День пряничного домика — 12 декабря! Независимо от того, являетесь ли вы экспертом по изготовлению печенья или ваш испеченный дом разваливается, как только вы приклеиваете третью стену глазурью, мы все можем согласиться с тем, что лучшая часть строительства пряничного домика — это съесть сладкое удовольствие! День пряничного домика — история праздника, как отмечать День пряничного домика, узнайте в следующей статье на kakogo-chisla.ru.

Содержание

- Какого числа День пряничного домика

- История Дня пряничного домика

- Почему важен День пряничного домика

- Как отметить День пряничного домика

- Интересные факты о пряничных домиках

Какого числа День пряничного домика

Какого числа отмечают День пряничного домика? Узнайте, на какой день выпадает День пряничного домика в 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025 и 2026 годах.

| Год | Дата | День |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 12 декабря | Понедельник |

| 2023 | 12 декабря | Вторник |

| 2024 | 12 декабря | Четверг |

| 2025 | 12 декабря | Пятница |

| 2026 | 12 декабря | Суббота |

История Дня пряничного домика

Ничто так не приближает праздник, как запах свежеиспеченных имбирных пряников. Но до того, как декоративное печенье возглавило конкурс популярности на праздничном десертном столе, выпечка пряников была специфической профессией. В 17 веке имбирные пряники разрешалось делать только профессиональным пекарям, за исключением Рождества и Пасхи, когда их мог печь кто угодно.

В Европе имбирные пряники продавались в специальных магазинах и на сезонных рынках, где продавались сладости и имбирные пряники в форме сердец, звезд, солдатиков, младенцев, труб, мечей, пистолетов и животных. Имбирные пряники особенно продавались вне церквей по воскресеньям. Религиозные пряничные барельефы приобретались для определенных религиозных событий, таких как Рождество и Великий пост. Украшенные имбирные пряники дарили взрослым и детям или в знак любви покупали специально к свадьбе.

Пряники также считались формой популярного искусства в Европе. Формы часто отображали реальные события, изображая новых правителей, их детей, супругов и партии. Значительные коллекции плесени хранятся в Этнографическом музее в Торуни, Польша, и в Музее хлеба в Ульме, Германия.

По мнению некоторых историков кулинарии, традиция изготовления пряничных домиков зародилась в Германии в начале 1800-х годов. Первые пряничные домики стали результатом известной сказки братьев Гримм «Гензель и Гретель». После того, как эта история была опубликована, немецкие пекари начали выпекать сказочные домики из имбирных пряников. Они были привезены в Америку немецкими иммигрантами и стали популярны во время рождественского сезона.

Почему важен День пряничного домика

- Имеет сказочное происхождение

Люди в Европе ели имбирные пряники на протяжении веков, но мы можем поблагодарить братьев Гримм за популярность пряничных домиков. «Гензель и Гретель» были опубликованы в 19 веке — помните это? Это сказка, в которой ведьма заманивает брата и сестру в плен в свой дом, сделанный из имбирных пряников и конфет, а затем пытается откормить их, чтобы съесть (спойлер: они убегают!) Эта история стала очень популярной в Германии. и в результате люди начали печь пряничные домики во время праздников.

- Это выявляет вашего внутреннего ребенка

Нет ничего лучше старомодного декоративно-прикладного искусства, чтобы вы снова почувствовали себя ребенком. И это еще более верно, когда материалы для вашего крафта а) съедобны и б) битком набиты сахаром. Добавьте к этому детское волнение, которое возникает у людей всех возрастов во время праздников.

- Плюс: имбирь полезен, верно?

Основной вкус имбирных пряников — имбирь. Это то, что придает имбирным пряникам теплый праздничный вкус и легкую пикантность. Имбирь также имеет целый ряд преимуществ для здоровья: он может помочь при расстройстве желудка или тошноте, обладает противовоспалительным действием и может даже снизить уровень холестерина, снизить факторы риска сердечных заболеваний и обладает некоторыми противораковыми свойствами.

Советуем почитать: День сладкой ваты

Как отметить День пряничного домика

- Испечь пряничный домик с нуля

Пряничное тесто на удивление легко приготовить. Возможно, вам придется сбегать в магазин за специями (молотый имбирь, корица и гвоздика) и патокой (еще один ключевой ингредиент), но мы готовы поспорить, что почти все остальное уже есть в вашей кладовой. Самое сложное — правильно отмерить стены и крышу пряничного домика, прежде чем их испечь. Если у вас есть лишнее тесто, почему бы не сделать к нему несколько имбирных человечков и бабочек?

- Устройте конкурс пряничных домиков

Испеките или купите кучу кусочков пряничного домика, белую глазурь и тонны разноцветных конфет. Пригласите друзей, включите праздничные мелодии и посмотрите, кто сможет сделать самый красиво украшенный пряничный домик!

- Запейте его имбирным латте

В декабре эти напитки появляются в меню кофеен по всей стране. Но если вы не можете найти его рядом с вами, его легко приготовить. Либо купите имбирный сироп, либо приготовьте его самостоятельно, кипятя на плите воду, сахар, молотый имбирь, корицу и душистый перец, пока он не уварится и не загустеет. Смешайте сироп с порцией эспрессо и залейте теплым молоком. Таким образом, у вас есть праздничное настроение в кружке, бариста не требуется.

Интересные факты о пряничных домиках

- Шрек представляет Джинджи

Пряничный человечек Джинджи стал любимцем фанатов из «Шрека» 2001 года.

- 2009 г. Самый большой в мире пряничный человечек

Самый большой пряничный человечек весил 650 кг и был сделан IKEA Furuset в Осло, Норвегия.

