Русские хороводы распределены по времени года, свободным дням жизни.

Хороводы начинаются

со Святой недели и продолжаются до

рабочей поры; другие появляются с 15

августа и оканчиваются при наступлении

зим.

Первые

весенние хороводы начинаются

со Святой недели и оканчиваются вечером

на Красную горку. Здесь соединялись с

хороводами: встреча весны, снаряжение

суженых к венечному поезду.

Радуницкие

хороводы отличаются

разыгрыванием Вьюнца, старого народного

обряда в честь новобрачных.

Георгиевские

хороводы соединяют

с собой выгон скота на пастьбы и игры

на полях. В этот день к хороводницам

присоединяются гудочники—люди, умеющие

играть на рожке все сельские песни.

Последними весенними хороводами

считаются Никольские.

Летние

хороводы начинаются

с Троицкой недели и бывают веселее и

разнообразнее весенних. Поселянки

закупают наряды: платки и ленты. Московский

семик, первенец троицких хороводов,

отправляется во всеми увеселениями. К

этому дню мужчины рубят березки, женщины

красят желтые яйца, готовят караваи,

сдобники, драчены, яичницы. С рассветом

дня начинались игры и песни. Троицкие

хороводы продолжаются всю неделю.

Всесвятские хороводы продолжаются три

дня и соединены с особенными местными

празднествами.

Петровские

и Пятницкие хороводы отправляются

почти в одно и то же время. Начатие и

продолжение их зависит от изменяемости

нашего месяцеслова. Ивановские хороводы

начинаются 23 июня и продолжаются двое

суток.

Осенние

хороводы в

одних местах начинаются с Ильина дня,

а в других с Успеньева дня. Сельские

хороводы начинаются с бабьего лета.

Семенинские хороводы отправляются по

всей России с разными обрядами и

продолжаются целую неделю. Капустинские

хороводы начинаются с половины сентября

и отправляются только в городах. Последние

хороводы бывают покровские, и отправление

их зависит от времени года.

Русские

хороводы сопровождаются особенными

песнями и играми. Игры хороводные

содержат в себе драматическую жизнь

нашего народа. Здесь семейная жизнь

олицетворена в разных видах. В хороводах,

исключительно взятых, заключается

народная опера. Ее характер, исполненный

местными обрядами, старыми поверьями,

принадлежит включительно русскому

народу.

Не

просто танец, а сама жизнь, символ

вселенского лада – таков русский

хоровод. Больше всего «хождений под

песню» совершали после Пасхи и до Петрова

дня, потом уж было не до хороводов.

Сотни

названий,– «Русая коса», «Веночки»,

«Яртынь-трава» и др., — и четкое следование

заданной структуре танца, непременно

включающей 7 сакральных фигур – таков

он, русский хоровод.

-

«Столбы»

Участники

хоровода образуют неподвижный квадрат,

который затем приходит в движение. Те,

кто находится сзади, по трое выходят

чуть в сторону, обходят остальных и

встают в начало квадрата. Движение

продолжается до тех пор, пока не

переместятся все. Фигура «столб»

символизировала единство земли и неба,

женского и мужского начала, которые,

приходя в движение и перемешиваясь,

формируют Вселенную.

-

«Вожжа»

Участники

хоровода образуют волнистые линии,

которые вскоре начинают постепенно

уменьшаться в амплитуде, в итоге

превращаясь в точку. Именно волнистые

линии олицетворяют волны океана Хаоса,

из которого появляется новое рожденное,

и в который уходит старое умершее. Как

тут не задуматься о «ладности» своей

жизни и не воспользоваться случаем

прямо в хороводе начать ее править «в

лад».

-

«Плетень»

Название

этой фигуры – не случайно. Подобно

мастеровому, начинающему изготовление

плетня от исходной точки, участники

хоровода расходятся от центра, образуя

с каждой секундой увеличивающиеся

спирали, которые символично иллюстрируют

процесс Творения Вселенной. Глядя на

происходящее, волей-неволей начнешь

«проигрывать» свою жизнь, задумаешься

о правильности выбранного пути и его

корректировках.

-

«Круг».

Символизм

круга не ограничивается двумя определениями

– это и завершение Творения, и Совершенство,

и Гармония, и вечное Время, и Вселенная,

и Бог, и бессмертная Душа. Во время

исполнения этой фигуры участники создают

круговые петли, образующие «узелки» и

«заломы», которые необходимо непременно

распутать и разгладить, подобно

трудностям, возникающим на протяжении

всей человеческой жизни.

-

«Сторона

на сторону»

Во

время исполнения этой фигуры мужчины

выстраиваются в шеренгу напротив женщин.

Затем начинается поочередное схождение

«двух начал» и их общение. Женщины как

бы случайно роняют платки и венки, а

мужчины поднимают и возвращают потери

хозяйкам. Они поправляют одежду друг

на друге и расходятся только для того,

чтобы через мгновение снова сойтись.

Эта фигура прекрасно иллюстрирует, что

все в мире существует только благодаря

взаимодействию двух начал – небесного

мужского и земного женского. Эта фигура

отличается особенной плавностью и

размеренностью, показывающим умение

жить в гармонии с окружающими людьми и

самим собой.

-

«На

четыре стороны».

Предпоследняя

фигура призвана показать завершающий

этап формирования Вселенной. Участники

образуют квадрат, стороны которого

символизируют четыре стороны света.

Устойчивый и гармоничный квадрат как

нельзя лучше отражает состояние мира

во времени и пространстве. Одним из

элементов этой фигуры становятся

символичные движения – участники на

четыре стороны «сеют просо», чтобы

вскоре «собрать урожай».

-

«Плясовая»

С

каждой фигурой движение хоровода

ускоряется, и к своему завершению

сакральный танец приобретает залихватскую

удаль, наполняется юмором и радостью.

Во время плясовой части хоровода

исполняются самые любимые народные

танцы, сопровождает которые удалой

гармонист. Лучшие танцоры начинают

солировать, ловко и неподражаемо

демонстрируя свои способности. Это

момент осознания своей сущности, своего

места и своего предназначения.

Заикин

Н. И., Заикина Н. А. Областные особенности

русского народного танца. – Орел, 1999.

2.

Климов А. Основы русского народного

танца. – М.: Московского государственного

института культуры, 1994.

3.

Устинова Т. А. Избранные русские народные

танцы. – М.: Искусство, 1996.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Circle dance, or chain dance, is a style of social dance done in a circle, semicircle or a curved line to musical accompaniment, such as rhythm instruments and singing, and is a type of dance where anyone can join in without the need of partners. Unlike line dancing, circle dancers are in physical contact with each other; the connection is made by hand-to-hand, finger-to-finger or hands-on-shoulders, where they follow the leader around the dance floor. Ranging from gentle to energetic, the dance can be an uplifting group experience or part of a meditation.

