«Последний самурай»

Упрощённый сценарий

КАКОЕ-ТО ЗДАНИЕ, АМЕРИКА, 1876 г.

ТОМ КРУЗ надирается в слюни, после чего пытается продать ружье.

ТОМ КРУЗ

Как приверженец технического прогресса, скажу вам, что по сравнению

с этим супермодерновым ружьём марки «Винчестер» всякие

мечи и луки со стрелами сосут не нагибаясь и я, как Настоящий

Тупой Американец, признаю только новые hi-fi-технологии!

ТОНИ ГОЛДУИН

И из-за твоей тупости ты пойдёшь на что угодно, лишь бы загрести

бабла себе в лопатничек. Посему поедешь со мной в Японию для

проведения Курса Молодого Бойца и обучишь аборигенов обращаться

с огнестрельным оружием, чтобы понять всю духовность старинных

традиций. Ну и заодно духовно возродишься. Я тебя ещё не заебал

своими прогонами?

ТОМ КРУЗ

(отрываясь от ведра с виски)

Вроде в учебнике по истории японцев тренировали пруссаки, а не

американцы…

ТОНИ ГОЛДУИН

Том, кто сейчас читает книги? Все в кино ходят, там проще. Нехуй

тут базары разводить, тащи свою задницу в «Боинг»!

ТОМ КРУЗ

А космического корабля у тебя нет? Жаль…

ЯПОНИЯ

ТОМ КРУЗ пытается научить ЯПОНЦЕВ хотя бы правильно держать ружьё, но они оказываются на редкость отстойными солдатами.

ГЛАВНЫЙ ЯПОНСКИЙ ВОЕННЫЙ

Стройся в две шеренги!!! Мы идём войной на ЗВЕРСКИ ХАРИЗМАТИЧНОГО

КЕНА ВАТАНАБЕ, человека с золотым сердцем, чтящего традиции предков.

2.

Начинается БИТВА и новоиспечённые бойцы проигрывают с разгромным счётом. Том расстреливает все патроны в самураев, затем кидает в них револьвером, они уклоняются. Потом он отнимает у мёртвого самурая катану и внезапно обнаруживает в себе недеццкие навыки владения ею. Он убивает нескольких врагов, потом ещё нескольких. Затем приглашённая звезда Хироюки Санада почти отрубает ГОЛОВУ ТОМУ КРУЗУ, но тот уклоняется и убивает противника.

БОГ

Блядь!!!

ТОМА берут в плен и везут в деревню, где все его магические самурайские навыки внезапно исчезают.

КЕН ВАТАНАБЕ

Добро пожаловать в мою деревню, ТОМ. Устраивайся у нас поудобней,

чувствуй себя как дома. Ты полюбишь наш тихий уклад жизни…

Я буду звать тебя «Пляшущий с самураями».

ТОМ учится драться на мечах и постигает японский язык.

ТОМ КРУЗ

КЕН, я полностью пропёрся от стиля вашей жизни, духовности и

дисциплины. А самое главное, я умею махаться на мечах, ими же

так прикольно рубить головы! Научи меня Пути самурая, чтобы я

мог понтоваться перед белой аудиторией, ни хрена не понимающейся

в боях на катанах.

КЕН ВАТАНАБЕ

Вот тебе DVD «Убить Билла» — посмотри и поймёшь всё сущее. Только

помни, что к этом фильму надо относиться серьёзно.

ТОМ КРУЗ

А я уже попкорна купил…

ТОМ и КЕН готовятся к битве с АМЕРИКАНСКОЙ и ЯПОНСКОЙ АРМИЯМИ.

ТОНИ ГОЛДУИН

ТОМ, ты… ты самурай! Что за нахуй?!

3.

ТОМ КРУЗ

По крайней мере я теперь не похож на дублёра Вигго Мортенсена.

Мы будем убивать тебя до смерти, собакоедкий Дудл-Ду!

ТОНИ ГОЛДУИН

ТОМ, иди проспись! Нельзя так упрощать историю человечества!!!

Ты вообще подумал о морали своих поступков???

ТОМ КРУЗ

Да мне насрать с высокой колокольни, кто прав, кто виноват!!!

Я не могу стоять в стороне, когда дело касается японской культуры,

от которой я так фанатею!

ТОНИ ГОЛДУИН

Отлично! А чтобы зрителям не было скучно, то заявляю со всей

ответственностью, что я — наизлобнейший сукин сын!!!

ГЛАВНЫЙ ЯПОНСКИЙ ВОЕННЫЙ — КЕНУ ВАТАНАБЕ

Укуси мой блестящий железный зад!

ВСЕ дерутся. На экране кровь, в муках умирают люди… ЯПОНСКАЯ АРМИЯ умирает с позором, САМУРАИ умирают с честью.

ИМПЕРАТОР

Твоя упертость на Японии впечатлила меня, и я задушу в корне

технический прогресс в припадке очередной смены настроения.

ТОМ КРУЗ

Это большая честь стать Последним Самураем, пережившим всех суперсамураев.

ИМПЕРАТОР

Ну что, все убедились в величии белых людей?

(кланяется)

Да здравствует Голливуд!

КОНЕЦ

Переводчик: Антон Назаров

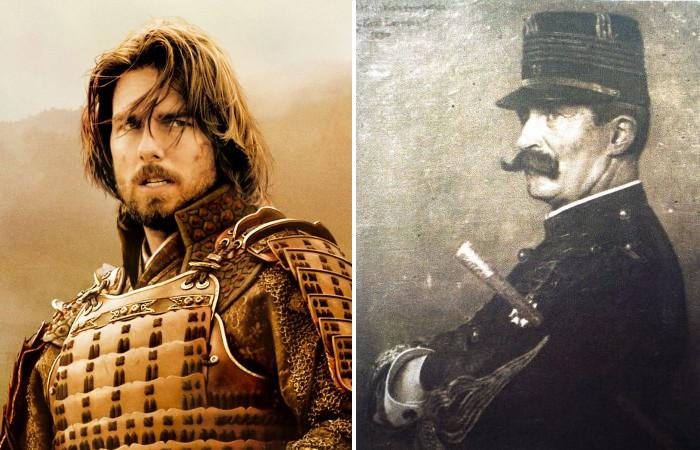

Том Круз в роли самурая и его исторический прототип.

«Последний самурай» — довольно хороший, хотя и недооцененный фильм с Томом Крузом в главной роли. Как и многие другие голливудские эпосы он не является точной правдой, хоть и подается интересным и зрелищным образом. Из обзора можно узнать насколько же сильно перестарались голливудские сценаристы, создавая образ бесстрашного европейца, воевавшего с самураями.

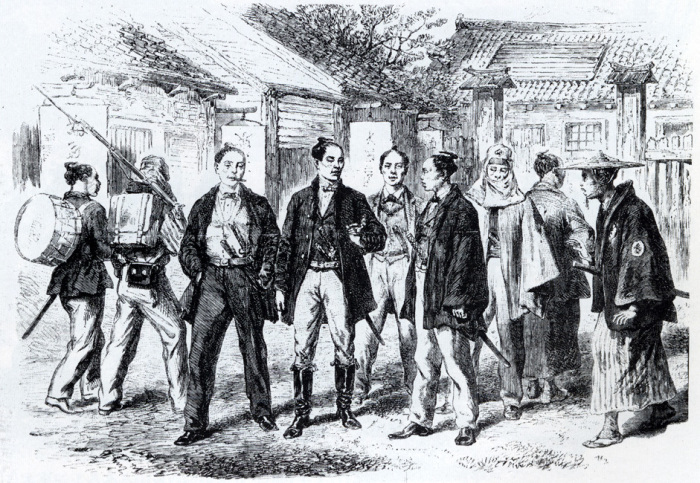

Флот Мэтью Пэрри (США) прибыл к берегам Японии. Фрагмент картины. | Фото: ru.wikipedia.org.

Много веков власти Японии не пускали в страну иностранцев, ведь европейские торговцы привозили с собой оружие и товары со всего мира. Опасаясь развала традиционных ценностей, феодальное правительство, Сёгунат Токугава, изгнало всех иноземцев с островов, оставив для торговли лишь небольшой порт Нагасаки.

Прошло двести лет, прежде чем японцы задумались о своем отставании от остального мира. В 1853 году к японским островам прибыл большой американский флот, состоящий из современных по тем временам паровых кораблей. Под угрозой пушек американцы вынудили Японию подписать договор о мире, дружбе и торговле. Неудивительно, что здравый смысл восторжествовал, когда «средневековые» японцы увидели новейшие военные корабли в своих бухтах. Они открыли торговлю, поощряя культурный обмен, чтобы «догнать» современную эпоху.

Молодой император Мэйдзи (Муцухито). | Фото: ru.wikipedia.org.

Французские военные специалисты перед отправкой в Японию, 1866 год. | Фото: en.wikipedia.org.

