Приблизительное время чтения: 5 мин.

В нашей рубрике «Коротко о празднике» мы рассказываем о двунадесятых и великих праздниках Православной Церкви.

Дата праздника: 28 августа

Слово «успение», однокоренное со словом «усопший», означает «сон». Так в Церкви называют день кончины Пресвятой Богородицы.

Событие праздника Успение Богородицы:

Священное Писание ничего не говорит нам о жизни Пресвятой Богородицы после Воскресения Христова. Поэтому об Успении Богородицы мы знаем из двух латинских трактатов V века и из послания псевдо-Дионисия Ареопагита. Церковь верует, что эти источники сохраняют основу того Предания, которое жило в ранней Церкви.

Все годы после Распятия, Воскресения и Вознесения Иисуса Христа Пресвятая Дева провела большей частью в Иерусалиме, проповедуя Господа наравне с апостолами. Но вот настало время Ее земной кончины.

Однажды во время молитвы Дева Мария увидела Архангела Гавриила, некогда возвестившего Ей великую радость — что Ей суждено стать Матерью Спасителя мира. На сей раз известие было другое: через три дня душа Ее оставит тело. Но Богородица очень обрадовалась. Ведь Ее ожидала встреча с Тем, Кого Она любила гораздо больше, чем жизнь.

Три дня спустя в доме апостола Иоанна, где жила Мария, собрались и другие апостолы: Господь чудесным образом устроил так, что все они вернулись к этому дню из дальних странствий, где проповедовали Христа. Не было только Фомы.

Апостолы стали свидетелями блаженной кончины Святой Девы. Сам Христос, окруженный множеством ангелов, явился, чтобы принять душу Своей Пречистой Матери и возвести Ее в рай.

Тело же Ее апостолы решили похоронить в Гефсимании, где находился Гроб Господень и где погребены были родители Девы Марии и Ее нареченный супруг, праведный Иосиф. Сопровождая гроб, апостолы и другие жители Иерусалима несли светильники и пели псалмы. Иудейский священник Афоний, которого раздражало почитание Иисусовой Матери, толкнул гроб, желая перевернуть его, — и тут же лишился кистей обеих рук: их отсек ангел, невидимо стоявший рядом. «Теперь ты видишь, что Христос истинный Бог», — сказал Афонию апостол Петр. Тот сразу покаялся — и руки срослись.

На третий день к гробнице Божией Матери прибыл апостол Фома. Вход в пещеру открыли, но тела Богоматери там не было! В тот же день, собравшись на общую трапезу, апостолы увидели Пресвятую Деву, шедшую по воздуху со множеством ангелов. Она обратилась к ним со словами: «Радуйтесь! Теперь Я всегда с вами».

Суть праздника Успение Богородицы:

Название праздника — Успение — отражает христианское отношение к смерти. Смерть — не конец нашего существования, а сон: усопший на время оставляет мир, чтобы после всеобщего воскресения снова вернуться к жизни. В Евангелии повествуется о нескольких случаях, когда Христос воскресил умерших, и смерть Он называл при этом именно успением. Не умерла, но спит, — сказал Спаситель об умершей дочери начальника синагоги Иаира (Мф 9:24). И о Лазаре, который заболел и умер: Лазарь, друг наш уснул; но Я иду разбудить его (Ин 11:11). В дни Пасхи в храме звучит песнопение: «Плотию уснув, яко мертв…» — и здесь сну уподоблена смерть Самого Христа.

Вот и праздник Успения Богородицы в народе называют «малой Пасхой». Как Христос в третий день пробудился от смертного сна и воскрес телесно, так и Успение Богородицы оказалось всего лишь кратковременным сном. Христос воззвал Ее от смерти к вечной жизни, и в третий день апостолы убедились, что Она не просто жива: теперь она пребывает с нами всегда и везде, утешая и поддерживая нас на пути ко Христу.

На примере Богородицы мы убеждаемся: Воскресение Христово действительно стало победой над смертью для всех, кто пребывает в общении с Ним и старается следовать Его заповедям.

Фильм «Успение Пресвятой Богородицы»

Почему в христианском мире Успение Пресвятой Богородицы, то есть день Ее смерти, принято отмечать, как великий церковный праздник? Понять духовный смысл одного из важнейших событий церковного года поможет митрополит Иларион (Алфеев). В своем авторском фильме владыка расскажет о том, как принято праздновать Успение в Иерусалиме, на греческом острове Тинос и в испанском городе Эльче. Чем отличается православное Успение от католического праздника Взятия Девы Марии на небо? И почему испанцы считают этот день едва ли не самым важным в году? Фильм митрополита Илариона (Алфеева), студия «НЕОФИТ».

Тропарь Успению Пресвятой Богородицы:

Тропарь, глас 1:

В рождестве девство сохранила eси, во успении мира не оставила eси, Богородице, преставилася eси к животу, Мати сущи Живота,

и молитвами Твоими избавляеши от смерти души наша.

Перевод Ольги Седаковой:

Рождая, сохранила Ты девственность.

Почив, не оставила Ты мира, Богородица:

Ибо перешла к жизни

Ты, истинная Матерь Жизни,

И твоим ходатайством избавляешь

От смерти души наши.

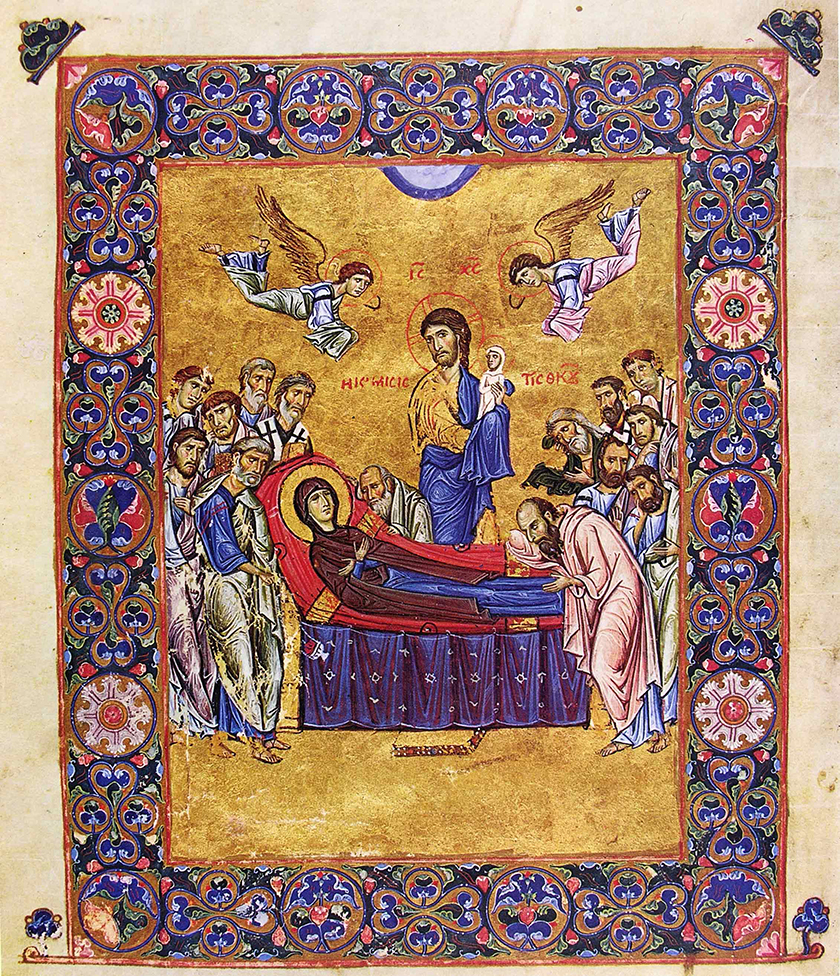

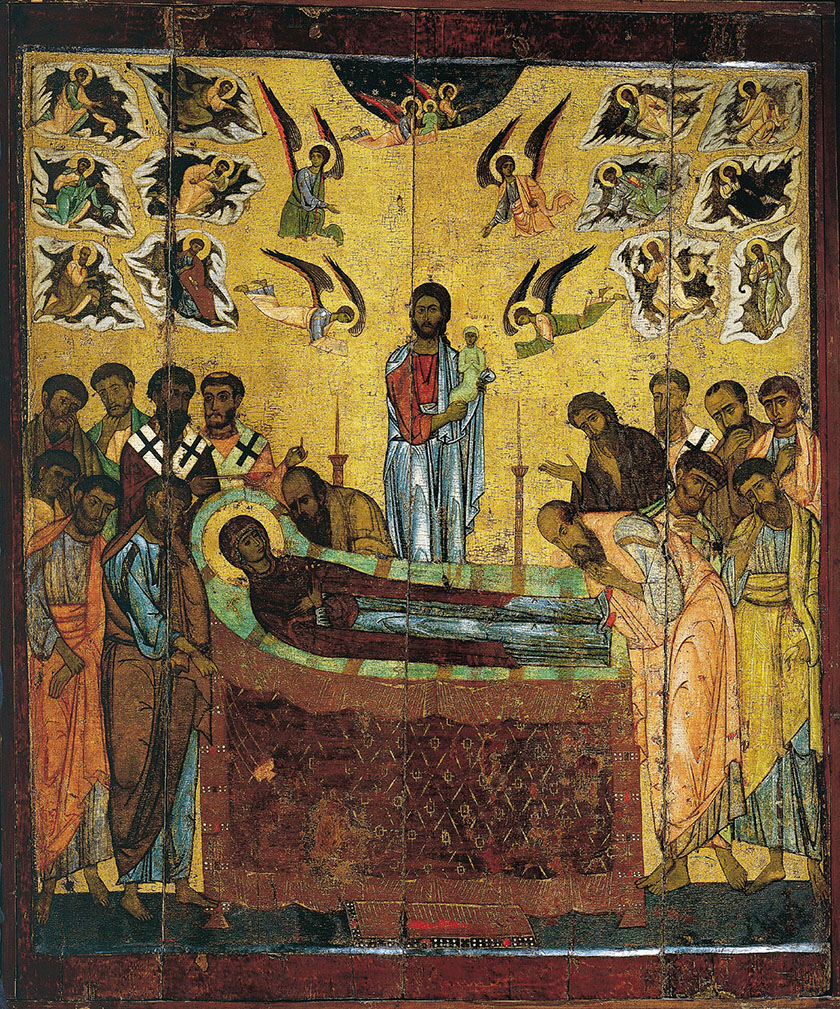

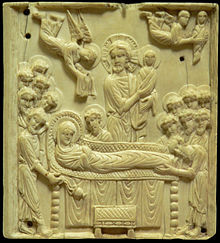

Икона праздника Успение Богородицы:

Богородица на престоле славы возносится в горний Иерусалим.