Being probably the oldest known dance formation, circle dancing is an ancient tradition common to many cultures for marking special occasions, rituals, strengthening community and encouraging togetherness. Circle dances are choreographed to many different styles of music and rhythms. Modern circle dance mixes traditional folk dances, mainly from European or Near Eastern sources, with recently choreographed ones to a variety of music both ancient and modern. There is a growing repertoire of new circle dances to classical music and contemporary songs.[1]

Distribution[edit]

Modern circle dancing is found in many cultures, including Arabic (Levantian and Iraqi), Israeli (see Jewish dance and Israeli folk dancing),Luri, Assyrian, Kurdish, Turkish, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Maltese, and Balkan. It also found in South Asia such as Nati of Himachal Pradesh, Harul of Uttarakhand, Wanvun of Kashmir, Jhumair of Jharkhand and Fugdi of Goa. Despite its immense reputation in the Middle East and southeast Europe, circle dancing also has a historical prominence in Brittany, Catalonia and Ireland to the west of Europe, and also in South America (Peruvian), Tibet, and with Native Americans (see ghost dance). It is also used, in its more meditative form, in worship within various religious traditions including the Church of England[2] and the Islamic Haḍra Dhikr (or Zikr) dances.[3]

History[edit]

Balkans[edit]

Stecak from Radimlja, Hercegovina showing linked figures

Medieval tombstones called «Stećci» (singular «Stecak») in Bosnia and Hercegovina, dating from the end of the 12th century to the 16th century, bear inscriptions and figures which look like dancers in a chain. Men and women are portrayed dancing together holding hands at shoulder level but occasionally the groups consist of only one sex.[4][5]

In Macedonia, near the town of Zletovo, the murals on the monastery of Lesnovo (Lesnovo Manastir), which date from the 14th century, show a group of young men linking arms in a round dance.[6] A chronicle from 1344 urges the people of the city of Zadar to sing and dance circle dances for a festival. However, a reference comes from Bulgaria, in a manuscript of a 14th-century sermon, which called chain dances «devilish and damned.»[7]

Central Europe[edit]

The circle dance of Germany is called «Reigen»; it dates from the 10th century, and may have originated from devotional dances at early Christian festivals. Dancing around the church or a fire was frequently denounced by church authorities which only underscores how popular it was.[8][9] One of the frescos (dating from the 14th century) in Tyrol, at Runkelstein Castle, depicts Elisabeth of Poland, Queen of Hungary leading a chain dance.[10][11] Circle dances were also found in Czech Republic, dating to the 15th century. Dancing was primarily done around trees on the village green.[12] In Poland as well the earliest village dances were in circles or lines accompanied by the singing or clapping of the participants.[13]

Mediterranean[edit]

In the 14th century, Giovanni Boccaccio describes men and women circle dancing to their own singing or accompanied by musicians.[14] One of the frescos in Siena by Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted in 1338–1340 show a group of women doing a «bridge» figure while accompanied by another woman playing the tambourine.[15]

There are accounts of two western European travelers to Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. In 1577, Salomon Schweigger describes the events at a Greek wedding:[16]

then they joined arms one upon the other, made a circle, went round the circle, with their feet stepping hard and stamping; one sang first, with the others all following after.[16]

Another traveler, the German pharmacist Reinhold Lubenau, was in Constantinople in November 1588 and reports on a Greek wedding in these terms:[17]

a company of Greeks, often of ten or more persons, stepped forth to the open place, took each other by the hand, made a round circle, and now stepped backward, now forward, sometimes went around, singing in Greek the while, sometimes stamped strongly on the ground with their feet.[17]

Scandinavia[edit]

Fresco at Ørslev church, Denmark showcasing a medieval form of chain dancing

In Denmark, old ballads mention a closed circle dance which can open into a chain dance. A fresco in Ørslev church in Zealand from about 1400 shows nine people, men and women, dancing in a line. The leader and some others in the chain carry bouquets of flowers. In the case of women’s dances, there may have been a man who acted as the leader.[18][19] In Sweden, medieval songs often mentioned dancing. A long chain was formed, with the leader singing the verses and setting the time while the other dancers joined in the chorus.[20]

Modern dances[edit]

Eastern Europe[edit]

Hora[edit]

The Hora dance originates in the Balkans but is also found in other countries (including Romania and Moldova). The dancers hold each other’s hands and the circle spins, usually counterclockwise, as each participant follows a sequence of three steps forward and one step back. The Hora is popular during wedding celebrations and festivals, and is an essential part of social entertainment in rural areas. In Bulgaria, it is not necessary to be in a circle; a curving line of people is also acceptable.[21]

Kolo[edit]

The Kolo is a collective folk dance common in various South Slavic regions, such as Serbia and Bosnia, named after the circle formed by the dancers. It is performed amongst groups of people (usually several dozen, at the very least three) holding each other’s having their hands around each other’s waists (ideally in a circle, hence the name). There is almost no movement above the waist.[22][23]

Southern Europe[edit]

Kalamatianos[edit]

The Kalamatianos is a popular Greek folkdance throughout Greece and Cyprus, and is often performed at many social gatherings worldwide. As is the case with most Greek folk dances, it is danced in a circle with a counterclockwise rotation, the dancers holding hands. The lead dancer usually holds the second dancer by a handkerchief, thus allowing more elaborate steps and acrobatics. The steps of the Kalamatianós are the same as those of the Syrtos, but the latter is slower and more stately, its beat being a steady 4

4.[24]

Sardana[edit]

Sardana is a type of circle dance typical of Catalonia. It would usually have an experienced dancer leading the circle. The dancers hold hands throughout the dance: arms down during the curts and raised to shoulder height during the llargs. The dance was originally from the Empordà region, but started gaining popularity throughout Catalonia during the 20th century. There are two main types, the original Sardana curta (short Sardana) style and the more modern Sardana llarga (long Sardana).[25]

Syrtos[edit]

Syrtos and Kalamatianos are Greek dances done with the dancers in a curving line holding hands, facing right. The dancer at the right end of the line is the leader. The leader can also be a solo performer, improvising showy twisting skillful moves as the rest of the line does the basic step. In some parts of Syrtos, pairs of dancers hold a handkerchief from its two sides.[26][27]

Western Europe[edit]

An Dro[edit]

An Dro, meaning «the turn», is a Breton circle dance. The dancers link the little fingers in a long line, swinging their arms, whilst moving to their left. The arm movements consist first of two circular motions going up and back followed by one in the opposite direction. The leader (person at the left-hand end of the line) will lead the line into a spiral or double it back on itself to form patterns on the dance floor, and allow the dancers to see each other.[28]

Faroese chain dance[edit]

The Faroese chain dance is the national circle dance of the Faroe Islands. The dance originated in medieval times, and survived only in the Faroe Islands, while in other European countries it was banned by the church, due to its pagan origin. The dance is danced traditionally in a circle, but when a lot of people take part in the dance they usually let it swing around in various wobbles within the circle. The dance in itself only consists in holding each other’s hands, while the dancers form a circle, dancing two steps to the left and one to the right without crossing the legs. When more and more dancers join the dance vine, the circle starts to bend and forms a new one within itself.[29]

Sacred Circle Dance[edit]