События фильма «Последний самурай» охватывают интересное время и место: Японию конца XIX века, эпоху Реставрации Мейдзи. Это был сложный период истории страны, когда феодальная Япония становилась современной монархией по образцу великих европейских держав, произошла политическая, социальная и индустриальная революция. Велась модернизация во всех сферах, в частности эволюция военного дела и снижение политической и военной роли самураев – средневековых рыцарей, сражающихся мечами и луками. Теперь Япония закупала на Западе современное огнестрельное оружие. А для обучения императорской армии нанимались офицеры из самых «опытных» воюющих стран мира – Франции, Великобритании, США.

Том Круз в роли капитана Олгрена. | Фото: blog.gaijinpot.com.

Сражение императорских войск и самураев. Скриншот из игры Total War: Shogun 2 — Fall Of The Samurai. | Фото: gamona.de.

Голливуд упростил сценарий фильма, чтобы показать самураев как простых и хороших людей, а модернизацию Японии как нечто плохое и гнетущее. На самом деле во время Реставрации Мэйдзи происходило перераспределение социальных классов. Новое правительство упразднило касту самураев, правящих жестокой рукой и занимавшихся преимущественно сельским хозяйством. Это и стало причиной мятежа.

В фильме «Последний самурай» в одно целое смешивается несколько восстаний, которые по истории длились в течении многих лет. Вымышленный лидер Кацумото был основан на личности влиятельного Сайго Такамори, лидера последнего бунта.

Битва за гору Табарудзака. Самураи справа, у них огнестрельное оружие, а их офицеры одеты в европейские мундиры. | Фото: ru.wikipedia.org.

Самураи в сценах сражений фильма изображены с развлекательной точки зрения. Первый же бой показывает, как они умело орудуют мечами и луками, чтобы разгромить вооруженную, но неопытную армию императора Мэйдзи.

Солдаты Сёгуната Токугава на марше, 1864 год. | Фото: ru.wikipedia.org.

История, однако, отображает совсем другую сторону. В то время как один из первых бунтов проходил без современного оружия, в остальных восстаниях использовались современные средства ведения войны.

Повстанцы Такамори использовали винтовки и часто носили мундиры западного стиля, и лишь некоторые использовали традиционные самурайские доспехи. У восставших было более 60 артиллерийских орудий, и они их активно применяли.

Руководитель восстания самураев Сайго Такамори со своими офицерами. | Фото: sarkisarslanian04.blogspot.com.

Имперские войска высаживаются в Йокогаме и готовятся идти в поход против восстания Сацума, 1877 год. | Фото: firedirectioncenter.blogspot.com.

Императорская армии последнюю битву при Сирояме, как и в фильме, действительно выиграла из-за превосходящего количества (около 30 тысяч солдат против 300-400 самураев). Последняя самоубийственная атака самураев была такой же символичной, как это представлено в фильме.

Хотя капитан Олгрен кажется вымышленным, чуждым персонажем, он, тем не менее, имеет реальный исторический прототип с поразительно похожими взглядами и поступками.

Жюль Брюне – французский офицер, участник гражданской войны в Японии. | Фото: en.wikipedia.org.

На создание персонажа, которого играет Том Круз, сценаристов вдохновил француз Жюль Брюне (Jules Brunet). В 1867 году его направили обучать японских солдат использовать артиллерию. С началом восстания самураев он мог вернуться во Францию, но остался и в этой гражданской войне сражался на проигравшей стороне за Сёгунат. Он участвовал в славной и эпической последней битве при Хакодате. Параллели между Брюне и Олгреном показывают, что история первого определенно оказала большое влияние на фильм.

Самураи, одетые в западный костюм. | Фото: all-nationz.com.

«Последний самурай» совмещает более десяти лет реальной истории в короткий рассказ, при этом изменяя французского героя на американского. Также значительно изменено количественное соотношение сторон: новое правительств показано «злым и угнетающим». На самом деле оно дало японцам свободу впервые в их истории.

А ведь не зря говорят, что «Восток – дело тонкое». Могут показаться удивительными 10 малоизвестных фактов о самураях, которые умалчивают в литературе и кино.

Понравилась статья? Тогда поддержи нас, жми:

Страницы: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Говорят, Япония создана мечом.

Древние боги обмакнули коралловый меч в океан,

а когда вытащили, четыре идеальные капли упали в море,

и стали японскими островами.

Я говорю, что Японию создала горстка смельчаков,

воинов, согласных отдать свою жизнь…

…за то, что теперь кажется забытым словом:

Честь.

Дамы и господа: Винчестер.

Лидирующее оружие американской армии…

…празднует столетний юбилей вместе с настоящим героем.

Один из самых заслуженных воинов этой страны.

Обладатель почетной медали за храбрость…

…на святой земле Геттисберга.

Сан-Франциско, 1876 год

Он — последний из 7-й кавалерии,

ее триумфальной кампании против самых свирепых индейских племен.

Дамы и господа, представляю вам…

…капитана Нэйтана Олгрена!

Капитан Нэйтан Олгрен!

Да!

Да!

Один момент, дамы и господа.

Проклятье, Олгрен, твой выход!

Твое последнее представление! Ты уволен! На выход!

Давай! Я устал от этого!

Давай!

Да!

Благодарю, мистер Маккейб, вы слишком добры.

Это, дамы и господа,

ружье, завоевывающее Запад.

Много раз я оказывался…

…в окружении толпы…

…злых врагов…

…лишь с этим ружьем…

…между мной и неминуемой, ужасной смертью.

И, скажу вам, народ, краснокожий —

грозный враг.

И если бы он победил,

мой скальп давно был бы снят,

и перед вами сегодня стоял бы человек с большой лысиной.

Как те жалкие ублюдки…

…на Литтл-Бигхорн.

Голые тела…

…изуродованные.

Оставлены гнить на солнце.

Это, дамы и господа, винтовка 73 года.

Траппер.

Семизарядная. Точно бьет на 360 м, выстрел в секунду.

Сынок, ты когда-нибудь видел, что эта штука делает с людьми?

Она пробила бы в груди твоего отца 15-сантиметровую дыру.

Это правда, дамочка.

Такая красотка.

Можно убить 5, 6, 7 смельчаков без перезарядки.

Обратите внимание, как легко взводится курок.

Благодарю от имени всех, кто умер…

…ради улучшения механических развлечений…

…и коммерческих возможностей.

Мистер Маккейб примет ваши заказы здесь.

Благослови вас Бог.

Должен сказать, капитан, у вас талант к мелодраме.

— Ты жив.

— Точно.

Кастер сказал мне: «Мы отправляемся в Литтл-Бигхорн».

Я говорю: «Почему это «мы»? Это мой счастливый билет.

У меня девять жизней. И еще кое-что.

У меня есть хорошая работа для нас обоих.

Похоже, скоро она тебе понадобится.

Какая работа?

Единственная, на которую ты годишься. Мужская работа.

Если, конечно, ты не собираешься сделать карьеру в театре.

Нэйтан!

Просто выслушай, что он тебе скажет.

Давно не виделись. Рад тебя видеть.

Хочу представить тебе мистера Омуру из Японии…

…и его помощника, чье имя я уже бросил попытки выговорить.

Прошу садиться.

Виски.

Итак, Япония задумала стать цивилизованной страной.

Мистер Омура хочет всеми средствами…

…нанять белых

Страницы: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Здравствуйте уважаемые.

У нас тут какая то японская неделя вырисовывается. Много материалов по Стране Восходящего Ростка опубликовал подряд. Так просто случайно вышло

Вот в этом и парадокс.

Мое японофильство не имеет какой-то серьезной академической или культурной основы — я не читаю катакану, не говорю и не понимаю по-японски. По сути — я воссторженный дилетант. Но дилетант интересующеся и пытающейся разобраться не только во внешних проявлениях того или иного явления, но и постичь его основу

Фильм этот я смотрел неоднократно, очень его люблю, считаю умным, стильным, красивым и чуть ли не лучшей работой Тома Круза. Да и вообще актеры там классные — Хираюки Санада, Масато Харада, Тимоти Сполл, и, конечно же, Кэн Ватанабэ. Плюс классная музыка любимца Ханса Циммера, отличная операторская работа и вообще хороший подход. Очень достойная картина- кто не видел — советую.

Но при всем этом, это исключительно развлекательное и художественное произведение (именно что хорошее кино), а те, кто «на серьезных щщах» пытаются рассуждать хоть о какой-то историчности — вызывают только улыбку. Там есть только околоисторическая канва, но нет ничего реального. Это полностью придуманный мир, не имеющий почти ничего с реальностью. Скажу больше — в фильме вообще нет ни одного исторического персонажа. Как???-возмутятся некоторые внимательные ценители фильма — а император????

Да он тоже ненастоящий

И так во всем фильме

Понятно, для чего это сделано и зачем. Но, повторюсь, говорить об историчности смешно. Это художественное произведение с небольшими элементами исторического повествования.

Поэтому давайте обратим внимание просто именно на эти некоторые небольшие элементы, какие-то кусочки. И надеюсь, вам будет интересно.

Раз начали говорить о главных героях, то давайте продолжим.

В центре повествования героя Тома Круза по имени Нейтан Олгрен. Мы знаем, что он бывший капитан Армии Союза, который зарабатывает на жизнь рекламой и продажей ружей фирмы «Винчестер» и сильно пьет, пытаясь найти покой и забыть ужасы рейдов по индейским деревням.

