Автор: Денис Усачев

Приходилось ли вам слышать, что «Мой сосед Тоторо» ― мультик красивый, но с мрачным подтекстом»?

Если да, то это статья для вас, если нет ― тем более. Думаю, вы многое переосмыслите в своем понимании японской анимации.

Если вы не знаете, кто такой Хаяо Миядзаки, вы ничего не знаете о японской анимации. Человек, имя которого не просто синоним самой анимации, но и целая эпоха. Имя этого человека звучит по миру так же громко, как и Стэна Ли, на протяжении более 30 лет с момента выхода полнометражного анимационного фильма «Мой сосед Тоторо». Фильма, который входит в «Топ-250 фильмов всех времен» наряду с «Унесенными призраками» и «Ходячим замком» того же Миядзаки.

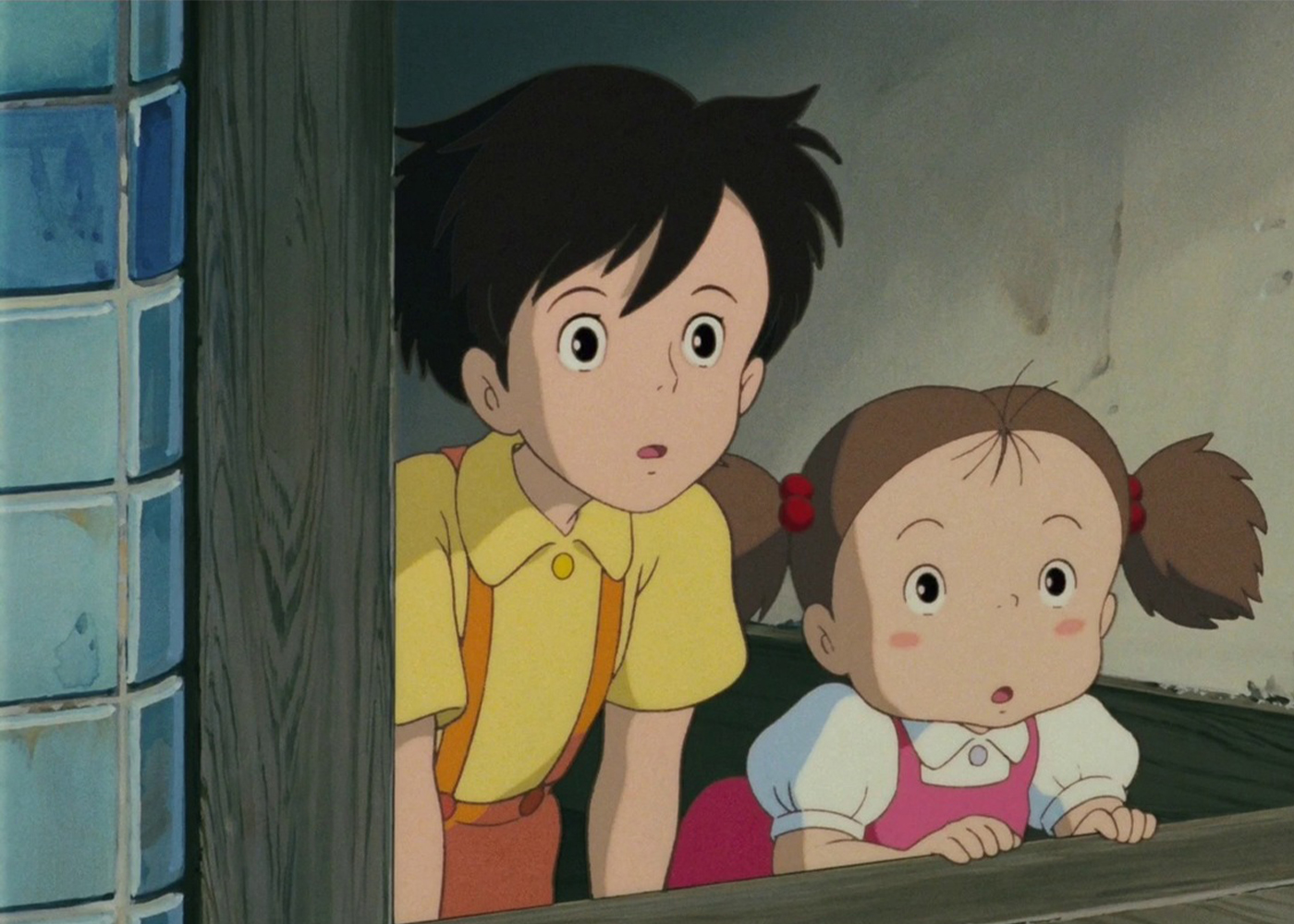

В чем же секрет популярности этого аниме? Казалось бы, это сказка о двух сестрах, встретивших странное существо ― духа-хранителя леса Тоторо ― и подружившихся с ним. Но все ли так просто? Попробуем разобраться, если не во всем, то, по крайней мере, в части смысла, скрытого от поверхностного просмотра.

«В общем, все умерли». Теории фанатов

Главная теория об этом фильме заключается в том, что история о двух девочках основана на реальности. 1 мая 1963 года в Саяме, той области, где происходит действие фильма, маньяк жестоко убил 16-летнюю девушку, а ее сестра после покончила с собой. Давайте разберемся, какое отношение кроме места эта история имеет к фильму и имеет ли вообще?

Сестер в фильме зовут одинаково. Сацуки, что в Японии соответствует маю, и Мэй, что означает «май» по-английски. По словам самого Миядзаки, это связано с тем, что изначально девочка должна была быть одна, но в последний момент было принято решение ввести еще и сестру, которой имя менять не стали.

Действие фильма происходит в 1958 году, что можно заметить по развешанным на заднем плане календарям, а также ежедневникам. Старшей сестре 11 лет, то есть в 1963 году ей будет 16.

По версии фанатов, последние 10 минут фильма сестры не отбрасывают теней, что означает, что они умерли. Почему по версии? Если вы внимательно посмотрите фильм, вы заметите, что тени все-таки есть, так что этот аргумент отбрасываем.

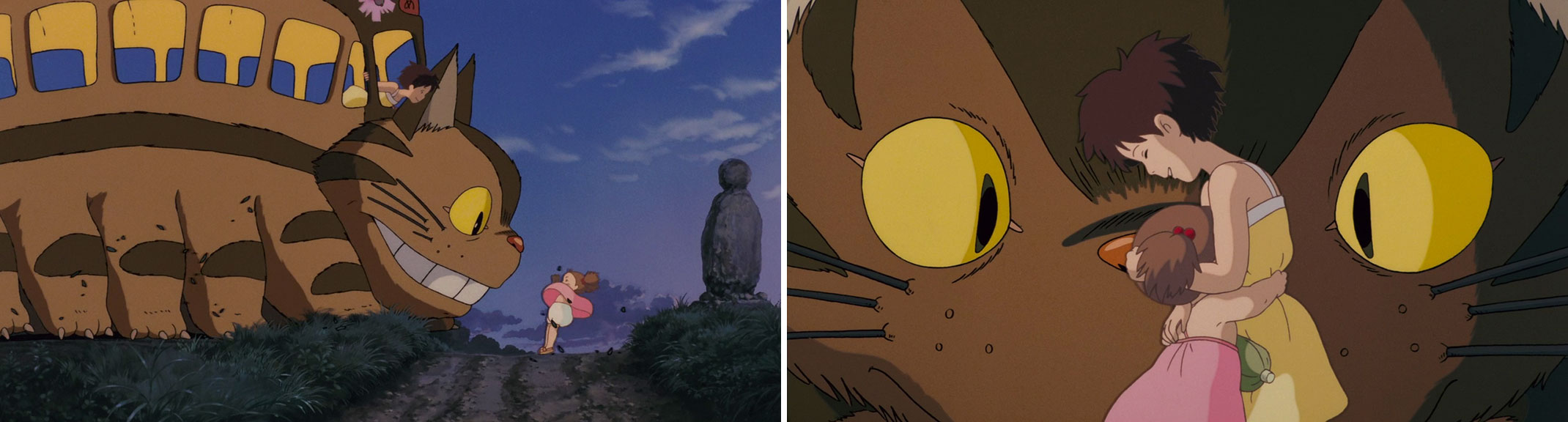

Когда Котобус меняет названия пункта назначения на Мэй, прямо перед ее именем следует название «Могильная дорога», что можно трактовать как кладбище, то есть Мэй именно там или чуть дальше.

Когда Сацуки находит Мэй, та сидит возле шести статуй Дзидзо — это божество Японии, покровитель путешественников и душ умерших детей. Статуй, по версии фанатов, должно быть семь, а их шесть, что означает, что Мэй ― седьмая, то есть она мертва. Этот аргумент тоже не состоятелен, так как в японской легенде о статуях Дзидзо их именно шесть.

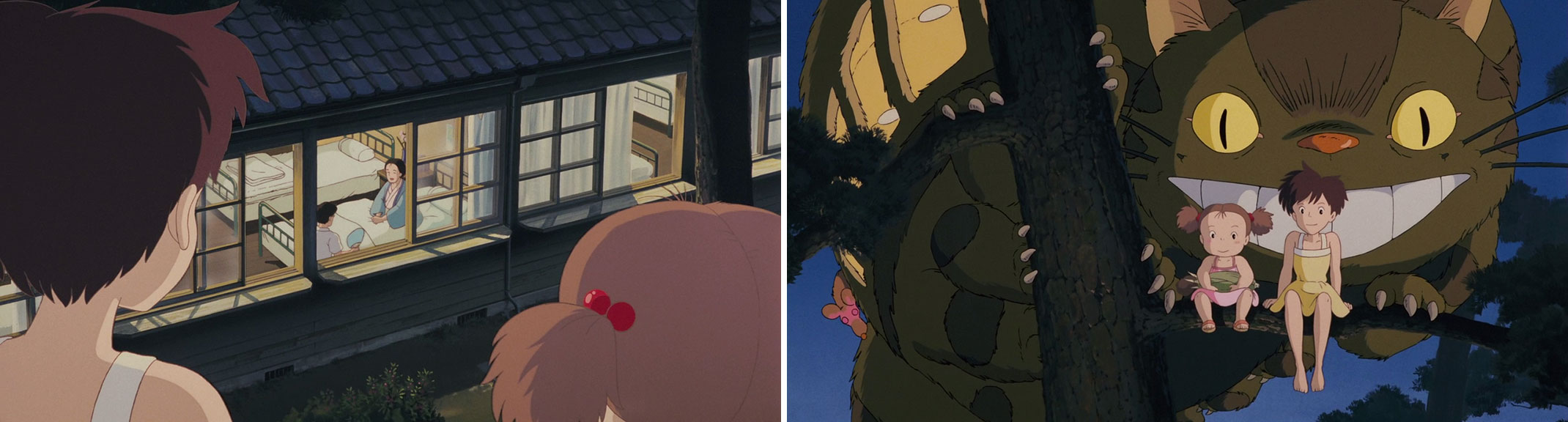

Маме кажется, что она видит детей в ветвях дерева за окном, а кукурузу они оставляют как призраки, незаметно, с прощальной надписью. Чтобы это объяснить, нужно понимать, что взрослые не видят духов и Котобуса, он может оставаться невидимым по своему желанию, а значит, и делает невидимыми девочек.

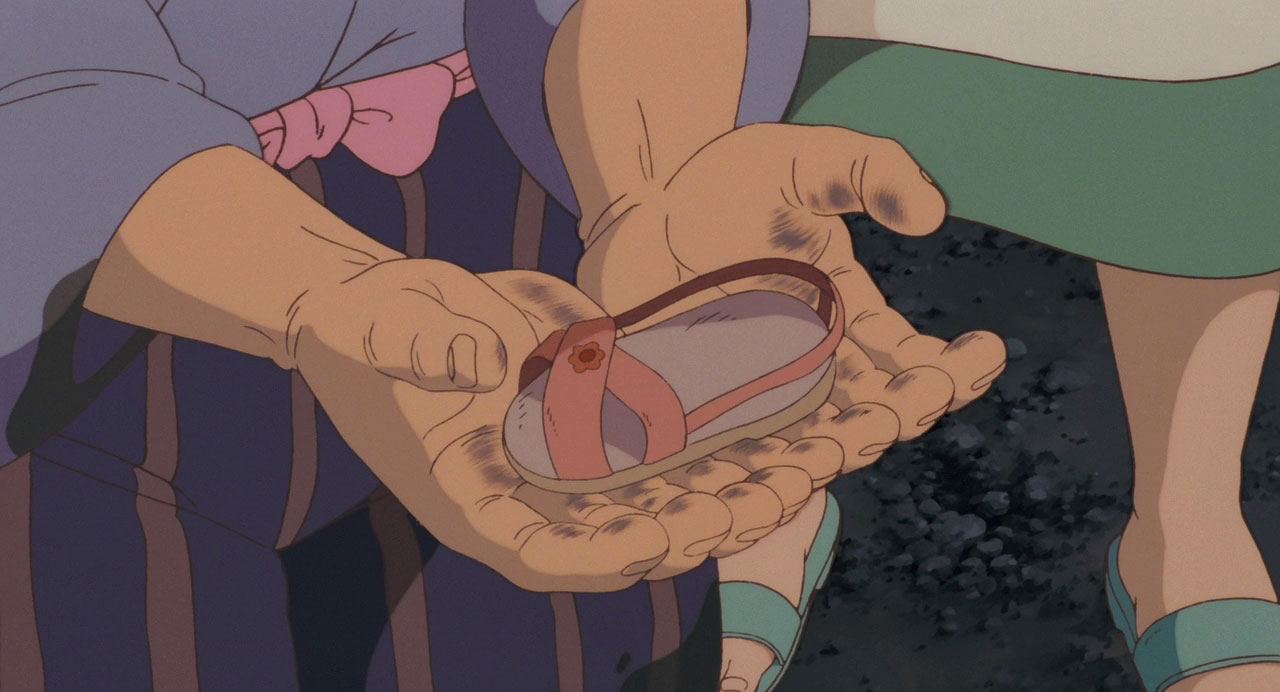

Версию о мрачном подтексте «Моего соседа Тоторо» студия Гибли отрицает до сих пор, однако есть множество оснований считать, что эта история не столько основана на трагедии Саямы, сколько является данью уважения памяти убитых девушек, переосмыслением их истории со счастливым финалом. В пользу этого говорит и сандалик, найденный в пруду, оказавшийся не вещью Мэй, но это ведь чья-то вещь?