The Sacred Circle Dance was brought to the Findhorn Foundation community in Scotland by Bernhard Wosien; he presented traditional circle dances that he had gathered from across Eastern Europe.[30] Colin Harrison and David Roberts and Janet Rowan Scott took the dances to other parts of the United Kingdom where they started regular groups in south east England, then across Europe, the US and elsewhere. The network extends also to Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, South America, and India. A small centrepiece of flowers or other objects is often placed at the centre of the circle to help focus the dancers and maintain the circular shape. Much debate goes on within the sacred circle dance network about what is meant by ‘sacred’ in the dance.[31]

Middle East[edit]

Dabke[edit]

Dabke is popular in Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Israel, Jordan and Turkey. The most famous type of the dance is the Al-Shamaliyya (الشمالية). It consists of a lawweeh (لويح) at the head of a group of men holding hands and formed in a semicircle. The lawweeh is expected to be particularly skilled in accuracy, ability to improvise, and quickness (generally light on his feet). The dancers develop a synchronized movement and step, and when the singers finish their song the lawweeh breaks from the semicircle to dance on their own. The lawweeh is the most popular and familiar form of dabke danced for happy family celebrations.[32]

Govend[edit]

Govend is one of the most famous traditional Kurdish dances.[33] It is distinguished from other Middle Eastern dances by being for both men and women.[34]

Khigga[edit]

Khigga is the one of main styles of Assyrian folk dance in which multiple dancers hold each other’s hands and form a line or a circle. It is usually performed at weddings and joyous occasions. Khigga is the first beat that is played in welcoming the bride and groom to the reception hall. There are multiple foot patterns that dancers perform. The head of the khigga line usually dances with a handkerchief with beads and bells added to the sides so it jingles when shaken. A decorated cane is also used at many Assyrian weddings. Moreover, the term khigga is used to denote all the Assyrian circle dances.[35]

Kochari[edit]

Kochari is an Armenian[36][37][38] folk dance, danced today by Armenians, Assyrians,[39] Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Pontic Greeks[40] and Turks.[41] Dancers form a closed circle, putting their hands on each other’s shoulders. More modern forms of Kochari have added a «tremolo step,» which involves shaking the whole body. In Azerbaijan, the dance consists of slow and rapid parts, and is of three variants. There is a consistent, strong double bounce. Pontic Greeks dance hand-to-shoulder and travel to the right.[42][43]

Tamzara[edit]

Tamzara is an Armenian, Assyrian,and Greek folk dance native to Anatolia. There are many versions of Tamzara, with slightly different music and steps, coming from the various regions and old villages in Anatolia. Firstly they take three steps forwards, tap their left feet on the ground, and step forward to stand on the left foot; then they take three small steps back and repeat the actions a little faster. Like most Anatolian folk dances, Tamzara is done with a large group of people with interlocked little fingers.[44]

prevalent in south Asia in Himachal Pradesh, Kashmir,

South Asia[edit]

Circle dance is prevalent in Himalaya region of North-west India and Central India. Some circle dance of South Asia are Nati of Himachal Pradesh, Harul of Uttarakhand, Wanvun of Kashmir, folk dance of Kalash people of Chitral District, Jhumair dance of Jharkhand and Fugdi dance of Goa.[45][46][47][48]

Fugdi Dancers from South Goa

See also[edit]

- International folk dance

- Bunny hop

References[edit]

- ^ Gilbert, Cecile (1974). International Folk Dance at a Glance (Second ed.). Burgess. ISBN 978-0808707271.

- ^ «We ended with a circle dance.» «A short session of circle dance was one of the activities on offer…»«Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Chivers, C. J. (24 May 2006). «A Whirling Sufi Revival With Unclear Implications». The New York Times. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

Three circles of barefoot men, one ring inside another, sway to the cadence of chant. The men stamp in time as they sway, and grunt from the abdomen and throat, filling the room with a primal sound. One voice rises over the rest, singing variants of the names of God.

- ^ Alojz Benac «Chapter XIII: Medieval Tombstones (Stećci)» in Bihalji-Merin, Otto, ed. (1969). Art Treasures of Yugoslavia. New York: Abrams. pp. 277–296.

- ^ Bihalji-Merin, Otto; Benac, Alojz (1962). The Bogomils. London: Thames.

- ^ «Historical view on the Lesnovo monastery». Ilija Velev (University of Skopje). Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ Katzarova-Kukudova, Raina; Djenev, Kiril (1958). Bulgarian Folk Dances. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Slavica. p. 9.

- ^ Goldschmidt, Aenne (1978). Handbuch des Deutschen Volktanzes. Wilhelmshaven: Heinrichshofen. p. 27.

- ^ Fyfe, Agnes (1951). Dances of Germany. London: Max Parrish. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Martin, György (1974). Hungarian Folk Dances. Budapest: Corvina Press. p. 17.

- ^ «Runkelstein Castle — The illustrated castle A short history». Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Lubinová, Mila (1949). Dances of Czechoslovakia. New York: Chanticleer Press. p. 8.

- ^ Dziewanowska, Ada (1997). Polish Folk Dances and Songs. New York: Hippocrene. p. 26. ISBN 0-7818-0420-5.

- ^ Nosow, Robert (1985). «Dancing the Righoletto». Journal of Musicology. 24 (3): 407–446. doi:10.1525/jm.2007.24.3.407.

- ^ Bragaglia, Anto Giulio (1952). Danze popolari italiane [Popular Italian Dances] (in Italian). Roma: Edizioni Enal.

- ^ a b Schweigger, Salomon (1964). Ein newe Reyssbeschreibung auss Teutschland nach Constantinopel und Jerusalem. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt. p. 227.

- ^ a b Lubenau, Reinhold (1915). Sahm, W. (ed.). «Beschreibung der Reisen des Reinhold Lubenau» [Account of the Journes of Reinhold Lubenau]. Mitteilungen aus der Stadtbibliothek zu Koenigsberg i. Pr. (in German). VI: 23.

- ^ Lorenzen, Poul; Jeppesen, Jeppe (1950). Dances of Denmark. New York: Chanticleer Press. pp. 7–10.

- ^ Curt Sachs (1963) World History of the Dance, p.263

- ^ Salvén, Erik (1949). Dances of Sweden. London: Max Parrish. p. 8.

- ^ «‘Hora’ History». forward.com. 12 December 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Costumes. (2009). In ASKA Kolo Ansambl. Retrieved March 26, 2009, from ASKA Kolo Ansambl «ASKA Kolo Ansambl in Sacramento, California — Home». Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ kolo. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 March 2009, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/321451/kolo

- ^ Lykesas, George H. (1993). Οι Ελληνικοί Χοροί [Greek Dances] (in Greek) (Second ed.). Thessaloniki: University Studio Press.

- ^ «Origin of the Sardana» (in Spanish). Lavanguardia.es. 16 March 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ σύρω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ συρτός Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Bacher, Elsa; Ruling, Ruth (March 1998). «An Dro Retourne» (PDF). Folk Dance Federation of California. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ «Faroese Chain Dance». Faroe Islands.fo. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Watts, June (2006). Circle Dancing — Celebrating the Sacred in Dance. Green Magic Publishing. pp. 6–10. ISBN 0-9547230-8-2.