Овальный нимб и чины ангелов вокруг Христа — символы славы Божией.

Святители Дионисий Ареопагит, Косма Маиумский и Иоанн Дамаскин — творцы посвященных празднику Успения богослужебных текстов.

Младенец на руках у Христа — душа Богородицы

Люди вокруг одра Богородицы — апостолы и плачущие иерусалимские женщины.

Богородица лежит на одре, покрытом тканью багряного цвета. Багрянец — традиционный атрибут власти, в данном случае указывает на царское достоинство Пресвятой Девы.

Иудейский священник Афония, попытавшийся опрокинуть гроб Пресвятой Богородицы во время шествия в Гефсиманию и наказанный ангелом.

3 факта о празднике:

-1-

Успение Пресвятой Богородицы — последний двунадесятый праздник церковного года. Церковное новолетие празднуется 14 сентября (по старому стилю — 1 сентября), так что первым праздником года оказывается Рождество Богородицы, а последним — Ее Успение. Получается, весь год выстраивается в соответствии с событиями жизни Божией Матери.

-2-

Празднику Успения предшествует Успенский пост — самый короткий (всего две недели), но по строгости сопоставимый с Великим постом. Установился он около X века и изначально был частью «компенсаторного» летнего поста для тех, кто по каким-то уважительным причинам не смог выдержать Великий пост (например, находился в длительном плавании).

-3-

В связи с особым почитанием Богородицы бóльшая часть храмов в России начиная с XII–XIII веков освящалась в честь праздника Успения. Первый Успенский собор был построен во Владимире в 1158–1160 годах: князь Андрей Боголюбский возвел его как главный кафедральный собор Руси. В 1326 году был заложен Успенский собор Московского Кремля, ставший усыпальницей Московских Патриархов; как раз в это время из Владимира в Москву переместился митрополит. До XX века московский Успенский собор (перестроенный в 1470-х гг. Аристотелем Фиораванти) оставался главным кафедральным храмом России. В других городах Успенские церкви и соборы возводились в основном по подобию московского.

Читайте также:

Почему Богородица почитается Церковью выше, чем все святые?

Загрузка…

На первый взгляд радоваться дню кончины, даже если она торжественно называется «Успение», это перебор… Похоже на насилие над естественными чувствами, а ответ: «Смерть — это рождение в вечность» кажется натяжкой. Ведь опыт учит: любое столкновение с беспощадной необратимостью смерти сопровождается болью, страхом, тоской, опустошенностью, горем. И Церковь не отрицает право человека на эти чувства. Достаточно сказать, что Иисус плакал у гроба любимого друга Лазаря. Зная, что воскресит Лазаря, Спаситель, как пишет евангелист Иоанн, «прослезился». Почему? Потому что гибель живого — извращение Божьего замысла о человеке: Бог смерти не сотворил, и тление того, что призвано жить, творить, любить, противоестественно, наша душа безошибочно верно реагирует тоской и трепетом на приближение леденящего холода лезвия, безвозвратно рассекающего мир на «здесь» и «там».

Считая день смерти праздником — а это касается не только Успения Пресвятой Богородицы, но и дней памяти святых, которых мы вспоминаем не по их дням рождения, а по дням их ухода, — христианство ни в коем случае не идеализирует смерть. Оно против ее облегченного, инфантильного понимания: «там лучший из миров». Перешел роковую черту, и все, праздник — избавился уж если и не от мук и страданий, то от проблем. Нет! Это губительная ложь, активно навязываемая нам, и особенно молодежи, в том числе культом смерти, культом ее бездарной атрибутики. Ложь, стирающая естественный барьер страха живого перед мертвечиной. И тут Церковь категорична.

«Успение Пресвятой Богородицы», Византия, XV век.

Церковь честно доносит до нас факт воистину поразительный. Вдумайтесь: чувствуя приближение кончины, Богородица молится о том, чтобы непреткновенно, то есть беспрепятственно, пройти посмертные мытарства. С этого места поподробней. Но сначала, что есть мытарства? Испытание нашей бессмертной души, отделившейся от тела и в сопровождении ангелов восходящей к Богу. Частный суд над человеком, подведение итогов земной жизни при участии ангелов и падших духов, которые тут орудия Божьего правосудия. Посмертные мытарства образно сравнивают с таможенными постами, где душу встречают падшие духи, ее истязатели, мытари, старающиеся найти в душе сродство со своею греховностью, обнаружить гнездящиеся в ней страсти, обличить душу в содеянных грехах и затем низвести ее в ад. На мытарствах наши грехи признаются заглаженными, если мы успели или в них покаяться, или совершить противоположные добрые дела. Главный экзамен жизни. И без права пересдачи. Выходит, смерть — последний момент самоопределения личности, итог, когда важно, что ты успел накопить.

Но вернемся к Богородице, обдумаем все по пунктам. Безгрешная. Мать Спасителя, Сына Божьего. Не только смиренно переносящая всю боль, все страдания, но и стойкая, мужественная. Сумевшая понести немыслимо тяжкие испытания — достаточно вспомнить, как Мария стояла при Кресте Своего распятого Сына. Понимающая, Кто есть Ее сын, верующая в Него. Жаждущая встречи с Ним там, в мире горнем. И теперь, учитывая хотя бы то, что мы кратко здесь перечислили, давайте выделим суть.

Чувствуя конец дней земных, Богородица усиленно, сугубо молится. Не потому, что боится смерти, нет, так говорить некорректно! Она осознает мучительную трудность, опасность последнего пути! И просит Господа о помощи. Вот это стоит запомнить всем, кто по легкомыслию считает переход из мира нашего в мир оный чем-то вроде перезагрузки: миг, и ты избавлен от вирусов, болезненных зависаний, сбоев в программе несовершенной действительности. Если бы!

Молитва Пресвятой Богородицы получает ответ. «Будучи итогом жизни, смерть у различных людей должна быть так же не одинакова, как непохожи одна на другую их жизнь и они сами, — читаем у профессора богословия Скабаллановича. — Отсюда самое естественное предположение, что у такой необыкновенной личности, как Пресвятая Дева, с такой исключительной судьбой, и смерть не могла не быть единственной в своем роде. По убеждению Церкви, не только православной, но и католической, кончина Богоматери и была такой, какой не была ни у кого, кроме Нее. Она не изъята была из закона смерти, как и Сын Ее; но Она, подобно Сыну, восторжествовала над смертью, хотя восторжествовала не так славно, очевидно и самостоятельно, как Он. Воскресение Ее произошло сокровенно и долго даже не было общим предметом веры в Церкви».

Время, когда произошло Успение Пресвятой Богородицы, неизвестно. Очевидно, что это было до первых гонений на христиан, развязанных безумцем Нероном в 64 году. Согласно преданию, Мать Христа после распятия Своего Сына скромно жила в доме апостола Иоанна Богослова — в Иерусалиме и Эфесе (западное побережье Малой Азии), проводя время в молитве. Тоскуя и скорбя об ушедшем Сыне, Мария часто приходила на то место, где Она видела Его последний раз — на Елеонскую гору, откуда уже Воскресший Христос много лет назад вознесся на небо. Во время одной из молитв на Елеонской горе перед Богородицей предстал архангел Гавриил и возвестил Ей, что через три дня Она перейдет в вечность.

Мы помним, что архангел Гавриил являлся Деве Марии не единожды. Много лет назад в Назарете он принес Ей благую весть, что Она родит Христа, Сына Божия. На этот раз он тоже принес Ей весть — о том, что через три дня Она закончит Свой скорбный, полный страданий земной путь и перейдет на небо, где будет вечно пребывать со Своим Сыном и Богом Иисусом Христом. Вот как об этом напишет Александр Блок:

- «Уже не шумный и не ярый,

- С волненьем, в сжатые персты

- В последний раз архангел старый

- Влагает белые цветы».

Здесь эпитет «старый» употреблен в смысле «прежний», тот, что был раньше, когда сообщал (в Церкви говорят «благовествовал») Богородице о главном событии Ее жизни — Рождении Спасителя.

Марии, получившей известие о близкой кончине, очень хотелось в последний раз увидеть учеников и сподвижников Иисуса. Но апостолы в то время были далеко от Палестины — каждый из них уже начал свое служение, неся людям благую весть о Воскресении Христовом. И вот тогда, как рассказывает предание, по молитве Божией Матери — а для Пресвятой Богородицы нет ничего невозможного — все апостолы, кроме Фомы, сверхъестественным образом оказались в Иерусалиме, у Нее в доме, на горе Сион. Апостолы и провели с Богородицей последние дни Ее земной жизни.

Как и предрек архангел Гавриил, Успение случилось на третий день. Внезапно горница, где находились Богородица и апостолы, озарилась светом, и все увидели Христа в сиянии божественной славы. Со страхом и трепетом смотрели апостолы на это чудное явление и видели, как душа Божией Матери разлучилась с телом, и Христос принял ее в Свои руки. Как некогда Богоматерь держала на руках Младенца Иисуса, так теперь Ее Сын и Бог, спустившийся с небес к Ее смертному одру, принимал на Свои руки маленькую и хрупкую душу Марии, родившуюся в новую жизнь. Такой, в виде спеленатого младенца, изображается душа Богородицы на православных иконах праздника. И это символично: смерть для живущих истинно христианской жизнью, не конец, а начало, рождение в жизнь вечную. Встреча живой души с Живым Богом.