Однополчанин, старый и надежный сержант Зеб отводит его на встречу с японцами и полковником Багли (отличная роль Тони Голдуина), бывшим командиром Олгрена. Глава делегации министр Омура предлагает Олгрену обучать японскую армию, и тот, после некоторых сомнений, соглашается.

Тут все конечно смешно. От начала до конца. Почему? Ну,смотрите. Первое — в армии Союза професиональных военных было меньшинство. Зачастую, даже звание полковника присваивалось вовсе не за воинские достижения, а за что-то иное (вспомним создателя KFC хотя бы). Капитан в той армии — командир роты. Сержант и непонятный капитан приходят на встречу с министром другой страны, дабы нанятся на службу? Серьезно? Пусть даже за них хлопочет «целый полковник» :-)))))

Ну а главное, а почему министр Японии решил нанять американцев? Им как-то симпатизировали? Думаю, что после «Чёрных кораблей коммодора Перри» как то не очень

Хотя, как не парадоксально, образ Нейтан Олгрена имеет под собой некоторую историческую основу. Был в Японии такой французский офицер Жюль Брюне (Jules Brunet). В 1867 году его направили обучать японских солдат использовать артиллерию. И он участвовал в Войне Босин на стороне Республики Эдзо, сиречь за Сёгунат. После поражении от императорской армии в Битве при Хакодате Жюль Брюне бежал в Иокогаму, а затем вернулся во Францию. Но война Босин это совсем не то, что показано в фильме. Но все же, все же…

Жюль Брюне

Конечно же всеобщее внимание приковано к Морицугу Кацумото. Благородный и умный человек, который восстает против своего императора, которому еще недавно помог вернуть реальную власть не потому, что считает себя обделенным, и даже не потому, что хочет встать на пути промышленного прогресса, пытаясь удержаться за отжившие традиции, а затем что хочет своей жизнью показать, что в этих традициях сердце и душа страны, и процветание произойдет только тогда, когда современные веяния будут сочитаться с лучшими проявлениями национальных основ.

Понятно, что авторы создавая образ Кацумото, блистательно сыгранный Кэном Ватанабэ, вдохновлялись биографией одного из великих героев японской нации маршала Сайго Такамори.

Сайго Такамори

Этот сацумский самурай всей душой и сердцем поддержал микадо, быстро выбился в лидеры императорской армии во время Войны Босин и окончательно сокрушил Сёгунат.

Вознесся на самый зенит власти, но не был согласен с неколторыми постулатами политики модернизации Японии и свободной торговли с западными странами. Возглавил Сацумское восстание, которое потерпело поражение, а сам Сайго и после Битвы при Сирояме, которую отчасти попытались восстановить в последних сценах фильма, окончательно был разбит и покончил жизнь самоубийством, совершив сэппуку. Но император после смерти его помиловал и возвысил. А в памяти народной Сайго остался великим героем.

Хотя Сайго и Кацумото совсем разные были, но аллюзии и параллели понятны и сделаны неплохо

А вот министра Омура (отличная роль Масато Харада) тут показан главным отрицательным героем. Этакий хитрован, макиавельевского типа, который готов поступиться честью, ради результата. Правда результат этот — величие своей страны. Просто он видит ее именно так, а романтики типа Кацумото мешает ему реализовывать свое видение. Этакий акунин, по определению Григория Шалвовича Чхартишвили

Но это странно, конечно. Ибо тут за основу взят «отец Японской армии» маршал императорской армии гэнро Ямагата Аритомо. В разные года премьер-министр Японии, председатель Генерального штаба армии, Министр армии, министр внутренних дел, министр юстиции, председатель Тайного совета. Да, этот знаток японской поэзии и японского садоводства добился публикации указа о введении этой повинности, отменив тем самым традиционные самурайские войска и даже лично разбил Сайго в сражении при Сирояме (24 сентября 1877 года), но никакой личной ненависти или неприятия к Сайго Такамори не испытывал вовсе.

Даже наоборот. Но в кино нужно было сделать противника и олицетворение всего того, с чем боролся Кацумото, и это сделали из Омуры

От фигур главных героев давайте перейдем к другим элементам.

Наверное, вам хочется разобрать подробно атаку ниндзя на деревню Кацумото, но я думаю, делать этого не стоит. Если вам интересно — у меня было несколько постов по оружию синоби (именно так чаще всего в Японии называют ниндзя). Посмотреть можно тут: https://id77.livejournal.com/659162.html(добраться до первой по гиперссылкам)

Почему не стоит? Ну, потому что если бы какие то синоби клана Ига к этому времени еще существовали, то налет на деревню буси — это вверх идиотизма. И стоило бы кучу денег. Синоби классный и высокопрофесиональный шпион, могущий осуществить и некоторые «мокрые дела», но стоящий очень дорого. А уж бросать отряд ниндзя на кучу самураев -это как забивать гвозди микроскопом….

А вот момент, когда герой Тома Круза впервые попадает в Японию очень даже понравился — прекрасно показывает начавшиеся активные преобразование того времени. Понятно, что это Сеттльмент Иокогамы, но это сочитание конных экипажей и ркиш, мужчин, облаченных в модные костюмы и котелки и двигующихся между ними людей в юката, вполне соответствует тому, что происходило в те годы — страна активно двигалась к модернизации. Художник по костюмам отлично отработал.

А вот сцена с отрезанием волос у самурая не понравилась совсем. Опять-таки, повторюсь, понятно почему и зачем она в художественной картине. Но по сути и логике….

Указ о причёсках и мечах — закон Японии, отменивший сословные отличия, разрешив жителям страны свободно выбирать причёски и не носить мечи был провозглашён 23 сентября 1871 года.

Но чтобы такой беспредел устраивать, да еще и на улице….. Нет уж, увольте :-))) Этим занималась полиция, в основе которой были или ёрики (потомственные служители закона) или те же самураи. Ни тем ни другим и в голову не пришло бы нарываться так на улице и пытаться лишить чести самурая, ибо…..:-) А вообще в той Японии волосы — один из важнейших компонентов красоты» и «отрезание волос — это как отречение от былого уклада жизни. Нужно было подойти к этому сознательно.

Ну и пару слов стоит сказать об униформе. Тут все сделано достойно. Не без переборов некоторых, но очень даже хорошо. Униформисты и реконструкторы сделали свое дело. на традиционных доспехах концентрироваться не будем — уже говорили не раз и вспомним еще.

А вот на униформе армии стоит остановится.

Ибо по форме видна динамика не только перевооружения и создание армии (от новобранцев, которых обучал Олгрен),

до артиллеристов, которые управляются с картечницами Гэтлинга.

Немного косякнули только в моменте отрицания волос самурая. Ошиблись лет так на 15 :-))

А так в целом по форме — молодцы! Интересно было посмотреть

Ну и под конец эпическая атака… Красиво

Вот примерно так. Надеюсь, вам было интересно

Приятного времени суток.

«Последний самурай» – довольно хороший, хотя и недооцененный фильм с Томом Крузом в главной роли. Как и многие другие голливудские эпосы он не является точной правдой, хоть и подается интересным и зрелищным образом. Из обзора можно узнать насколько же сильно перестарались голливудские сценаристы, создавая образ бесстрашного европейца, воевавшего с самураями.

Флот Мэтью Пэрри (США) прибыл к берегам Японии. Фрагмент картины.

Много веков власти Японии не пускали в страну иностранцев, ведь европейские торговцы привозили с собой оружие и товары со всего мира. Опасаясь развала традиционных ценностей, феодальное правительство, Сёгунат Токугава, изгнало всех иноземцев с островов, оставив для торговли лишь небольшой порт Нагасаки.

Прошло двести лет, прежде чем японцы задумались о своем отставании от остального мира. В 1853 году к японским островам прибыл большой американский флот, состоящий из современных по тем временам паровых кораблей. Под угрозой пушек американцы вынудили Японию подписать договор о мире, дружбе и торговле. Неудивительно, что здравый смысл восторжествовал, когда «средневековые» японцы увидели новейшие военные корабли в своих бухтах. Они открыли торговлю, поощряя культурный обмен, чтобы «догнать» современную эпоху.

Молодой император Мэйдзи (Муцухито).

Французские военные специалисты перед отправкой в Японию, 1866 год.

События фильма «Последний самурай» охватывают интересное время и место: Японию конца XIX века, эпоху Реставрации Мейдзи. Это был сложный период истории страны, когда феодальная Япония становилась современной монархией по образцу великих европейских держав, произошла политическая, социальная и индустриальная революция. Велась модернизация во всех сферах, в частности эволюция военного дела и снижение политической и военной роли самураев – средневековых рыцарей, сражающихся мечами и луками. Теперь Япония закупала на Западе современное огнестрельное оружие. А для обучения императорской армии нанимались офицеры из самых «опытных» воюющих стран мира – Франции, Великобритании, США.

Том Круз в роли капитана Олгрена.

Сражение императорских войск и самураев. Скриншот из игры Total War: Shogun 2 – Fall Of The Samurai.