- ^ See many issues of Grapevine over its 25 years history, available via www.circledancenetwork.org.uk

- ^ «Dabke: The Dance of the Lebanese Village». Sourat. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ «Kurdish Dance». The Kurdish Project. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ «17th Annual Smithsonian Magazine Photo Contest: Travel: Kurdish Dance». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ BetBasoo, Peter Pnuel (30 April 2003). «Thirty Assyrian Folk Dances» (PDF).

- ^ Elia, Anthony J. (2013). «Kochari (Old Armenian Folk Tune) for Solo Piano». Center for Digital Research and Scholarship at Columbia University. doi:10.7916/D8S75QNP. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Vvedensky, Boris, ed. (1953). Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). Vol. 23 (Second ed.). Moscow: Soviet Encyclopedia. p. 170.

КОЧАРИ — армянский народный мужской танец.

- ^ Yuzefovich, Victor (1985). Aram Khachaturyan. New York: Sphinx Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0823686582.

..and in the sixth scene one of the dances of the gladiators is very reminiscent of Kochari, the Armenian folk dance.

- ^ BetBasoo, Peter Pnuel (30 April 2003). «Thirty Assyrian Folk Dances» (PDF). Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ «Kotsari». Pontian.info. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Ю.В. Келдыш, М.Г. Арановский, Л.З.Корабельникова (1990). Kochari — Musical Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). Soviet Encyclopedia. p. 275.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «The National Dancings». Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Hellander, Paul (2008). Greece. Kate Armstrong, Michael Clark, Des Hannigan, Victoria Kyriakopoulos, Miriam Raphael, Andrew Ston. Lonely Planet. p. 67. ISBN 978-1741046564.

- ^ «PontosWorld». pontosworld.com. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ «Himachal Pradesh Dances — Folk Dances of Himachal Pradesh, Traditional Dance Himachal Pradesh India». Bharatonline. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Bisht, Ruchi. «Glocal Colloquies» (PDF). Global Colloquies: 134. ISSN 2454-2423.

- ^ «Out of the Dark». democratic world.

- ^ «Goan Folk Arts». Goajourney. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

Journals[edit]

- Drumbeat, the South African circle dancing journal.

- Grapevine, the quarterly journal of Circle Dance Friends. ISSN 1752-4660

Further reading[edit]

- Laura Hellsten, Laura (2021) Through the Bone and Marrow — Re-examining Theological Encounters with Dance in Medieval Europe. Brepols.

- Kathryn Dickason (2020) Ringleaders of Redemption — How Medieval Dance Became Sacred. Oxford University Press.

- Lynn Frances and Richard Bryant-Jefferies (1998) The Sevenfold Circle: self awareness in dance, Findhorn Press. ISBN 1-899171-37-1

- Marion Violets Gibson (2006) Dancing on Water, printed in Wales. ISBN 0-905285-79-4

- Matti Goldschmidt, The Bible in Israeli Folk Dances, Ed. Choros

- Judy King, The Dancing Circle, volumes 1–4, Sarsen Press, Winchester, England

- Iris J Stewart (2000) Sacred Woman Sacred Dance: Awakening spirituality through movement and ritual, Inner Traditions, USA ISBN 978-1-62055-054-0

- Bernhard Wosien, Journey of a Dancer (2016) Sarsen Press, Winchester, England.

- Maria-Gabriele Wosien, Sacred Dance: Encounter with the Gods (1986) [1974] Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-81006-0

External links[edit]

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Circle dance, or chain dance, is a style of social dance done in a circle, semicircle or a curved line to musical accompaniment, such as rhythm instruments and singing, and is a type of dance where anyone can join in without the need of partners. Unlike line dancing, circle dancers are in physical contact with each other; the connection is made by hand-to-hand, finger-to-finger or hands-on-shoulders, where they follow the leader around the dance floor. Ranging from gentle to energetic, the dance can be an uplifting group experience or part of a meditation.

Being probably the oldest known dance formation, circle dancing is an ancient tradition common to many cultures for marking special occasions, rituals, strengthening community and encouraging togetherness. Circle dances are choreographed to many different styles of music and rhythms. Modern circle dance mixes traditional folk dances, mainly from European or Near Eastern sources, with recently choreographed ones to a variety of music both ancient and modern. There is a growing repertoire of new circle dances to classical music and contemporary songs.[1]

Distribution[edit]

Modern circle dancing is found in many cultures, including Arabic (Levantian and Iraqi), Israeli (see Jewish dance and Israeli folk dancing),Luri, Assyrian, Kurdish, Turkish, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Maltese, and Balkan. It also found in South Asia such as Nati of Himachal Pradesh, Harul of Uttarakhand, Wanvun of Kashmir, Jhumair of Jharkhand and Fugdi of Goa. Despite its immense reputation in the Middle East and southeast Europe, circle dancing also has a historical prominence in Brittany, Catalonia and Ireland to the west of Europe, and also in South America (Peruvian), Tibet, and with Native Americans (see ghost dance). It is also used, in its more meditative form, in worship within various religious traditions including the Church of England[2] and the Islamic Haḍra Dhikr (or Zikr) dances.[3]

History[edit]

Balkans[edit]

Stecak from Radimlja, Hercegovina showing linked figures

Medieval tombstones called «Stećci» (singular «Stecak») in Bosnia and Hercegovina, dating from the end of the 12th century to the 16th century, bear inscriptions and figures which look like dancers in a chain. Men and women are portrayed dancing together holding hands at shoulder level but occasionally the groups consist of only one sex.[4][5]

In Macedonia, near the town of Zletovo, the murals on the monastery of Lesnovo (Lesnovo Manastir), which date from the 14th century, show a group of young men linking arms in a round dance.[6] A chronicle from 1344 urges the people of the city of Zadar to sing and dance circle dances for a festival. However, a reference comes from Bulgaria, in a manuscript of a 14th-century sermon, which called chain dances «devilish and damned.»[7]

Central Europe[edit]

The circle dance of Germany is called «Reigen»; it dates from the 10th century, and may have originated from devotional dances at early Christian festivals. Dancing around the church or a fire was frequently denounced by church authorities which only underscores how popular it was.[8][9] One of the frescos (dating from the 14th century) in Tyrol, at Runkelstein Castle, depicts Elisabeth of Poland, Queen of Hungary leading a chain dance.[10][11] Circle dances were also found in Czech Republic, dating to the 15th century. Dancing was primarily done around trees on the village green.[12] In Poland as well the earliest village dances were in circles or lines accompanied by the singing or clapping of the participants.[13]

Mediterranean[edit]

In the 14th century, Giovanni Boccaccio describes men and women circle dancing to their own singing or accompanied by musicians.[14] One of the frescos in Siena by Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted in 1338–1340 show a group of women doing a «bridge» figure while accompanied by another woman playing the tambourine.[15]

There are accounts of two western European travelers to Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. In 1577, Salomon Schweigger describes the events at a Greek wedding:[16]

then they joined arms one upon the other, made a circle, went round the circle, with their feet stepping hard and stamping; one sang first, with the others all following after.[16]

Another traveler, the German pharmacist Reinhold Lubenau, was in Constantinople in November 1588 and reports on a Greek wedding in these terms:[17]

a company of Greeks, often of ten or more persons, stepped forth to the open place, took each other by the hand, made a round circle, and now stepped backward, now forward, sometimes went around, singing in Greek the while, sometimes stamped strongly on the ground with their feet.[17]