- 2013 г. Самый большой в мире пряничный домик

Имбирный пряничный домик высотой 650 см в Брайане, штат Техас, содержит 35,8 миллиона калорий и занимает площадь 2520 квадратных футов (почти размер теннисного корта). Книга рекордов Гиннеса объявила его самым большим из когда-либо существовавших.

Советуем почитать: День печенья

День пряничного домика — повод полакомиться вкусным и красивым рождественским угощением!

Post Views: 151

Пряничный домик — символ Рождества и новогоднего настроения

У новогодней поры много символов. Один из них — пряничный домик, пришедший к нам вместе со сказками братьев Гримм.

Давным-давно…

История приписывает традиции пряничных домиков довольно странную судьбу. Есть у широко известных и горячо любимых писателей братьев Гримм (Brüder Grimm) сказка «Гензель и Гретель», в которой брат и сестра попадают в лапы ведьме, живущей в лесу в пряничном домике. В 1912 году прямо под Рождество в Германии вышла в свет книга сказок братьев Гримм, которая включала в себя и эту сказку. Говорят, именно с тех пор пряничные домики появились на рождественских столах.

От мала до велика

Создание пряничного домика — это настоящая творческая история. Если вы пока не уверены в своих кулинарных талантах, начните с мини-шалашиков.

А освоив рецепт, возможно, поймете, что вам по плечу целый пряничный город.

Нужно иметь под рукой

Для приготовления домика понадобятся следующие ингредиенты:

- пшеничная мука — 1,5 килограмма;

- сахар — 550 г сахара;

- вода — 1 стакан;

- сливочное масло — 150 граммов;

- мед — 450 граммов;

- яйца — 5 штук;

- сода — 1 чайная ложка;

- соль — щепотка;

- корица — 2 чайные ложки;

- сахарная пудра — 500 граммов;

- карамельные украшения (конфеты, леденцы).

Готовить просто

200 граммов сахара высыпать в кастрюлю и, помешивая, аккуратно растопить. Влить 1 стакан кипящей воды, высыпать еще 200 граммов сахара, проварить около 5 минут.

Сваренную карамель перелить в емкость, где будет замешиваться тесто. Добавить масло и мед. Все перемешать.

Добавить корицу и 1 стакан муки, перемешать, дать немного остыть.

Разбить в тесто 3 яйца, перемешать. Добавлять понемногу муку, постоянно замешивая тесто.

После того, как тесто уже будет трудно перемешивать в посуде, выложить его на стол и вымесить. Готовое тесто нужно обмотать пленкой и на несколько часов поместить в холодильник.

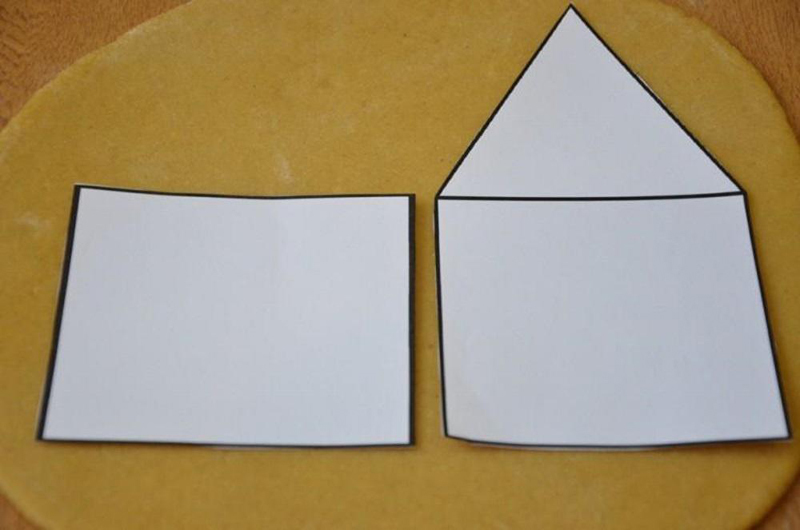

Далее тесто нужно раскатать толщиной примерно в полсантиметра и вырезать из него детали домика, воспользовавшись заранее нарисованными и вырезанными из бумаги шаблонами. Если вы готовите подобное блюдо впервые, лучше воздержаться от сложных форм и вырезания окон и дверей. Их можно будет потом просто нарисовать глазурью.

Запекаются детали домика 10-15 минут.

Пока детали остывают, нужно приготовить глазурь для украшения. Для этого взбиваются 2 яичных белка вместе с сахарной пудрой. В конце можно добавить немного лимонного сока.

Украшать домик удобнее, пока он еще не собран. Перелейте глазурь в кондитерский мешок или шприц и дайте волю фантазии.

Для сборки деталей можно воспользоваться глазурью, обильно смазав ею края частей. Но более надежное сцепление обеспечивает карамель. Для ее приготовления просто растопит

Это может Вам понравиться:

Необычный праздник — День пряничного домика, отмечается ежегодно 12 декабря. Строительство пряничных домиков — это прекрасный способ провести время с семьей или друзьями. Но как появилась идея строить избушки из пряников, и кто это придумал?

Историки утверждают, что имбирь добавляют в продукты питания с древних времен. Считается, что первый имбирный пряник испекли в Европе в конце 11 века. Имбирь обладает не только интересным вкусом, но и полезными свойствами, которые помогают сохранять выпечку. Согласно французской легенде, пряники были привезены в Европу в 992 году нашей эры армянским монахом. Пряники в форме человечков появились уже в 16 веке.

Во многих европейских странах профессия пекарей стала признанной, а в 17 веке пряники разрешили печь на любые праздники, кроме Рождества и Пасхи. В Европе пряники в форме сердец, звезд, солдатов, труб, мечей, пистолетов и животных продавались в специальных магазинах и на сезонных рынках.

Традиция изготовления украшенных пряничных домиков началась в Германии в начале 1800-х годов. По словам некоторых исследователей, первые пряничные домики появились благодаря знаменитой сказке братьев Гримм про Гензель и Гретель. С тех пор традиция строить пряничные домики прижилась и до сих пор практикуется во многих странах.

Чтобы отпраздновать День пряничного домика, сходите всей семьей в магазин за продуктами для имбирного теста, а дома приступите к выпечке и формированию своего домика. К тому же, сейчас в магазинах можно найти уже готовые наборы для формирования не только домиков, но и пряничных поездов, елочек и прочих строений. А вы в этом году будете праздновать День пряничного домика?

Способ приготовления пряничного домика

Домик обычно состоит из нескольких коржей — четырех «стен» и «крыши». Изготовленные коржи смазывают яйцом, выпекают и охлаждают. Затем из этих «деталей», скрепляя их между собой спичками или зубочистками, или склеивая густым сахарным сиропом, собирают домик. «Стыки» между коржами снаружи покрывают сахарной или шоколадной глазурью.

Пряничный домик нередко украшают различными декоративными элементами: это могут быть фигурки зверей, деревья, цветочки и сердечки, а также роспись из крема. Большинство элементов домика, в том числе и украшения, изготавливаются из пряничного теста и покрываются глазурью различных цветов.

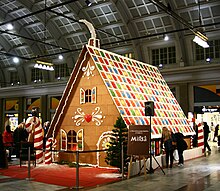

Существует множество разновидностей пряничных домиков. Это могут быть как обычные маленькие, так и целые замки и особняки. Также с использованием пряничного теста изготавливают уменьшенные копии известных сооружений: например, лондонский Биг-Бен и Эмпайр-Стейт Билдинг в Нью-Йорке.

Сказка братьев Гримм «Гензель и Гретель»

Это история о юных брате и сестре, которым угрожает ведьма-людоедка, живущая глубоко в лесу, в доме, построенном из хлеба и сладостей. Эти дети, попав к ведьме, спасают свои жизни благодаря находчивости.

Под угрозой голода отец двух детей, мальчика и девочки, поддается уговорам второй жены избавиться от детей и заводит их в лес. Дети же, подслушав разговор родителей, принимают необходимые меры к своему спасению. Первый раз Гензель бросает на дорогу камешки, которых загодя набрал полные карманы. По этой примете дети возвращаются домой. Второй раз набрать камешки не удается из-за коварства мачехи, и Гензель бросает на дорогу хлебные крошки, которые склевывают лесные птицы.

Заблудившись в чаще, Гензель и Гретель идут вслед за белоснежной птичкой и набредают на пряничный дом из хлеба, с крышей из пряников и окнами из сахара, где попадаются в ловушку ведьмы, которая ест детей. Брата ведьма сажает в клетку, а сестра под угрозами старухи в течение четырех недель откармливает его на съедение.

Гензель обманывает подслеповатую ведьму с помощью косточки, выдавая ее за свой худосочный палец. Не в силах более терпеть, злодейка хочет живьем зажарить Гретель, но девочка, проявив находчивость, убивает ведьму, заперев ее в духовке печи.

Обобрав дом мертвой, сожженной дотла ведьмы, дети пытаются добраться до дома отца. Переплыть широкую реку им помогает уточка, а дальше они узнают дорогу по лесным приметам. За время их отсутствия мачеха умерла по неизвестным причинам. А украденных в доме ведьмы драгоценностей хватает на дальнейшую жизнь в достатке.

Такая выпечка очень популярна, на неё всегда пред Рождеством есть спрос. А дело в том, что от этих сказочных, необычных и сладких домиков веет волшебством и беззаботным детством.

«Предки» пряничных домиков

Подойдя к избушке поближе, они увидели, что она вся из хлеба построена и печеньем покрыта, да окошки-то у нее были из чистого сахара. «Вот мы за нее и примемся, — сказал Гензель, — и покушаем. Я вот съем кусок крыши, а ты, Гретель, можешь себе от окошка кусок отломить — оно, небось, сладкое». Вытянулся Гензель во весь рост и отломил кусочек крыши, чтобы попробовать, какая она на вкус, а Гретель стала лакомиться окошками. («Гензель и Гретель», сборник немецких народных сказок братьев Гримм «Детские и семейные сказки», 1812 год)

На самом деле, традиция печь съедобные домики и прочие жилища не была «запатентована» братьями Гримм. Возможно, идею своего знаменитого сладкого, завлекающего заблудившихся детей обиталища злой ведьмы они «подсмотрели» у древних римлян. Те действительно пекли из сдобного, вкусного теста домики, чтобы в них якобы селились боги. Так римляне создавали свой домашний, комнатный пантеон. После того как боги пожили в таком съедобном жилище (которое, к слову, ставилось в домашний алтарь), оно с удовольствием съедалось домочадцами.

Современные традиции

Конечно, подобные языческие поверья и обычаи с приходом в европейские страны христианства уже не актуальны. Чего не скажешь о популярности пряничных домиков, которая с XIX века только начала набирать обороты.

Сегодня к каждым зимним праздникам для праздничного стола готовят рождественскую выпечку в форме всевозможных жилищ, будь то шалаши, домики, избушки или даже дворцы. Производят их и массово, в фабричных условиях (к слову, некоторые производители выпускают оригинальные наборы «Сделай сам» со всем необходимым и подробной инструкцией, как приготовить и «построить» домик из пряничного теста).

Но наиболее красивые, оригинальные и вкусные пряничные домики делаются вручную. Ежегодно происходит негласное всемирное соревнование «Кто сделает самым впечатляющий рождественский пряничный домик?». Помимо этого, организуются и локальные выставки-продажи, фестивали, участники которых (как профи, так и любители) выставляют на всеобщее обозрение творения своих рук — пряничные домики ручной работы. Подобного рода конкурсы до сих пор пользуются спросом в европейских странах, в Америке и, конечно, у наших умельцев.

Всеобщая любовь

Не требует особого пояснения тот факт, что дети просто обожают пряничные домики. Ещё бы, они не только красивые, но, вдобавок, очень вкусные. «Строительные материалы» для этих праздничных лакомств самые подходящие:

- пряничное медовое тесто, которое не черствеет, не портится намного дольше другого, оставаясь свежим и вкусным;

- сахарная глазурь, использующаяся как в качестве украшения, так и в роли «цемента» для склейки домика;

- прочие многочисленные сладкие ингредиенты, выполняющие в основном роль украшения (орешки, цукаты, карамель, марципан, шоколад, мастика, засахаренные фрукты и т. д.).

Какой же ребенок откажется от такого многообразия сладких вкусов, к тому же, оформленных столь необычно и сказочно?

Хотя, как бы взрослые не увиливали и не отрицали свою любовь к сладенькому, получить к рождественскому или новогоднему столу такой съедобный шедевр (а ещё и сделанный вручную) приятно будет каждому. Сделать пряничный домик не так уж и сложно:

- замесить тесто (рецептов в Сети немало);

- сделать (или опять же взять из Сети) чертеж домика;

- вырезать детали и запечь их;

- приготовить глазурь или другой съедобный клей;

- собрать и высушить домик;

- украсить в соответствии со своими предпочтениями и фантазией.

Да, процесс этот хлопотный, но такое самостоятельное, а может, и семейное «строительство» пряничных домиков принесет не меньше радости и предвкушения чуда, чем сам результат. А готовый пряничный домик гарантированно добавит дому ощущение уюта и семейного праздника.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A typical store-bought gingerbread house

A gingerbread house is a novelty confectionery shaped like a building that is made of cookie dough, cut and baked into appropriate components like walls and roofing. The usual base material is crisp gingerbread, hence the name. Another type of model-making with gingerbread uses a boiled dough that can be moulded like clay to form edible statuettes or other decorations. These houses, covered with a variety of candies and icing, are popular Christmas decorations.

History[edit]

Painting depicting gingerbread sold at the fair

Records of honey cakes can be traced to ancient Rome.[1] Food historians ratify that ginger has been seasoning foodstuffs and drinks since antiquity. It is believed gingerbread was first baked in Europe at the end of the 11th century, when returning crusaders brought back the custom of spicy bread from the Middle East.[2] Ginger was not only tasty, it had properties that helped preserve the bread.

According to the French legend, gingerbread was brought to Europe in 992 by the Armenian monk, later saint, Gregory of Nicopolis (Gregory Makar). He lived for seven years in Bondaroy, France, near the town of Pithiviers, where he taught gingerbread cooking to priests and other Christians. He died in 999.[3][4][5] An early medieval Christian legend elaborates on the Gospel of Matthew’s account of the birth of Jesus. According to the legend, attested to in a Greek document from the 8th century, of presumed Irish origin and translated into Latin with the title Collectanea et Flores, in addition to gold, frankincense, and myrrh, given as gifts by three «wise men from the east» (magi), ginger was the gift of one wise man (magus) who was unable to complete the journey to Bethlehem. As he was lingering in his last days in a city in Syria, the magus gave his chest of ginger roots to the Rabbi who had kindly cared for him in his illness. The Rabbi told him of the prophesies of the great King who was to come to the Jews, one of which was that He would be born in Bethlehem, which, in Hebrew, meant «House of Bread». The Rabbi was accustomed to having his young students make houses of bread to eat over time to nourish the hope for their Messiah. The Magus suggested adding ground-up ginger to the bread for zest and flavor.[citation needed] Gingerbread, as we know it today, descends from Medieval European culinary traditions. Gingerbread was also shaped into different forms by monks in Franconia, Germany in the 13th century. Lebkuchen bakers are recorded as early as 1296 in Ulm and 1395 in Nuremberg, Germany. Nuremberg was recognized as the «Gingerbread Capital of the World» when in the 1600s the guild started to employ master bakers and skilled workers to create complicated works of art from gingerbread.[2] Medieval bakers used carved boards to create elaborate designs. During the 13th century, the custom spread across Europe. It was taken to Sweden in the 13th century by German immigrants; there are references from Vadstena Abbey of Swedish nuns baking gingerbread to ease indigestion in 1444.[6][7] The traditional sweetener is honey, used by the guild in Nuremberg. Spices used are ginger, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg and cardamom.

Gingerbread figurines date back to the 15th century, and figural biscuit-making was practised in the 16th century.[8] The first documented instance of figure-shaped gingerbread biscuits is from the court of Elizabeth I of England: she had gingerbread figures made in the likeness of some of her important guests.[9]

History of gingerbread shaping[edit]

Decorated gingerbread hearts with mirrors, hussars, and market souvenirs in Croatia

A gingerbread print horse

The gingerbread bakers were gathered into professional baker guilds. In many European countries gingerbread bakers were a distinct component of the bakers’ guild. Gingerbread baking developed into an acknowledged profession. In the 17th century only professional gingerbread bakers were permitted to bake gingerbread except at Christmas and Easter, when anyone was allowed to bake it.[2]

In Europe gingerbreads were sold in special shops and at seasonal markets that sold sweets and gingerbread shaped as hearts, stars, soldiers, babies, riders, trumpets, swords, pistols and animals.[1] Gingerbread was especially sold outside churches on Sundays. Religious gingerbread reliefs were purchased for the particular religious events, such as Christmas and Easter. The decorated gingerbreads were given as presents to adults and children, or given as a love token, and bought particularly for weddings, where gingerbreads were distributed to the wedding guests.[1] A gingerbread relief of the patron saint was frequently given as a gift on a person’s name day, the day of the saint associated with his or her given name.[1] It was the custom to bake biscuits and paint them as window decorations. The most intricate gingerbreads were also embellished with iced patterns, often using colours, and also gilded with gold leaf.[10] Gingerbread was also worn as a talisman in battle or as protection against evil spirits.[4]

Gingerbread was a significant form of popular art in Europe;[1] major centers of gingerbread mould carvings included Lyon, Nuremberg, Pest, Prague, Pardubice, Pulsnitz, Ulm, and Toruń. Gingerbread moulds often displayed actual happenings, by portraying new rulers and their consorts, for example. Substantial mould collections are held at the Ethnographic Museum in Toruń, Poland and the Bread Museum in Ulm, Germany. During the winter months medieval gingerbread pastries, usually dipped in wine or other alcoholic beverages, were consumed. In America, the German-speaking communities of Pennsylvania and Maryland continued this tradition until the early 20th century.[1] The tradition survived in colonial North America, where the pastries were baked as ginger snap cookies and gained favour as Christmas tree decorations.[1]

The tradition of making decorated gingerbread houses started in Germany in the early 1800s. According to certain researchers, the first gingerbread houses were the result of the well-known Grimm’s fairy tale «Hansel and Gretel»[2] in which the two children abandoned in the forest found an edible house made of bread with sugar decorations. After this book was published, German bakers began baking ornamented fairy-tale houses of lebkuchen (gingerbread). These became popular during Christmas, a tradition that came to America with Pennsylvanian German immigrants.[11] According to other food historians, the Grimm brothers were speaking about something that already existed.[2]

Modern times[edit]

Replica of the White House made of gingerbread and white chocolate

Swedish gingerbread house being prepared. Glaze is put on the walls.

In modern times the tradition has continued in certain places in Europe. In Germany, Christmas markets sell decorated gingerbread before Christmas. (Lebkuchenhaus or Pfefferkuchenhaus are the German terms for a gingerbread house.) Making gingerbread houses is a Christmas tradition in many families. They are typically made before Christmas using pieces of baked gingerbread dough assembled with melted sugar. The roof ’tiles’ can consist of frosting or candy. The gingerbread house yard is usually decorated with icing to represent snow.[12]

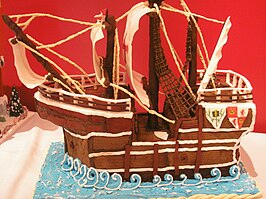

A gingerbread house does not have to be an actual house, although it is the most common. It can be anything from a castle to a small cabin, or another kind of building, such as a church, an art museum,[13] or a sports stadium,[14] and other items, such as cars, gingerbread men and gingerbread women, can be made of gingerbread dough.[15]

In most cases, royal icing is used as an adhesive to secure the main parts of the house, as it can be made quickly and forms a secure bond when set.

In Sweden gingerbread houses are prepared on Saint Lucy’s Day.[citation needed] Since 1991, the people of Bergen, Norway, have built a city of gingerbread houses each year before Christmas. Named Pepperkakebyen (Norwegian for «the gingerbread village»), it is claimed to be the world’s largest such city.[16] Every child under the age of 12 can make their own house at no cost with the help of their parents. In 2009, the gingerbread city was destroyed in an act of vandalism.[17] A group of building design, construction, and sales professionals in Washington, D.C., also collaborate on a themed «Gingertown» every year.[14]

In San Francisco, the Fairmont and St. Francis hotels display rival gingerbread houses during the Christmas season.[18]

Guinness World records[edit]

A full-scale gingerbread house as a Christmas decoration in Stockholm, 2009 (It was made of 294 kg (648 lb) flour, 92 kg (203 lb) margarine, 100.4 kg (221 lb) sugar, 66.3 L (14.6 imp gal; 17.5 US gal) Golden syrup, 2.2 kg (4.9 lb) each of cinnamon, cloves, ginger and 3.7 kg (8.2 lb) baking powder.[19])

In 2013, a group in Bryan, Texas, USA, broke the Guinness World Record set the previous year for the largest gingerbread house, with a 2,520-square-foot (234 m2) edible-walled house in aid of a hospital trauma centre.[20] The gingerbread house had an estimated calorific value exceeding 35.8 million and ingredients included 2,925 pounds (1,327 kg) of brown sugar, 1,800 pounds (820 kg) of butter, 7,200 eggs and 7,200 pounds (3,300 kg) of general purpose flour.[20]

The executive sous-chef at the New York Marriott Marquis hotel, Jon Lovitch, broke the record for the largest gingerbread village with 135 residential and 22 commercial buildings, and cable cars and a train also made of gingerbread.[21] It was displayed at the New York Hall of Science. Another contender from Bergen, Norway made a gingerbread town called Pepperkakebyen.[22]

Gallery[edit]

- Gingerbread houses

-

Gingerbread house with candy

-

A gingerbread house with clock and candy decorations

-

Gingerbread house with double doors

-

Gingerbread house with steps and trees

-

Gingerbread house with path

-

Gingerbread house with lighting

-

Gingerbread house with snowman

-

Gingerbread ship

-

Gingerbread house as a Christmas Eve decoration

-

Gingerbread village with model trains

-

Gingerbread house and Elizabeth Tower in London, United Kingdom

See also[edit]

| External video |

|---|

- Gingerbread man

- Lebkuchen

- Aachener Printen

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g «Gingerbread». enotes.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Olver, Lynne. «Traditional Christmas foods» (PDF). The Food Timeline. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013 – via City of Tea Tree Gully.

- ^ La Confrérie du Pain d’Epices, archived from the original on 15 December 2013, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ^ a b Le Pithiviers, archived from the original on 12 December 2013, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ^ Monastère orthodoxe des Saints Grégoire Armeanul et Martin le Seul, archived from the original on 10 January 2014, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ^ «History and tradition». Annas Pepparkakor. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ «Pepparkakan och dess historia». Danska Wienerbageriet. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Campbell Franklin, Linda (1997). 300 Years of Kitchen Collectibles (4th ed.). Iowa, Wisconsin: Krause. p. 183. ISBN 9780896891128.

- ^ «A History of Gingerbread Men». Ferguson Plarre Bakehouses. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- ^ «Gingerbread (more)». Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ «Holiday Tradition with Spicy History». Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 9 December 2001 (p. N-9).

- ^ Brones, Anna. «The Magic of Swedish Gingerbread Cookies». Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ «Gingerbread Architecture Makes Normal Gingerbread Houses Look Pathetic». Huffington Post. 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b Basch, Michelle (5 December 2013). «‘Gingertown’ brings modern twist to gingerbread houses». WTOP-FM.

- ^ «Gingerbread model houses COOP» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ «Pepperkakebyen i Bergen» (in Norwegian and English). Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Rolleiv Solholm (23 November 2009). «Bergen’s «Gingerbread City» vandalized». The Norway Post. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Rubenstein, Steve (3 December 2013). «The great San Francisco gingerbread war commences». San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ List and amount of ingredients used (sign at rear of gingerbread house). Stockholm. 2009.

- ^ a b Herskovitz, Jon (6 December 2013). «With nearly a ton of butter, Texas gingerbread house sets record». Texas A &M University / Reuters.

- ^ «Largest gingerbread village: Chef Jon Lovitch breaks Guinness World Records’ record». World Record Academy. 3 December 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Antonia (22 December 2018). «A brief history of the gingerbread house». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Weaver, William Woys – The Christmas Cook, Three Centuries of American Yuletide Sweets.

- Eliza Leslie Miss Leslie’s New Cookery Book – The Original Classic Edition Miss Leslie’s New Cookery Book, online

External links[edit]

- Gingerbread[permanent dead link] at the Open Directory Project

- Facebook Fan Page

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A typical store-bought gingerbread house

A gingerbread house is a novelty confectionery shaped like a building that is made of cookie dough, cut and baked into appropriate components like walls and roofing. The usual base material is crisp gingerbread, hence the name. Another type of model-making with gingerbread uses a boiled dough that can be moulded like clay to form edible statuettes or other decorations. These houses, covered with a variety of candies and icing, are popular Christmas decorations.

History[edit]

Painting depicting gingerbread sold at the fair

Records of honey cakes can be traced to ancient Rome.[1] Food historians ratify that ginger has been seasoning foodstuffs and drinks since antiquity. It is believed gingerbread was first baked in Europe at the end of the 11th century, when returning crusaders brought back the custom of spicy bread from the Middle East.[2] Ginger was not only tasty, it had properties that helped preserve the bread.

According to the French legend, gingerbread was brought to Europe in 992 by the Armenian monk, later saint, Gregory of Nicopolis (Gregory Makar). He lived for seven years in Bondaroy, France, near the town of Pithiviers, where he taught gingerbread cooking to priests and other Christians. He died in 999.[3][4][5] An early medieval Christian legend elaborates on the Gospel of Matthew’s account of the birth of Jesus. According to the legend, attested to in a Greek document from the 8th century, of presumed Irish origin and translated into Latin with the title Collectanea et Flores, in addition to gold, frankincense, and myrrh, given as gifts by three «wise men from the east» (magi), ginger was the gift of one wise man (magus) who was unable to complete the journey to Bethlehem. As he was lingering in his last days in a city in Syria, the magus gave his chest of ginger roots to the Rabbi who had kindly cared for him in his illness. The Rabbi told him of the prophesies of the great King who was to come to the Jews, one of which was that He would be born in Bethlehem, which, in Hebrew, meant «House of Bread». The Rabbi was accustomed to having his young students make houses of bread to eat over time to nourish the hope for their Messiah. The Magus suggested adding ground-up ginger to the bread for zest and flavor.[citation needed] Gingerbread, as we know it today, descends from Medieval European culinary traditions. Gingerbread was also shaped into different forms by monks in Franconia, Germany in the 13th century. Lebkuchen bakers are recorded as early as 1296 in Ulm and 1395 in Nuremberg, Germany. Nuremberg was recognized as the «Gingerbread Capital of the World» when in the 1600s the guild started to employ master bakers and skilled workers to create complicated works of art from gingerbread.[2] Medieval bakers used carved boards to create elaborate designs. During the 13th century, the custom spread across Europe. It was taken to Sweden in the 13th century by German immigrants; there are references from Vadstena Abbey of Swedish nuns baking gingerbread to ease indigestion in 1444.[6][7] The traditional sweetener is honey, used by the guild in Nuremberg. Spices used are ginger, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg and cardamom.

Gingerbread figurines date back to the 15th century, and figural biscuit-making was practised in the 16th century.[8] The first documented instance of figure-shaped gingerbread biscuits is from the court of Elizabeth I of England: she had gingerbread figures made in the likeness of some of her important guests.[9]

History of gingerbread shaping[edit]

Decorated gingerbread hearts with mirrors, hussars, and market souvenirs in Croatia

A gingerbread print horse

The gingerbread bakers were gathered into professional baker guilds. In many European countries gingerbread bakers were a distinct component of the bakers’ guild. Gingerbread baking developed into an acknowledged profession. In the 17th century only professional gingerbread bakers were permitted to bake gingerbread except at Christmas and Easter, when anyone was allowed to bake it.[2]

In Europe gingerbreads were sold in special shops and at seasonal markets that sold sweets and gingerbread shaped as hearts, stars, soldiers, babies, riders, trumpets, swords, pistols and animals.[1] Gingerbread was especially sold outside churches on Sundays. Religious gingerbread reliefs were purchased for the particular religious events, such as Christmas and Easter. The decorated gingerbreads were given as presents to adults and children, or given as a love token, and bought particularly for weddings, where gingerbreads were distributed to the wedding guests.[1] A gingerbread relief of the patron saint was frequently given as a gift on a person’s name day, the day of the saint associated with his or her given name.[1] It was the custom to bake biscuits and paint them as window decorations. The most intricate gingerbreads were also embellished with iced patterns, often using colours, and also gilded with gold leaf.[10] Gingerbread was also worn as a talisman in battle or as protection against evil spirits.[4]

Gingerbread was a significant form of popular art in Europe;[1] major centers of gingerbread mould carvings included Lyon, Nuremberg, Pest, Prague, Pardubice, Pulsnitz, Ulm, and Toruń. Gingerbread moulds often displayed actual happenings, by portraying new rulers and their consorts, for example. Substantial mould collections are held at the Ethnographic Museum in Toruń, Poland and the Bread Museum in Ulm, Germany. During the winter months medieval gingerbread pastries, usually dipped in wine or other alcoholic beverages, were consumed. In America, the German-speaking communities of Pennsylvania and Maryland continued this tradition until the early 20th century.[1] The tradition survived in colonial North America, where the pastries were baked as ginger snap cookies and gained favour as Christmas tree decorations.[1]

The tradition of making decorated gingerbread houses started in Germany in the early 1800s. According to certain researchers, the first gingerbread houses were the result of the well-known Grimm’s fairy tale «Hansel and Gretel»[2] in which the two children abandoned in the forest found an edible house made of bread with sugar decorations. After this book was published, German bakers began baking ornamented fairy-tale houses of lebkuchen (gingerbread). These became popular during Christmas, a tradition that came to America with Pennsylvanian German immigrants.[11] According to other food historians, the Grimm brothers were speaking about something that already existed.[2]

Modern times[edit]

Replica of the White House made of gingerbread and white chocolate

Swedish gingerbread house being prepared. Glaze is put on the walls.

In modern times the tradition has continued in certain places in Europe. In Germany, Christmas markets sell decorated gingerbread before Christmas. (Lebkuchenhaus or Pfefferkuchenhaus are the German terms for a gingerbread house.) Making gingerbread houses is a Christmas tradition in many families. They are typically made before Christmas using pieces of baked gingerbread dough assembled with melted sugar. The roof ’tiles’ can consist of frosting or candy. The gingerbread house yard is usually decorated with icing to represent snow.[12]

A gingerbread house does not have to be an actual house, although it is the most common. It can be anything from a castle to a small cabin, or another kind of building, such as a church, an art museum,[13] or a sports stadium,[14] and other items, such as cars, gingerbread men and gingerbread women, can be made of gingerbread dough.[15]

In most cases, royal icing is used as an adhesive to secure the main parts of the house, as it can be made quickly and forms a secure bond when set.

In Sweden gingerbread houses are prepared on Saint Lucy’s Day.[citation needed] Since 1991, the people of Bergen, Norway, have built a city of gingerbread houses each year before Christmas. Named Pepperkakebyen (Norwegian for «the gingerbread village»), it is claimed to be the world’s largest such city.[16] Every child under the age of 12 can make their own house at no cost with the help of their parents. In 2009, the gingerbread city was destroyed in an act of vandalism.[17] A group of building design, construction, and sales professionals in Washington, D.C., also collaborate on a themed «Gingertown» every year.[14]

In San Francisco, the Fairmont and St. Francis hotels display rival gingerbread houses during the Christmas season.[18]

Guinness World records[edit]

A full-scale gingerbread house as a Christmas decoration in Stockholm, 2009 (It was made of 294 kg (648 lb) flour, 92 kg (203 lb) margarine, 100.4 kg (221 lb) sugar, 66.3 L (14.6 imp gal; 17.5 US gal) Golden syrup, 2.2 kg (4.9 lb) each of cinnamon, cloves, ginger and 3.7 kg (8.2 lb) baking powder.[19])

In 2013, a group in Bryan, Texas, USA, broke the Guinness World Record set the previous year for the largest gingerbread house, with a 2,520-square-foot (234 m2) edible-walled house in aid of a hospital trauma centre.[20] The gingerbread house had an estimated calorific value exceeding 35.8 million and ingredients included 2,925 pounds (1,327 kg) of brown sugar, 1,800 pounds (820 kg) of butter, 7,200 eggs and 7,200 pounds (3,300 kg) of general purpose flour.[20]

The executive sous-chef at the New York Marriott Marquis hotel, Jon Lovitch, broke the record for the largest gingerbread village with 135 residential and 22 commercial buildings, and cable cars and a train also made of gingerbread.[21] It was displayed at the New York Hall of Science. Another contender from Bergen, Norway made a gingerbread town called Pepperkakebyen.[22]

Gallery[edit]

- Gingerbread houses

-

Gingerbread house with candy

-

A gingerbread house with clock and candy decorations

-

Gingerbread house with double doors

-

Gingerbread house with steps and trees

-

Gingerbread house with path

-

Gingerbread house with lighting

-

Gingerbread house with snowman

-

Gingerbread ship

-

Gingerbread house as a Christmas Eve decoration

-

Gingerbread village with model trains

-

Gingerbread house and Elizabeth Tower in London, United Kingdom

See also[edit]

| External video |

|---|

- Gingerbread man

- Lebkuchen

- Aachener Printen

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g «Gingerbread». enotes.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Olver, Lynne. «Traditional Christmas foods» (PDF). The Food Timeline. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013 – via City of Tea Tree Gully.

- ^ La Confrérie du Pain d’Epices, archived from the original on 15 December 2013, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ^ a b Le Pithiviers, archived from the original on 12 December 2013, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ^ Monastère orthodoxe des Saints Grégoire Armeanul et Martin le Seul, archived from the original on 10 January 2014, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ^ «History and tradition». Annas Pepparkakor. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ «Pepparkakan och dess historia». Danska Wienerbageriet. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Campbell Franklin, Linda (1997). 300 Years of Kitchen Collectibles (4th ed.). Iowa, Wisconsin: Krause. p. 183. ISBN 9780896891128.

- ^ «A History of Gingerbread Men». Ferguson Plarre Bakehouses. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- ^ «Gingerbread (more)». Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ «Holiday Tradition with Spicy History». Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 9 December 2001 (p. N-9).

- ^ Brones, Anna. «The Magic of Swedish Gingerbread Cookies». Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ «Gingerbread Architecture Makes Normal Gingerbread Houses Look Pathetic». Huffington Post. 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b Basch, Michelle (5 December 2013). «‘Gingertown’ brings modern twist to gingerbread houses». WTOP-FM.

- ^ «Gingerbread model houses COOP» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ «Pepperkakebyen i Bergen» (in Norwegian and English). Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Rolleiv Solholm (23 November 2009). «Bergen’s «Gingerbread City» vandalized». The Norway Post. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Rubenstein, Steve (3 December 2013). «The great San Francisco gingerbread war commences». San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ List and amount of ingredients used (sign at rear of gingerbread house). Stockholm. 2009.

- ^ a b Herskovitz, Jon (6 December 2013). «With nearly a ton of butter, Texas gingerbread house sets record». Texas A &M University / Reuters.

- ^ «Largest gingerbread village: Chef Jon Lovitch breaks Guinness World Records’ record». World Record Academy. 3 December 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Antonia (22 December 2018). «A brief history of the gingerbread house». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Weaver, William Woys – The Christmas Cook, Three Centuries of American Yuletide Sweets.

- Eliza Leslie Miss Leslie’s New Cookery Book – The Original Classic Edition Miss Leslie’s New Cookery Book, online

External links[edit]

- Gingerbread[permanent dead link] at the Open Directory Project

- Facebook Fan Page

Сладкая история

Пряничный домик – это такое кондитерское изделие, которое… И для чего же делают пряничные домики сегодня? Для детей, для радости, для праздника в доме.

Давным-давно пряничные домики «строили» совсем для других целей. Неизвестно, когда появилось первое съедобное жилище. Но в Древнем Риме это было уже традицией – строить домики из теста, как «жилища» богов в своем домашнем пантеоне.

Такой домик некоторое время украшал семейный алтарь, а затем съедался всеми членами семьи. Причём, съедался он не просто так, а со смыслом. Жители древнего Рима, таким образом, выражали своё почтение к богам и единение.

Сегодня это сложно понять – съесть чужой дом из уважения. У меня есть предположение, что потомки тех римлян сегодня работают в правительстве и в банках. Ну, да Бог с ними.

С приходом христианства о пряничных домиках забыли. И забыли надолго.

Возрождение произошло совершенно случайно. В 1812 году братья Гримм опубликовали свой сборник сказок, в том числе и сказку «Гензель и Греттель». После публикации пряничные домики стали пользоваться невероятной популярностью. Вспомнили древних римлян и рукопись 14 столетия со сказочной страной Кокань (в этой стране, согласно рукописи, был дом из сладостей).

Дети, читавшие сказку, просто мечтали о чудесных пряничных домиках.

Первые домики начали печь родители для своих чад, а затем, как это всегда бывает, началось массовое производство. Появились домики на любой вкус. К праздникам, а особенно к Рождеству, проводились конкурсы на самый красивый домик.

Массовому увлечению способствовало то, что было изобретено специальное пряничное тесто, которое долго не черствело. Домиком можно было любоваться всё Рождество, а потом, с большим аппетитом, домик съесть. Необходимо помнить — пряничное тесто черствеет 2-3 недели. А потом становится невкусным.

С той поры прошло много лет, сменилась мода, но у меня есть уверенность, что и сегодня дети будут радоваться этому чуду. Кто не верит – проверьте. Постройте свой пряничный домик. Тем более, что для современного строения «строительных материалов» существенно больше, чем 200 лет тому назад. Всё зависит только от желания и вашей фантазии.

А потом, это прекрасный повод для совместного творчества. Вместе с ребенком спроектировать, нарисовать, склеить бумажный макет, испечь пряники, построить, а потом вместе украсить. Есть предположение, что ребенок запомнит такой домик на всю свою жизнь.

Пряничный домик — это ощущение дома и домашнего тепла, семейного праздника.

А теперь давайте смотреть, какие бывают пряничные домики, пряничные дворцы и даже пряничные деревни.

Мастер-класс по изготовлению пряничного домика

Желаю всем креативных идей и сладкого настроения!!!

Материал подготовлен Екатериной Воронковой методистом МБУК «Топчихинский ЦДК»