Голливуд упростил сценарий фильма, чтобы показать самураев как простых и хороших людей, а модернизацию Японии как нечто плохое и гнетущее. На самом деле во время Реставрации Мэйдзи происходило перераспределение социальных классов. Новое правительство упразднило касту самураев, правящих жестокой рукой и занимавшихся преимущественно сельским хозяйством. Это и стало причиной мятежа.

В фильме «Последний самурай» в одно целое смешивается несколько восстаний, которые по истории длились в течении многих лет. Вымышленный лидер Кацумото был основан на личности влиятельного Сайго Такамори, лидера последнего бунта.

Битва за гору Табарудзака. Самураи справа, у них огнестрельное оружие, а их офицеры одеты в европейские мундиры.

Самураи в сценах сражений фильма изображены с развлекательной точки зрения. Первый же бой показывает, как они умело орудуют мечами и луками, чтобы разгромить вооруженную, но неопытную армию императора Мэйдзи.

Солдаты Сёгуната Токугава на марше, 1864 год.

История, однако, отображает совсем другую сторону. В то время как один из первых бунтов проходил без современного оружия, в остальных восстаниях использовались современные средства ведения войны.

Повстанцы Такамори использовали винтовки и часто носили мундиры западного стиля, и лишь некоторые использовали традиционные самурайские доспехи. У восставших было более 60 артиллерийских орудий, и они их активно применяли.

Руководитель восстания самураев Сайго Такамори со своими офицерами.

Имперские войска высаживаются в Йокогаме и готовятся идти в поход против восстания Сацума, 1877 год.

Императорская армии последнюю битву при Сирояме, как и в фильме, действительно выиграла из-за превосходящего количества (около 30 тысяч солдат против 300-400 самураев). Последняя самоубийственная атака самураев была такой же символичной, как это представлено в фильме.

Хотя капитан Олгрен кажется вымышленным, чуждым персонажем, он, тем не менее, имеет реальный исторический прототип с поразительно похожими взглядами и поступками.

Жюль Брюне – французский офицер, участник гражданской войны в Японии.

На создание персонажа, которого играет Том Круз, сценаристов вдохновил француз Жюль Брюне (Jules Brunet). В 1867 году его направили обучать японских солдат использовать артиллерию. С началом восстания самураев он мог вернуться во Францию, но остался и в этой гражданской войне сражался на проигравшей стороне за Сёгунат. Он участвовал в славной и эпической последней битве при Хакодате. Параллели между Брюне и Олгреном показывают, что история первого определенно оказала большое влияние на фильм.

«Последний самурай» совмещает более десяти лет реальной истории в короткий рассказ, при этом изменяя французского героя на американского. Также значительно изменено количественное соотношение сторон: новое правительств показано «злым и угнетающим». На самом деле оно дало японцам свободу впервые в их истории.

Оригинал записи и комментарии на LiveInternet.ru

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Last Samurai | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Edward Zwick |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | John Logan |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John Toll |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Hans Zimmer |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

154 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $140 million[3] |

| Box office | $456.8 million[3] |

The Last Samurai is a 2003 epic period action drama film directed and co-produced by Edward Zwick, who also co-wrote the screenplay with John Logan and Marshall Herskovitz from a story devised by Logan. The film stars Ken Watanabe in the title role, with Tom Cruise, who also co-produced, as a soldier-turned-samurai who befriends him, and Timothy Spall, Billy Connolly, Tony Goldwyn, Hiroyuki Sanada, Koyuki, and Shin Koyamada in supporting roles.

Tom Cruise portrays an American captain of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, whose personal and emotional conflicts bring him into contact with samurai warriors in the wake of the Meiji Restoration in 19th century Japan. The film’s plot was inspired by the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion led by Saigō Takamori, and the Westernization of Japan by foreign powers, though in the film the United States is portrayed as the primary force behind the push for Westernization. It is also influenced by the stories of Jules Brunet, a French Imperial Guard sub-lieutenant who fought alongside Enomoto Takeaki in the earlier Boshin War; Philip Kearny, a United States Army (Union Army) major general and French Imperial Guard soldier, notable for his leadership in the American Civil War, who fought against the Tututni tribe in the Rogue River Wars in Oregon; and, to a lesser extent, by Frederick Townsend Ward, an American mercenary who helped Westernize the Chinese army by forming the Ever Victorious Army.

The Last Samurai grossed a total of $456 million[3] at the box office and received positive reviews, with praise for the acting, visuals and Zimmer’s score but criticism for some of its portrayals. It was nominated for several awards, including four Academy Awards, three Golden Globe Awards, and two National Board of Review Awards.

Plot[edit]

In 1876, former U.S. Army Captain Nathan Algren, a skilled soldier who has become a bitter alcoholic traumatized by the atrocities he committed during the American Indian Wars, is approached by his former commanding officer Colonel Bagley. Bagley asks him to train the newly created Imperial Japanese Army for a Japanese businessman, Omura, who intends to use the army to suppress a Samurai-headed rebellion against Japan’s new emperor. Despite his hatred of Bagley, the impoverished Algren takes the job for the money. He is accompanied to Japan by his old friend, Sergeant Zebulon Gant. Upon arriving, Algren meets Simon Graham, a British translator knowledgeable about the samurai.

Algren learns that the Imperial soldiers are simply conscripted peasants with shoddy training and little discipline. While training them to shoot, Algren is informed that the samurai are attacking one of Omura’s railroads; Omura sends the army there, despite Algren’s protests that they are not ready. The battle is a disaster, as the undisciplined conscripts are routed, and Gant is killed. Algren fights to the last before he is surrounded; expecting to die, he is taken prisoner when samurai leader Katsumoto decides to spare him. Algren is taken to Katsumoto’s village. While he is poorly treated at first, he eventually gains the samurai’s respect and grows close to Katsumoto. Algren overcomes his alcoholism and guilt, learns the Japanese language and culture, and is trained in the art of kenjutsu. He develops sympathy for the samurai, who are upset that the pace of modern technology has eroded the traditions of their society. Algren and Taka, Katsumoto’s sister and the widow of a samurai killed by Algren, develop an unspoken affection for each other.

One night, a group of ninja infiltrate the village and attempt to assassinate Katsumoto. Algren saves Katsumoto’s life, and then helps defend the village, concluding that Omura must have hired the ninjas. Katsumoto requests a meeting with Emperor Meiji in Tokyo. He brings Algren, intending to release him. Upon arriving in Tokyo, Algren sees that the Imperial Army has become a well-trained and fully equipped force led by Bagley. Katsumoto, to his dismay, discovers that the young and inexperienced Emperor has become a puppet of Omura. At a government meeting, Omura orders Katsumoto’s arrest for carrying a sword in public and tells him to perform seppuku the next day to redeem his honor. Meanwhile, Algren refuses Bagley’s offer to resume command of the army, prompting Omura to send assassins after him, but Algren kills the assailants and then assists the samurai in freeing Katsumoto. During the rescue, Katsumoto’s son Nobutada is mortally wounded, his sacrifice allowing the others to escape.

As the Imperial Army marches to crush the rebellion, a grieving Katsumoto contemplates seppuku. Algren convinces him to fight and joins the samurai in battle. The samurai use the Imperial Army’s overconfidence to lure them into a trap; the ensuing battle inflicts massive casualties on both sides and forces the Imperial soldiers to retreat. Knowing that Imperial reinforcements are coming, and defeat is inevitable, Katsumoto orders a suicidal cavalry charge on horseback. The samurai withstand an artillery barrage and break through Bagley’s line. Algren kills Bagley, but the samurai are quickly mowed down by Gatling guns. The Imperial captain, previously trained by Algren and horrified by the sight of the dying samurai, orders the soldiers to cease fire, outraging Omura. Katsumoto, mortally wounded, commits seppuku with Algren’s help as the soldiers at the scene kneel in respect.

Later, as trade negotiations conclude, the injured Algren interrupts the proceedings. He presents the Emperor with Katsumoto’s sword and asks him to remember the traditions for which Katsumoto and his fellow Samurai fought and died. The Emperor realizes that while Japan should modernize, it cannot forget its own culture and history. He rejects the trade offer, and when Omura protests, the Emperor threatens to seize Omura’s assets and distribute them among the populace. Omura claims to be disgraced, and the Emperor offers him Katsumoto’s sword, saying that if the shame is too great, Omura should commit seppuku. Omura relents and leaves.

While various rumours regarding Algren’s fate circulate, Graham concludes that Algren had returned to the village to reunite with Taka.

Cast[edit]

- Tom Cruise as Captain Nathan Algren, a Civil War and Indian War veteran haunted by his role in the massacre of Native Americans at the Washita River. Following his discharge from the United States Army, he agrees to help the new Meiji Restoration government train its first Western-style conscript army for a significant sum of money. During the army’s first battle he is captured by the samurai Katsumoto and taken to the village of Katsumoto’s son, where he soon becomes intrigued with the way of the samurai and decides to join them in their cause. His journal entries reveal his impressions about traditional Japanese culture, which almost immediately evolve into unrestrained admiration.