Божию Матерь похоронили в Гефсиманском саду. Но когда на третий день после погребения в Иерусалим прибыл опять опоздавший апостол Фома (помните, как он пропустил явление апостолам Воскресшего Христа!) и захотел поклониться телу Богородицы, открывшие гробницу увидели там только пустую плащаницу. Подобно Своему Божественному Сыну, Дева Мария была и телом восхищена на небо.

- И стражей вечному покою

- Долины заступила мгла.

- Лишь меж звездою и зарею

- Златятся нимбы без числа.

- А выше, по крутым оврагам

- Поет ручей, цветет миндаль,

- И над открытым саркофагом

- Могильный ангел смотрит в даль,

— так Александр Блок изобразил торжество жизни в миг, который, казалось бы, был кончиной.

«Успение Богородицы», Франсиско Камило. 1666 г.

Богородица родилась среди людей, но в Ней осуществилась вся возможная человечеству святость, потому и говорят: «Пресвятая Дева Мария». Перейдя в мир иной, Богородица не только не оставила людей в одиночестве, наоборот, она усыновила всех нас — объяв всех, даже отъявленных грешников, Своею Любовью как Покровом. Отныне Она стала Матерью всем нам, нашей Милостивой Спасительницей и Заступницей. «Теплой Заступницей мира холодного» называл Богородицу Михаил Лермонтов. и эту материнскую любовь и теплоту может почувствовать каждый, с верой и молитвой обратившийся к Ее Пресвятой Милости.

Наши предки не просто верили в это заступничество и ждали его, праздник Успения Пресвятой Богородицы считался праздником всей Владимиро-Московской Руси. Сделав Владимир столицей, князь Андрей Боголюбский воздвиг там Успенский собор. А когда столицей стала Москва, Успенский храм поставили в Кремле. Огромное количество церквей России было освящено в честь праздника Успения Пресвятой Богородицы — русские помнили милостивую защиту Богородицы в дни бедствий, и уповали на то, что и дальше Божья Матерь не оставит страну.

Но есть еще один повод, по которому Церковь призывает нас радоваться в этот день. «Гроб Богородицы, ставший для Нее дверью к Небесному Царствию, непреложно обещает и нам бессмертие по душе и нетление по телу, истребляя в нас страх смерти», — объясняет святой Иоанн Кронштадтский. Богородица наша, она полностью человеческого рода, только безгрешна. Значит, душа действительно бессмертна и воскресение возможно и для человеков. Отсюда и радость христиан, отсюда еще одно название праздника Успения — Богородичная Пасха.

Как и всем большим церковным праздникам, дню Успения Пресвятой Богородицы предшествовал пост, двухнедельный строгий Успенский пост, который сегодня закончился, и который должен был духовно подготовить верующих к самому празднику.

Русская Православная Церковь

-

23 Декабрь 2022

26 декабря, в понедельник, в 19.00 в Лектории на Воробьевых горах храма Троицы и МГУ, к 100-летию СССР состоится выступление Михаил а Борисович а С МОЛИНА , историк а русской консервативной мысли, кандидат а исторических наук, директор а Фонда «Имперское возрождение» , по теме «Учреждение СССР — уничтож ение историческ ой Росси и » .

Адрес: Косыгина, 30.

Проезд: от м.Октябрьская, Ленинский проспект, Ломоносовский проспект, Киевская маршрут№297 до ост. Смотровая площадка. -

28 Ноябрь 2022

- Все новости

28 августа по новому стилю и 15 августа по старому стилю Русская Православная Церковь отмечает праздник Успения Пресвятой Владычицы нашей Богородицы и Приснодевы Марии. Успение Богородицы – праздник, посвященный событию, которое не описывается в Библии, но о котором известно благодаря Преданию Церкви. Само слово «успение» на современный русский язык можно перевести как «смерть».

Пресвятая Матерь Божия после вознесения Иисуса осталась на попечение апостола Иоанна Богослова. Когда царь Ирод подверг гонению христиан, Богородица удалилась вместе с Иоанном в Эфес и жила там в доме его родителей.

Здесь Она постоянно молилась о том, чтобы Господь поскорее взял Ее к Себе. Во время одной из таких молитв, которую Богородица совершала на месте вознесения Христа, Ей явился архангел Гавриил и возвестил, что через три дня окончится Ее земная жизнь и Господь возьмет Ее к Себе.

Перед кончиной Пресвятая Дева Мария хотела увидеть всех апостолов, которые к тому времени разошлись по разным местам проповедовать христианскую веру. Несмотря на это, желание Богородицы исполнилось: Святой Дух чудесным образом собрал апостолов у ложа Пресвятой Богородицы, на котором Она молилась и ожидала Своей кончины. Сам Спаситель в окружении ангелов сошел к Ней, чтобы забрать Ее душу с Собой.

Пресвятая Богородица обратилась ко Господу с благодарственной молитвой и просила благословить всех почитающих Ее память. Она также проявила огромное смирение: достигнув святости, с которой не сравнится ни один человек, будучи Честнейшей Херувим и Славнейшей без сравнения Серафим, Она молила Сына Своего защитить Ее от темной сатанинской силы и от мытарств, которые проходит после смерти каждая душа. Увидевшись с апостолами, Богоматерь радостно предала Свою душу в руки Господа, и тотчас раздалось ангельское пение.

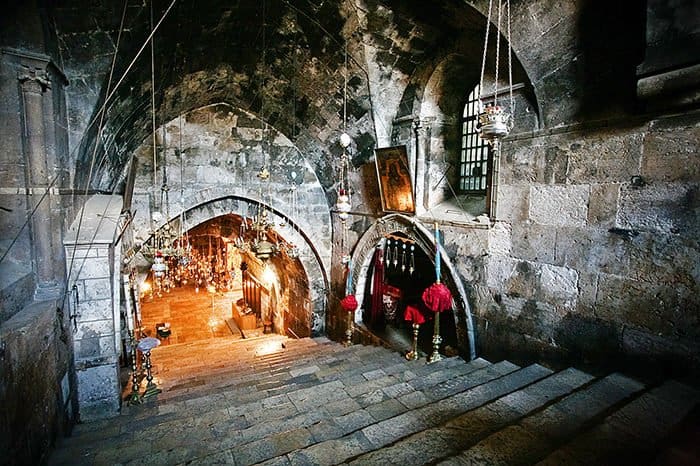

После кончины гроб с телом Пречистой Девы был отнесен апостолами в Гефсиманию и там захоронен в пещере, вход которой завалили камнем. После похорон апостолы еще три дня оставались у пещеры и молились. Опоздавший к погребению апостол Фома был так опечален тем, что не успел поклониться праху Богородицы, что апостолы позволили открыть вход в пещеру и могилу, чтобы он мог поклониться святым останкам. Открыв гроб, они обнаружили, что там нет тела Богородицы, и таким образом убедились в Ее чудесном телесном вознесении на Небо. Вечером того же дня собравшимся на ужин апостолам явилась Сама Матерь Божия и сказала: «Радуйтесь! Я с вами – во все дни».

Кончину Богородицы Церковь называет успением, а не смертью, потому что обычная человеческая смерть, когда тело возвращается в землю, а дух – Богу, не коснулась Благодатной. «Побеждены законы природы в Тебе, Дева Чистая, – воспевает Святая Церковь в тропаре праздника, – в рождении сохраняется девство, и со смертию сочетается жизнь: пребывая по рождении Девою и по смерти Живою, Ты спасаешь всегда, Богородица, наследие Твое».

Она лишь уснула, чтобы в то же мгновение пробудиться для жизни вечноблаженной и после трех дней с нетленным телом вселиться в небесное нетленное жилище. Она опочила сладким сном после тяжкого бодрствования Ее многоскорбной жизни и «преставилась к Животу», то есть Источнику Жизни, как Матерь Жизни, избавляя молитвами Своими от смерти души земнородных, вселяя в них Успением Своим предощущение жизни вечной. Поистине, «в молитвах неусыпающую Богородицу и в предстательствах непреложное упование, гроб и умерщвление не удержаста».

История праздника Успения Пресвятой Богородицы

Успение Пресвятой Богородицы является одним из главных богородичных праздников Церкви.

Некоторые данные указывают на связь этого праздника с древнейшим Богородичным празднованием – «Собором Пресвятой Богородицы», который доныне совершается на следующий день после Рождества Христова. Так, в коптском календаре VII в. 16 января, т. е. вскоре после отдания Богоявления, празднуется «рождение Госпожи Марии», а в календаре IX в. в то же число – «смерть и воскресение Богородицы» (в памятниках коптской и абиссинской Церквей XIV–XV вв., сохранявших вследствие своей изолированности древнюю литургическую практику, 16 января положено воспоминание Успения, а 16 августа – Вознесения Богоматери на небо).

В греческих Церквах достоверные свидетельства об этом празднике известны с VI в., когда, по свидетельству поздневизантийского историка Никифора Каллиста (XIV в.), император Маврикий (592–602 гг.) повелел праздновать Успение 15 августа (для западной Церкви мы имеем свидетельство не VI, а V в. – сакраментарий папы Геласия I). Тем не менее можно говорить и о более раннем существовании праздника Успения, например, в Константинополе, где уже в IV в. существовало множество храмов, посвященных Богородице.

Один из них – Влахернский, построенный императрицей Пульхерией. Здесь ею были положены погребальные пелены (риза) Богоматери. Архиеп. Сергий (Спасский) в своем «Полном месяцеслове Востока» указывает на то, что согласно свидетельству Стишного пролога (древнего месяцеслова в стихах) Успение праздновалось во Влахернах 15 августа и что свидетельство Никифора следует понимать в особом ключе: Маврикий сделал праздник только более торжественным. Начиная с VIII в. мы имеем многочисленные свидетельства о празднике, которые позволяют проследить его историю вплоть до настоящего времени.

Читайте также – Иконография Успения Богородицы: что в ней есть и чего в ней нет

Успение Богородицы — иконы

Миниатюра из Евангелия императора Никифора II Фоки. XI в.