Но, несмотря на мрачный контекст фильма, Тоторо все равно остается одним из самых ярких и красивых детских воспоминаний. Это великолепный сплав сказки и правды жизни, представленной через взгляд ребенка.

Тайный смысл и отсылки

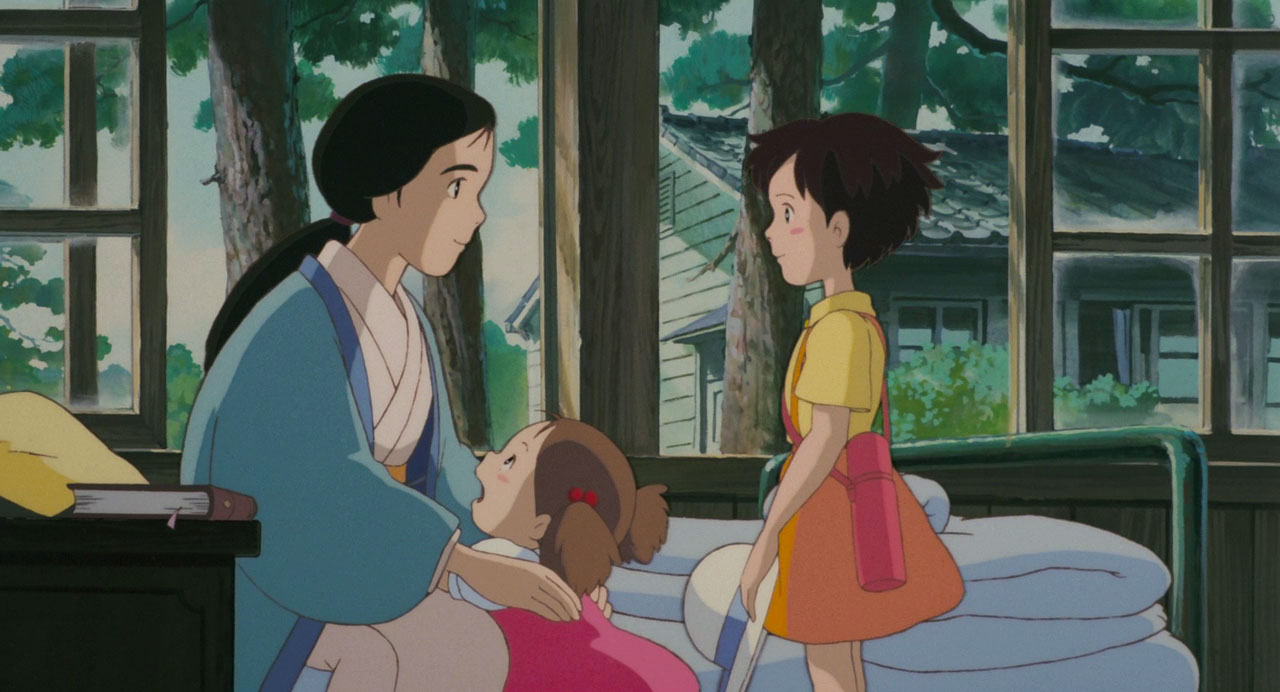

Семья Кусакабэ переезжает в деревню, чтобы быть ближе к лучшей больнице, где лечится мать девочек. Она больна туберкулезом и больна уже давно. Это отсылка к детству самого Миядзаки, чья мать также долго болела туберкулезом, отчего их семье много приходилось переезжать.

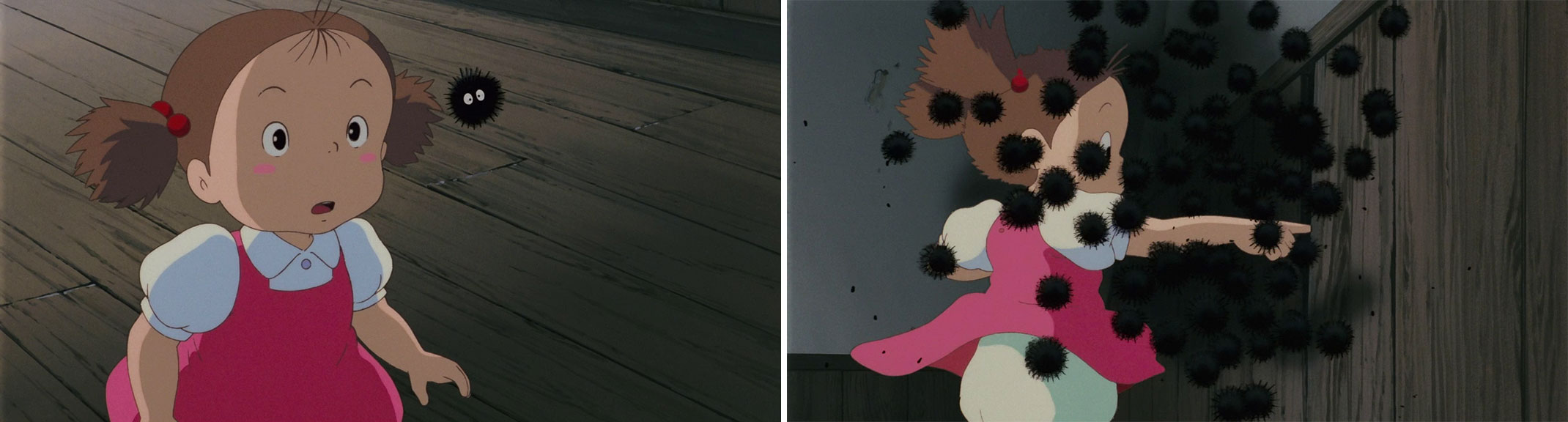

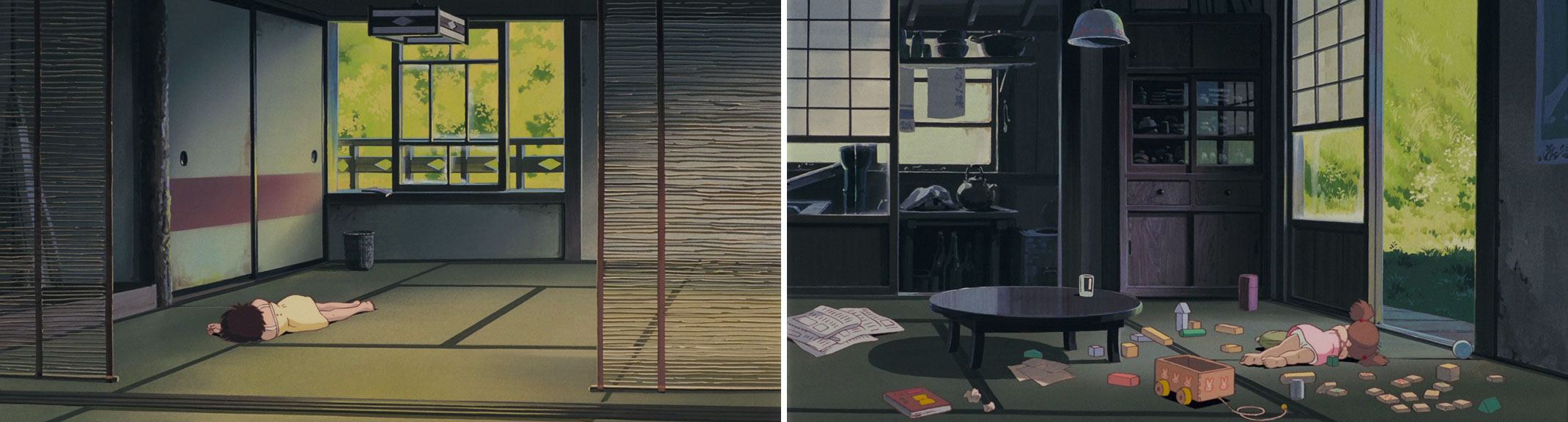

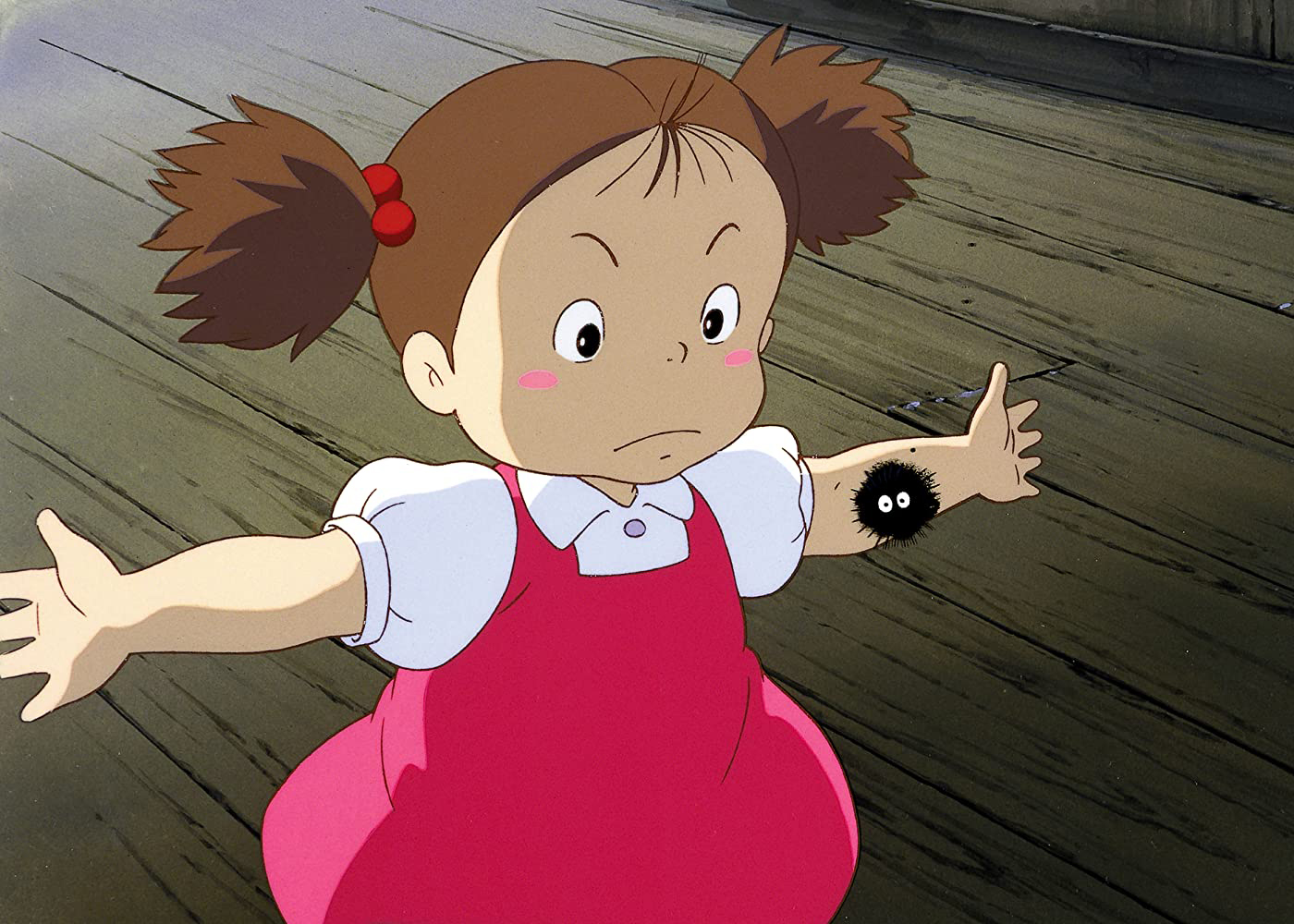

Старый дом, который чуть ли не на глазах разваливается, скрывает в себе призраков, сусуватари, маленьких черных пушистиков, которые покрывают старые дома сажей и копотью. Они не злые, но видеть их могут только дети. Этих существ придумал сам Миядзаки, как и множество образов этого и прочих своих фильмов. Они еще встретятся нам на экранах в оскароносных «Унесенных призраками».