- Ken Watanabe as Lord Moritsugu Katsumoto, the eponymous «Last Samurai,» a former daimyo who was once Emperor Meiji’s most trusted teacher. His displeasure with the influence of Omura and other Western reformers on the Emperor lead him to organize his fellow samurai in a revolt, which he hopes will convince the government not to destroy the samurai’s place in Japanese society. Katsumoto is based on real-life samurai Saigō Takamori, who led the Satsuma Rebellion.

- Koyuki Kato as Taka, widow of a samurai slain by Nathan Algren and younger sister of Lord Katsumoto. She and Algren develop feelings for each other, and she gives him her husband’s armor to wear in the final battle of the rebellion.

- Shin Koyamada as Nobutada Katsumoto, Katsumoto’s son who is responsible for the village where Algren is sent. Nobutada befriends Algren when Katsumoto assigns him to teach Algren Japanese culture and the Japanese language. He dies when he willingly chooses to distract Imperial troops so his father can escape their custody.

- Tony Goldwyn as Colonel Bagley, Nathan Algren’s former commanding officer in the 7th Cavalry Regiment, who hires him to serve as a training instructor for the Imperial Army despite Algren’s hatred of Bagley for his role in the Washita River massacre. In contrast to Algren, Bagley is arrogant and dismissive of the samurai, at one point referring to them nothing more than «savages with bows and arrows». He is killed by Algren who throws a sword into his chest when Bagley tries to shoot Katsumoto in the final battle.

- Masato Harada as Matsue Omura, an industrialist and pro-reform politician. He quickly imports Westernization and modernization while making money for himself through his ownership of Japan’s railroads. Coming from a merchant family, a social class repressed during the days of Shogun rule, Omura openly expresses his contempt for the samurai and takes advantage of Emperor Meiji’s youth to become his chief advisor, persuading him to form a Western-style army for the sole purpose of wiping out Katsumoto and his rebels while ignoring their grievances. His appearance is designed to evoke the image of Okubo Toshimichi, a leading reformer during the Meiji Restoration. Harada noted that he was deeply interested in joining the film after witnessing the construction of Emperor Meiji’s conference room on sound stage 19 (where Humphrey Bogart had once acted) at Warner Brothers studios.[citation needed]

- Shichinosuke Nakamura as Emperor Meiji. Credited with the implementation of the Meiji reforms to Japanese society, the Emperor is eager to import Western ideas and practices to modernize and empower Japan to become a strong nation. However, his inexperience causes him to rely heavily on the advice of men like Omura, who have their own agendas. His appearance bears a strong resemblance to Emperor Meiji during the 1860s (when his authority as Emperor was not yet firmly established) rather than during the 1870s, when the film takes place.

- Hiroyuki Sanada as Ujio, a master swordsman and one of Katsumoto’s most trusted followers. He teaches Algren the art of sword fighting, coming to respect him as an equal. He is one of the last samurai to die in the final battle, being gunned down during Katsumoto’s charge.

- Timothy Spall as Simon Graham, a British photographer and scholar hired as an interpreter for Captain Algren and his non-English speaking soldiers. Initially portrayed as a friendly yet mission-oriented and practical-minded companion, he later comes to sympathize with the samurai cause and helps Algren rescue Katsumoto from Imperial soldiers.

- Seizo Fukumoto as Silent Samurai, an elderly samurai tasked with monitoring Algren during his time in the village, who calls the samurai «Bob». «Bob» ultimately saves Algren’s life (and speaking for the first and only time, «Algren-san!») by taking a bullet meant for him in the final battle.

- Billy Connolly as Sergeant Zebulon Gant, an Irish American Civil War veteran who served with and is loyal to Algren, persuading him to come to Japan and working with him to train the Imperial Army. During the first battle, he is killed by Hirotaro (Taka’s husband) after being wounded with a spear.

- Shun Sugata as Nakao, a tall samurai who wields a naginata and is skilled in jujutsu. He assists Algren in rescuing Katsumoto and dies along with the other samurai in the final battle.

Production[edit]

Filming took place in New Zealand, mostly in the Taranaki region,[4] with mostly Japanese cast members and an American production crew. This location was chosen due to the fact that Egmont/Mount Taranaki resembles Mount Fuji, and also because there is a lot of forest and farmland in the Taranaki region. American Location Manager Charlie Harrington saw the mountain in a travel book and encouraged the producers to send him to Taranaki to scout the locations. This acted as a backdrop for many scenes, as opposed to the built up cities of Japan. Several of the village scenes were shot on the Warner Bros. Studios backlot in Burbank, California. Some scenes were shot in Kyoto and Himeji, Japan. There were 13 filming locations altogether. Tom Cruise did his own stunts for the film.

The film is based on an original screenplay entitled «The Last Samurai», from a story by John Logan. The project itself was inspired by writer and director Vincent Ward. Ward became executive producer on the film – working in development on it for nearly four years and after approaching several directors (Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Weir), until he became interested with Edward Zwick. The film production went ahead with Zwick and was shot in Ward’s native New Zealand.

The film was based on the stories of Jules Brunet, a French Imperial Guard sub-lieutenant who fought alongside Enomoto Takeaki in the earlier Boshin War; Philip Kearny, a United States Army (Union Army) and French Imperial Guard soldier, notable for his leadership in the American Civil War, who fought against the Tututni tribe in the Rogue River Wars in Oregon; and Frederick Townsend Ward, an American mercenary who helped Westernize the Qing army by forming the Ever Victorious Army. The historical roles of other European nations who were involved in the westernization of Japan are largely attributed to the United States in the film, although the film references European involvement as well.

Music[edit]

| The Last Samurai: Original Motion Picture Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Film score by

Hans Zimmer |

|||

| Released | November 25, 2003 | ||

| Genre | Soundtrack | ||

| Length | 59:41 | ||

| Label | Warner Sunset | ||

| Producer | Hans Zimmer | ||

| Hans Zimmer chronology | |||

|

The Last Samurai: Original Motion Picture Score was released on November 25, 2003, by Warner Sunset Records.[5] All music on the soundtrack was composed, arranged, and produced by Hans Zimmer, performed by the Hollywood Studio Symphony, and conducted by Blake Neely.[6] It peaked at number 24 on the US Top Soundtracks chart.[6]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

The film achieved higher box office receipts in Japan than in the United States.[7] Critical reception in Japan was generally positive.[8] Tomomi Katsuta of The Mainichi Shinbun thought that the film was «a vast improvement over previous American attempts to portray Japan», noting that director Edward Zwick «had researched Japanese history, cast well-known Japanese actors and consulted dialogue coaches to make sure he didn’t confuse the casual and formal categories of Japanese speech.» Katsuta still found fault with the film’s idealistic, «storybook» portrayal of the samurai, stating: «Our image of samurai is that they were more corrupt.» As such, he said, the noble samurai leader Katsumoto «set my teeth on edge.»[9]

In the United States, review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 66% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 223 reviews, with an average score of 6.40/10. The site’s consensus states: «With high production values and thrilling battle scenes, The Last Samurai is a satisfying epic.»[10] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted mean rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film received an average score of 55, based on reviews from 43 critics, indicating «mixed or average reviews».[11]

Roger Ebert of Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three and a half stars out of four, saying «beautifully designed, intelligently written, acted with conviction, it’s an uncommonly thoughtful epic.»[12]

One online analyst compares the movie favorably to Dances with Wolves in that each protagonist meets and combats a «technologically backward people». Both Costner’s and Cruise’s characters have suffered through a series of traumatic and brutal battles. Each ultimately uses his experiences to later assist his new friends. Each comes to respect his newly adopted culture. Each even fights with his new community against the people and traditions from which he came.[13]

Box office[edit]

As of January 1, 2016, the film had grossed $456.8 million against a production budget of $140 million. It grossed $111,127,263 in the United States and Canada, and $345,631,718 in other countries.[14] It was one of the most successful box office hits in Japan,[15] where it grossed ¥13.7 billion ($132 million).,[16]

Accolades[edit]

| Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[17] | Best Supporting Actor | Ken Watanabe | Nominated |

| Best Art Direction | Lilly Kilvert and Gretchen Rau | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Ngila Dickson | Nominated | |

| Best Sound Mixing | Andy Nelson, Anna Behlmer and Jeff Wexler | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama | Tom Cruise | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ken Watanabe | Nominated | |

| Best Score | Hans Zimmer | Nominated | |

| National Board of Review | Top Ten Films | 2nd place | |

| Best Director | Edward Zwick | Won | |

| Satellite Awards | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Actor | Tom Cruise | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ken Watanabe | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Hans Zimmer | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | John Toll | Won | |

| Best Art Direction and Production Design | Lilly Kilvert and Gretchen Rau | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Ngila Dickson | Won | |

| Best Editing | Victor Du Bois and Steven Rosenblum | Won | |

| Best Sound | Andy Nelson, Anna Behlmer and Jeff Wexler | Nominated | |

| Best Visual Effects | Nominated | ||

| Visual Effects Society Awards | Outstanding Supporting Visual Effects | Jeffrey A. Okun, Thomas Boland, Bill Mesa, Ray McIntyre Jr. | Won |

| Japan Academy Film Prize | Outstanding Foreign Language Film | Won | |

| Taurus World Stunt Awards | Best Fire Stunt | Won |

Criticism and debate[edit]

The Seikanron debate of 1873. Saigō Takamori insisted that Japan should go to war with Korea.

Motoko Rich of The New York Times observed that the film has opened up a debate, «particularly among Asian-Americans and Japanese,» about whether the film and others like it were «racist, naïve, well-intentioned, accurate – or all of the above.»[9]

Todd McCarthy, a film critic for the Variety magazine, wrote: «Clearly enamored of the culture it examines while resolutely remaining an outsider’s romanticization of it, yarn is disappointingly content to recycle familiar attitudes about the nobility of ancient cultures, Western despoilment of them, liberal historical guilt, the unrestrainable greed of capitalists and the irreducible primacy of Hollywood movie stars.»[18]

According to the history professor Cathy Schultz, «Many samurai fought Meiji modernization not for altruistic reasons but because it challenged their status as the privileged warrior caste. Meiji reformers proposed the radical idea that all men essentially being equal…. The film also misses the historical reality that many Meiji policy advisors were former samurai, who had voluntarily given up their traditional privileges to follow a course they believed would strengthen Japan.»[19]

The fictional character of Katsumoto bears a striking resemblance to the historical figure of Saigō Takamori, a hero of the Meiji Restoration and the leader of the ineffective Satsuma Rebellion, who appears in the histories and legends of modern Japan as a hero against the corruption, extravagance, and unprincipled politics of his contemporaries. «Though he had agreed to become a member of the new government,» wrote the translator and historian Ivan Morris, «it was clear from his writings and statements that he believed the ideals of the civil war were being vitiated. He was opposed to the excessively rapid changes in Japanese society and was particularly disturbed by the shabby treatment of the warrior class.» Suspicious of the new bureaucracy, he wanted power to remain in the hands of the samurai class and the Emperor, and for those reasons, he had joined the central government. «Edicts like the interdiction against carrying swords and wearing the traditional topknot seemed like a series of gratuitous provocations; and, though Saigō realized that Japan needed an effective standing army to resist pressure from the West, he could not countenance the social implications of the military reforms. For this reason Saigō, although participating in the Okinoerabu government, continued to exercise a powerful appeal among disgruntled ex-samurai in Satsuma and elsewhere.» Saigō fought for a moral revolution, not a material one, and he described his revolt as a check on the declining morality of a new, Westernizing materialism.[20]

In 2014, the movie was one of several discussed by Keli Goff in The Daily Beast in an article on white savior narratives in film,[21] a cinematic trope studied in sociology, for which The Last Samurai has been analyzed.[22] David Sirota at Salon saw the film as «yet another film presenting the white Union army official as personally embodying the North’s Civil War effort to liberate people of color» and criticizing the release poster as «a not-so-subtle message encouraging audiences to (wrongly) perceive the white guy — and not a Japanese person — as the last great leader of the ancient Japanese culture.»[23]

In a 2022 interview with The Guardian, Ken Watanabe stated that he didn’t think of The Last Samurai as a white savior narrative and that it was a turning point for Asian representation in Hollywood. Watanabe also stated, “Before The Last Samurai, there was this stereotype of Asian people with glasses, bucked teeth and a camera,” […] It was stupid, but after The Last Samurai came out, Hollywood tried to be more authentic when it came to Asian stories.” [24]

See also[edit]

- Foreign government advisors in Meiji Japan

- Ōmura Masujirō

- French Military Mission to Japan (1867)

- Mark Rappaport (creature effects artist)

References[edit]

- ^ «The Last Samurai». British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b «The Last Samurai». Lumiere. European Audiovisual Observatory. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ a b c «The Last Samurai (2003)». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ «The Last Samurai Filming Locations | New Zealand». www.newzealand.com. Retrieved 2022-08-11.

- ^ The Last Samurai: Original Motion Picture Score (CD liner notes). Hans Zimmer. Warner Sunset Records. 2003.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b «The Last Samurai – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack». Allmusic.com. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ «The Last Samurai (2003) – News» Archived 2009-02-10 at the Wayback Machine. CountingDown.com. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ «Sampling Japanese comment» Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine. Asia Arts. UCLA.edu. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Rich, Motoko (January 4, 2004). «Land Of the Rising Cliché». The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ «The Last Samurai«. Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ «The Last Samurai«. Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 5, 2003). «The Last Samurai» Archived 2012-10-09 at the Wayback Machine. Chicago Sun-Times. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ History Buffs: The Last Samurai

- ^ «The Last Samurai (2003) — Box Office Mojo». www.boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ^ «Aiming to get its name in lights, Japan pitches movie locations». Nikkei Asian Review. January 23, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Schwarzacher, Lukas (1 February 2005). «Japan’s B.O. tops record». Variety. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ «The 76th Academy Awards (2004) Nominees and Winners». Oscars.org. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (November 30, 2003). «The Last Samurai» Archived 2012-11-12 at the Wayback Machine. Variety. Reed Elsevier Inc. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Schultz, Cathy. «The Last Samurai offers a Japanese History Lesson». History in the Movies. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Ivan Morris (1975), The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of japanese, chapter 9, Saigō Takamori. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0030108112.

- ^ Goff, Keli (May 4, 2014). «Can ‘Belle’ End Hollywood’s Obsession with the White Savior?». The Daily Beast. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ Hughey, Matthew (2014). The White Savior Film: Content, Critics, and Consumption. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-1001-6.

- ^ «Oscar loves a white savior». Salon. February 22, 2013.

- ^ Lee, Ann (19 May 2022). «‘Each little thing in my life is precious’: Ken Watanabe on cancer, childhood and Hollywood cliches». The Guardian. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

Further reading[edit]

- Primadhy Wicaksono (2007). «THE INFLUENCE OF BUSHIDO ON NATHAN ALGREN’S PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN JOHN LOGAN’S MOVIE SCRIPT THE LAST SAMURAI» (PDF). Yogyakarta: Sanata Dharma University. — Bachelor of Education (Indonesian: Sarjana Pendidikan) thesis — Written in English with an abstract in Indonesian

External links[edit]

- Official website

- The Last Samurai at IMDb

- The Last Samurai at AllMovie

- The Last Samurai at the TCM Movie Database

- The Last Samurai at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Last Samurai at Box Office Mojo

- Does The Last Samurai have the saddest movie death? at AMCTV.com

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Last Samurai | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Edward Zwick |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | John Logan |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John Toll |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Hans Zimmer |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

154 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $140 million[3] |

| Box office | $456.8 million[3] |

The Last Samurai is a 2003 epic period action drama film directed and co-produced by Edward Zwick, who also co-wrote the screenplay with John Logan and Marshall Herskovitz from a story devised by Logan. The film stars Ken Watanabe in the title role, with Tom Cruise, who also co-produced, as a soldier-turned-samurai who befriends him, and Timothy Spall, Billy Connolly, Tony Goldwyn, Hiroyuki Sanada, Koyuki, and Shin Koyamada in supporting roles.

Tom Cruise portrays an American captain of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, whose personal and emotional conflicts bring him into contact with samurai warriors in the wake of the Meiji Restoration in 19th century Japan. The film’s plot was inspired by the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion led by Saigō Takamori, and the Westernization of Japan by foreign powers, though in the film the United States is portrayed as the primary force behind the push for Westernization. It is also influenced by the stories of Jules Brunet, a French Imperial Guard sub-lieutenant who fought alongside Enomoto Takeaki in the earlier Boshin War; Philip Kearny, a United States Army (Union Army) major general and French Imperial Guard soldier, notable for his leadership in the American Civil War, who fought against the Tututni tribe in the Rogue River Wars in Oregon; and, to a lesser extent, by Frederick Townsend Ward, an American mercenary who helped Westernize the Chinese army by forming the Ever Victorious Army.

The Last Samurai grossed a total of $456 million[3] at the box office and received positive reviews, with praise for the acting, visuals and Zimmer’s score but criticism for some of its portrayals. It was nominated for several awards, including four Academy Awards, three Golden Globe Awards, and two National Board of Review Awards.

Plot[edit]

In 1876, former U.S. Army Captain Nathan Algren, a skilled soldier who has become a bitter alcoholic traumatized by the atrocities he committed during the American Indian Wars, is approached by his former commanding officer Colonel Bagley. Bagley asks him to train the newly created Imperial Japanese Army for a Japanese businessman, Omura, who intends to use the army to suppress a Samurai-headed rebellion against Japan’s new emperor. Despite his hatred of Bagley, the impoverished Algren takes the job for the money. He is accompanied to Japan by his old friend, Sergeant Zebulon Gant. Upon arriving, Algren meets Simon Graham, a British translator knowledgeable about the samurai.