Scandinavia[edit]

Fresco at Ørslev church, Denmark showcasing a medieval form of chain dancing

In Denmark, old ballads mention a closed circle dance which can open into a chain dance. A fresco in Ørslev church in Zealand from about 1400 shows nine people, men and women, dancing in a line. The leader and some others in the chain carry bouquets of flowers. In the case of women’s dances, there may have been a man who acted as the leader.[18][19] In Sweden, medieval songs often mentioned dancing. A long chain was formed, with the leader singing the verses and setting the time while the other dancers joined in the chorus.[20]

Modern dances[edit]

Eastern Europe[edit]

Hora[edit]

The Hora dance originates in the Balkans but is also found in other countries (including Romania and Moldova). The dancers hold each other’s hands and the circle spins, usually counterclockwise, as each participant follows a sequence of three steps forward and one step back. The Hora is popular during wedding celebrations and festivals, and is an essential part of social entertainment in rural areas. In Bulgaria, it is not necessary to be in a circle; a curving line of people is also acceptable.[21]

Kolo[edit]

The Kolo is a collective folk dance common in various South Slavic regions, such as Serbia and Bosnia, named after the circle formed by the dancers. It is performed amongst groups of people (usually several dozen, at the very least three) holding each other’s having their hands around each other’s waists (ideally in a circle, hence the name). There is almost no movement above the waist.[22][23]

Southern Europe[edit]

Kalamatianos[edit]

The Kalamatianos is a popular Greek folkdance throughout Greece and Cyprus, and is often performed at many social gatherings worldwide. As is the case with most Greek folk dances, it is danced in a circle with a counterclockwise rotation, the dancers holding hands. The lead dancer usually holds the second dancer by a handkerchief, thus allowing more elaborate steps and acrobatics. The steps of the Kalamatianós are the same as those of the Syrtos, but the latter is slower and more stately, its beat being a steady 4

4.[24]

Sardana[edit]

Sardana is a type of circle dance typical of Catalonia. It would usually have an experienced dancer leading the circle. The dancers hold hands throughout the dance: arms down during the curts and raised to shoulder height during the llargs. The dance was originally from the Empordà region, but started gaining popularity throughout Catalonia during the 20th century. There are two main types, the original Sardana curta (short Sardana) style and the more modern Sardana llarga (long Sardana).[25]

Syrtos[edit]

Syrtos and Kalamatianos are Greek dances done with the dancers in a curving line holding hands, facing right. The dancer at the right end of the line is the leader. The leader can also be a solo performer, improvising showy twisting skillful moves as the rest of the line does the basic step. In some parts of Syrtos, pairs of dancers hold a handkerchief from its two sides.[26][27]

Western Europe[edit]

An Dro[edit]

An Dro, meaning «the turn», is a Breton circle dance. The dancers link the little fingers in a long line, swinging their arms, whilst moving to their left. The arm movements consist first of two circular motions going up and back followed by one in the opposite direction. The leader (person at the left-hand end of the line) will lead the line into a spiral or double it back on itself to form patterns on the dance floor, and allow the dancers to see each other.[28]

Faroese chain dance[edit]

The Faroese chain dance is the national circle dance of the Faroe Islands. The dance originated in medieval times, and survived only in the Faroe Islands, while in other European countries it was banned by the church, due to its pagan origin. The dance is danced traditionally in a circle, but when a lot of people take part in the dance they usually let it swing around in various wobbles within the circle. The dance in itself only consists in holding each other’s hands, while the dancers form a circle, dancing two steps to the left and one to the right without crossing the legs. When more and more dancers join the dance vine, the circle starts to bend and forms a new one within itself.[29]

Sacred Circle Dance[edit]

The Sacred Circle Dance was brought to the Findhorn Foundation community in Scotland by Bernhard Wosien; he presented traditional circle dances that he had gathered from across Eastern Europe.[30] Colin Harrison and David Roberts and Janet Rowan Scott took the dances to other parts of the United Kingdom where they started regular groups in south east England, then across Europe, the US and elsewhere. The network extends also to Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, South America, and India. A small centrepiece of flowers or other objects is often placed at the centre of the circle to help focus the dancers and maintain the circular shape. Much debate goes on within the sacred circle dance network about what is meant by ‘sacred’ in the dance.[31]

Middle East[edit]

Dabke[edit]

Dabke is popular in Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Israel, Jordan and Turkey. The most famous type of the dance is the Al-Shamaliyya (الشمالية). It consists of a lawweeh (لويح) at the head of a group of men holding hands and formed in a semicircle. The lawweeh is expected to be particularly skilled in accuracy, ability to improvise, and quickness (generally light on his feet). The dancers develop a synchronized movement and step, and when the singers finish their song the lawweeh breaks from the semicircle to dance on their own. The lawweeh is the most popular and familiar form of dabke danced for happy family celebrations.[32]

Govend[edit]

Govend is one of the most famous traditional Kurdish dances.[33] It is distinguished from other Middle Eastern dances by being for both men and women.[34]

Khigga[edit]

Khigga is the one of main styles of Assyrian folk dance in which multiple dancers hold each other’s hands and form a line or a circle. It is usually performed at weddings and joyous occasions. Khigga is the first beat that is played in welcoming the bride and groom to the reception hall. There are multiple foot patterns that dancers perform. The head of the khigga line usually dances with a handkerchief with beads and bells added to the sides so it jingles when shaken. A decorated cane is also used at many Assyrian weddings. Moreover, the term khigga is used to denote all the Assyrian circle dances.[35]

Kochari[edit]

Kochari is an Armenian[36][37][38] folk dance, danced today by Armenians, Assyrians,[39] Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Pontic Greeks[40] and Turks.[41] Dancers form a closed circle, putting their hands on each other’s shoulders. More modern forms of Kochari have added a «tremolo step,» which involves shaking the whole body. In Azerbaijan, the dance consists of slow and rapid parts, and is of three variants. There is a consistent, strong double bounce. Pontic Greeks dance hand-to-shoulder and travel to the right.[42][43]

Tamzara[edit]

Tamzara is an Armenian, Assyrian,and Greek folk dance native to Anatolia. There are many versions of Tamzara, with slightly different music and steps, coming from the various regions and old villages in Anatolia. Firstly they take three steps forwards, tap their left feet on the ground, and step forward to stand on the left foot; then they take three small steps back and repeat the actions a little faster. Like most Anatolian folk dances, Tamzara is done with a large group of people with interlocked little fingers.[44]

prevalent in south Asia in Himachal Pradesh, Kashmir,

South Asia[edit]

Circle dance is prevalent in Himalaya region of North-west India and Central India. Some circle dance of South Asia are Nati of Himachal Pradesh, Harul of Uttarakhand, Wanvun of Kashmir, folk dance of Kalash people of Chitral District, Jhumair dance of Jharkhand and Fugdi dance of Goa.[45][46][47][48]

Fugdi Dancers from South Goa

See also[edit]

- International folk dance

- Bunny hop

References[edit]

- ^ Gilbert, Cecile (1974). International Folk Dance at a Glance (Second ed.). Burgess. ISBN 978-0808707271.