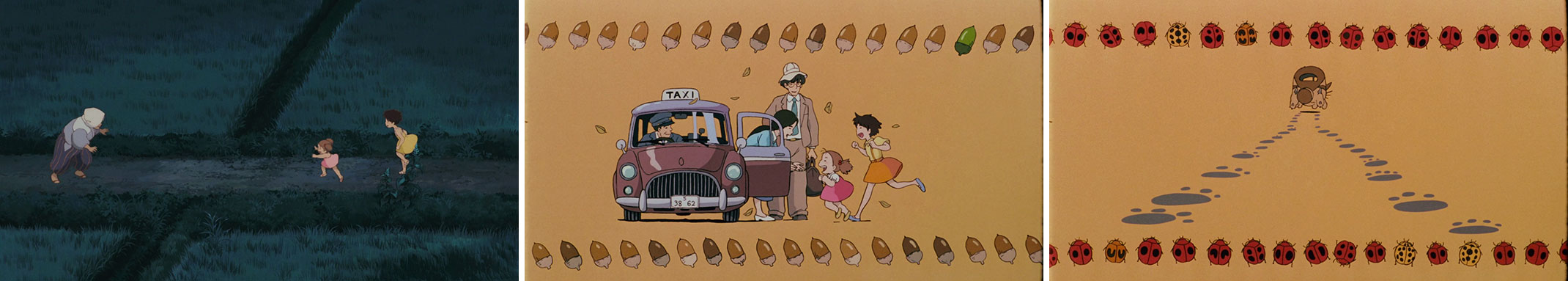

В доме также находятся желуди, падающие с потолка. Это символ плодородия и самой жизни, таких символов в фильме множество: рис, кукуруза, семена, ростки, мировое древо ― именно они наполняют фильм сочными красками, а нас ― верой в жизнь и природные силы.

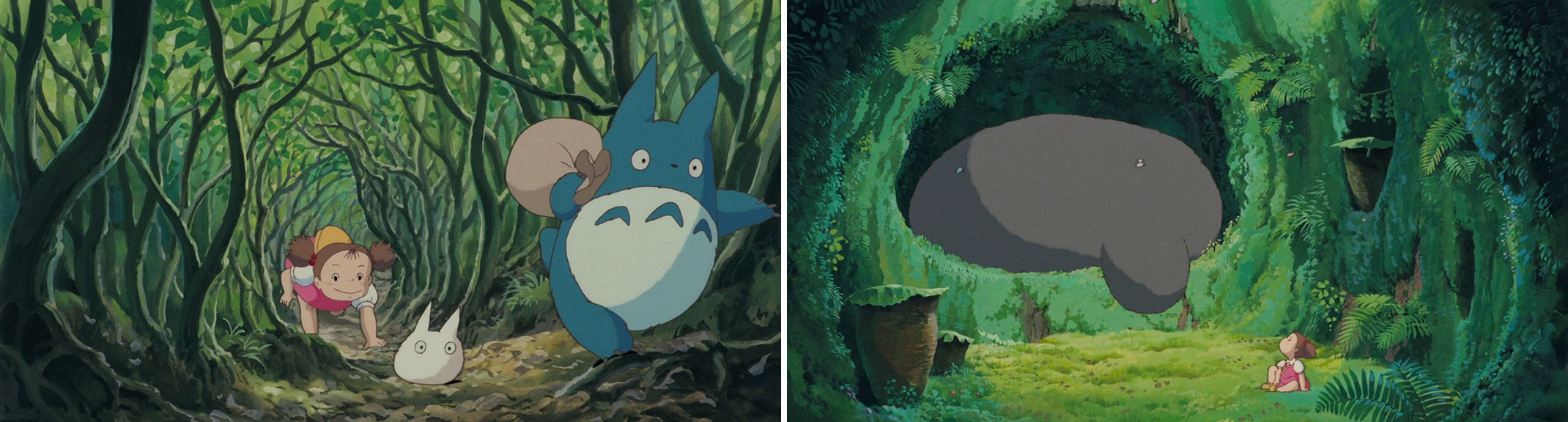

Желуди приводят младшую сестру Мэй к тоннелю в кустах, она бежит сквозь него за двумя маленькими тоторо, а потом падает в дупло дерева и, подобно Алисе в Стране чудес, попадает в мир духов, встречая О-Тоторо ― самого большого и главного. Вообще отсылок к Алисе в этом фильме много. Самая яркая из них – Котобус. Такая улыбка может быть только у Чеширского кота, который также умеет растворяться в воздухе.

Кто такой Тоторо?

Начнем с того, что никакого существа в таком обличии и с таким именем в японском фольклоре нет, его полностью придумал Миядзаки. Он похож на тануки (енотовидные собаки ― фантастические обитатели леса), ушами и глазами напоминает кота, много общего у него и с совой (он издает ухающие звуки и может даже летать).

Тоторо — это воплощение леса, его Хранитель. Для верований японцев характерна вера в ками ― божеств, населяющих наш мир. Они живут в камнях, деревьях, ручьях. У каждого леса, реки и горы есть свои Хранитель. Это могущественное существо, которое охраняет свои владения от зла, в том числе людей, что можно более подробно увидеть в другом знаменитом шедевре Миядзаки «Принцесса Мононоке».

Выглядят они по-разному, и один из них Тоторо. Его имя тоже особенно, это не японское слово, а искаженный вариант японского аналога слова тролль («totoru»). Из-за картавости, что можно четко услышать в оригинальной озвучке, Мэй произносит это слово с ошибкой. Тоторо не тролль в привычном нам понимании, но Мэй он напомнил персонажа ее любимой книжки, о чем она и говорит сестре.

Книжку эту можно увидеть в самом конце, ее выздоровевшая мама читает дочкам на ночь. «Три козлика и тролль» ― так называется эта сказка. В фильме есть множество подсказок, что Тоторо ― персонаж этой сказки. Сацуки все время проходит по мостам. При первом знакомстве с деревней, она смотрит с моста вниз, а мы помним, что тролли живут под мостами. Но Тоторо не тролль, он просто мистическое существо, то, что стоит за спиной.

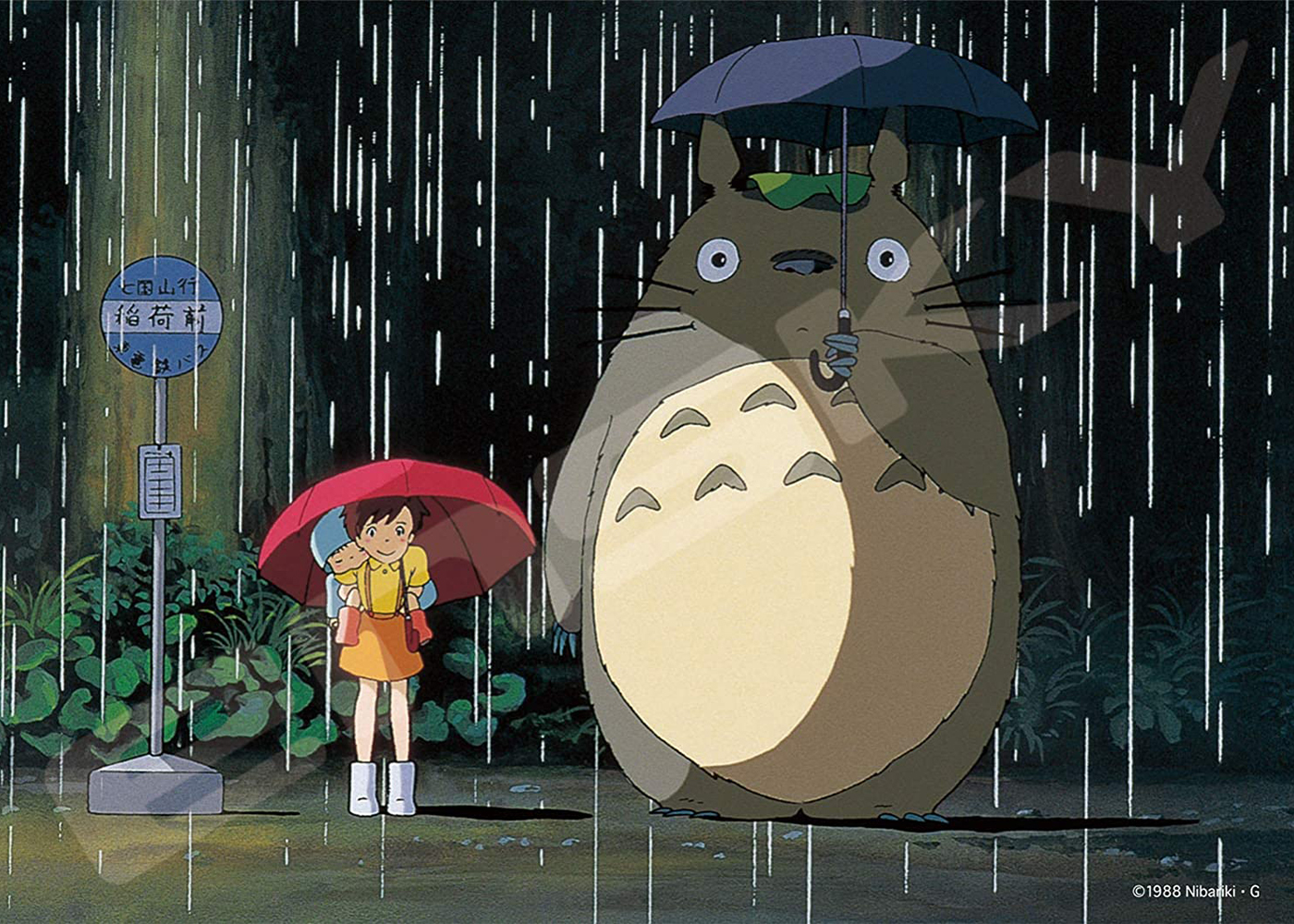

Ключевой сценой фильма является встреча Сацуки и Тоторо под дождем на остановке. Это самая запоминающаяся и яркая сцена. Первоначальное название этого фильма было Tonari ni iru Obake, что в переводе означает «Призрак у меня за спиной». Именно так, по словам Миядзаки, ему пришла идея Тоторо, когда он стоял так же на остановке и ждал автобуса. Что стоит у нас за спиной в темноте под дождем? Может быть, дружелюбный сосед Тоторо?

Скрытые символы

Зонт ― важная часть фильма. В японской мифологии зонт ― символ защиты от злых духов. Кента, маленький мальчик, увлекающийся самолетами, прямо как сам Миядзаки в детстве, вручает свой зонт сестрам, когда они попадают под дождь и молятся Дзидзо, покровителю детей, в результате чего они получают защиту.

Позже Сацуки вручает зонт своего отца Тоторо, у которого тот вызывает восторг. Это подтверждает, что Тоторо ― добрый дух, который защитит и не обидит девочек, поможет им в беде. Примечательно, что каждая из сестер встречается с Тоторо трижды, словно три желания в сказках, но на самом деле желание Тоторо исполняет лишь одно ― помогает найти Мэй.

Семена, которые Тоторо дарит сестрам, а потом помогает вырастить из них во сне девочек Мировое древо, символ плодородия и победы жизни, мы уже упоминали, но важна также символика полета Тоторо и сестер. Они летят на японском волчке, бэигоме, который дети во время игры запускают с веревки, летят с ветром при помощи зонта. Никого не напоминает? Правильно, Мэри Поппинс, знаменитая английская няня, которая очень любила и воспитывала детей, по сути, такой же покровитель и защитник, как Дзидзо и Тоторо.

Стоит отметить, что Миядзаки изучал в институте детскую литературу, причем именно европейскую, так что внимательный зритель может увидеть множество отсылок к знаменитым творениям детских писателей. Такой великолепный сплав европейской и азиатской мифологий не может оставить равнодушным никого в мире.

Вклад в культуру Японии

«Мой сосед Тоторо» — это добрая сказка, полная веры в природу и в саму жизнь. Что символично, в фильме вообще нет зла, нет привычного нам противостояния, есть только доброта и бесконечная любовь к природе и людям. Это не просто фильм, вошедший в сокровищницу мирового кинематографа. Это аниме повлияло на умы многих людей. Действие в фильме происходит в деревне Токородзава. Миядзаки любовно воспроизвел всю красоту этого места на экране.

Сейчас это район Токио. Он застроен серыми безликими зданиями, где, казалось бы, нет места деревьям, лесу, а значит, и Тоторо. Но нет! Существует национальное движение «Дом Тоторо», они пытаются сохранить остатки былой красоты и часть того леса, где живет Тоторо.

В Токородзаве сохранились природоохранные зоны, а лес Фути-но-Мори, который принято называть «Лесом Тоторо», сохранен благодаря любителям этого аниме и самому Миядзаки: он уже много лет вкладывает личные средства в поддержание чистоты в этом лесу, сам руководит соответствующим комитетом и ежегодно устраивает большой субботник по его уборке.