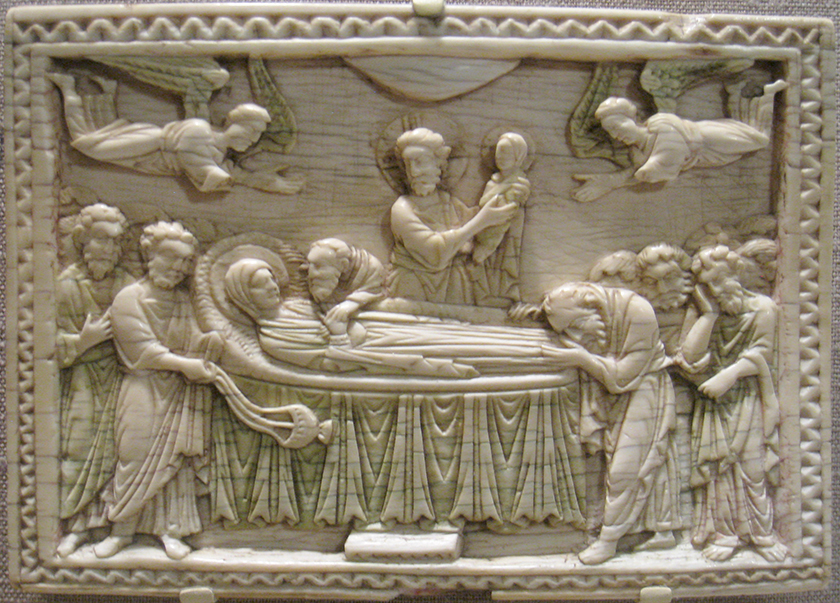

Резьба по кости. Византия. Константинополь. X в.

Икона. ок. 1200 г. Новгород

Успение Пресвятой Богородицы; Балканы. Сербия. Сопочаны; XIII в.

Молитвы на праздник Успения Богородицы

Тропарь, глас 1

В рождестве девство сохранила еси,/ во успении мира не оставила еси, Богородице,/ преставилася еси к животу,/ Мати сущи Живота,// и молитвами Твоими избавляеши от смерти души наша.

Кондак, глас 2

В молитвах Неусыпающую Богородицу/ и в предстательствах непреложное упование/ гроб и умерщвление не удержаста:/ якоже бо Живота Матерь/ к животу престави// во утробу Вселивыйся приснодевственную.

Величание

Величаем Тя, /Пренепорочная Мати Христа Бога нашего, /и всеславное славим /Успение Твое.

Избранные песнопения службы Успения в исполнении хора Киево-Печерской лавры и хора Свято-Троицкой Сергиевой лавры и Московских духовных академии и семинарии под управлением архим. Матфея.

Тропарь

В рождестве девство сохранила eси, во успении мира не оставила eси, Богородице, преставилася eси к Животу, Мати сущи Живота: и молитвами Твоими избавляеши от смерти души наша.

Кондак

(Хор Киево-Печерской лавры)

(Хор Киево-Печерской лавры)

В молитвах неусыпающую Богородицу, и в предстательствах непреложное упование, гроб и умерщвление не удержаста: якоже бо Живота Матерь, к животу престави, во утробу Вселивыйся приснодевственную.

Читайте также — Успение в Первом уделе Божией Матери (+ ФОТО + АУДИО)

Величание

(Хор Киево-Печерской лавры)

Величаем Тя, Пренепорочная Мати Христа Бога нашего, и всеславное славим Успение Твое.

Стихира на Успение

Скачать (Объединенный хор Свято-Троицкой Сергиевой лавры и Московских духовных академии и семинарии под управлением архим. Матфея)

О дивное чудо! Источник Жизни во гробе полагается, и лествица к небеси гроб бывает: веселися Гефсимание, Богородичен святый доме. Возопием вернии, Гавриила имуще чиноначальника: Благодатная радуйся, с Тобою Господь, подаяй мирови Тобою велию милость.

Стихира по пятидесятом псалме

Егда преставление пречистаго Твоего тела готовляшеся, тогда апостоли обстояще одр, с трепетом зряху Тя. И ови убо взирающе на тело, ужасом одержими бяху, Петр же со слезами вопияше Ти: о Дево, вижду Тя ясно простерту просту, Живота всех, и удивляюся: в Нейже вселися будущия жизни наслаждение! Но о Пречистая, молися прилежно Сыну и Богу Твоему, спастися стаду Твоему невредиму.

Светилен

(Хор Киево-Печерской лавры)

Апостоли от конец совокупльшеся зде, в Гефсиманийстей веси погребите тело Мое: и Ты, Сыне и Боже Мой, приими дух Мой.

Стихиры на хвалитех

(Хор Киево-Печерской лавры)

На безсмертное Твое успение, Богородице Мати Живота, облацы апостолы по воздуху восхищаху, и по миру разсеянныя во едином лице предсташа пресвятому Твоему телу, еже и погребше честно, глас Тебе Гавриилов поюще, вопияху: радуйся, Благодатная Дево, Мати Безневестная, Господь с Тобою. С нимиже, яко Сына Твоего и Бога нашего, моли спастися душам нашим.

Задостойник

(Хор Киево-Печерской лавры)

Ангели успение Пречистыя видевше удивишася, како Дева восходит от земли на небо. Побеждаются естества уставы в Тебе, Дево Чистая: девствует бо рождество, и живот предобручает смерть. По рождестве Дева, и по смерти жива, спасаеши присно, Богородице, наследие Твое.

Проповеди на праздник Успения Богородицы

Слово на Успение Пресвятой Богородицы владыки Василия (Родзянко)

Проповедь архимандрита Иоанна Крестьянкина в праздник Успения Пресвятой Богородицы

Проповедь Святейшего Патриарха Кирилла в праздник Успения Пресвятой Владычицы нашей Богородицы и Приснодевы Марии после Божественной литургии в Патриаршем Успенском соборе Московского Кремля 28 августа 2012 года.

Вы прочитали статью Успение Богородицы: иконы, история, молитвы. На эту тему Вы можете прочитать также и другие материалы:

- О, дивное чудо! Песнопения на Успение Пресвятой Богородицы

- Гробница Божией Матери: «Во Успении мира не оставила еси…»

- Успение в Тбилиси (ФОТО)

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

«Assunta» redirects here. For the hospital in Malaysia, see Assunta Hospital.

| Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary | |

|---|---|

A famous treatment in Western art, Titian’s Assumption, 1516–1518 |

|

| Also called |

|

| Observed by |

|

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | the bodily taking up of Mary, the mother of Jesus into Heaven |

| Observances | Attending Mass or service |

| Date |

|

| Frequency | Annual |

Memorial in Youghal, Ireland, to the promulgation of the dogma of the Assumption

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it in 1950 in his apostolic constitution Munificentissimus Deus as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by God that the immaculate Mother of God, Mary ever virgin, when the course of her earthly life was finished, was taken up body and soul into the glory of heaven.[2]

The declaration was built upon the 1854 dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, which declared that Mary was conceived free from original sin, and both have their foundation in the concept of Mary as the Mother of God.[3] It leaves open the question of whether Mary died or whether she was raised to eternal life without bodily death.[2]

The equivalent belief (but not held as dogma) in the Eastern Orthodox Church is the Dormition of the Mother of God or the «Falling Asleep of the Mother of God».

The word ‘assumption’ derives from the Latin word assūmptiō meaning «taking up».

Traditions relating to the Assumption[edit]

In some versions of the assumption narrative, the assumption is said to have taken place in Ephesus, in the House of the Virgin Mary. This is a much more recent and localized tradition. The earliest traditions say that Mary’s life ended in Jerusalem (see Tomb of the Virgin Mary). By the 7th century, a variation emerged, according to which one of the apostles, often identified as Thomas the Apostle, was not present at the death of Mary but his late arrival precipitates a reopening of Mary’s tomb, which is found to be empty except for her grave clothes. In a later tradition, Mary drops her girdle down to the apostle from heaven as testament to the event.[4] This incident is depicted in many later paintings of the Assumption.

Teaching of the Assumption of Mary became widespread across the Christian world, having been celebrated as early as the 5th century and having been established in the East by Emperor Maurice around AD 600.[5] John Damascene records the following:

St. Juvenal, Bishop of Jerusalem, at the Council of Chalcedon (451), made known to the Emperor Marcian and Pulcheria, who wished to possess the body of the Mother of God, that Mary died in the presence of all the Apostles, but that her tomb, when opened upon the request of St. Thomas, was found empty; wherefrom the Apostles concluded that the body was taken up to heaven.[6]

History[edit]

Some scholars argue that the Dormition and Assumption traditions can be traced early in church history in apocryphal books, with Shoemaker stating,

Other scholars have similarly identified these two apocrypha as particularly early. For instance, Baldi, Masconi, and Cothenet analyzed the corpus of Dormition narratives using a rather different approach, governed primarily by language tradition rather than literary relations, and yet all agree that the Obsequies (i.e., the Liber Requiei) and the Six Books apocryphon reflect the earliest traditions, locating their origins in the second or third century.[7]

Scholars of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum «argued that during or shortly after the apostolic age a group of Jewish Christians in Jerusalem preserved an oral tradition about the end of the Virgin’s life». Thus, by pointing to oral tradition, they argued for the historicity of the assumption and Dormition narratives. However, Shoemaker notes they fail to take into account the various «strikingly diverse traditions» that the Assumption seems to come from, mainly, «a great variety of original types», rather than «a single unified tradition». Regardless, Shoemaker states even those scholars note «belief in the Virgin’s Assumption is the final dogmatic development, rather than the point of origin, of these traditions». [8]

According to Stephen J. Shoemaker, the first known narrative to address the end of Mary’s life and her assumption is the apocryphal third- and possibly second-century, Liber Requiei Mariae («Book of Mary’s Repose»).[9] Shoemaker asserts that «this earliest evidence for the veneration of Mary appears to come from a markedly heterodox theological milieu».[10]