- ^ «We ended with a circle dance.» «A short session of circle dance was one of the activities on offer…»«Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Chivers, C. J. (24 May 2006). «A Whirling Sufi Revival With Unclear Implications». The New York Times. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

Three circles of barefoot men, one ring inside another, sway to the cadence of chant. The men stamp in time as they sway, and grunt from the abdomen and throat, filling the room with a primal sound. One voice rises over the rest, singing variants of the names of God.

- ^ Alojz Benac «Chapter XIII: Medieval Tombstones (Stećci)» in Bihalji-Merin, Otto, ed. (1969). Art Treasures of Yugoslavia. New York: Abrams. pp. 277–296.

- ^ Bihalji-Merin, Otto; Benac, Alojz (1962). The Bogomils. London: Thames.

- ^ «Historical view on the Lesnovo monastery». Ilija Velev (University of Skopje). Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ Katzarova-Kukudova, Raina; Djenev, Kiril (1958). Bulgarian Folk Dances. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Slavica. p. 9.

- ^ Goldschmidt, Aenne (1978). Handbuch des Deutschen Volktanzes. Wilhelmshaven: Heinrichshofen. p. 27.

- ^ Fyfe, Agnes (1951). Dances of Germany. London: Max Parrish. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Martin, György (1974). Hungarian Folk Dances. Budapest: Corvina Press. p. 17.

- ^ «Runkelstein Castle — The illustrated castle A short history». Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Lubinová, Mila (1949). Dances of Czechoslovakia. New York: Chanticleer Press. p. 8.

- ^ Dziewanowska, Ada (1997). Polish Folk Dances and Songs. New York: Hippocrene. p. 26. ISBN 0-7818-0420-5.

- ^ Nosow, Robert (1985). «Dancing the Righoletto». Journal of Musicology. 24 (3): 407–446. doi:10.1525/jm.2007.24.3.407.

- ^ Bragaglia, Anto Giulio (1952). Danze popolari italiane [Popular Italian Dances] (in Italian). Roma: Edizioni Enal.

- ^ a b Schweigger, Salomon (1964). Ein newe Reyssbeschreibung auss Teutschland nach Constantinopel und Jerusalem. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt. p. 227.

- ^ a b Lubenau, Reinhold (1915). Sahm, W. (ed.). «Beschreibung der Reisen des Reinhold Lubenau» [Account of the Journes of Reinhold Lubenau]. Mitteilungen aus der Stadtbibliothek zu Koenigsberg i. Pr. (in German). VI: 23.

- ^ Lorenzen, Poul; Jeppesen, Jeppe (1950). Dances of Denmark. New York: Chanticleer Press. pp. 7–10.

- ^ Curt Sachs (1963) World History of the Dance, p.263

- ^ Salvén, Erik (1949). Dances of Sweden. London: Max Parrish. p. 8.

- ^ «‘Hora’ History». forward.com. 12 December 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Costumes. (2009). In ASKA Kolo Ansambl. Retrieved March 26, 2009, from ASKA Kolo Ansambl «ASKA Kolo Ansambl in Sacramento, California — Home». Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ kolo. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 March 2009, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/321451/kolo

- ^ Lykesas, George H. (1993). Οι Ελληνικοί Χοροί [Greek Dances] (in Greek) (Second ed.). Thessaloniki: University Studio Press.

- ^ «Origin of the Sardana» (in Spanish). Lavanguardia.es. 16 March 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ σύρω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ συρτός Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Bacher, Elsa; Ruling, Ruth (March 1998). «An Dro Retourne» (PDF). Folk Dance Federation of California. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ «Faroese Chain Dance». Faroe Islands.fo. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Watts, June (2006). Circle Dancing — Celebrating the Sacred in Dance. Green Magic Publishing. pp. 6–10. ISBN 0-9547230-8-2.

- ^ See many issues of Grapevine over its 25 years history, available via www.circledancenetwork.org.uk

- ^ «Dabke: The Dance of the Lebanese Village». Sourat. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ «Kurdish Dance». The Kurdish Project. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ «17th Annual Smithsonian Magazine Photo Contest: Travel: Kurdish Dance». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ BetBasoo, Peter Pnuel (30 April 2003). «Thirty Assyrian Folk Dances» (PDF).

- ^ Elia, Anthony J. (2013). «Kochari (Old Armenian Folk Tune) for Solo Piano». Center for Digital Research and Scholarship at Columbia University. doi:10.7916/D8S75QNP. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Vvedensky, Boris, ed. (1953). Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). Vol. 23 (Second ed.). Moscow: Soviet Encyclopedia. p. 170.

КОЧАРИ — армянский народный мужской танец.

- ^ Yuzefovich, Victor (1985). Aram Khachaturyan. New York: Sphinx Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0823686582.

..and in the sixth scene one of the dances of the gladiators is very reminiscent of Kochari, the Armenian folk dance.

- ^ BetBasoo, Peter Pnuel (30 April 2003). «Thirty Assyrian Folk Dances» (PDF). Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ «Kotsari». Pontian.info. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Ю.В. Келдыш, М.Г. Арановский, Л.З.Корабельникова (1990). Kochari — Musical Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). Soviet Encyclopedia. p. 275.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «The National Dancings». Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Hellander, Paul (2008). Greece. Kate Armstrong, Michael Clark, Des Hannigan, Victoria Kyriakopoulos, Miriam Raphael, Andrew Ston. Lonely Planet. p. 67. ISBN 978-1741046564.

- ^ «PontosWorld». pontosworld.com. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ «Himachal Pradesh Dances — Folk Dances of Himachal Pradesh, Traditional Dance Himachal Pradesh India». Bharatonline. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Bisht, Ruchi. «Glocal Colloquies» (PDF). Global Colloquies: 134. ISSN 2454-2423.

- ^ «Out of the Dark». democratic world.

- ^ «Goan Folk Arts». Goajourney. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

Journals[edit]

- Drumbeat, the South African circle dancing journal.

- Grapevine, the quarterly journal of Circle Dance Friends. ISSN 1752-4660

Further reading[edit]

- Laura Hellsten, Laura (2021) Through the Bone and Marrow — Re-examining Theological Encounters with Dance in Medieval Europe. Brepols.

- Kathryn Dickason (2020) Ringleaders of Redemption — How Medieval Dance Became Sacred. Oxford University Press.

- Lynn Frances and Richard Bryant-Jefferies (1998) The Sevenfold Circle: self awareness in dance, Findhorn Press. ISBN 1-899171-37-1

- Marion Violets Gibson (2006) Dancing on Water, printed in Wales. ISBN 0-905285-79-4

- Matti Goldschmidt, The Bible in Israeli Folk Dances, Ed. Choros

- Judy King, The Dancing Circle, volumes 1–4, Sarsen Press, Winchester, England

- Iris J Stewart (2000) Sacred Woman Sacred Dance: Awakening spirituality through movement and ritual, Inner Traditions, USA ISBN 978-1-62055-054-0

- Bernhard Wosien, Journey of a Dancer (2016) Sarsen Press, Winchester, England.