Трудно переоценить вклад, внесенный Тоторо в культуру Японии и всего мира, не зря Тоторо ― символ студии Гибли, которой принадлежат еще многие шедевры японской анимации. Среди них и «Унесенные призраками» ― самое популярное и известное аниме во всем мире. Интересных отсылок и моментов там великое множество, но об этом как-нибудь в другой раз…

| My Neighbor Totoro | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Japanese theatrical release poster |

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | となりのトトロ | ||

|

|||

| Directed by | Hayao Miyazaki | ||

| Written by | Hayao Miyazaki | ||

| Produced by | Toru Hara | ||

| Starring |

|

||

| Cinematography | Hisao Shirai | ||

| Edited by | Takeshi Seyama | ||

| Music by | Joe Hisaishi | ||

|

Production |

Studio Ghibli |

||

| Distributed by | Toho | ||

|

Release date |

|

||

|

Running time |

86 minutes | ||

| Country | Japan | ||

| Language | Japanese | ||

| Box office | $41 million |

My Neighbor Totoro (Japanese: となりのトトロ, Hepburn: Tonari no Totoro, lit. ‘Neighbour of Totoro’) is a 1988 Japanese animated fantasy film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki and animated by Studio Ghibli for Tokuma Shoten. The film—which stars the voice actors Noriko Hidaka, Chika Sakamoto, and Hitoshi Takagi—tells the story of a professor’s two young daughters (Satsuki and Mei) and their interactions with friendly wood spirits in postwar rural Japan.

In 1989, Streamline Pictures produced an English-language dub for exclusive use on transpacific flights by Japan Airlines. Troma Films, under their 50th St. Films banner, distributed the dub of the film co-produced by Jerry Beck. This dub was released to United States theaters in 1993, on VHS and LaserDisc in the United States by Fox Video in 1994, and on DVD in 2002. The rights to this dub expired in 2004, so the film was re-released by Walt Disney Home Entertainment on March 7, 2006[1] with a new dub cast. This version was also released in Australia by Madman on March 15, 2006[2] and in the UK by Optimum Releasing on March 27, 2006. This DVD release is the first version of the film in the United States to include both Japanese and English language tracks.

Exploring themes such as animism, Shinto symbology, environmentalism and the joys of rural living, My Neighbor Totoro received worldwide critical acclaim and has amassed a global cult following in the years after its release. The film has grossed over $41 million at the worldwide box office as of September 2019, in addition to generating an estimated $277 million from home video sales and $1.142 billion from licensed merchandise sales, adding up to approximately $1.46 billion in total lifetime revenue.

My Neighbor Totoro received numerous awards, including the Animage Anime Grand Prix prize, the Mainichi Film Award and Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film in 1988. It also received the Special Award at the Blue Ribbon Awards in the same year. The film is considered as one of the top animation films, ranking 41st in Empire magazine’s «The 100 Best Films of World Cinema» in 2010 and being the highest-ranking animated film on the 2012 Sight & Sound critics’ poll of all-time greatest films.[3][4] The film and its titular character have become cultural icons and made multiple cameo appearances in a number of Studio Ghibli films and video games. Totoro also serves as the mascot for the studio and is recognized as one of the most popular characters in Japanese animation.

Plot[edit]

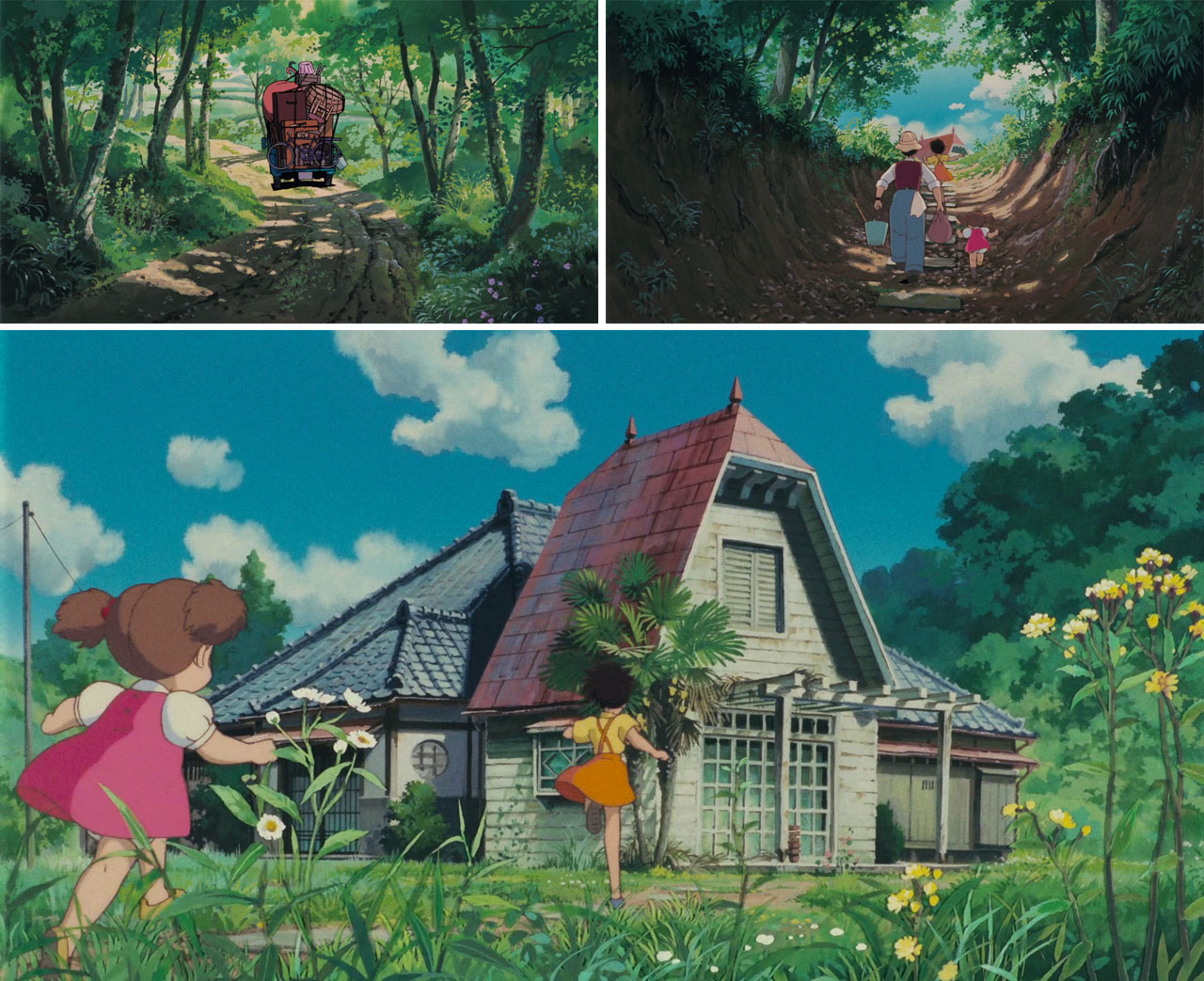

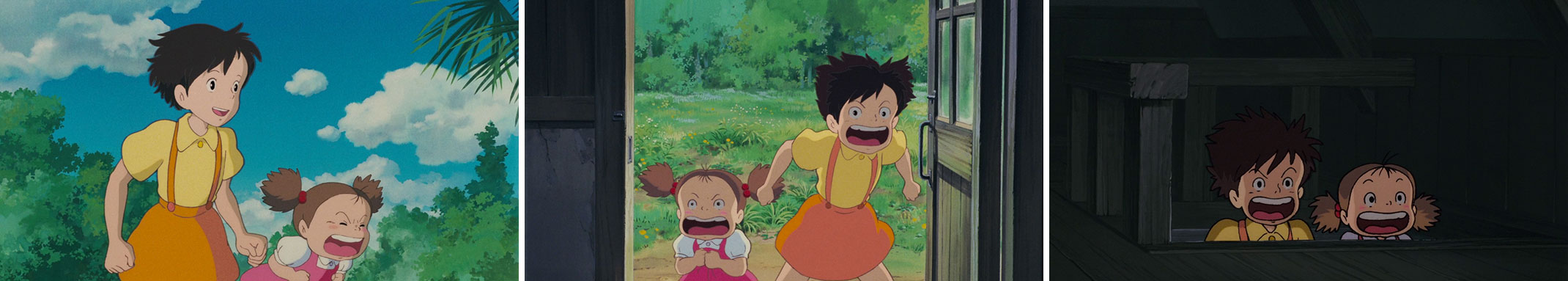

In 1950s Japan, university professor Tatsuo Kusakabe and his two daughters, Satsuki and Mei (approximately ten and four years old, respectively), move into an old house closer to the hospital where the girls’ mother, Yasuko, is recovering from a long-term illness. The house is inhabited by small, dark, dust-like house spirits called susuwatari, which can be seen when moving from bright to dark places.[note 1] When the girls become comfortable in their new house, the susuwatari leave to find another empty house. One day, Mei discovers two small spirits who lead her into the hollow of a large camphor tree. She befriends a larger spirit, which identifies itself by a series of roars that she interprets as «Totoro». Mei thinks Totoro is the Troll from her illustrated book Three Billy Goats Gruff, with her mispronouncing Troll. She falls asleep atop Totoro, but when Satsuki finds her, she is on the ground. Despite many attempts, Mei cannot show her family Totoro’s tree. Tatsuo comforts her by telling her that Totoro will reveal himself when he wants to.

Closeup view of Satsuki and Mei’s house

One rainy night, the girls are waiting for Tatsuo’s bus, which is late. Mei falls asleep on Satsuki’s back, and Totoro appears beside them, allowing Satsuki to see him for the first time. Totoro has only a leaf on his head for protection against the rain, so Satsuki offers him the umbrella she had taken for her father. Delighted, he gives her a bundle of nuts and seeds in return. A giant, bus-shaped cat halts at the stop, and Totoro boards it and leaves. Shortly after, Tatsuo’s bus arrives. A few days after planting the seeds, the girls awaken at midnight to find Totoro and his colleagues engaged in a ceremonial dance around the planted seeds and join in, causing the seeds to grow into an enormous tree. Totoro takes the girls for a ride on a magical flying top. In the morning, the tree is gone, but the seeds have sprouted.

The girls discover that a planned visit by Yasuko has to be postponed because of a setback in her treatment. Mei does not take this well and argues with Satsuki, leaving for the hospital to bring fresh corn to Yasuko. Her disappearance prompts Satsuki and the neighbors to search for her. In desperation, Satsuki returns to the camphor tree and pleads for Totoro’s help. He delightfully summons the Catbus, which carries her to where the lost Mei sits, and the sisters emotionally reunite. The bus then takes them to the hospital. The girls overhear a conversation between their parents and learn that she has been kept in hospital by a minor cold but is otherwise doing well. They secretly leave the ear of corn on the windowsill, where their parents discover it, and return home. Eventually, Yasuko returns home, and the sisters play with other children while Totoro and his friends watch them from afar.

Characters[edit]

The name Totoro comes from a misprononciation of the word troll (トロール, torōru) by Mei. She has seen one in a book and decides that it must be the same creature.[5]

The cat-bus comes from a Japanese belief attributing to an old cat the power of shape-shifting: he then becomes a «bakeneko». The cat-bus is a «bakeneko» who has seen a bus and decided to become one.[5]

Themes[edit]

Animism is a large theme in this film according to Eriko Ogihara-Schuck.[6] Totoro has animistic traits and has kami status due to the fact that he lives in a camphor tree in a Shinto shrine surrounded by a Shinto rope and was referred to as «mori no nushi,» or «master of the forest».[6] Moreover, Ogihara-Schuck writes that when Mei returns from her encounter with Totoro her father takes Mei and her sister to the shrine to greet and thank Totoro. This is a common practice in the Shinto tradition following an encounter with a kami.[6] The themes of the film was additionally noted for Phillip E. Wegner, who believed the film as being an example of alternative history citing the utopian-like setting of the anime.[7]

Voice cast[edit]

| Character name | Japanese voice actor | English voice actor (Tokuma/Streamline/50th Street Films, 1989/1993) |

English voice actor (Walt Disney Home Entertainment, 2005) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satsuki Kusakabe (草壁 サツキ) (10-year-old daughter) | Noriko Hidaka | Lisa Michelson | Dakota Fanning |

| Mei Kusakabe (草壁 メイ) (4-year-old daughter) | Chika Sakamoto | Cheryl Chase | Elle Fanning |

| Tatsuo Kusakabe (草壁 タツオ) (father) | Shigesato Itoi | Greg Snegoff | Tim Daly |

| Yasuko Kusakabe (草壁 靖子) (mother) | Sumi Shimamoto | Alexandra Kenworthy | Lea Salonga |

| Totoro (トトロ) | Hitoshi Takagi | — | Frank Welker |

| Kanta Ōgaki (大垣 勘太) (a local boy) | Toshiyuki Amagasa | Kenneth Hartman | Paul Butcher |

| Granny (祖母) (Nanny in the 1993 dub) | Tanie Kitabayashi | Natalie Core | Pat Carroll |

| Catbus (ネコバス, Nekobasu) | Naoki Tatsuta | Carl Macek (uncredited) | Frank Welker |

| Michiko (ミチ子) | Chie Kōjiro | Brianne Siddall (uncredited) | Ashley Rose Orr |

| Mrs. Ogaki (Kanta’s mother) | Hiroko Maruyama | Melanie MacQueen | Kath Soucie |

| Mr. Ogaki (Kanta’s father) | Masashi Hirose | Steve Kramer | David Midthunder |

| Old Farmer | — | Peter Renaday | |

| Miss Hara (Satsuki’s teacher) | Machiko Washio | Edie Mirman (uncredited) | Tress MacNeille (uncredited) |

| Kanta’s Aunt | Reiko Suzuki | Russi Taylor | |

| Otoko | Daiki Nakamura | Kerrigan Mahan (uncredited) | Matt Adler |

| Ryōko | Yūko Mizutani | Lara Cody | Bridget Hoffman |

| Bus Attendant | — | Kath Soucie | |

| Mailman | Tomomichi Nishimura | Doug Stone (uncredited) | Robert Clotworthy |

| Moving Man | Shigeru Chiba | Greg Snegoff | Newell Alexander |

Production[edit]

We need a new method and sense of discovery to be up to the task. Rather than be sentimental, the film must be a joyful, entertaining film.