Other early sources, less suspect in their content, also contain the assumption. «The Dormition/Assumption of Mary» (attributed to John the Theologian or «Pseudo-John»), another anonymous narrative, is possibly dated to the fourth century, but is dated by Shoemaker as later.[11] The «Six Books Dormition Apocryphon», dated to the early fourth century,[10] likewise speaks of the Assumption. «Six Books Dormition Apocryphon» was perhaps associated with the Collyridians who were condemned by Epiphanius of Salamis «for their excessive devotion to the Virgin Mary».[10]

Shoemaker mentions that «the ancient narratives are neither clear nor unanimous in either supporting or contradicting the dogma» of the assumption.[12]

In accordance with Stephen J. Shoemaker «there is no evidence of any tradition concerning Mary’s Dormition and Assumption from before the fifth century. The only exception to this is Epiphanius’ unsuccessful attempt to uncover a tradition of the end of Mary’s life towards the end of the fourth century.»[13] The New Testament is silent regarding the end of her life, the early Christians produced no accounts of her death, and in the late 4th century Epiphanius of Salamis wrote he could find no authorized tradition about how her life ended.[14] Nevertheless, although Epiphanius could not decide on the basis of biblical or church tradition whether Mary had died or remained immortal, his indecisive reflections suggest that some difference of opinion on the matter had already arisen in his time,[15] and he identified three beliefs concerning her end: that she died a normal and peaceful death; that she died a martyr; and that she did not die.[15] Even more, in another text Epiphanius stated that Mary was like Elijah because she never died but was assumed like him.[16]

Notable later apocrypha that mention the Assumption include De Obitu S. Dominae and De Transitu Virginis, both probably from the 5th century, with further versions by Dionysius the Areopagite, and Gregory of Tours, among others.[17] The Transitus Mariae was considered as apocrypha in a 6th-century work called Decretum Gelasianum,[18] but by the early 8th century the belief was so well established that John of Damascus could set out what had become the standard Eastern tradition, that «Mary died in the presence of the Apostles, but that her tomb, when opened, upon the request of St Thomas, was found empty; wherefrom the Apostles concluded that the body was taken up to heaven.»[19]

Euthymiac History, from sixth century, contains one of the earliest reference to the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary.[20]

The Feast of the Dormition, imported from the East, arrived in the West in the early 7th century, its name changing to Assumption in some 9th century liturgical calendars.[21] In the same century Pope Leo IV (reigned 847–855) gave the feast a vigil and an octave to solemnise it above all others, and Pope Nicholas I (858–867) placed it on a par with Christmas and Easter, tantamount to declaring Mary’s translation to Heaven as important as the Incarnation and Resurrection of Christ.[21] In the 10th century the German nun Elisabeth of Schönau was reportedly granted visions of Mary and her son which had a profound influence on the Western Church’s tradition that Mary was assumed in body and soul into Heaven,[21] and Pope Benedict XIV (1740–1758) declared it «a probable opinion, which to deny were impious and blasphemous».[22]

Scriptural basis[edit]

The Basilica of the Assumption of Our Lady in Mosta, Malta. The church is also known as Mosta Dome or as Mosta Rotunda. The façade of the basilica is decorated for the Feast of the Assumption, celebrated on 15 August.

Pope Pius, in promulgating Munificentissimus Deus, stated that «All these proofs and considerations of the holy Fathers and the theologians are based upon the Sacred Writings as their ultimate foundation.» The pope did not advance any specific text as proof of the doctrine, but one senior advisor, Father Jugie, expressed the view that Revelation 12:1–2 was the chief scriptural witness to the assumption:[23]

And a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars; and she was with child …

The symbolism of this verse is based on the Old Testament, where the sun, moon, and eleven stars represent the patriarch Jacob, his wife, and eleven of the twelve tribes of Israel, who bow down before the twelfth star and tribe, Joseph, and verses 2–6 reveal that the woman is an image of the faithful community.[24] The possibility that it might be a reference to Mary’s immortality was tentatively proposed by Epiphanius in the 4th century, but while Epiphanius made clear his uncertainty and did not advocate the view, many later scholars did not share his caution and its reading as a representation of Mary became popular with certain Roman Catholic theologians.[25]

Many of the bishops cited Genesis 3:15, in which God is addressing the serpent in the Garden of Eden, as the primary confirmation of Mary’s assumption:[26]

Enmity will I set between you and the woman, between your seed and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church affirms that the account of the fall in Genesis 3 uses figurative language, and that the fall of mankind, by the seductive voice of the snake in the bible, represents the fallen angel, Satan.[27] Similarly, the great dragon in Revelation is a representation of Satan, identified with the serpent from the garden who has enmity with the woman. Though the woman in revelation represents the people of God, faithful Israel and the Church, Mary is considered the Mother of the Church.[28] Therefore, in Catholic thought there is an association between this heavenly woman and Mary’s Assumption.

Some scholars conclude that no messianic prophecy was originally intended,[29] that in the Hebrew Bible the serpent is not satanic, and the verse is simply a record of the enmity between humans and snakes (although a memory of the ancient Canaanite myth of a primordial sea-serpent may stand behind them, albeit at a distance).[30] But although the verse speaks literally about mankind’s relationship with snakes, there is also a metaphorical overtone: a door has been opened to a dark power and there is no promise of victory, but rather a warning of ongoing conflict.[31]

Among the many other passages noted by the pope[which?] were the following:[26]

- Psalm 132:8, greeting the return of the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem («Arise, O Lord, into your resting place, you and the ark which you have sanctified!»), where the ark is taken as the prophetic «type» of Mary;[32]

- Revelation 11:19, in which John sees the ark of the covenant in heaven (this verse immediately precedes the vision of the woman clothed with the sun);

- Luke 1:28, in which the Archangel Gabriel greets Mary with the words, «Hail Mary, full of grace», since Mary’s bodily assumption is a natural consequence of being full of grace;

- 1 Corinthians 15:23 and Matthew 27:52–53, concerning the certainty of bodily resurrection for all who have faith in Christ.

Assumption versus Dormition[edit]

The Dormition: ivory plaque, late 10th-early 11th century (Musée de Cluny)

Some Catholics believe that Mary died before being assumed, but they believe that she was miraculously resurrected before being assumed. Others believe she was assumed bodily into Heaven without first dying.[33][34] Either understanding may be legitimately held by Catholics, with Eastern Catholics observing the Feast as the Dormition.

Many theologians note by way of comparison that in the Catholic Church the Assumption is dogmatically defined, whilst in the Eastern Orthodox tradition the Dormition is less dogmatically than liturgically and mystically defined. Such differences spring from a larger pattern in the two traditions, wherein Catholic teachings are often dogmatically and authoritatively defined – in part because of the more centralized structure of the Catholic Church – whilst in Eastern Orthodoxy many doctrines are less authoritative.[35]

The Latin Catholic Feast of the Assumption is celebrated on 15 August and the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholics celebrate the Dormition of the Mother of God (or Dormition of the Theotokos, the falling asleep of the Mother of God) on the same date, preceded by a 14-day fast period. Eastern Christians believe that Mary died a natural death, that her soul was received by Christ upon death, that her body was resurrected after her death and that she was taken up into heaven bodily in anticipation of the general resurrection.

Orthodox tradition is clear and unwavering in regard to the central point [of the Dormition]: the Holy Virgin underwent, as did her Son, a physical death, but her body – like His – was afterwards raised from the dead and she was taken up into heaven, in her body as well as in her soul. She has passed beyond death and judgement and lives wholly in the Age to Come. The Resurrection of the Body … has in her case been anticipated and is already an accomplished fact. That does not mean, however, that she is dissociated from the rest of humanity and placed in a wholly different category: for we all hope to share one day in that same glory of the Resurrection of the Body that she enjoys even now.[36]

Protestant views[edit]

The Assumption of Mary, Rubens, 1626

Views differ within Protestantism, with those with a theology closer to Catholicism sometimes believing in a bodily assumption whilst most Protestants do not.

Lutheran views[edit]

The Feast of the Assumption of Mary was retained by the Lutheran Church after the Reformation.[37] Evangelical Lutheran Worship designates August 15 as a lesser festival named «Mary, Mother of Our Lord» while the current Lutheran Service Book formally calls it «St. Mary, Mother of our Lord».[37]

Anglican views[edit]

Within Anglican doctrine the Assumption of Mary is either rejected or regarded as adiaphora («a thing indifferent»);[38] it therefore disappeared from Anglican worship in 1549, partially returning in some branches of Anglicanism during the 20th century under different names. A Marian feast on 15 August is celebrated by the Church of England as a non-specific feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a feast called by the Scottish Episcopal Church simply «Mary the Virgin»,[39][40][41] and in the US-based Episcopal Church it is observed as the feast of «Saint Mary the Virgin: Mother of Our Lord Jesus Christ»,[42]

while other Anglican provinces have a feast of the Dormition[39] – the Anglican Church of Canada for instance marks the day as the «Falling Asleep of the Blessed Virgin Mary».[43]

The Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission, which seeks to identify common ground between the two communions, released in 2004 a non-authoritative declaration meant for study and evaluation, the «Seattle Statement»; this «agreed statement» concludes that «the teaching about Mary in the two definitions of the Assumption and the Immaculate Conception, understood within the biblical pattern of the economy of hope and grace, can be said to be consonant with the teaching of the Scriptures and the ancient common traditions».[44]

Other Protestant views[edit]

The Protestant reformer Heinrich Bullinger believed in the assumption of Mary. His 1539 polemical treatise against idolatry[45] expressed his belief that Mary’s sacrosanctum corpus («sacrosanct body») had been assumed into heaven by angels:

|

Hac causa credimus ut Deiparae virginis Mariae purissimum thalamum et spiritus sancti templum, hoc est, sacrosanctum corpus ejus deportatum esse ab angelis in coelum.[46] |

For this reason we believe that the Virgin Mary, Begetter of God, the most pure bed and temple of the Holy Spirit, that is, her most holy body, was carried to heaven by angels.[47] |

Feasts and related fasting period[edit]

Orthodox Christians fast fifteen days prior to the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, including abstinence from sexual relations.[48] Fasting in the Orthodox tradition refers to not consuming a meal until evening.[49]

The Assumption is important to many Christians, especially Catholics and Orthodox, as well as many Lutherans and Anglicans, as the Virgin Mary’s heavenly birthday (the day that Mary was received into Heaven). Belief about her acceptance into the glory of Heaven is seen by some Christians as the symbol of the promise made by Jesus to all enduring Christians that they too will be received into paradise. The Assumption of Mary is symbolised in the Fleur-de-lys Madonna.

The present Italian name of the holiday, Ferragosto, may derive from the Latin name, Feriae Augusti («Holidays of the Emperor Augustus»),[50] since the month of August took its name from the emperor. The feast was introduced by Bishop Cyril of Alexandria in the 5th century. In the course of Christianization, he put it on 15 August. In the middle of August, Augustus celebrated his victories over Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra at Actium and Alexandria with a three-day triumph. The anniversaries and later only 15 August were public holidays from then on throughout the Roman Empire.[51]

The Solemnity of the Assumption on 15 August was celebrated in the Eastern Church from the 6th century. The Western Church adopted this date as a Holy Day of Obligation to commemorate the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a reference to the belief in a real, physical elevation of her sinless soul and incorrupt body into Heaven.

Public holidays[edit]

Patoleo (sweet rice cakes) are the pièce de résistance of the Assumption feast celebration among Goan Catholics.

Assumption Day on 15 August is a nationwide public holiday in Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chile, Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cyprus, East Timor, France, Gabon, Greece, Georgia, Republic of Guinea, Haiti, Italy, Lebanon, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Republic of North Macedonia, Madagascar, Malta, Mauritius, Republic of Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro (Albanian Catholics), Paraguay, Poland (coinciding with Polish Army Day), Portugal, Romania, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Slovenia, Spain, Syria, Tahiti, Togo, and Vanuatu;[52] and was also in Hungary until 1948.

It is also a public holiday in parts of Germany (parts of Bavaria and Saarland) and Switzerland (in 14 of the 26 cantons). In Guatemala, it is observed in Guatemala City and in the town of Santa Maria Nebaj, both of which claim her as their patron saint.[53] Also, this day is combined with Mother’s Day in Costa Rica and parts of Belgium.

Prominent Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox countries in which Assumption Day is an important festival but is not recognized by the state as a public holiday include the Czech Republic, Ireland, Mexico, the Philippines and Russia. In Bulgaria, the Feast of the Assumption is the biggest Eastern Orthodox Christian celebration of the Holy Virgin. Celebrations include liturgies and votive offerings. In Varna, the day is celebrated with a procession of a holy icon, and with concerts and regattas.[54]

In many places, religious parades and popular festivals are held to celebrate this day. In Canada, Assumption Day is the Fête Nationale of the Acadians, of whom she is the patron saint. Some businesses close on that day in heavily francophone parts of New Brunswick, Canada. The Virgin Assumed in Heaven is also patroness of the Maltese Islands and her feast, celebrated on 15 August, apart from being a public holiday in Malta is also celebrated with great solemnity in the local churches especially in the seven localities known as the Seba’ Santa Marijiet. The Maltese localities which celebrate the Assumption of Our Lady are: Il-Mosta, Il-Qrendi, Ħal Kirkop, Ħal Għaxaq, Il-Gudja, Ħ’Attard, L-Imqabba and Victoria. The hamlet of Praha, Texas holds a festival during which its population swells from approximately 25 to 5,000 people.

In Anglicanism and Lutheranism, the feast is now often kept, but without official use of the word «Assumption». In Eastern Orthodox churches following the Julian Calendar, the feast day of Assumption of Mary falls on 28 August.

Art[edit]

The earliest known use of the Dormition is found on a sarcophagus in the crypt of a church in Zaragoza in Spain dated c. 330.[17] The Assumption became a popular subject in Western Christian art, especially from the 12th century, and especially after the Reformation, when it was used to refute the Protestants and their downplaying of Mary’s role in salvation.[55] Angels commonly carry her heavenward where she is to be crowned by Christ, while the Apostles below surround her empty tomb as they stare up in awe.[55] Caravaggio, the «father» of the Baroque movement, caused a stir by depicting her as a decaying corpse, quite contrary to the doctrine promoted by the church;[56] more orthodox examples include works by El Greco, Rubens, Annibale Carracci, and Nicolas Poussin, the last replacing the Apostles with putti throwing flowers into the tomb.[55]

See also[edit]

- Assumption, a disambiguation page which includes many places named after the Assumption of Mary

- Ascension of Jesus

- Coronation of Mary

- Resurrection of Jesus Christ

- Entering heaven alive

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Feast of the Assumption of the Holy Mother-of-God». The Armenian Church. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ a b Collinge 2012, p. 53.

- ^ Kerr 2001, p. 746.

- ^ Ante-Nicene Fathers. The Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325, vol. 8 p. 594

- ^ Alban Butler, Paul Burns (1998). Butler’s Lives of the Saints. ISBN 0860122573. pp. 140–141

- ^ William Saunders (1996). «The Assumption of Mary». EWTN. Archived 16 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shoemaker, Stephen. «The Ancient Dormition Apocrypha and the Origins of Marian Piety: Early Evidence of Marian Intercession from Late Ancient Palestine (Uncorrected page proofs)».

- ^ Shoemaker 2002, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Shoemaker 2016, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Shoemaker 2016, p. 25.

- ^ Patrick Truglia, «Original Sin in The Byzantine Dormition Narratives», Revista Teologica, Issue 4 (2021): 9 (Footnote 30).

- ^ Shoemaker 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Shoemaker 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Shoemaker 2002, pp. 11–12, 26.

- ^ a b Shoemaker 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Shoemaker, Stephen J. (2008). «Epiphanius of Salamis, the Kollyridians, and the Early Dormition Narratives: The Cult of the Virgin in the Fourth Century». Journal of Early Christian Studies 16 (3): 371–401. ISSN 1086-3184.

- ^ a b Zirpolo 2018, p. 213.

- ^ Shoemaker 2002, p. 17 and fn 27.

- ^ Jenkins 2015, p. unpaginated.

- ^ John Wortley, «The Marian Relics at Constantinople», Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 45 (2005), pp. 171–187, esp. 181–182.

- ^ a b c Warner 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Wagner 2020, p. 95.

- ^ O’Carroll 2000, p. 56.

- ^ Beale & Campbell 2015, p. 243.

- ^ Shoemaker 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b Miravalle 2006, p. 73.

- ^ «Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText». Holy See. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Williamson, Peter (2015). Catholic Christian Commentary on Sacred Scripture: Revelation. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. pp. 205–220. ISBN 978-0801036507.

- ^ Arnold 2009, p. 69.

- ^ Alter 1997, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Goldingay 2020, p. unpaginated.

- ^ «Assumption of Mary: Scriptural Support». University of Dayton, Ohio.

- ^ The Catholicism Answer Book: The 300 Most Frequently Asked Questions by John Trigilio, Kenneth Brighenti 2007 ISBN 1402208065 p. 64

- ^ Shoemaker 2016, p. 201

- ^ See «Three Sermons on the Dormition of the Virgin» by John of Damascus, from the Medieval Sourcebook

- ^ Bishop Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia, in: Festal Menaion [London: Faber and Faber, 1969], p. 64.

- ^ a b Beane, Larry (15 August 2019). «The Feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary». Gottesdienst. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

Many early Lutherans retained the Feast of the Assumption in the liturgical calendar, while recognizing it as a speculation rather than a dogma. However, Pope Pius XII dogmatized this belief in 1950 in his decree Munificentissimus Dei, thus imposing it as doctrine upon Roman Catholics. … Today’s feast is described in Lutheran Service Book as ‘St. Mary, Mother of our Lord’.

- ^ Williams, Paul (2007). pp. 238, 251, quote: «Where Anglican writers discuss the doctrine of the Assumption, it is either rejected or held to be of the adiaphora.»

- ^ a b Williams, Paul (2007). p. 253, incl. note 54.

- ^ The Church of England, official website: The Calendar. Accessed 17 July 2018

- ^ The Scottish Episcopal Church, official website: Calendar and Lectionary. Accessed 17 July 2018

- ^ The Episcopal Church. «Saint Mary the Virgin: Mother of Our Lord Jesus Christ». Liturgical Calendar. New York: The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society, The Episcopal Church. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ «The Calendar». Prayerbook.ca. p. ix. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ «Mary: Grace and Hope in Christ». Vatican.va. 26 June 2000. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

There is no direct testimony in Scripture concerning the end of Mary’s life. However, certain passages give instances of those who follow God’s purposes faithfully being drawn into God’s presence. Moreover, these passages offer hints or partial analogies that may throw light on the mystery of Mary’s entry into glory.

- ^ De origine erroris libri duo [On the Origin of Error, Two Books] [1]. «In the De origine erroris in divorum ac simulachrorum cultu he opposed the worship of the saints and iconolatry; in the De origine erroris in negocio Eucharistiae ac Missae he strove to show that the Catholic conceptions of the Eucharist and of celebrating the Mass were wrong. Bullinger published a combined edition of these works in 4 ° (Zurich 1539), which was divided into two books, according to themes of the original work.»

The Library of the Finnish nobleman, royal secretary and trustee Henrik Matsson (c. 1540–1617), Terhi Kiiskinen Helsinki: Academia Scientarium Fennica (Finnish Academy of Science), 2003, ISBN 978-9514109447, p. 175 [2]

- ^ Froschauer. De origine erroris, Caput XVI (Chapter 16), p. 70

- ^ The Thousand Faces of the Virgin Mary (1996), George H. Tavard, Liturgical Press ISBN 978-0814659144, p. 109. [3]

- ^ Menzel, Konstantinos (14 April 2014). «Abstaining From Sex Is Part of Fasting». Greek Reporter. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ «Concerning Fasting on Wednesday and Friday». Orthodox Christian Information Center. Accessed 8 October 2010.

- ^ Pianigiani, Ottorino (1907). «Vocabolario etimologico della lingua italiana».

- ^ Giebel, Marion (1984). Augustus. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt. p. 6. ISBN 3499503271.

- ^ Columbus World Travel Guide, 25th ed.

- ^ Reiland, Catherine. «To Heaven Through the Streets of Guatemala City: the Processions of the Virgin of the Assumption». Emisferica. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ «The Assumption of Mary into Heaven, the most revered summer Orthodox Christian feast in Bulgaria». bnr.bg.

- ^ a b c Zirpolo 2018, p. 83.

- ^ Zirpolo 2018, pp. 213–214.

Bibliography[edit]

- Alter, Robert (1997). Genesis: Translation and Commentary. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393070262.

- Arnold, Bill T. (2009). Genesis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521000673.

- Beale, G. K.; Campbell, David (2015). Revelation: A Shorter Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0304707812.

- Boss, Sarah Jane (2000). Empress and Handmaid: On Nature and Gender in the Cult of the Virgin Mary. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0304707812.

- Collinge, William J. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Catholicism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810879799.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). «Assumption of the BVM». The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192802903.

- Duffy, Eamon (1989). What Catholics Believe About Mary. London: Catholic Truth Society.

- Ford, John T. (2006). Saint Mary’s Press Glossary of Theological Terms. Saint Mary’s Press. ISBN 978-0884899037.

- Goldingay, John (2020). Genesis. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1493423972.

- Jenkins, Philip (2015). The Many Faces of Christ. Hachette. ISBN 978-0465061617.

- Kerr, W.N. (2001). «Mary, Assumption of». In Elwell, Walter A. (ed.). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0801020759.

- Miravalle, Mark I. (2006). Introduction to Mary: The Heart of Marian Doctrine and Devotion. Queenship Publishing. ISBN 9781882972067.

- O’Carroll, Michael (2000). Theotokos: A Theological Encyclopedia of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1579104542.

- Shoemaker, Stephen J. (2016). Mary in Early Christian Faith and Devotion. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300217216.

- Shoemaker, Stephen J. (2002). Ancient Traditions of the Virgin Mary’s Dormition and Assumption. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199250752.

- Wagner, David M. (2020). The Church and the Modern Era (1846–2005). Ave Maria Press. ISBN 978-1594717888.

- Warner, Marina (2016). Alone of All Her Sex. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198718789.

- Williams, Paul (2019). «The English Reformers and the Blessed Virgin Mary». In Maunder, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198792550.

- Zirpolo, Lilian H. (2018). Historical Dictionary of Baroque Art and Architecture. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1538111291.

Further reading[edit]

- Duggan, Paul E. (1989). The Assumption Dogma: Some Reactions and Ecumenical Implications in the Thought of English-speaking Theologians. Emerson Press, Cleveland, Ohio.[ISBN missing]

- Hammer, Bonaventure (1909). «Novena 5: for the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary» . Mary, help of Christians. Benziger Brothers.

- Mimouni, Simon Claude (1995). Dormition et assomption de Marie: Histoire des traditions anciennes. Beauchesne, Paris.[ISBN missing]

- Salvador-Gonzalez, José-María (2019). «Musical Resonanes in the Assumption of Mary and Their Reflection in the Italian Trecento and Quattrocento Painting». Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography. 44 (1–2): 79–96. ISSN 1522-7464.

External links[edit]

- «Munificentissimus Deus – Defining the Dogma of the Assumption» Vatican, 1 November 1950

- Footage of the Assumption proclamation (1950) (British Pathé)

- «De Obitu S. Dominae». Uoregon.edu. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- «De Transitu Virginis». Uoregon.edu. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

«Assunta» redirects here. For the hospital in Malaysia, see Assunta Hospital.

| Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary | |

|---|---|

A famous treatment in Western art, Titian’s Assumption, 1516–1518 |

|

| Also called |

|

| Observed by |

|

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | the bodily taking up of Mary, the mother of Jesus into Heaven |

| Observances | Attending Mass or service |

| Date |

|

| Frequency | Annual |

Memorial in Youghal, Ireland, to the promulgation of the dogma of the Assumption

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it in 1950 in his apostolic constitution Munificentissimus Deus as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by God that the immaculate Mother of God, Mary ever virgin, when the course of her earthly life was finished, was taken up body and soul into the glory of heaven.[2]

The declaration was built upon the 1854 dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, which declared that Mary was conceived free from original sin, and both have their foundation in the concept of Mary as the Mother of God.[3] It leaves open the question of whether Mary died or whether she was raised to eternal life without bodily death.[2]

The equivalent belief (but not held as dogma) in the Eastern Orthodox Church is the Dormition of the Mother of God or the «Falling Asleep of the Mother of God».

The word ‘assumption’ derives from the Latin word assūmptiō meaning «taking up».

Traditions relating to the Assumption[edit]

In some versions of the assumption narrative, the assumption is said to have taken place in Ephesus, in the House of the Virgin Mary. This is a much more recent and localized tradition. The earliest traditions say that Mary’s life ended in Jerusalem (see Tomb of the Virgin Mary). By the 7th century, a variation emerged, according to which one of the apostles, often identified as Thomas the Apostle, was not present at the death of Mary but his late arrival precipitates a reopening of Mary’s tomb, which is found to be empty except for her grave clothes. In a later tradition, Mary drops her girdle down to the apostle from heaven as testament to the event.[4] This incident is depicted in many later paintings of the Assumption.

Teaching of the Assumption of Mary became widespread across the Christian world, having been celebrated as early as the 5th century and having been established in the East by Emperor Maurice around AD 600.[5] John Damascene records the following:

St. Juvenal, Bishop of Jerusalem, at the Council of Chalcedon (451), made known to the Emperor Marcian and Pulcheria, who wished to possess the body of the Mother of God, that Mary died in the presence of all the Apostles, but that her tomb, when opened upon the request of St. Thomas, was found empty; wherefrom the Apostles concluded that the body was taken up to heaven.[6]

History[edit]

Some scholars argue that the Dormition and Assumption traditions can be traced early in church history in apocryphal books, with Shoemaker stating,

Other scholars have similarly identified these two apocrypha as particularly early. For instance, Baldi, Masconi, and Cothenet analyzed the corpus of Dormition narratives using a rather different approach, governed primarily by language tradition rather than literary relations, and yet all agree that the Obsequies (i.e., the Liber Requiei) and the Six Books apocryphon reflect the earliest traditions, locating their origins in the second or third century.[7]

Scholars of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum «argued that during or shortly after the apostolic age a group of Jewish Christians in Jerusalem preserved an oral tradition about the end of the Virgin’s life». Thus, by pointing to oral tradition, they argued for the historicity of the assumption and Dormition narratives. However, Shoemaker notes they fail to take into account the various «strikingly diverse traditions» that the Assumption seems to come from, mainly, «a great variety of original types», rather than «a single unified tradition». Regardless, Shoemaker states even those scholars note «belief in the Virgin’s Assumption is the final dogmatic development, rather than the point of origin, of these traditions». [8]

According to Stephen J. Shoemaker, the first known narrative to address the end of Mary’s life and her assumption is the apocryphal third- and possibly second-century, Liber Requiei Mariae («Book of Mary’s Repose»).[9] Shoemaker asserts that «this earliest evidence for the veneration of Mary appears to come from a markedly heterodox theological milieu».[10]

Other early sources, less suspect in their content, also contain the assumption. «The Dormition/Assumption of Mary» (attributed to John the Theologian or «Pseudo-John»), another anonymous narrative, is possibly dated to the fourth century, but is dated by Shoemaker as later.[11] The «Six Books Dormition Apocryphon», dated to the early fourth century,[10] likewise speaks of the Assumption. «Six Books Dormition Apocryphon» was perhaps associated with the Collyridians who were condemned by Epiphanius of Salamis «for their excessive devotion to the Virgin Mary».[10]

Shoemaker mentions that «the ancient narratives are neither clear nor unanimous in either supporting or contradicting the dogma» of the assumption.[12]

In accordance with Stephen J. Shoemaker «there is no evidence of any tradition concerning Mary’s Dormition and Assumption from before the fifth century. The only exception to this is Epiphanius’ unsuccessful attempt to uncover a tradition of the end of Mary’s life towards the end of the fourth century.»[13] The New Testament is silent regarding the end of her life, the early Christians produced no accounts of her death, and in the late 4th century Epiphanius of Salamis wrote he could find no authorized tradition about how her life ended.[14] Nevertheless, although Epiphanius could not decide on the basis of biblical or church tradition whether Mary had died or remained immortal, his indecisive reflections suggest that some difference of opinion on the matter had already arisen in his time,[15] and he identified three beliefs concerning her end: that she died a normal and peaceful death; that she died a martyr; and that she did not die.[15] Even more, in another text Epiphanius stated that Mary was like Elijah because she never died but was assumed like him.[16]

Notable later apocrypha that mention the Assumption include De Obitu S. Dominae and De Transitu Virginis, both probably from the 5th century, with further versions by Dionysius the Areopagite, and Gregory of Tours, among others.[17] The Transitus Mariae was considered as apocrypha in a 6th-century work called Decretum Gelasianum,[18] but by the early 8th century the belief was so well established that John of Damascus could set out what had become the standard Eastern tradition, that «Mary died in the presence of the Apostles, but that her tomb, when opened, upon the request of St Thomas, was found empty; wherefrom the Apostles concluded that the body was taken up to heaven.»[19]

Euthymiac History, from sixth century, contains one of the earliest reference to the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary.[20]

The Feast of the Dormition, imported from the East, arrived in the West in the early 7th century, its name changing to Assumption in some 9th century liturgical calendars.[21] In the same century Pope Leo IV (reigned 847–855) gave the feast a vigil and an octave to solemnise it above all others, and Pope Nicholas I (858–867) placed it on a par with Christmas and Easter, tantamount to declaring Mary’s translation to Heaven as important as the Incarnation and Resurrection of Christ.[21] In the 10th century the German nun Elisabeth of Schönau was reportedly granted visions of Mary and her son which had a profound influence on the Western Church’s tradition that Mary was assumed in body and soul into Heaven,[21] and Pope Benedict XIV (1740–1758) declared it «a probable opinion, which to deny were impious and blasphemous».[22]

Scriptural basis[edit]

The Basilica of the Assumption of Our Lady in Mosta, Malta. The church is also known as Mosta Dome or as Mosta Rotunda. The façade of the basilica is decorated for the Feast of the Assumption, celebrated on 15 August.

Pope Pius, in promulgating Munificentissimus Deus, stated that «All these proofs and considerations of the holy Fathers and the theologians are based upon the Sacred Writings as their ultimate foundation.» The pope did not advance any specific text as proof of the doctrine, but one senior advisor, Father Jugie, expressed the view that Revelation 12:1–2 was the chief scriptural witness to the assumption:[23]

And a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars; and she was with child …

The symbolism of this verse is based on the Old Testament, where the sun, moon, and eleven stars represent the patriarch Jacob, his wife, and eleven of the twelve tribes of Israel, who bow down before the twelfth star and tribe, Joseph, and verses 2–6 reveal that the woman is an image of the faithful community.[24] The possibility that it might be a reference to Mary’s immortality was tentatively proposed by Epiphanius in the 4th century, but while Epiphanius made clear his uncertainty and did not advocate the view, many later scholars did not share his caution and its reading as a representation of Mary became popular with certain Roman Catholic theologians.[25]

Many of the bishops cited Genesis 3:15, in which God is addressing the serpent in the Garden of Eden, as the primary confirmation of Mary’s assumption:[26]

Enmity will I set between you and the woman, between your seed and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church affirms that the account of the fall in Genesis 3 uses figurative language, and that the fall of mankind, by the seductive voice of the snake in the bible, represents the fallen angel, Satan.[27] Similarly, the great dragon in Revelation is a representation of Satan, identified with the serpent from the garden who has enmity with the woman. Though the woman in revelation represents the people of God, faithful Israel and the Church, Mary is considered the Mother of the Church.[28] Therefore, in Catholic thought there is an association between this heavenly woman and Mary’s Assumption.

Some scholars conclude that no messianic prophecy was originally intended,[29] that in the Hebrew Bible the serpent is not satanic, and the verse is simply a record of the enmity between humans and snakes (although a memory of the ancient Canaanite myth of a primordial sea-serpent may stand behind them, albeit at a distance).[30] But although the verse speaks literally about mankind’s relationship with snakes, there is also a metaphorical overtone: a door has been opened to a dark power and there is no promise of victory, but rather a warning of ongoing conflict.[31]

Among the many other passages noted by the pope[which?] were the following:[26]

- Psalm 132:8, greeting the return of the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem («Arise, O Lord, into your resting place, you and the ark which you have sanctified!»), where the ark is taken as the prophetic «type» of Mary;[32]

- Revelation 11:19, in which John sees the ark of the covenant in heaven (this verse immediately precedes the vision of the woman clothed with the sun);

- Luke 1:28, in which the Archangel Gabriel greets Mary with the words, «Hail Mary, full of grace», since Mary’s bodily assumption is a natural consequence of being full of grace;

- 1 Corinthians 15:23 and Matthew 27:52–53, concerning the certainty of bodily resurrection for all who have faith in Christ.

Assumption versus Dormition[edit]

The Dormition: ivory plaque, late 10th-early 11th century (Musée de Cluny)

Some Catholics believe that Mary died before being assumed, but they believe that she was miraculously resurrected before being assumed. Others believe she was assumed bodily into Heaven without first dying.[33][34] Either understanding may be legitimately held by Catholics, with Eastern Catholics observing the Feast as the Dormition.

Many theologians note by way of comparison that in the Catholic Church the Assumption is dogmatically defined, whilst in the Eastern Orthodox tradition the Dormition is less dogmatically than liturgically and mystically defined. Such differences spring from a larger pattern in the two traditions, wherein Catholic teachings are often dogmatically and authoritatively defined – in part because of the more centralized structure of the Catholic Church – whilst in Eastern Orthodoxy many doctrines are less authoritative.[35]

The Latin Catholic Feast of the Assumption is celebrated on 15 August and the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholics celebrate the Dormition of the Mother of God (or Dormition of the Theotokos, the falling asleep of the Mother of God) on the same date, preceded by a 14-day fast period. Eastern Christians believe that Mary died a natural death, that her soul was received by Christ upon death, that her body was resurrected after her death and that she was taken up into heaven bodily in anticipation of the general resurrection.

Orthodox tradition is clear and unwavering in regard to the central point [of the Dormition]: the Holy Virgin underwent, as did her Son, a physical death, but her body – like His – was afterwards raised from the dead and she was taken up into heaven, in her body as well as in her soul. She has passed beyond death and judgement and lives wholly in the Age to Come. The Resurrection of the Body … has in her case been anticipated and is already an accomplished fact. That does not mean, however, that she is dissociated from the rest of humanity and placed in a wholly different category: for we all hope to share one day in that same glory of the Resurrection of the Body that she enjoys even now.[36]

Protestant views[edit]

The Assumption of Mary, Rubens, 1626

Views differ within Protestantism, with those with a theology closer to Catholicism sometimes believing in a bodily assumption whilst most Protestants do not.

Lutheran views[edit]

The Feast of the Assumption of Mary was retained by the Lutheran Church after the Reformation.[37] Evangelical Lutheran Worship designates August 15 as a lesser festival named «Mary, Mother of Our Lord» while the current Lutheran Service Book formally calls it «St. Mary, Mother of our Lord».[37]

Anglican views[edit]

Within Anglican doctrine the Assumption of Mary is either rejected or regarded as adiaphora («a thing indifferent»);[38] it therefore disappeared from Anglican worship in 1549, partially returning in some branches of Anglicanism during the 20th century under different names. A Marian feast on 15 August is celebrated by the Church of England as a non-specific feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a feast called by the Scottish Episcopal Church simply «Mary the Virgin»,[39][40][41] and in the US-based Episcopal Church it is observed as the feast of «Saint Mary the Virgin: Mother of Our Lord Jesus Christ»,[42]

while other Anglican provinces have a feast of the Dormition[39] – the Anglican Church of Canada for instance marks the day as the «Falling Asleep of the Blessed Virgin Mary».[43]

The Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission, which seeks to identify common ground between the two communions, released in 2004 a non-authoritative declaration meant for study and evaluation, the «Seattle Statement»; this «agreed statement» concludes that «the teaching about Mary in the two definitions of the Assumption and the Immaculate Conception, understood within the biblical pattern of the economy of hope and grace, can be said to be consonant with the teaching of the Scriptures and the ancient common traditions».[44]

Other Protestant views[edit]

The Protestant reformer Heinrich Bullinger believed in the assumption of Mary. His 1539 polemical treatise against idolatry[45] expressed his belief that Mary’s sacrosanctum corpus («sacrosanct body») had been assumed into heaven by angels:

|

Hac causa credimus ut Deiparae virginis Mariae purissimum thalamum et spiritus sancti templum, hoc est, sacrosanctum corpus ejus deportatum esse ab angelis in coelum.[46] |

For this reason we believe that the Virgin Mary, Begetter of God, the most pure bed and temple of the Holy Spirit, that is, her most holy body, was carried to heaven by angels.[47] |

Feasts and related fasting period[edit]

Orthodox Christians fast fifteen days prior to the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, including abstinence from sexual relations.[48] Fasting in the Orthodox tradition refers to not consuming a meal until evening.[49]

The Assumption is important to many Christians, especially Catholics and Orthodox, as well as many Lutherans and Anglicans, as the Virgin Mary’s heavenly birthday (the day that Mary was received into Heaven). Belief about her acceptance into the glory of Heaven is seen by some Christians as the symbol of the promise made by Jesus to all enduring Christians that they too will be received into paradise. The Assumption of Mary is symbolised in the Fleur-de-lys Madonna.

The present Italian name of the holiday, Ferragosto, may derive from the Latin name, Feriae Augusti («Holidays of the Emperor Augustus»),[50] since the month of August took its name from the emperor. The feast was introduced by Bishop Cyril of Alexandria in the 5th century. In the course of Christianization, he put it on 15 August. In the middle of August, Augustus celebrated his victories over Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra at Actium and Alexandria with a three-day triumph. The anniversaries and later only 15 August were public holidays from then on throughout the Roman Empire.[51]

The Solemnity of the Assumption on 15 August was celebrated in the Eastern Church from the 6th century. The Western Church adopted this date as a Holy Day of Obligation to commemorate the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a reference to the belief in a real, physical elevation of her sinless soul and incorrupt body into Heaven.

Public holidays[edit]

Patoleo (sweet rice cakes) are the pièce de résistance of the Assumption feast celebration among Goan Catholics.

Assumption Day on 15 August is a nationwide public holiday in Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chile, Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cyprus, East Timor, France, Gabon, Greece, Georgia, Republic of Guinea, Haiti, Italy, Lebanon, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Republic of North Macedonia, Madagascar, Malta, Mauritius, Republic of Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro (Albanian Catholics), Paraguay, Poland (coinciding with Polish Army Day), Portugal, Romania, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Slovenia, Spain, Syria, Tahiti, Togo, and Vanuatu;[52] and was also in Hungary until 1948.

It is also a public holiday in parts of Germany (parts of Bavaria and Saarland) and Switzerland (in 14 of the 26 cantons). In Guatemala, it is observed in Guatemala City and in the town of Santa Maria Nebaj, both of which claim her as their patron saint.[53] Also, this day is combined with Mother’s Day in Costa Rica and parts of Belgium.

Prominent Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox countries in which Assumption Day is an important festival but is not recognized by the state as a public holiday include the Czech Republic, Ireland, Mexico, the Philippines and Russia. In Bulgaria, the Feast of the Assumption is the biggest Eastern Orthodox Christian celebration of the Holy Virgin. Celebrations include liturgies and votive offerings. In Varna, the day is celebrated with a procession of a holy icon, and with concerts and regattas.[54]