Algren learns that the Imperial soldiers are simply conscripted peasants with shoddy training and little discipline. While training them to shoot, Algren is informed that the samurai are attacking one of Omura’s railroads; Omura sends the army there, despite Algren’s protests that they are not ready. The battle is a disaster, as the undisciplined conscripts are routed, and Gant is killed. Algren fights to the last before he is surrounded; expecting to die, he is taken prisoner when samurai leader Katsumoto decides to spare him. Algren is taken to Katsumoto’s village. While he is poorly treated at first, he eventually gains the samurai’s respect and grows close to Katsumoto. Algren overcomes his alcoholism and guilt, learns the Japanese language and culture, and is trained in the art of kenjutsu. He develops sympathy for the samurai, who are upset that the pace of modern technology has eroded the traditions of their society. Algren and Taka, Katsumoto’s sister and the widow of a samurai killed by Algren, develop an unspoken affection for each other.

One night, a group of ninja infiltrate the village and attempt to assassinate Katsumoto. Algren saves Katsumoto’s life, and then helps defend the village, concluding that Omura must have hired the ninjas. Katsumoto requests a meeting with Emperor Meiji in Tokyo. He brings Algren, intending to release him. Upon arriving in Tokyo, Algren sees that the Imperial Army has become a well-trained and fully equipped force led by Bagley. Katsumoto, to his dismay, discovers that the young and inexperienced Emperor has become a puppet of Omura. At a government meeting, Omura orders Katsumoto’s arrest for carrying a sword in public and tells him to perform seppuku the next day to redeem his honor. Meanwhile, Algren refuses Bagley’s offer to resume command of the army, prompting Omura to send assassins after him, but Algren kills the assailants and then assists the samurai in freeing Katsumoto. During the rescue, Katsumoto’s son Nobutada is mortally wounded, his sacrifice allowing the others to escape.

As the Imperial Army marches to crush the rebellion, a grieving Katsumoto contemplates seppuku. Algren convinces him to fight and joins the samurai in battle. The samurai use the Imperial Army’s overconfidence to lure them into a trap; the ensuing battle inflicts massive casualties on both sides and forces the Imperial soldiers to retreat. Knowing that Imperial reinforcements are coming, and defeat is inevitable, Katsumoto orders a suicidal cavalry charge on horseback. The samurai withstand an artillery barrage and break through Bagley’s line. Algren kills Bagley, but the samurai are quickly mowed down by Gatling guns. The Imperial captain, previously trained by Algren and horrified by the sight of the dying samurai, orders the soldiers to cease fire, outraging Omura. Katsumoto, mortally wounded, commits seppuku with Algren’s help as the soldiers at the scene kneel in respect.

Later, as trade negotiations conclude, the injured Algren interrupts the proceedings. He presents the Emperor with Katsumoto’s sword and asks him to remember the traditions for which Katsumoto and his fellow Samurai fought and died. The Emperor realizes that while Japan should modernize, it cannot forget its own culture and history. He rejects the trade offer, and when Omura protests, the Emperor threatens to seize Omura’s assets and distribute them among the populace. Omura claims to be disgraced, and the Emperor offers him Katsumoto’s sword, saying that if the shame is too great, Omura should commit seppuku. Omura relents and leaves.

While various rumours regarding Algren’s fate circulate, Graham concludes that Algren had returned to the village to reunite with Taka.

Cast[edit]

- Tom Cruise as Captain Nathan Algren, a Civil War and Indian War veteran haunted by his role in the massacre of Native Americans at the Washita River. Following his discharge from the United States Army, he agrees to help the new Meiji Restoration government train its first Western-style conscript army for a significant sum of money. During the army’s first battle he is captured by the samurai Katsumoto and taken to the village of Katsumoto’s son, where he soon becomes intrigued with the way of the samurai and decides to join them in their cause. His journal entries reveal his impressions about traditional Japanese culture, which almost immediately evolve into unrestrained admiration.

- Ken Watanabe as Lord Moritsugu Katsumoto, the eponymous «Last Samurai,» a former daimyo who was once Emperor Meiji’s most trusted teacher. His displeasure with the influence of Omura and other Western reformers on the Emperor lead him to organize his fellow samurai in a revolt, which he hopes will convince the government not to destroy the samurai’s place in Japanese society. Katsumoto is based on real-life samurai Saigō Takamori, who led the Satsuma Rebellion.

- Koyuki Kato as Taka, widow of a samurai slain by Nathan Algren and younger sister of Lord Katsumoto. She and Algren develop feelings for each other, and she gives him her husband’s armor to wear in the final battle of the rebellion.

- Shin Koyamada as Nobutada Katsumoto, Katsumoto’s son who is responsible for the village where Algren is sent. Nobutada befriends Algren when Katsumoto assigns him to teach Algren Japanese culture and the Japanese language. He dies when he willingly chooses to distract Imperial troops so his father can escape their custody.

- Tony Goldwyn as Colonel Bagley, Nathan Algren’s former commanding officer in the 7th Cavalry Regiment, who hires him to serve as a training instructor for the Imperial Army despite Algren’s hatred of Bagley for his role in the Washita River massacre. In contrast to Algren, Bagley is arrogant and dismissive of the samurai, at one point referring to them nothing more than «savages with bows and arrows». He is killed by Algren who throws a sword into his chest when Bagley tries to shoot Katsumoto in the final battle.

- Masato Harada as Matsue Omura, an industrialist and pro-reform politician. He quickly imports Westernization and modernization while making money for himself through his ownership of Japan’s railroads. Coming from a merchant family, a social class repressed during the days of Shogun rule, Omura openly expresses his contempt for the samurai and takes advantage of Emperor Meiji’s youth to become his chief advisor, persuading him to form a Western-style army for the sole purpose of wiping out Katsumoto and his rebels while ignoring their grievances. His appearance is designed to evoke the image of Okubo Toshimichi, a leading reformer during the Meiji Restoration. Harada noted that he was deeply interested in joining the film after witnessing the construction of Emperor Meiji’s conference room on sound stage 19 (where Humphrey Bogart had once acted) at Warner Brothers studios.[citation needed]

- Shichinosuke Nakamura as Emperor Meiji. Credited with the implementation of the Meiji reforms to Japanese society, the Emperor is eager to import Western ideas and practices to modernize and empower Japan to become a strong nation. However, his inexperience causes him to rely heavily on the advice of men like Omura, who have their own agendas. His appearance bears a strong resemblance to Emperor Meiji during the 1860s (when his authority as Emperor was not yet firmly established) rather than during the 1870s, when the film takes place.

- Hiroyuki Sanada as Ujio, a master swordsman and one of Katsumoto’s most trusted followers. He teaches Algren the art of sword fighting, coming to respect him as an equal. He is one of the last samurai to die in the final battle, being gunned down during Katsumoto’s charge.

- Timothy Spall as Simon Graham, a British photographer and scholar hired as an interpreter for Captain Algren and his non-English speaking soldiers. Initially portrayed as a friendly yet mission-oriented and practical-minded companion, he later comes to sympathize with the samurai cause and helps Algren rescue Katsumoto from Imperial soldiers.

- Seizo Fukumoto as Silent Samurai, an elderly samurai tasked with monitoring Algren during his time in the village, who calls the samurai «Bob». «Bob» ultimately saves Algren’s life (and speaking for the first and only time, «Algren-san!») by taking a bullet meant for him in the final battle.

- Billy Connolly as Sergeant Zebulon Gant, an Irish American Civil War veteran who served with and is loyal to Algren, persuading him to come to Japan and working with him to train the Imperial Army. During the first battle, he is killed by Hirotaro (Taka’s husband) after being wounded with a spear.

- Shun Sugata as Nakao, a tall samurai who wields a naginata and is skilled in jujutsu. He assists Algren in rescuing Katsumoto and dies along with the other samurai in the final battle.

Production[edit]

Filming took place in New Zealand, mostly in the Taranaki region,[4] with mostly Japanese cast members and an American production crew. This location was chosen due to the fact that Egmont/Mount Taranaki resembles Mount Fuji, and also because there is a lot of forest and farmland in the Taranaki region. American Location Manager Charlie Harrington saw the mountain in a travel book and encouraged the producers to send him to Taranaki to scout the locations. This acted as a backdrop for many scenes, as opposed to the built up cities of Japan. Several of the village scenes were shot on the Warner Bros. Studios backlot in Burbank, California. Some scenes were shot in Kyoto and Himeji, Japan. There were 13 filming locations altogether. Tom Cruise did his own stunts for the film.

The film is based on an original screenplay entitled «The Last Samurai», from a story by John Logan. The project itself was inspired by writer and director Vincent Ward. Ward became executive producer on the film – working in development on it for nearly four years and after approaching several directors (Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Weir), until he became interested with Edward Zwick. The film production went ahead with Zwick and was shot in Ward’s native New Zealand.

The film was based on the stories of Jules Brunet, a French Imperial Guard sub-lieutenant who fought alongside Enomoto Takeaki in the earlier Boshin War; Philip Kearny, a United States Army (Union Army) and French Imperial Guard soldier, notable for his leadership in the American Civil War, who fought against the Tututni tribe in the Rogue River Wars in Oregon; and Frederick Townsend Ward, an American mercenary who helped Westernize the Qing army by forming the Ever Victorious Army. The historical roles of other European nations who were involved in the westernization of Japan are largely attributed to the United States in the film, although the film references European involvement as well.

Music[edit]

| The Last Samurai: Original Motion Picture Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Film score by

Hans Zimmer |

|||

| Released | November 25, 2003 | ||

| Genre | Soundtrack | ||

| Length | 59:41 | ||

| Label | Warner Sunset | ||

| Producer | Hans Zimmer | ||

| Hans Zimmer chronology | |||

|

The Last Samurai: Original Motion Picture Score was released on November 25, 2003, by Warner Sunset Records.[5] All music on the soundtrack was composed, arranged, and produced by Hans Zimmer, performed by the Hollywood Studio Symphony, and conducted by Blake Neely.[6] It peaked at number 24 on the US Top Soundtracks chart.[6]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

The film achieved higher box office receipts in Japan than in the United States.[7] Critical reception in Japan was generally positive.[8] Tomomi Katsuta of The Mainichi Shinbun thought that the film was «a vast improvement over previous American attempts to portray Japan», noting that director Edward Zwick «had researched Japanese history, cast well-known Japanese actors and consulted dialogue coaches to make sure he didn’t confuse the casual and formal categories of Japanese speech.» Katsuta still found fault with the film’s idealistic, «storybook» portrayal of the samurai, stating: «Our image of samurai is that they were more corrupt.» As such, he said, the noble samurai leader Katsumoto «set my teeth on edge.»[9]

In the United States, review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 66% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 223 reviews, with an average score of 6.40/10. The site’s consensus states: «With high production values and thrilling battle scenes, The Last Samurai is a satisfying epic.»[10] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted mean rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film received an average score of 55, based on reviews from 43 critics, indicating «mixed or average reviews».[11]

Roger Ebert of Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three and a half stars out of four, saying «beautifully designed, intelligently written, acted with conviction, it’s an uncommonly thoughtful epic.»[12]

One online analyst compares the movie favorably to Dances with Wolves in that each protagonist meets and combats a «technologically backward people». Both Costner’s and Cruise’s characters have suffered through a series of traumatic and brutal battles. Each ultimately uses his experiences to later assist his new friends. Each comes to respect his newly adopted culture. Each even fights with his new community against the people and traditions from which he came.[13]

Box office[edit]

As of January 1, 2016, the film had grossed $456.8 million against a production budget of $140 million. It grossed $111,127,263 in the United States and Canada, and $345,631,718 in other countries.[14] It was one of the most successful box office hits in Japan,[15] where it grossed ¥13.7 billion ($132 million).,[16]

Accolades[edit]

| Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[17] | Best Supporting Actor | Ken Watanabe | Nominated |

| Best Art Direction | Lilly Kilvert and Gretchen Rau | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Ngila Dickson | Nominated | |

| Best Sound Mixing | Andy Nelson, Anna Behlmer and Jeff Wexler | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama | Tom Cruise | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ken Watanabe | Nominated | |

| Best Score | Hans Zimmer | Nominated | |

| National Board of Review | Top Ten Films | 2nd place | |

| Best Director | Edward Zwick | Won | |

| Satellite Awards | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Actor | Tom Cruise | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ken Watanabe | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Hans Zimmer | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | John Toll | Won | |

| Best Art Direction and Production Design | Lilly Kilvert and Gretchen Rau | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Ngila Dickson | Won | |

| Best Editing | Victor Du Bois and Steven Rosenblum | Won | |

| Best Sound | Andy Nelson, Anna Behlmer and Jeff Wexler | Nominated | |

| Best Visual Effects | Nominated | ||

| Visual Effects Society Awards | Outstanding Supporting Visual Effects | Jeffrey A. Okun, Thomas Boland, Bill Mesa, Ray McIntyre Jr. | Won |

| Japan Academy Film Prize | Outstanding Foreign Language Film | Won | |

| Taurus World Stunt Awards | Best Fire Stunt | Won |

Criticism and debate[edit]

The Seikanron debate of 1873. Saigō Takamori insisted that Japan should go to war with Korea.

Motoko Rich of The New York Times observed that the film has opened up a debate, «particularly among Asian-Americans and Japanese,» about whether the film and others like it were «racist, naïve, well-intentioned, accurate – or all of the above.»[9]

Todd McCarthy, a film critic for the Variety magazine, wrote: «Clearly enamored of the culture it examines while resolutely remaining an outsider’s romanticization of it, yarn is disappointingly content to recycle familiar attitudes about the nobility of ancient cultures, Western despoilment of them, liberal historical guilt, the unrestrainable greed of capitalists and the irreducible primacy of Hollywood movie stars.»[18]

According to the history professor Cathy Schultz, «Many samurai fought Meiji modernization not for altruistic reasons but because it challenged their status as the privileged warrior caste. Meiji reformers proposed the radical idea that all men essentially being equal…. The film also misses the historical reality that many Meiji policy advisors were former samurai, who had voluntarily given up their traditional privileges to follow a course they believed would strengthen Japan.»[19]

The fictional character of Katsumoto bears a striking resemblance to the historical figure of Saigō Takamori, a hero of the Meiji Restoration and the leader of the ineffective Satsuma Rebellion, who appears in the histories and legends of modern Japan as a hero against the corruption, extravagance, and unprincipled politics of his contemporaries. «Though he had agreed to become a member of the new government,» wrote the translator and historian Ivan Morris, «it was clear from his writings and statements that he believed the ideals of the civil war were being vitiated. He was opposed to the excessively rapid changes in Japanese society and was particularly disturbed by the shabby treatment of the warrior class.» Suspicious of the new bureaucracy, he wanted power to remain in the hands of the samurai class and the Emperor, and for those reasons, he had joined the central government. «Edicts like the interdiction against carrying swords and wearing the traditional topknot seemed like a series of gratuitous provocations; and, though Saigō realized that Japan needed an effective standing army to resist pressure from the West, he could not countenance the social implications of the military reforms. For this reason Saigō, although participating in the Okinoerabu government, continued to exercise a powerful appeal among disgruntled ex-samurai in Satsuma and elsewhere.» Saigō fought for a moral revolution, not a material one, and he described his revolt as a check on the declining morality of a new, Westernizing materialism.[20]

In 2014, the movie was one of several discussed by Keli Goff in The Daily Beast in an article on white savior narratives in film,[21] a cinematic trope studied in sociology, for which The Last Samurai has been analyzed.[22] David Sirota at Salon saw the film as «yet another film presenting the white Union army official as personally embodying the North’s Civil War effort to liberate people of color» and criticizing the release poster as «a not-so-subtle message encouraging audiences to (wrongly) perceive the white guy — and not a Japanese person — as the last great leader of the ancient Japanese culture.»[23]

In a 2022 interview with The Guardian, Ken Watanabe stated that he didn’t think of The Last Samurai as a white savior narrative and that it was a turning point for Asian representation in Hollywood. Watanabe also stated, “Before The Last Samurai, there was this stereotype of Asian people with glasses, bucked teeth and a camera,” […] It was stupid, but after The Last Samurai came out, Hollywood tried to be more authentic when it came to Asian stories.” [24]

See also[edit]

- Foreign government advisors in Meiji Japan

- Ōmura Masujirō

- French Military Mission to Japan (1867)

- Mark Rappaport (creature effects artist)

References[edit]

- ^ «The Last Samurai». British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b «The Last Samurai». Lumiere. European Audiovisual Observatory. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ a b c «The Last Samurai (2003)». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ «The Last Samurai Filming Locations | New Zealand». www.newzealand.com. Retrieved 2022-08-11.

- ^ The Last Samurai: Original Motion Picture Score (CD liner notes). Hans Zimmer. Warner Sunset Records. 2003.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b «The Last Samurai – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack». Allmusic.com. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ «The Last Samurai (2003) – News» Archived 2009-02-10 at the Wayback Machine. CountingDown.com. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ «Sampling Japanese comment» Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine. Asia Arts. UCLA.edu. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Rich, Motoko (January 4, 2004). «Land Of the Rising Cliché». The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ «The Last Samurai«. Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ «The Last Samurai«. Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 5, 2003). «The Last Samurai» Archived 2012-10-09 at the Wayback Machine. Chicago Sun-Times. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ History Buffs: The Last Samurai

- ^ «The Last Samurai (2003) — Box Office Mojo». www.boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ^ «Aiming to get its name in lights, Japan pitches movie locations». Nikkei Asian Review. January 23, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Schwarzacher, Lukas (1 February 2005). «Japan’s B.O. tops record». Variety. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ «The 76th Academy Awards (2004) Nominees and Winners». Oscars.org. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (November 30, 2003). «The Last Samurai» Archived 2012-11-12 at the Wayback Machine. Variety. Reed Elsevier Inc. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Schultz, Cathy. «The Last Samurai offers a Japanese History Lesson». History in the Movies. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Ivan Morris (1975), The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of japanese, chapter 9, Saigō Takamori. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0030108112.

- ^ Goff, Keli (May 4, 2014). «Can ‘Belle’ End Hollywood’s Obsession with the White Savior?». The Daily Beast. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ Hughey, Matthew (2014). The White Savior Film: Content, Critics, and Consumption. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-1001-6.

- ^ «Oscar loves a white savior». Salon. February 22, 2013.