—Hayao Miyazaki[8]

Development[edit]

After working on 3000 Miles in Search of A Mother, Miyazaki conceptualised making a «delightful, wonderful film» that would be set in Japan with the idea to «entertain and touch its viewers, but stay with them long after they have left the theaters». Initially, Miyazaki had the main characters of Totoros, Mei, Tatsuo, Kanta.[8]: 8 The director conceptualised Mei on his niece,[9] and the Totoros as «serene, carefree creatures» that were «supposedly the forest keeper, but that’s only a half-baked idea, a rough approximation».[8]: 5, 103

Art director Kazuo Oga was drawn to the film when Hayao Miyazaki showed him an original image of Totoro standing in a satoyama. The director challenged Oga to raise his standards, and Oga’s experience with My Neighbor Totoro jump-started the artist’s career. Oga and Miyazaki debated the palette of the film, Oga seeking to paint black soil from Akita Prefecture and Miyazaki preferring the color of red soil from the Kantō region.[8]: 82 The ultimate product was described by Studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki: «It was nature painted with translucent colors.»[10]

Oga’s conscientious approach to My Neighbor Totoro was a style that the International Herald Tribune recognized as «[updating] the traditional Japanese animist sense of a natural world that is fully, spiritually alive». The newspaper described the final product:

Set in a period that is both modern and nostalgic, the film creates a fantastic, yet strangely believable universe of supernatural creatures coexisting with modernity. A great part of this sense comes from Oga’s evocative backgrounds, which give each tree, hedge and twist in the road an indefinable feeling of warmth that seems ready to spring into sentient life.[11]

Oga’s work on My Neighbor Totoro led to his continued involvement with Studio Ghibli. The studio assigned jobs to Oga that would play to his strengths, and Oga’s style became a trademark style of Studio Ghibli.[11]

In several of Miyazaki’s initial conceptual watercolors, as well as on the theatrical release poster and on later home video releases, only one young girl is depicted, rather than two sisters. According to Miyazaki, «If she was a little girl who plays around in the yard, she wouldn’t be meeting her father at a bus stop, so we had to come up with two girls instead. And that was difficult».[8]: 11 The opening sequence of the film was not storyboarded, Miyazaki said. «The sequence was determined through permutations and combinations determined by the time sheets. Each element was made individually and combined in the time sheets…»[8]: 27 The ending sequence depicts the mother’s return home and the signs of her return to good health by playing with Satsuki and Mei outside.[8]: 149

The storyboard depicts the town of Matsuko as the setting, with the year being 1955; Miyazaki stated that it was not exact and the team worked on a setting «in the recent past».[8]: 33 The film was originally set to be an hour long, but throughout the process it grew to respond to the social context including the reason for the move and the father’s occupation.[8]: 54 Eight animators worked on the film, which was completed in eight months.[12]

Tetsuya Endo noted numerous animation techniques that were utilised in the film. For example, the ripples were designed with «two colors of high-lighting and shading» and the rain for My Neighbor Totoro was «scratched in the cels» and superimposed for it to convey a softer feel.[8]: 156 The animators stated that one month was taken to create the tadpoles, which included four colours, the water for it was also blurred.[8]: 154

Music[edit]

The music for the film was composed by Joe Hisaishi. Previously collaborating with Miyazaki for the movies Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Castle in the Sky, Hisaishi was inspired by the contemporary composers of Terry Riley, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Stockhausen and John Cage, and also described Miyazaki’s films as «rich and personally compeling». He hired an orchestra during the film, and primarily utilised the Fairlight instrument.[8]: 169, 170

The Tonari no Totoro Soundtrack was originally released in Japan on May 1, 1988 by Tokuma Shoten, and features the musical score used in the film composed by Joe Hisaishi, except for five vocal pieces performed by Azumi Inoue, including three for the film: «Stroll», «A Lost Child», and «My Neighbor Totoro».[13] It had previously been released as an Image Song CD in 1987 that contained some songs that were not included in the film.[14]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Hey Let’s Go» | 2:43 |

| 2. | «The Village in May» | 1:38 |

| 3. | «A Haunted House» | 1:23 |

| 4. | «Mei and the Dust Bunnies» | 1:34 |

| 5. | «Evening Wind» | 1:01 |

| 6. | «Not Afraid» | 0:43 |

| 7. | «Let’s Go to the Hospital» | 1:22 |

| 8. | «Mother» | 1:06 |

| 9. | «A Little Monster» | 3:54 |

| 10. | «Totoro» | 2:49 |

| 11. | «A Huge Tree in the Tsukamori Forest» | 2:15 |

| 12. | «A Lost Child» | 3:48 |

| 13. | «The Path of the Wind» | 3:16 |

| 14. | «A Soaking Wet Monster» | 2:33 |

| 15. | «Moonlight Flight» | 2:05 |

| 16. | «Mei is Missing» | 2:32 |

| 17. | «Cat Bus» | 2:11 |

| 18. | «I’m So Glad» | 1:15 |

| 19. | «My Neighbor Totoro- Ending Song» | 4:17 |

| 20. | «Hey Let’s Go» | 2:43 |

| Total length: | 45:18 |

Release[edit]

After writing and filming Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Castle in the Sky (1986), Hayao Miyazaki began directing My Neighbor Totoro for Studio Ghibli. Miyazaki’s production paralleled his colleague Isao Takahata’s production of Grave of the Fireflies. Miyazaki’s film was financed by executive producer Yasuyoshi Tokuma, and both My Neighbor Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies were released on the same bill in 1988. The dual billing was considered «one of the most moving and remarkable double bills ever offered to a cinema audience».[16]

Box office[edit]

In Japan, My Neighbor Totoro initially sold 801,680 tickets and earned a distribution rental income of ¥588 million in 1988. According to image researcher Seiji Kano, by 2005 the film’s total box office gross receipts in Japan amounted to ¥1.17 billion[17] ($10.6 million).[18] In France, the film sold 429,822 tickets since 1999.[19] The film received further international releases since 2002.[20] The film went on to gross $30,476,708 overseas since 2002,[21] for a total of $41,076,708 at the worldwide box office.

30 years after its original release in Japan, My Neighbour Totoro received a Chinese theatrical release in December 2018. The delay was due to long-standing political tensions between China and Japan, but many Chinese nevertheless became familiar with Miyazaki’s films due to rampant video piracy.[22] In its opening weekend, ending December 16, 2018, My Neighbour Totoro grossed $13 million, entering the box office charts at number two, behind only Hollywood film Aquaman at number one and ahead of Bollywood film Padman at number three.[23] By its second weekend, My Neighbor Totoro grossed $20 million in China.[24] As of February 2019, it grossed $25,798,550 in China.[20]

English dubs[edit]

In 1988, US-based company Streamline Pictures produced an exclusive English language dub of the film for use as an in-flight movie on Japan Airlines flights. However, due to his disappointment with the result of the heavily edited 95 minute English version of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Miyazaki and Ghibli would not permit any part of the film to be edited out, all the names remained the same (with the exception being Catbus), the translation was as close to the original Japanese script as possible, and no part of the film could be changed for any reason, cultural or linguistic (which was very common at the time) despite creating problems with some English viewers, particularly in explaining the origin of the name «Totoro». It was produced by John Daly and Derek Gibson, with co-producer Jerry Beck. In April 1993, Troma Films, under their 50th St. Films banner, distributed the dub of the film as a theatrical release, and was later released onto VHS by Fox Video.

In 2004, Walt Disney Pictures produced an all new English dub of the film to be released after the rights to the Streamline dub had expired. As is the case with Disney’s other English dubs of Miyazaki films, the Disney version of Totoro features a star-heavy cast, including Dakota and Elle Fanning as Satsuki and Mei, Timothy Daly as Mr. Kusakabe, Pat Carroll as Granny, Lea Salonga as Mrs. Kusakabe, and Frank Welker as Totoro and Catbus. The songs for the new dub retain the same translation as the previous dub, but are sung by Sonya Isaacs.[25] The songs for the Streamline version of Totoro are sung by Cassie Byram.[26] The dub was directed by Rick Dempsey, a Disney executive in charge of the company’s dubbing services, and written by Don and Cindy Hewitt, who had written other dubs for Ghibli films, including Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, Porco Rosso, Whisper of the Heart, and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

Disney’s English-language dub premiered on October 23, 2005; it then appeared at the 2005 Hollywood Film Festival. The Turner Classic Movies cable television network held the television premiere of Disney’s new English dub on January 19, 2006, as part of the network’s salute to Hayao Miyazaki. (TCM aired the dub as well as the original Japanese with English subtitles.) The Disney version was initially released on DVD in the United States on March 7, 2006, but is now out of print. This version of the film has since been used in all English-speaking regions and is one of the two versions most widely available, especially for streaming on Netflix and HBO Max.

Home media[edit]

The film was released to VHS and LaserDisc by Tokuma Shoten in August 1988 under their Animage Video label. Buena Vista Home Entertainment Japan (now Walt Disney Japan) would later reissue the VHS on June 27, 1997 as part of their Ghibli ga Ippai series, and was later released to DVD on September 28, 2001, including both the original Japanese and the Streamline Pictures English dub. Disney would later release the film on Blu-ray in the country on July 18, 2012. The DVD was re-released on July 16, 2014, using the remastered print from the Blu-ray and having the Disney produced English dub instead of Streamline’s.

In 1993, Fox Video licensed the film from Studio Ghibli and released the Streamline Pictures dub of My Neighbor Totoro on VHS and LaserDisc in the United States and was later released to DVD in 2002. After the rights to the dub expired in 2004, Walt Disney Home Entertainment re-released the movie on DVD on March 7, 2006 with Disney’s newly produced English dub and the original Japanese version. A reissue of Totoro, Castle in the Sky, and Kiki’s Delivery Service featuring updated cover art highlighting its Studio Ghibli origins was released by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment on March 2, 2010, coinciding with the US DVD and Blu-ray debut of Ponyo, and was subsequently released by Disney on Blu-Ray Disc on May 21, 2013. GKIDS re-issued the film on Blu-ray and DVD on October 17, 2017.[27]

The Disney-produced dub has also been released onto DVD and Blu-ray by distributors like Madman Entertainment in Australia and Optimum Releasing/StudioCanal UK in the United Kingdom.

In Japan, the film sold 3.5 million VHS and DVD units as of April 2012,[28] equivalent to approximately ¥16,100 million ($202 million) at an average retail price of ¥4,600 (¥4,700 on DVD and ¥4,500 on VHS).[29] In the United States, the film sold over 500,000 VHS units by 1996,[30] equivalent to approximately $10 million at a retail price of $19.98,[31] with the later 2010 DVD release selling a further 3.8 million units and grossing $64.5 million in the United States as of October 2018.[32] In total, the film’s home video releases have sold 7.8 million units and grossed an estimated $277 million in Japan and the United States.

In the United Kingdom, the film’s Studio Ghibli anniversary release appeared on the annual lists of top ten best-selling foreign language films on home video for five consecutive years, ranking number seven in 2015,[33] number six in 2016[34] and 2017,[35] number one in 2018,[36] and number two in 2019 (below Spirited Away).[37]

Reception[edit]

My Neighbor Totoro received widespread acclaim from film critics.[38][39] Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reported that 95% of critics gave positive reviews, with an average rating of 8.5/10 based on 55 reviews. The website’s critical consensus states, “My Neighbor Totoro is a heartwarming, sentimental masterpiece that captures the simple grace of childhood.»[40] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average rating of 86 out of 100, based on 15 critics, indicating «universal acclaim». It is listed as a «must-see» by Metacritic.[41] In 2001, the Japanese magazine Animage ranked My Neighbor Totoro 45th in their list of 100 Best Anime Productions of All Time.[42] My Neighbor Totoro was voted the highest-ranking animated film on the 2012 Sight & Sound critics’ poll of all-time greatest films, and joint 154th overall.[3] In 2022, the film was ranked by the magazine as the joint 72nd greatest film overall, being one of the two animated films included in the list along with Spirited Away.[43][44] In addition, the film was ranked at number 3 on the list of the Greatest Japanese Animated Films of All Time by film magazine Kinema Junpo in 2009, 41st in Empire magazine’s «The 100 Best Films of World Cinema» in 2010, number two for a similar Empire list for best children’s films, and number 1 in the greatest animated films in Time Out ranked the film number 1, a similar list by the editors ranked the film number 3 instead.[4][45][46][47]

Film critic Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times identified My Neighbor Totoro as one of his «Great Movies», calling it «one of the lovingly hand-crafted works of Hayao Miyazaki». In his review, Ebert observed that «My Neighbor Totoro is based on experience, situation and exploration—not on conflict and threat», and described its appeal as «it would never have won its worldwide audience just because of its warm heart. It is also rich with human comedy in the way it observes the two remarkably convincing, lifelike little girls…. It is a little sad, a little scary, a little surprising and a little informative, just like life itself. It depends on a situation instead of a plot, and suggests that the wonder of life and the resources of imagination supply all the adventure you need».[48] Steve Rose from The Guardian rated the film five stars, praising Miyazaki’s «rich, bright, hand-drawn» animation and describing it as «full of benign spirituality, prelapsarian innocence and joyous discovery, all rooted in a carefully detailed reality».[49] Trevor Johnston from Time Out also awarded the film five stars commenting on the film’s «delicate rendering of the atmosphere» and its first half that «delicately captures both mystery and quietness».[50] The Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa also cited My Neighbor Totoro as one of his favorite films.[51][52] Writing for the London Evening Standard, Charlotte O’Sullivan praised the charm of the film, but said that its complexity was lacking compared to Spirited Away.[53] Jordan Cronk from Slant awarded the film three and half stars but also suggested was «devoid of much of the fantasia of Miyazaki’s more outwardly visionary work».[54]

The 1993 translation was not as well received as the 2006 translation, with Leonard Klady of the entertainment trade newspaper Variety wrote of the 1993 translation, that My Neighbor Totoro demonstrated «adequate television technical craft» that was characterized by «muted pastels, homogenized pictorial style and [a] vapid storyline». The film’s environment was described as «Obviously aimed at an international audience» but «evinces a disorienting combination of cultures that produces a nowhere land more confused than fascinating.»[55] Stephen Holden of The New York Times described the 1993 translation as «very visually handsome», and believed that the film was «very charming» when «dispensing enchantment». Despite the highlights, Holden wrote, «Too much of the film, however, is taken up with stiff, mechanical chitchat.»[56]

Matthew Leyland of Sight & Sound reviewed the DVD released in 2006, commenting that «Miyazaki’s family fable is remarkably light on tension, conflict and plot twists, yet it beguiles from beginning to end… what sticks with the viewer is the every-kid credibility of the girls’ actions as they work, play and settle into their new surroundings.» Leyland praised the DVD transfer of the film, but noted that the disc lacked a look at the film’s production, instead being overabundant with storyboards.[57]

Writing in Joe Hisaishi’s Soundtrack for My Neighbor Totoro, Kunio Hara also praised the soundtrack, describing the song «My Neighbor Totoro» as a «sonic icon» of the film. Hara additionally commented that the music «arouse a similar sentiment of yearning for the past».[58]

Awards and nominations[edit]

| Year | Title | Award | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | My Neighbor Totoro | Kinema Junpo Awards | Kinema Junpo Award – Best Film | Won |

| Readers’ Choice Award – Best Japanese Film | Won | |||

| Mainichi Film Award | Best Film | Won | ||

| Ōfuji Noburō Award | Won | |||

| Blue Ribbon Awards | Special Award | Won | ||

| Animage Anime Awards | Grand Prix prize | Won | ||

| 1995 | Saturn Awards | Best Genre Video Release | Nominated |

Legacy[edit]

My Neighbor Totoro was considered as a milestone for writer-director Hayao Miyazaki. The film’s central character, Totoro, is as famous among Japanese children as Winnie-the-Pooh is among British ones.[59] The Independent recognized Totoro as one of the greatest cartoon characters, describing the creature, «At once innocent and awe-inspiring, King Totoro captures the innocence and magic of childhood more than any of Miyazaki’s other magical creations.»[60] The Financial Times recognized the character’s appeal, commenting that Totoro «is more genuinely loved than Mickey Mouse could hope to be in his wildest—not nearly so beautifully illustrated—fantasies.»[59] Similarly, Empire also commented on Totoro’s appeal, ranking it 18th for best animated characters.[61] Totoro and characters from the movie play a significant role in the Ghibli Museum, including a large catbus and the Straw Hat Cafe.[62]

The environmental journal Ambio described the influence of My Neighbor Totoro, «[It] has served as a powerful force to focus the positive feelings that the Japanese people have for satoyama and traditional village life.» The film’s central character Totoro was used as a mascot by the Japanese «Totoro Hometown Fund Campaign» to preserve areas of satoyama in the Saitama Prefecture.[63] The fund, started in 1990 after the film’s release, held an auction in August 2008 at Pixar Animation Studios to sell over 210 original paintings, illustrations, and sculptures inspired by My Neighbor Totoro.[64]

Totoro has made cameo appearances in many Studio Ghibli films, including Pom Poko, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Whisper of the Heart. Various other anime series and films have featured cameos, including one episode of the Gainax TV series His and Her Circumstances. Miyazaki uses Totoro as a part of his Studio Ghibli company logo.[1]

A main-belt asteroid, discovered on December 31, 1994, was named 10160 Totoro after the film’s central character.[65] Totoro makes a cameo appearance in the Pixar film Toy Story 3 (2010)[66] but did not make a appearance in Toy Story 4 due to licensing;[67] the film’s art director Daisuke Tsutsumi is married to Miyazaki’s niece, who was the original inspiration for the character Mei in My Neighbour Totoro.[9]

In 2013, a velvet worm species Eoperipatus totoro discovered in Vietnam was named after Totoro: «Following the request of Pavel V. Kvartalnov, Eduard A. Galoyan and Igor V. Palko, the species is named after the main character of the cartoon movie «My Neighbour Totoro» by Hayao Miyazaki (1988, Studio Ghibli), who uses a many-legged animal as a vehicle, which according to the collectors resembles a velvet worm.»[68]

Media[edit]

Books[edit]

A four-volume series of ani-manga books, which use color images and lines directly from the film, was published in Japan in May 1988 by Tokuma.[69][70] The series was licensed for English language release in North America by Viz Media, which released the books from November 10, 2004, through February 15, 2005.[71][72][73][74] A 111-page picture book based on the film and aimed at younger readers was released by Tokuma on June 28, 1988 and, in a 112-page English translation, by Viz on November 8, 2005.[75][76] Tokuma later released an additional 176-page art book containing conceptual art from the film and interviews with the production staff on July 15, 1988 and, in English translation, by Viz on November 8, 2005.[77][78] In 2013, a hardcover light novel written by Tsugiko Kubo and illustrated by Hayao Miyazaki was released by Viz.[79]

Anime short[edit]

Mei and the Kittenbus (めいとこねこバス, Mei to Konekobasu) is a thirteen-minute sequel to My Neighbor Totoro, written and directed by Miyazaki.[80] Chika Sakamoto, who voiced Mei in Totoro, returned to voice Mei in this short. Hayao Miyazaki himself did the voice of the Granny Cat (Neko Baa-chan), as well as Totoro. It concentrates on the character of Mei Kusakabe from the original film and her adventures one night with the Kittenbus (the offspring of the Catbus from the film) and other cat-oriented vehicles.

Originally released in Japan in 2003, the short is regularly shown at the Ghibli Museum,[81] but has not been released to home video. It was shown briefly in the United States in 2006 to honor the North American release of fellow Miyazaki film Spirited Away[82] and at a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation fundraiser a few days later.[83]

Merchandise[edit]

Numerous licensed merchandise of Totoro have been sold in Japan for decades after the film’s release. Totoro licensed merchandise sales in Japan grossed ¥10.97 billion in 1999, ¥56.08 billion during 2003–2007,[84] at least ¥4.1 billion in 2008,[85] and ¥19.96 billion during 2010–2012.[84] Combined, the Totoro licensed merchandise sales have grossed at least ¥91.11 billion ($1,142 million) in Japan between 1999 and 2012.

Stage adaptation[edit]

In May 2022, the Royal Shakespeare Company and composer Joe Hisaishi announced a stage adaptation of My Neighbour Totoro set to run from 8 October 2022 to 21 January 2023 at the Barbican Centre in London.[86] It will be adapted by British playwright Tom Morton-Smith and directed by Improbable’s Phelim McDermott.[87] Tickets went on sale on 19 May 2022 breaking the theatre’s box office record for sales in one day (previously held by the 2015 production of Hamlet starring Benedict Cumberbatch).[88]

See also[edit]

- Japan, Our Homeland and Mai Mai Miracle (also depicting Japan in the 1950s)

- Enchanted forest

Notes[edit]

- ^ Called «black soots» in early subtitles and «soot sprites» in the later English dubbed version.

References[edit]

- ^ a b «My Neighbor Totoro». TIFF. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro — Studio Ghibli Collection». Studio Ghibli — Limited Edition ORDER NOW from your favourite retailer. Archived from the original on August 30, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ a b «The greatest animated films of all time?». British Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ a b «The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema – 41. My Neighbor Totoro». Empire. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Tonari no Totoro — FAQ.

- ^ a b c Ogihara-Schuck, Eriko (2014). Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad: The Reception of Japanese Religious Themes by American and German Audiences. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 81–83. ISBN 978-1-4766-1395-6.

- ^ Phillip E. Wegner (March 14, 2010). «An Unfinished Project that was Also a Missed Opportunity: Utopia and Alternate History in Hayao Miyazakis My Neighbor Totoro». English.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Watsuki, Nobuhiro (2005). The Art of My Neighbor Totoro: A Film by Hayao Miyazaki. VIZ Media LLC. ISBN 978-1591166986.

- ^ a b «Toy Story 3 Art Director Married to Hayao Miyazaki’s Niece – Interest». Anime News Network. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Kikuchi, Yoshiaki (August 4, 2007). «Totoro’s set decorator». Daily Yomiuri.

- ^ a b «When Studio Ghibli is mentioned, usually the name of its co-founder and chief director Hayao Miyazaki springs to mind. But anyone with an awareness of the labor-intensive animation process knows that such masterpieces as Tonari no Totoro…». International Herald Tribune-Asahi Shimbun. August 24, 2007.

- ^ «Studio Ghibli co-founder teases Hayao Miyazaki’s next ‘big, fantastical’ film». Entertainment Weekly. May 15, 2020. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ «Tonari no Totoro (My Neighbor Totoro) Soundtracks». CD Japan. Neowing. Archived from the original on January 3, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ Joe Hisaishi’s Soundtrack for My Neighbor Totoro. Bloomsbury. February 6, 2020. ISBN 9781501345128. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ My Neighbor Totoro (Original Soundtrack) by Joe Hisaishi, May 1, 1988, archived from the original on March 4, 2022, retrieved March 4, 2022

- ^ McCarthy, Helen (1999). Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation. Stone Bridge Press. pp. 43, 120–121. ISBN 978-1-880656-41-9.

- ^ Kanō, Seiji [in Japanese] (March 1, 2006). 宮崎駿全書 (Complete Miyazaki Hayao) (Shohan ed.). フィルムアート社 (Film Art Company). p. 124. ISBN 978-4845906871.

- ^ «Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average) — Japan». World Bank. 2005. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ «Tonari no Totoro (1999)». JP’s Box Office (in French). Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ a b «Tonari no Totoro (My Neighbor Totoro) (2002)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ «These five Studio Ghibli films really should be released in China». South China Morning Post. December 17, 2018. Archived from the original on June 25, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- ^ «China’s No. 2 Film This Weekend Was Hayao Miyazaki’s ‘My Neighbor Totoro’«. Variety. December 17, 2018. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Davis, Becky (December 24, 2018). «China Box Office: ‘Spider-Verse’ Shoots to Opening Weekend Victory». Variety. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ My Neighbor Totoro, archived from the original on February 6, 2018, retrieved February 4, 2018

- ^ From ‘Mere’ to ‘Interesting’ [Cassie’s Corner], archived from the original on June 22, 2018, retrieved June 4, 2018

- ^ Carolyn Giardina (July 17, 2017). «Gkids, Studio Ghibli Ink Home Entertainment Deal». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 22, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ «「となりのトトロ」ついにブルーレイ発売». MSN エンタメ. MSN. May 2, 2012. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro: Video List». Nausicaa.net. Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ Furniss, Maureen (2009). Animation: Art and Industry. Indiana University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780861969043. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ «Suppliers Aim Kid Vids At Parents». Billboard. Vol. 106, no. 26. Nielsen Business Media. June 25, 1994. p. 60. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ «Tonari no Totoro (1996) — Video Sales». The Numbers. Archived from the original on December 17, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook 2016 (PDF). United Kingdom: British Film Institute (BFI). 2016. p. 144. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook 2017 (PDF). United Kingdom: British Film Institute (BFI). 2017. pp. 140–1. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook 2018 (PDF). United Kingdom: British Film Institute (BFI). 2018. pp. 97–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook 2019 (PDF). United Kingdom: British Film Institute (BFI). 2019. pp. 103–4. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ BFI Statistical Yearbook 2020. United Kingdom: British Film Institute (BFI). 2020. p. 94. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Zipes, Jack; Greenhill, Pauline; Magnus-Johnston, Kendra (September 16, 2015). Fairy-Tale Films Beyond Disney: International Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-62820-9.

