually stop wearing furisode around this time whether she is married or not.[32]

Dressing in kimono[edit]

The word kimono literally translates as «thing to wear», and up until the 19th century it was the main form of dress worn by men and women alike in Japan.[33]