- Maria-Gabriele Wosien, Sacred Dance: Encounter with the Gods (1986) [1974] Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-81006-0

External links[edit]

Народный танец – душа народа, его верования и обычаи, дух и темперамент, чувства и надежды, быт. В русском народном танце отражается вся многогранность традиций и обрядов, стоящих на стыке православия и язычества. Один из самых красивых и тесно связанных с ритуальной стороной жизни древних славян народный танец – хоровод.

Хоровод (в старые времена его называли еще харагод, курагод, коло и др.) – это древний обрядовый круговой танец с элементами драматического действа.Как правило, его исполняли женщины, но бывали и смешанные хороводы.Первые весенние хороводы начинали водить со Святой недели (следующей за Пасхой) и заканчивали вечером на Красную горку. И все лето и осень по большим праздникам и по грустным поводам исполняли хоровод.

Танец, песня, игра здесь были неразлучны. Молодые в хороводе знакомились и влюблялись. Существовало два основных вида танца. В орнаментных хороводах особое внимание уделялось рисунку. Сюжетной линии в песне здесь не было, слова ее создавали, например, образ родной земли или описывали труд в поле. Отличался этот танец четкостью композиционных перестроений: из круга рисовались восьмерки, змейки, колонны. Вторая разновидность хороводов – игровые. Здесь в песне прослеживалась сюжетная линия, были действующие лица. Исполнители хоровода с помощью жестов, мимики и пляски воплощали песенную историю в жизнь.

Но в чем же сакральный смысл танца? Во-первых,круговая композиция подобна солнцу, богу которого поклонялись славяне-язычники. Во-вторых, в разное время года, на праздниках, танец выполнял разную функцию. Например, первыми весенними хороводами задабривали богов плодородия, в июле славили Купалу и просили его помочь созреванию плодов, на Троицу хоровод водили вокруг березки. Береза считалась символом красоты и чистоты, проводником энергии. Более того, береза была покровительницей семьи и домашнего очага и могла подарить плодородие. Девушки собирались в хороводы вокруг этого священного дерева, чтобы пробудить в нем силу и приобщиться к ней. Такие «хороводы силы» водили все лето и верили, что они помогут исцелиться, исполнить желание и даже защитить свою землю.

Особенно интересны традиции севера Руси. Там хоровод отличался от среднерусского. Интересно, что в селе Усть-Цильма Республики Коми во время Красных горок и в наши дни водят хоровод в старых традициях. По церковному календарю,»Горка» начиналась с Николы вешнего (22 мая), продолжалась в Троицу и в каждое воскресение, если позволяла погода, захватывала Иван день (7 июля) и заканчивалась в день первоверховных апостолов Петра и Павла (12 июля).

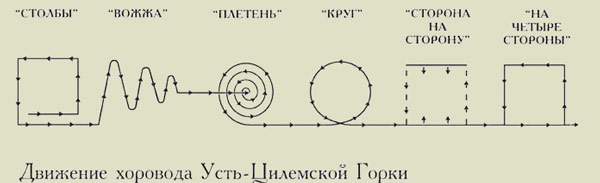

Горочное «хождение под песню» исполняется и мужчинами и женщинами всех возрастов в традиционных костюмах несколько раз в день, а в полном виде — вечером, завершая собой празднество. В танец заложено 17 различных фольклорных сюжетов. Во время него обязательно используются 7 символических фигур. Первая фигура – столбы. В ней участвуют только женщины. Это неподвижный квадрат, танцовщицы с конца которого по трое выходят чуть в сторону и, обойдя остальных, встают вначале. Продолжается до тех пор, пока так не пройдут все. Действо символизирует продолжение рода.

Первые шесть фигур Усть-Цилемского хоровода

Столбы переходят в вожжу. Участники движутся волнистой линией — змейкой — с постепенно уменьшающейся амплитудой, проходя под аркой, образованной руками первой пары. Затем наступает очередь плетня. Участники движутся по раскручивающейся из центра спирали. Затем колонна водящих хоровод делает петлю в виде круга. Следующая фигура Сторона на сторону — мужчины и женщины разделяются на две шеренги, которые то расходятся в разные стороны, то вновь сближаются. При этом девушки роняют платки и венки на землю, а юноши поднимают их и возвращают их хозяйкам. Эта хороводная игра изображает сватовство и женитьбу молодых. Шестая часть горочного обрядового танца — на четыре стороны — символизирует урожай. Называется она так потому, что все участники встают квадратом и начинают делать движения, показывающие, что они «сеют просо».В заключение начинается плясовая часть. Это уже не хоровод, не ритуал, а обыкновенные праздничные народные танцы под гармонь — барыня и кадриль.

Сколько земель, традиций, песен на Руси – столько и хороводов. И какими бы наивными не казались современному человеку задабривания богов плодородия или изгнания злых духов с помощью танца — это целый пласт культуры и народного сознания.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=la1NP-rCo3Q

Текст: Анна Юдина

Хоровод — основной элемент многих славянских праздников. Хороводы водились для гармонизации человеческих энергий, чтобы не терять ощущения целостности со своими сородичами и единения с Природой. Хоровод распространён в основном у славян, но встречается /под разными названиями/ и у других народов. Названия танца у разных славянских народов: коло (сербское), оро (македонское), коло (хорватское), хоро (болгарское). Название у других народов: ёхор (бурятское), хорэ (молдавское), хейро (эвенское), хоруми (грузинское) и др. Определённое сходство с Хороводом также имеют танцы лонгдол и менуэт. Хоровод – это не просто незамысловатая забава, это – Танец Жизни, состоящий из символов вселенского лада. Каждый его участник, способен как познать принципы Мироздания, так и распутать спутанные петли своей жизни. Таким образом – Хоровод является мощной и вместе с тем уникальной психотехникой, бережно передаваемой из глубины веков.

Наши Предки хороводили в лугах и полях, на берегу рек и озёр; участники, взявшись за руки, плавно, в медленном темпе двигались по кругу (рядами, парами, извивающейся цепочкой и др.) иногда выстраивались в линии друг против друга, иногда темп движения убыстряли…

Все Хороводы привязаны к временам года, каждый сезон встречает свой Хоровод. Есть летние купальские, есть пробуждающая землю «Веснянка» — эти Хороводы нельзя водить зимой: природа может отреагировать, и снег растает. Существуют игровые Хороводы для парней и девушек, чтобы они почувствовали друг друга, влюбились. А есть — только для девушек. Одни из самых сложных — Хороводы объединения родов на венчании. Тут главное, какой бы быстрый ритм ни задавался, не разорвать рук. Это важно, чтобы почувствовать единство родов. Такие мероприятия гармонизируют отношения между новыми родственниками, позволяют наладить контакт.

Хороводами передавали Родовую мудрость.

Хороводами целили больных. Танцоры кружились вокруг больного, создавая вокруг него огромный по силе энергетический вихрь и передавали ему необходимую для выздоровления энергию. Терапевтический эффект Хороводов сложно переоценить, скорее можно недооценить.

Происхождение названия

Хоровод — хором водить

Ещё одна версия говорит о том, что слово «Хоровод» следует писать через буквы «А», получаем «Харавод», где Ха — положительная энергия, Ра — изначальный свет, Вод — водить.