- ^ Merskin, Debra L. (November 12, 2019). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4833-7554-0.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro (1988)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro Reviews». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ «Animage Top-100 Anime Listing». Anime News Network. January 15, 2001. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ «The Greatest Films of All Time». BFI. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Ugwu, Reggie (December 1, 2022). «Chantal Akerman’s ‘Jeanne Dielman’ Named Greatest Film of All Time in Sight and Sound Poll». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ Time Out’s 50 greatest animated films, with added commentary by Terry Gilliam. Archived from the original October 9, 2009

- ^ «Kinema Junpo Top 10 Animated Films». Nishikata Film Review. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ «The 50 best kids’ movies». Empire. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 23, 2001). «My Neighbor Totoro (1993)». Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ «My Neighbour Totoro – review». the Guardian. May 23, 2013. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Johnston, Trevor. «My Neighbour Totoro». Time Out Worldwide. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Lee Thomas-Mason (January 12, 2021). «From Stanley Kubrick to Martin Scorsese: Akira Kurosawa once named his top 100 favourite films of all time». Far Out. Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ «Akira Kurosawa’s Top 100 Movies!». Archived from the original on 27 March 2010.

- ^ «My Neighbour Totoro — film review». www.standard.co.uk. May 24, 2013. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Cronk, Jordan (May 31, 2013). «Review: Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro on Disney Blu-ray». Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (May 6, 1993). «My Neighbor Totoro». Variety. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (June 14, 1993). «Review/Film; Even a Beast Is Sweet as Can Be». The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017.

- ^ Leyland, Matthew (June 2006). «My Neighbour Totoro». Sight & Sound. 16 (6): 89.

- ^ Hara, Kunio (February 6, 2020). Joe Hisaishi’s Soundtrack for My Neighbor Totoro. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-5013-4513-5.

- ^ a b Pilling, David (September 15, 2007). «Defining Moment: My Neighbour Totoro, 1988, directed by Hayao Miyazaki». Financial Times.

- ^ Forbes, Dee (November 7, 2005). «Analysis Cartoons: Toontown’s greatest characters». The Independent.

- ^ «The Best Animated Film Characters — 18. Totoro». Empire. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- ^ Takai, Shinichi. «Welcome! — Ghibli Museum, Mitaka». www.ghibli-museum.jp. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Kobori, Hiromi; Richard B. Primack (June 2003). «Participatory Conservation Approaches for Satoyama, the Traditional Forest and Agricultural Landscape of Japan». Ambio. 32 (4): 307–311. doi:10.1639/0044-7447(2003)032[0307:pcafst]2.0.co;2. PMID 12956598.

- ^ Giardina, Carolyn (August 27, 2008). «‘Neighbor’ inspires artists». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 30, 2008.[permanent dead link][permanent dead link]

- ^ «10160 Totoro (1994 YQ1)». Solar System Dynamics. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ Campbell, Christopher (February 17, 2010). «Pixar Chief Discusses Totoro Cameo In ‘Toy Story 3’ Trailer». MTV News. MTV. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ Moviefone, Staff (May 1, 2019). «‘Toy Story 4’ Director and Producers on Tinny, Totoro and How Time Works in the Franchise». moviefone. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ I D S Oliveira, S Schaffer, P V Kvartalnov , E A Galoyan, I V Palko, A Weck-Heimann, P Geissler, H Ruhberg (2013). «A new species of Eoperipatus (Onychophora) from Vietnam reveals novel morphological characters for the South-East Asian Peripatidae». Zoologischer Anzeiger — A Journal of Comparative Zoology. 252 (4): 495–510. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2013.01.001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Miyazaki, Hayao (May 28, 1988). フィルムコミック となりのトトロ (1) [Film Comic My Neighbour Totoro (1)] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten. ISBN 978-4-19-778561-2. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ Miyazaki, Hayao (May 28, 1988). フィルムコミック となりのトトロ (4) [Film Comic My Neighbour Totoro (4)] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten. ISBN 978-4-19-778564-3. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro Film Comic, Vol. 1». Viz Media. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro Film Comic, Vol. 2». Viz Media. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro Film Comic, Vol. 3». Viz Media. Archived from the original on April 19, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro Film Comic, Vol. 4». Viz Media. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Miyazaki, Hayao (June 28, 1988). 徳間アニメ絵本4 となりのトトロ [Tokuma Anime Picture Book 4 My Neighbour Totoro] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten. ISBN 978-4-19-703684-4. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ «My Neighbor Totoro Picture Book». Viz Media. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Miyazaki, Hayao (July 15, 1988). ジアート となりのトトロ [The Art of My Neighbour Totoro] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten. ISBN 978-4-19-818580-0. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ «The Art of My Neighbor Totoro». Viz Media. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Miyazaki, Hayao; Kubo, Tsugiko (October 1, 2013). My Neighbor Totoro: The Novel. Illustrated by Hayao Miyazaki. Viz Media, Imprint: Studio Ghibli Library. ISBN 9781421561202. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017.

- ^ «Miyazaki Plans Museum Anime Shorts After Ponyo». Anime News Network. June 20, 2008. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ «三鷹の森 ジブリ美術館 – 映像展示室 土星座». Archived from the original on February 28, 2008. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ^ «Synopsis – Page 1». Lasseter-San, Arigato (Thank You, Mr. Lasseter). Nausicaa.Net. Archived from the original on December 14, 2005. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ «Synopsis – Page 6». Lasseter-San, Arigato (Thank You, Mr. Lasseter). Nausicaa.Net. Archived from the original on June 8, 2005. Retrieved May 23, 2006.

- ^ a b «在日本,地位最高的动漫是哆啦a梦么?». Taojinjubao. Character Databank (CharaBiz). January 6, 2018. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- ^ CharaBiz DATA 2009⑧ (in Japanese). Character Databank, Ltd. 2009. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- ^ «‘My Neighbor Totoro’ gets London stage play adaptation produced by Ghibli composer Joe Hisaishi». news.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ «RSC to adapt My Neighbour Totoro for London stage premiere this autumn | WhatsOnStage». www.whatsonstage.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Wild, Stephi. «World Premiere of MY NEIGHBOUR TOTORO Stage Adaptation Breaks Barbican Box Office Record». BroadwayWorld.com. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

External links[edit]

- Official U.S. website

- My Neighbor Totoro (film) at Anime News Network’s encyclopedia

- My Neighbor Totoro at IMDb

- My Neighbor Totoro at Rotten Tomatoes

- Mei and the Kitten Bus (2002) at IMDb

- Entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

- Joe Hisaishi’s Soundtrack for My Neighbor Totoro, book by Kunio Hara, 33-1/3 Japan Series, Bloomsbury, ISBN 9781501345128

| My Neighbor Totoro | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Japanese theatrical release poster |

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | となりのトトロ | ||

|

|||

| Directed by | Hayao Miyazaki | ||

| Written by | Hayao Miyazaki | ||

| Produced by | Toru Hara | ||

| Starring |

|

||

| Cinematography | Hisao Shirai | ||

| Edited by | Takeshi Seyama | ||

| Music by | Joe Hisaishi | ||

|

Production |

Studio Ghibli |

||

| Distributed by | Toho | ||

|

Release date |

|

||

|

Running time |

86 minutes | ||

| Country | Japan | ||

| Language | Japanese | ||

| Box office | $41 million |

My Neighbor Totoro (Japanese: となりのトトロ, Hepburn: Tonari no Totoro, lit. ‘Neighbour of Totoro’) is a 1988 Japanese animated fantasy film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki and animated by Studio Ghibli for Tokuma Shoten. The film—which stars the voice actors Noriko Hidaka, Chika Sakamoto, and Hitoshi Takagi—tells the story of a professor’s two young daughters (Satsuki and Mei) and their interactions with friendly wood spirits in postwar rural Japan.

In 1989, Streamline Pictures produced an English-language dub for exclusive use on transpacific flights by Japan Airlines. Troma Films, under their 50th St. Films banner, distributed the dub of the film co-produced by Jerry Beck. This dub was released to United States theaters in 1993, on VHS and LaserDisc in the United States by Fox Video in 1994, and on DVD in 2002. The rights to this dub expired in 2004, so the film was re-released by Walt Disney Home Entertainment on March 7, 2006[1] with a new dub cast. This version was also released in Australia by Madman on March 15, 2006[2] and in the UK by Optimum Releasing on March 27, 2006. This DVD release is the first version of the film in the United States to include both Japanese and English language tracks.

Exploring themes such as animism, Shinto symbology, environmentalism and the joys of rural living, My Neighbor Totoro received worldwide critical acclaim and has amassed a global cult following in the years after its release. The film has grossed over $41 million at the worldwide box office as of September 2019, in addition to generating an estimated $277 million from home video sales and $1.142 billion from licensed merchandise sales, adding up to approximately $1.46 billion in total lifetime revenue.

My Neighbor Totoro received numerous awards, including the Animage Anime Grand Prix prize, the Mainichi Film Award and Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film in 1988. It also received the Special Award at the Blue Ribbon Awards in the same year. The film is considered as one of the top animation films, ranking 41st in Empire magazine’s «The 100 Best Films of World Cinema» in 2010 and being the highest-ranking animated film on the 2012 Sight & Sound critics’ poll of all-time greatest films.[3][4] The film and its titular character have become cultural icons and made multiple cameo appearances in a number of Studio Ghibli films and video games. Totoro also serves as the mascot for the studio and is recognized as one of the most popular characters in Japanese animation.

Plot[edit]

In 1950s Japan, university professor Tatsuo Kusakabe and his two daughters, Satsuki and Mei (approximately ten and four years old, respectively), move into an old house closer to the hospital where the girls’ mother, Yasuko, is recovering from a long-term illness. The house is inhabited by small, dark, dust-like house spirits called susuwatari, which can be seen when moving from bright to dark places.[note 1] When the girls become comfortable in their new house, the susuwatari leave to find another empty house. One day, Mei discovers two small spirits who lead her into the hollow of a large camphor tree. She befriends a larger spirit, which identifies itself by a series of roars that she interprets as «Totoro». Mei thinks Totoro is the Troll from her illustrated book Three Billy Goats Gruff, with her mispronouncing Troll. She falls asleep atop Totoro, but when Satsuki finds her, she is on the ground. Despite many attempts, Mei cannot show her family Totoro’s tree. Tatsuo comforts her by telling her that Totoro will reveal himself when he wants to.

Closeup view of Satsuki and Mei’s house

One rainy night, the girls are waiting for Tatsuo’s bus, which is late. Mei falls asleep on Satsuki’s back, and Totoro appears beside them, allowing Satsuki to see him for the first time. Totoro has only a leaf on his head for protection against the rain, so Satsuki offers him the umbrella she had taken for her father. Delighted, he gives her a bundle of nuts and seeds in return. A giant, bus-shaped cat halts at the stop, and Totoro boards it and leaves. Shortly after, Tatsuo’s bus arrives. A few days after planting the seeds, the girls awaken at midnight to find Totoro and his colleagues engaged in a ceremonial dance around the planted seeds and join in, causing the seeds to grow into an enormous tree. Totoro takes the girls for a ride on a magical flying top. In the morning, the tree is gone, but the seeds have sprouted.

The girls discover that a planned visit by Yasuko has to be postponed because of a setback in her treatment. Mei does not take this well and argues with Satsuki, leaving for the hospital to bring fresh corn to Yasuko. Her disappearance prompts Satsuki and the neighbors to search for her. In desperation, Satsuki returns to the camphor tree and pleads for Totoro’s help. He delightfully summons the Catbus, which carries her to where the lost Mei sits, and the sisters emotionally reunite. The bus then takes them to the hospital. The girls overhear a conversation between their parents and learn that she has been kept in hospital by a minor cold but is otherwise doing well. They secretly leave the ear of corn on the windowsill, where their parents discover it, and return home. Eventually, Yasuko returns home, and the sisters play with other children while Totoro and his friends watch them from afar.

Characters[edit]

The name Totoro comes from a misprononciation of the word troll (トロール, torōru) by Mei. She has seen one in a book and decides that it must be the same creature.[5]

The cat-bus comes from a Japanese belief attributing to an old cat the power of shape-shifting: he then becomes a «bakeneko». The cat-bus is a «bakeneko» who has seen a bus and decided to become one.[5]

Themes[edit]

Animism is a large theme in this film according to Eriko Ogihara-Schuck.[6] Totoro has animistic traits and has kami status due to the fact that he lives in a camphor tree in a Shinto shrine surrounded by a Shinto rope and was referred to as «mori no nushi,» or «master of the forest».[6] Moreover, Ogihara-Schuck writes that when Mei returns from her encounter with Totoro her father takes Mei and her sister to the shrine to greet and thank Totoro. This is a common practice in the Shinto tradition following an encounter with a kami.[6] The themes of the film was additionally noted for Phillip E. Wegner, who believed the film as being an example of alternative history citing the utopian-like setting of the anime.[7]

Voice cast[edit]

| Character name | Japanese voice actor | English voice actor (Tokuma/Streamline/50th Street Films, 1989/1993) |

English voice actor (Walt Disney Home Entertainment, 2005) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satsuki Kusakabe (草壁 サツキ) (10-year-old daughter) | Noriko Hidaka | Lisa Michelson | Dakota Fanning |

| Mei Kusakabe (草壁 メイ) (4-year-old daughter) | Chika Sakamoto | Cheryl Chase | Elle Fanning |

| Tatsuo Kusakabe (草壁 タツオ) (father) | Shigesato Itoi | Greg Snegoff | Tim Daly |

| Yasuko Kusakabe (草壁 靖子) (mother) | Sumi Shimamoto | Alexandra Kenworthy | Lea Salonga |

| Totoro (トトロ) | Hitoshi Takagi | — | Frank Welker |

| Kanta Ōgaki (大垣 勘太) (a local boy) | Toshiyuki Amagasa | Kenneth Hartman | Paul Butcher |

| Granny (祖母) (Nanny in the 1993 dub) | Tanie Kitabayashi | Natalie Core | Pat Carroll |

| Catbus (ネコバス, Nekobasu) | Naoki Tatsuta | Carl Macek (uncredited) | Frank Welker |

| Michiko (ミチ子) | Chie Kōjiro | Brianne Siddall (uncredited) | Ashley Rose Orr |

| Mrs. Ogaki (Kanta’s mother) | Hiroko Maruyama | Melanie MacQueen | Kath Soucie |

| Mr. Ogaki (Kanta’s father) | Masashi Hirose | Steve Kramer | David Midthunder |

| Old Farmer | — | Peter Renaday | |

| Miss Hara (Satsuki’s teacher) | Machiko Washio | Edie Mirman (uncredited) | Tress MacNeille (uncredited) |

| Kanta’s Aunt | Reiko Suzuki | Russi Taylor | |

| Otoko | Daiki Nakamura | Kerrigan Mahan (uncredited) | Matt Adler |

| Ryōko | Yūko Mizutani | Lara Cody | Bridget Hoffman |

| Bus Attendant | — | Kath Soucie | |

| Mailman | Tomomichi Nishimura | Doug Stone (uncredited) | Robert Clotworthy |

| Moving Man | Shigeru Chiba | Greg Snegoff | Newell Alexander |

Production[edit]

We need a new method and sense of discovery to be up to the task. Rather than be sentimental, the film must be a joyful, entertaining film.

—Hayao Miyazaki[8]

Development[edit]

After working on 3000 Miles in Search of A Mother, Miyazaki conceptualised making a «delightful, wonderful film» that would be set in Japan with the idea to «entertain and touch its viewers, but stay with them long after they have left the theaters». Initially, Miyazaki had the main characters of Totoros, Mei, Tatsuo, Kanta.[8]: 8 The director conceptualised Mei on his niece,[9] and the Totoros as «serene, carefree creatures» that were «supposedly the forest keeper, but that’s only a half-baked idea, a rough approximation».[8]: 5, 103

Art director Kazuo Oga was drawn to the film when Hayao Miyazaki showed him an original image of Totoro standing in a satoyama. The director challenged Oga to raise his standards, and Oga’s experience with My Neighbor Totoro jump-started the artist’s career. Oga and Miyazaki debated the palette of the film, Oga seeking to paint black soil from Akita Prefecture and Miyazaki preferring the color of red soil from the Kantō region.[8]: 82 The ultimate product was described by Studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki: «It was nature painted with translucent colors.»[10]

Oga’s conscientious approach to My Neighbor Totoro was a style that the International Herald Tribune recognized as «[updating] the traditional Japanese animist sense of a natural world that is fully, spiritually alive». The newspaper described the final product:

Set in a period that is both modern and nostalgic, the film creates a fantastic, yet strangely believable universe of supernatural creatures coexisting with modernity. A great part of this sense comes from Oga’s evocative backgrounds, which give each tree, hedge and twist in the road an indefinable feeling of warmth that seems ready to spring into sentient life.[11]

Oga’s work on My Neighbor Totoro led to his continued involvement with Studio Ghibli. The studio assigned jobs to Oga that would play to his strengths, and Oga’s style became a trademark style of Studio Ghibli.[11]

In several of Miyazaki’s initial conceptual watercolors, as well as on the theatrical release poster and on later home video releases, only one young girl is depicted, rather than two sisters. According to Miyazaki, «If she was a little girl who plays around in the yard, she wouldn’t be meeting her father at a bus stop, so we had to come up with two girls instead. And that was difficult».[8]: 11 The opening sequence of the film was not storyboarded, Miyazaki said. «The sequence was determined through permutations and combinations determined by the time sheets. Each element was made individually and combined in the time sheets…»[8]: 27 The ending sequence depicts the mother’s return home and the signs of her return to good health by playing with Satsuki and Mei outside.[8]: 149

The storyboard depicts the town of Matsuko as the setting, with the year being 1955; Miyazaki stated that it was not exact and the team worked on a setting «in the recent past».[8]: 33 The film was originally set to be an hour long, but throughout the process it grew to respond to the social context including the reason for the move and the father’s occupation.[8]: 54 Eight animators worked on the film, which was completed in eight months.[12]

Tetsuya Endo noted numerous animation techniques that were utilised in the film. For example, the ripples were designed with «two colors of high-lighting and shading» and the rain for My Neighbor Totoro was «scratched in the cels» and superimposed for it to convey a softer feel.[8]: 156 The animators stated that one month was taken to create the tadpoles, which included four colours, the water for it was also blurred.[8]: 154

Music[edit]

The music for the film was composed by Joe Hisaishi. Previously collaborating with Miyazaki for the movies Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Castle in the Sky, Hisaishi was inspired by the contemporary composers of Terry Riley, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Stockhausen and John Cage, and also described Miyazaki’s films as «rich and personally compeling». He hired an orchestra during the film, and primarily utilised the Fairlight instrument.[8]: 169, 170

The Tonari no Totoro Soundtrack was originally released in Japan on May 1, 1988 by Tokuma Shoten, and features the musical score used in the film composed by Joe Hisaishi, except for five vocal pieces performed by Azumi Inoue, including three for the film: «Stroll», «A Lost Child», and «My Neighbor Totoro».[13] It had previously been released as an Image Song CD in 1987 that contained some songs that were not included in the film.[14]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Hey Let’s Go» | 2:43 |

| 2. | «The Village in May» | 1:38 |

| 3. | «A Haunted House» | 1:23 |

| 4. | «Mei and the Dust Bunnies» | 1:34 |

| 5. | «Evening Wind» | 1:01 |

| 6. | «Not Afraid» | 0:43 |

| 7. | «Let’s Go to the Hospital» | 1:22 |

| 8. | «Mother» | 1:06 |

| 9. | «A Little Monster» | 3:54 |

| 10. | «Totoro» | 2:49 |

| 11. | «A Huge Tree in the Tsukamori Forest» | 2:15 |

| 12. | «A Lost Child» | 3:48 |

| 13. | «The Path of the Wind» | 3:16 |

| 14. | «A Soaking Wet Monster» | 2:33 |

| 15. | «Moonlight Flight» | 2:05 |

| 16. | «Mei is Missing» | 2:32 |

| 17. | «Cat Bus» | 2:11 |

| 18. | «I’m So Glad» | 1:15 |

| 19. | «My Neighbor Totoro- Ending Song» | 4:17 |

| 20. | «Hey Let’s Go» | 2:43 |

| Total length: | 45:18 |

Release[edit]

After writing and filming Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Castle in the Sky (1986), Hayao Miyazaki began directing My Neighbor Totoro for Studio Ghibli. Miyazaki’s production paralleled his colleague Isao Takahata’s production of Grave of the Fireflies. Miyazaki’s film was financed by executive producer Yasuyoshi Tokuma, and both My Neighbor Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies were released on the same bill in 1988. The dual billing was considered «one of the most moving and remarkable double bills ever offered to a cinema audience».[16]

Box office[edit]

In Japan, My Neighbor Totoro initially sold 801,680 tickets and earned a distribution rental income of ¥588 million in 1988. According to image researcher Seiji Kano, by 2005 the film’s total box office gross receipts in Japan amounted to ¥1.17 billion[17] ($10.6 million).[18] In France, the film sold 429,822 tickets since 1999.[19] The film received further international releases since 2002.[20] The film went on to gross $30,476,708 overseas since 2002,[21] for a total of $41,076,708 at the worldwide box office.

30 years after its original release in Japan, My Neighbour Totoro received a Chinese theatrical release in December 2018. The delay was due to long-standing political tensions between China and Japan, but many Chinese nevertheless became familiar with Miyazaki’s films due to rampant video piracy.[22] In its opening weekend, ending December 16, 2018, My Neighbour Totoro grossed $13 million, entering the box office charts at number two, behind only Hollywood film Aquaman at number one and ahead of Bollywood film Padman at number three.[23] By its second weekend, My Neighbor Totoro grossed $20 million in China.[24] As of February 2019, it grossed $25,798,550 in China.[20]

English dubs[edit]

In 1988, US-based company Streamline Pictures produced an exclusive English language dub of the film for use as an in-flight movie on Japan Airlines flights. However, due to his disappointment with the result of the heavily edited 95 minute English version of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Miyazaki and Ghibli would not permit any part of the film to be edited out, all the names remained the same (with the exception being Catbus), the translation was as close to the original Japanese script as possible, and no part of the film could be changed for any reason, cultural or linguistic (which was very common at the time) despite creating problems with some English viewers, particularly in explaining the origin of the name «Totoro». It was produced by John Daly and Derek Gibson, with co-producer Jerry Beck. In April 1993, Troma Films, under their 50th St. Films banner, distributed the dub of the film as a theatrical release, and was later released onto VHS by Fox Video.

In 2004, Walt Disney Pictures produced an all new English dub of the film to be released after the rights to the Streamline dub had expired. As is the case with Disney’s other English dubs of Miyazaki films, the Disney version of Totoro features a star-heavy cast, including Dakota and Elle Fanning as Satsuki and Mei, Timothy Daly as Mr. Kusakabe, Pat Carroll as Granny, Lea Salonga as Mrs. Kusakabe, and Frank Welker as Totoro and Catbus. The songs for the new dub retain the same translation as the previous dub, but are sung by Sonya Isaacs.[25] The songs for the Streamline version of Totoro are sung by Cassie Byram.[26] The dub was directed by Rick Dempsey, a Disney executive in charge of the company’s dubbing services, and written by Don and Cindy Hewitt, who had written other dubs for Ghibli films, including Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, Porco Rosso, Whisper of the Heart, and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

Disney’s English-language dub premiered on October 23, 2005; it then appeared at the 2005 Hollywood Film Festival. The Turner Classic Movies cable television network held the television premiere of Disney’s new English dub on January 19, 2006, as part of the network’s salute to Hayao Miyazaki. (TCM aired the dub as well as the original Japanese with English subtitles.) The Disney version was initially released on DVD in the United States on March 7, 2006, but is now out of print. This version of the film has since been used in all English-speaking regions and is one of the two versions most widely available, especially for streaming on Netflix and HBO Max.

Home media[edit]

The film was released to VHS and LaserDisc by Tokuma Shoten in August 1988 under their Animage Video label. Buena Vista Home Entertainment Japan (now Walt Disney Japan) would later reissue the VHS on June 27, 1997 as part of their Ghibli ga Ippai series, and was later released to DVD on September 28, 2001, including both the original Japanese and the Streamline Pictures English dub. Disney would later release the film on Blu-ray in the country on July 18, 2012. The DVD was re-released on July 16, 2014, using the remastered print from the Blu-ray and having the Disney produced English dub instead of Streamline’s.

In 1993, Fox Video licensed the film from Studio Ghibli and released the Streamline Pictures dub of My Neighbor Totoro on VHS and LaserDisc in the United States and was later released to DVD in 2002. After the rights to the dub expired in 2004, Walt Disney Home Entertainment re-released the movie on DVD on March 7, 2006 with Disney’s newly produced English dub and the original Japanese version. A reissue of Totoro, Castle in the Sky, and Kiki’s Delivery Service featuring updated cover art highlighting its Studio Ghibli origins was released by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment on March 2, 2010, coinciding with the US DVD and Blu-ray debut of Ponyo, and was subsequently released by Disney on Blu-Ray Disc on May 21, 2013. GKIDS re-issued the film on Blu-ray and DVD on October 17, 2017.[27]

The Disney-produced dub has also been released onto DVD and Blu-ray by distributors like Madman Entertainment in Australia and Optimum Releasing/StudioCanal UK in the United Kingdom.

In Japan, the film sold 3.5 million VHS and DVD units as of April 2012,[28] equivalent to approximately ¥16,100 million ($202 million) at an average retail price of ¥4,600 (¥4,700 on DVD and ¥4,500 on VHS).[29] In the United States, the film sold over 500,000 VHS units by 1996,[30] equivalent to approximately $10 million at a retail price of $19.98,[31] with the later 2010 DVD release selling a further 3.8 million units and grossing $64.5 million in the United States as of October 2018.[32] In total, the film’s home video releases have sold 7.8 million units and grossed an estimated $277 million in Japan and the United States.

In the United Kingdom, the film’s Studio Ghibli anniversary release appeared on the annual lists of top ten best-selling foreign language films on home video for five consecutive years, ranking number seven in 2015,[33] number six in 2016[34] and 2017,[35] number one in 2018,[36] and number two in 2019 (below Spirited Away).[37]

Reception[edit]