Что такое Хоровод и в чём его сакральный смысл?

Хороводы – одно из древнейших обрядовых действий, связанных с культом Солнца.

В жизнь людей Хороводы пришли из глубины веков. По мнению археологов, они известны людям уже с эпохи палеолита. Хороводы отражают стремление людей к созданию единого гармоничного узора жизни, неразрывную связь поколений, взаимодействие с пространством и движущихся внутри него потоков Жизни.

Большое символическое значение имеет форма круга, она воплощает в себе временной цикл, божественное начало и вечный круговорот всего сущего: Хоровод планет вокруг Солнца, который в свою очередь, находит отражение в кругоподобных планах храмов. Круг у многих народов считался универсальным символом непрекращающегося бытия и вечности.

Хоровод планет Солнечной системы располагается вблизи плоскости, проходящей через солнечный экватор, и кружит вокруг Солнца в одном и том же направлении. Горит солнечный костёр, а вокруг него Хоровод планет.

Иногда планеты выстраиваются в ряд.

Традиционный Хоровод состоит из шести фигур, в строгой последовательности переходящих одна в другую, причём каждая из них выполняется под определённую песню, имеет своё имя и выполняется в определенном ритме.

Начавшись неторопливо, от фигуры к фигуре, от действия к действию, темп Хоровода постепенно наращивается, убыстряется ритм. Этот обряд образно отображает древнейшие, восходящие к первичной арийской мифологии, представления славян о рождении Вселенной и Сотворении Мира.

Этот изначальный, объединяющий, сакральный обряд, лежащий в основе всех древних мистерий, пробуждает подсознание участвующих, вызывая тем самым глубинное переживание единства космоса и всех его частей, находящихся в полной гармонии и взаимосвязи.

Все участвующие в Хороводе, выходят духовно окрепшими и просветленными, с чувством осознания того, что не передать никакими словами или их письменным выражением.

Хоровод – сакральное священное действие, пожалуй, самое древнее на земле. Это вид народного творчества, значит, создавались Хороводы коллективно. Именно поэтому они несут в себе глубины коллективного безсознательного, являются выражением подсознательного каждого человека, складываясь в общую картину мироустройства, здоровых гармоничных матриц взаимодействия, общих для всех людей, всех народов, во все времена.

Хороводы архаичны сами по себе, содержат глубокие смыслы и мудрость не одного поколения, поэтому и сохранились они по сей день в своей первозданной чистоте.

В Хороводах гармонично сочетаются: музыка, песня, танец, слова, ритм, темп.

Поэтому «водя круги» внутренний космос каждого человека приходит до ладу, всё вокруг умиротворяется, гармонизируется, во внутреннем мире человека подсознательно выстраивается модель гармоничного, творческого, приносящего щедрые плоды взаимодействия в социуме и в парных мужско-женских отношениях.

Хороводы невозможно водить одному или «самому по себе», поэтому личность каждого научается самобытно проявляться, не нарушая границы других людей, не вразрез с природным жизненным укладом, с почтением и уважением к миру каждого человека, совместно водящего Хороводы.

Во время вождения Хороводов люди научаются слышать и чувствовать друг друга, действовать слажено, ценить отличия функций мужчины и женщины.

В Хороводах юноши и девушки всегда выполняли разные функции, при нарушении которых Хоровод просто не мог состояться, разваливался.

Юноши – задавали ритм и темп Хоровода, выстраивали его структуру. Важно было делать это так, чтобы девушке легко было следовать за этой структурой, легко петь и песня не прерывалась, лилась как реченька.

В Хороводах всегда был смотрящий – обычно старейшина, уважаемый мужчина в почтенном возрасте, который следил за тем, чтобы юноши не сбивали ритм и темп Хоровода.

Так юноши, шутя и играючи, научались заботливо и бережно относиться к девушкам, вести за собой так, чтобы «хотелось следовать за ними», приобретали подсознательное знание о том, что счастье девушек зависит от них, от их действий, осваивали свою главенствующую роль в отношениях.

У девушек была другая функция в Хороводах. Они должны были следовать за юношей, плавно, непрерывно, красиво петь песню и двигаться. Так они научались умиротворять, приводить до ладу всё вокруг, наполнять пространство любовью, красотой, нежностью. Так девушки подсознательно научались создавать пространство, в котором хочется быть, в котором наполняешься энергией, отдыхаешь душой и телом.

Водя такие Хороводы, юноши и девушки программировали свою жизнь быть такой же плавной, спокойной, текучей, умиротворённой, стабильной, лёгкой, весёлой и красивой, как сам Хоровод.

У Хоровода всегда были водящие. Это обычно самые активные юноши и девушки. Простой Хоровод могла вести и одна девушка, а вот сложные, парные Хороводы с мужской и женской отдельной линией обязательно водили два водящих – юноша и девушка. Вести Хоровод – это большая ответственность, ведь водящий задаёт тон, темп и стиль Хороводу. Он всё время должен думать о том, чтобы в этом Хороводе никто не устал, чтобы всем было легко и приятно, чтобы Хоровод складывался в гармоничную структуру и был безпрерывным. И при этом ещё чтобы и сам водящий получал удовольствие от вождения. Если Хоровод ведётся правильно, то у всех участников выравнивается сердцебиение и дыхание. И тогда можно водиться до самого утра без усталости и переутомлений.

Хороводы невозможно водить не со-настроившись друг с другом, не научившись понимать ход мысли друг друга, не чувствуя друг друга и не умея мгновенно реагировать на изменения ситуации и настроений.

Все водящие Хоровод становятся единым целым, сохраняя свою уникальность, которая влияет на ход Хоровода, совместно с другими уникальностями создаёт единый целостный гармоничный мир Хороводов.

Не удивительно, что научившись водить Хороводы, юноши и девушки быстро создавали пары и быстро женились. Гармоничная структура взаимодействия настолько пропитывала каждую клетку водящего Хоровод, так гармонично складывалась в структуру личности человека, что после свадьбы потребность водить Хоровод обычно отпадала. В Хороводах оставались только свободные юноши и девушки, а замужние и женатые лишь изредка, ради удовольствия и развлечения, обычно только на праздники приходили похороводиться.

В старину говорили – пошли круги водить.

Людям, водящим Хоровод, становится легче принять цикличность жизни, вечность происходящего, несмотря на «смену формы», появляется более масштабный взгляд на жизнь: всё проходит и возвращается, всё было, есть и будет, даже Я.

Конечно же, с такой позиции намного проще смотреть на жизнь, намного легче решать актуальные жизненные задачи, чаще принимать мудрые и взвешенные решения, видеть и понимать истинные причинно-следственные связи событий.

Источник — http://drevoroda.ru/interesting/articles/700/2273.html

При составлении статьи использованы материалы сайтов:

http://www.liveinternet.ru/users/dara3/post226032602/

http://festivalirusi.ru/xorovod-vodit-zdorovym-byt/

http://drevo-jizni-ru.livejournal.com/2152.html

Более подробно и глубоко о Хороводах, их сакральном смысле и практическом применении для изменения и гармонизации жизни смотрите в этих видео: