This article is about the Islamic holy day. For the traditional dessert, see Ashure. For other uses, see Ashura (disambiguation).

| Ashura عَاشُورَاء |

|

|---|---|

Procession for Ashura at Imam Hossein Square in Tehran, Iran (2016) |

|

| Type | Islamic (Shia and Sunni) |

| Significance | In Shia Islam: Mourning the death of Husayn ibn Ali during the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE In Sunni Islam: Celebrating the salvation of Moses and the Israelites from their enslavement in Biblical Egypt |

| Observances |

|

| Date | 10 Muharram |

| 2022 date | 8 August[1] |

| Frequency | Annual (Islamic calendar) |

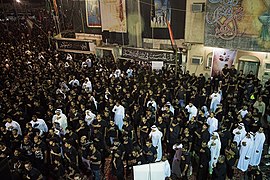

Ashura (Arabic: عَاشُورَاء, ʿĀshūrāʾ, [ʕaːʃuːˈraːʔ]) is a day of commemoration in Islam. It occurs annually on the 10th of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar. Among Shia Muslims, Ashura is observed through large demonstrations of high-scale mourning as it marks the death of Husayn ibn Ali (a grandson of Muhammad), who was beheaded during the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE.[4] Among Sunni Muslims, Ashura is observed through celebratory fasting as it marks the day of salvation for Moses and the Israelites, who successfully escaped from Biblical Egypt (where they were enslaved and persecuted) after Moses called upon God’s power to part the Red Sea.[5] While Husayn’s death is also regarded as a great tragedy by Sunnis, open displays of mourning are either discouraged or outright prohibited, depending on the specific act.[6]

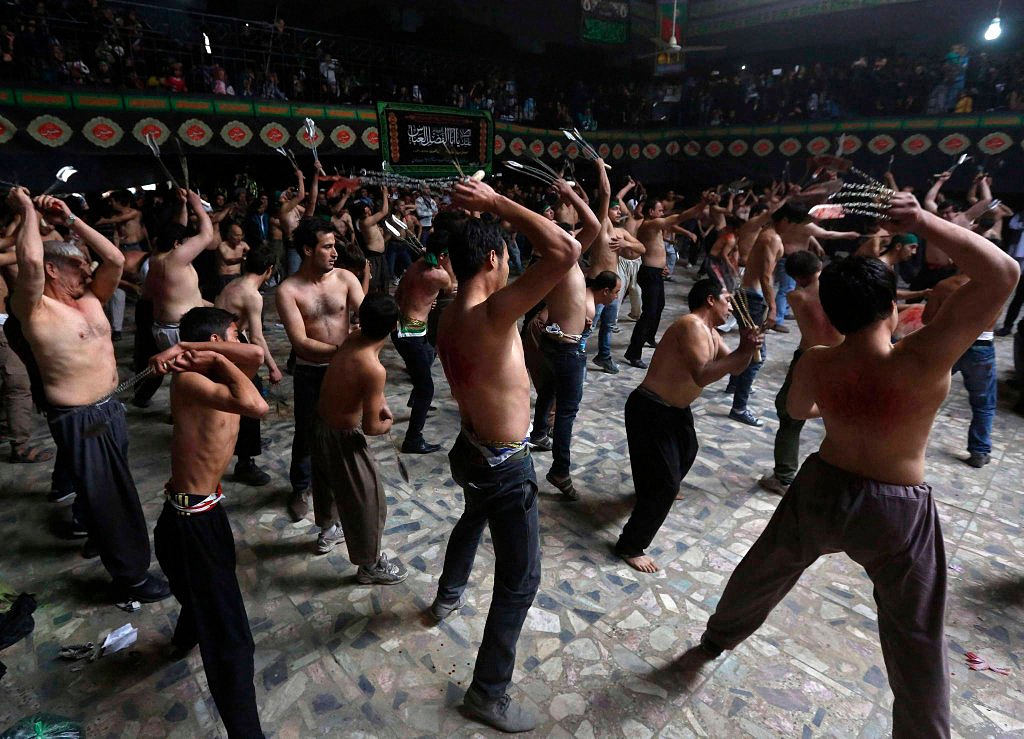

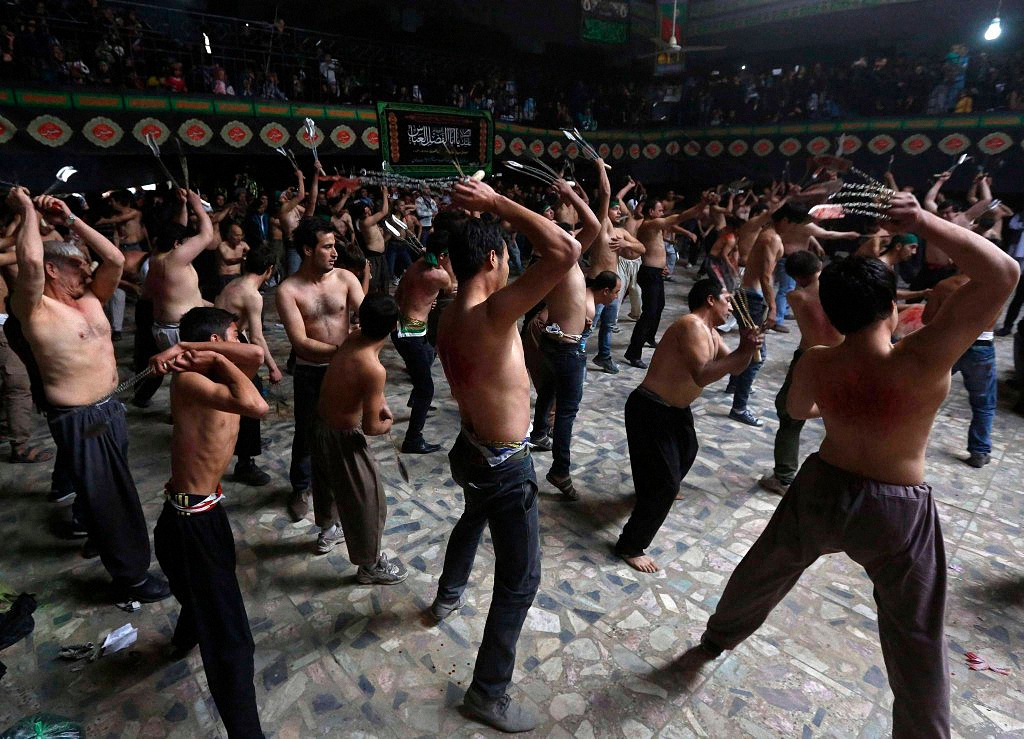

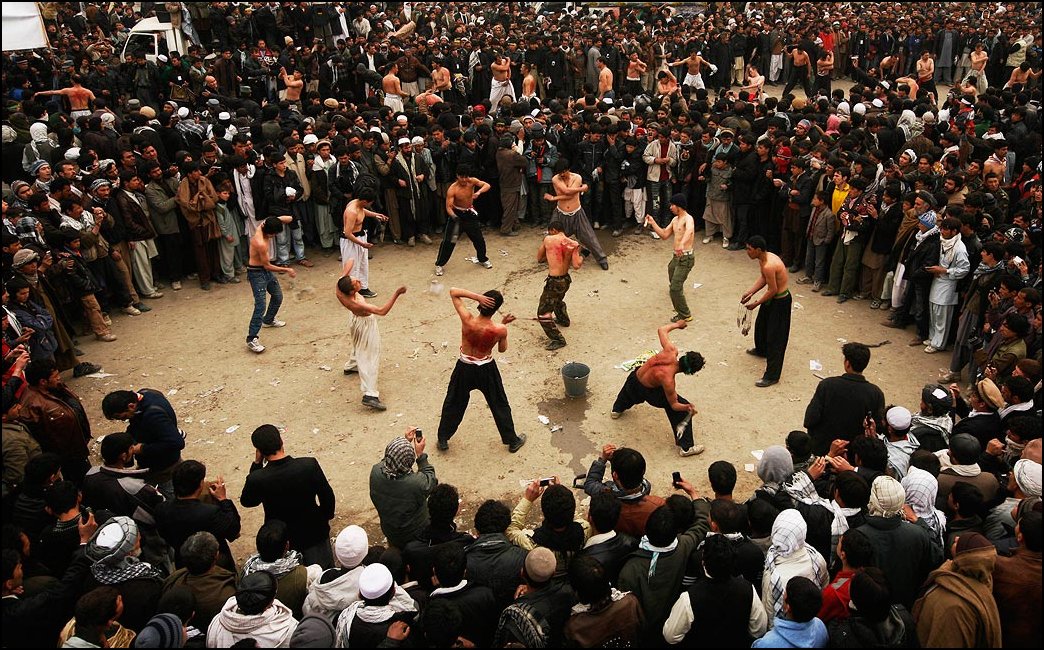

In Shia communities, Ashura observances are typically carried out in group processions and are accompanied by a variety of rituals ranging from weeping and shrine pilgrimages to the more controversial acts of self-flagellation and chest-beating.[7] In Sunni communities, there are three rounds of fasting, based on Muhammad’s hadith: on the day before Ashura, on the day of Ashura, and on the day after Ashura; while fasting for Ashura is not obligatory, it is strongly encouraged.[8][9] In folk traditions across countries such as Morocco and Algeria, the day of Ashura is variously celebrated with special foods, bonfires, or carnivals, though these practices are not supported by religious authorities.[10] Due to the drastically differing methods of observance between Sunnis and Shias, the day of Ashura has come to acquire a political dimension in some Islamic countries, and particularly in Iran, where Shia Islam is the official state religion. Additionally, it has also served as a trigger for controversy as well as violent incidents between the two communities in countries such as Iraq and Pakistan.

Etymology[edit]

The root of the word Ashura means tenth in Semitic languages; hence the name, literally translated, means «the tenth day». According to the Islamicist A. J. Wensinck, the name is derived from the Hebrew ʿāsōr, with the Aramaic determinative ending.[11]

Origin[edit]

Sunni Islam[edit]

Fasting on Ashura, the tenth day of the Islamic month of Muharram was a practice established by Muhammad in the early days of Islam that commemorates the parting of the Red Sea by Moses.[12][13] Its beginning is recounted in a sahih hadith recorded through Ibn Abbas by al-Bukhari:

When the Prophet (ﷺ) came to Medina, he found (the Jews) fasting on the day of ‘Ashura’ (i.e. 10th of Muharram). They used to say: «This is a great day on which Allah saved Moses and drowned the folk of Pharaoh. Moses observed the fast on this day, as a sign of gratitude to Allah.» The Prophet (ﷺ) said, «I am closer to Moses than they.» So, he observed the fast (on that day) and ordered the Muslims to fast on it.[14]

This has been analysed as reflecting an encounter between Muhammad and some Jews fasting for Yom Kippur, on the tenth day of Tishri, in commemoration of Moses, upon which he began to fast on that day and instruct fellow Muslims to fast.[15][16] The practice would thus have been established at a time when the Islamic and Jewish calendars were synced.[17] However, Muhammad later received a revelation to adjust the Islamic calendar, in the verse of Nasi’, and with this Ramadan, the ninth month, became the month of fasting, and the obligation to fast on Ashura was dropped, as Ashura became distinct from its Jewish predecessor of Yōm Kippur.[12][17] According to a sahih hadith narrated through Aisha:

During the Pre-lslamic Period of ignorance the Quraish used to observe fasting on the day of ‘Ashura’, and the Prophet (ﷺ) himself used to observe fasting on it too. But when he came to Medina, he fasted on that day and ordered the Muslims to fast on it. When (the order of compulsory fasting in) Ramadan was revealed, fasting in Ramadan became an obligation, and fasting on ‘Ashura’ was given up, and who ever wished to fast (on it) did so, and whoever did not wish to fast on it, did not fast.[18]

It is still widely considered desirable (mustahab) to fast on Ashura (10th day), and also on Tasua (9th day).[19] With hadith in Jami At-Tirmidhi signifying that God forgives the sins of the year prior for people fasting Ashura.[20]

Shia Islam[edit]

Martyrdom of Ḥusayn[edit]

Millions of Shia Muslims gather around the Husayn Mosque in Karbala after making the pilgrimage on foot during Arba’een, which is a Shia religious observation that occurs 40 days after the Day of Ashura.

The Battle of Karbala took place during the period of decay resulting from the succession of Yazid I.[21][22] Immediately after his succession, Yazid instructed the governor of Medina to compel Ḥusayn and a few other prominent figures to pledge their allegiance (Bay’ah).[23] However, Ḥusayn refused to do this, believing that Yazid was going against the teachings of Islam and changing the sunnah of Muhammad.[citation needed] So, accompanied by his household, his sons, brothers, and the sons of Hasan, he left Medina to seek asylum in Mecca.[23]

In Mecca, Ḥusayn learned that Yazid had sent assassins to kill him during the Hajj. To preserve the sanctity of the city and of the Kaaba, Husayn abandoned his Hajj and encouraged his companions to follow him to Kufa without realising that the situation there had taken an adverse turn.[23]

On the way there, Ḥusayn found that his messenger, Muslim ibn Aqeel, had been killed in Kufa and encountered the vanguard of the army of Ubaydullah ibn Ziyad. Ḥe addressed the Kufan army, reminding them that they had invited him to come there because they were without an Imam, and told them that he intended to proceed to Kufa with their support; however, if they were now opposed to his coming, he would return to Mecca. When the army urged him to take another route, he turned to the left and reached Karbala, where the army forced him to stop at a location with little water.[23]

Governor Ubaydullah ibn Ziyad instructed Umar ibn Sa’ad, the head of the Kufan army, to again offer Ḥusayn and his supporters the opportunity to swear allegiance to Yazid. He also ordered Umar ibn Sa’ad to cut Ḥusayn and his followers off from access to the water of the Euphrates.[23] The next morning, Umar ibn Sa’ad arranged the Kufan army in battle formation.[23]

The Battle of Karbala lasted from sunrise to sunset on 10 October 680 (Muharram 10, 61 AH). Husayn’s small group of companions and family members (around 72 men plus women and children)[note 1][25][26] fought against Umar ibn Sa’ad’s army and were killed near the Euphrates, from which they were not allowed to drink. The renowned historian Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī states:

… [T]hen fire was set to their camp and the bodies were trampled by the hoofs of the horses; nobody in the history of the human kind has seen such atrocities.[27]

Once the Umayyad troops had murdered Ḥusayn and his male followers, they looted the tents, stripped the women of their jewellery, and took the skin upon which Zain al-Abidin was prostrate. Ḥusayn’s sister Zaynab was taken along with the enslaved women to the king in Damascus where she was imprisoned before being allowed to return to Medina after a year.[28][29]

Significance[edit]

The first assembly (majlis) of the Commemoration of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī is said to have been held by Zaynab in prison. In Damascus she is also reported to have delivered a poignant oration. The prison sentence ended when Husayn’s four-year-old daughter, Ruqayyah bint Husayn, who would often cry to be allowed to see her father, died in captivity, probably after seeing his mutilated head. Her death caused an uproar in the city, and, fearing an uprising, Yazid freed the captives.[30]

According to Ignác Goldziher,

Ever since the black day of Karbala, the history of this family … has been a continuous series of sufferings and persecutions. These are narrated in poetry and prose, in a richly cultivated literature of martyrologies … ‘More touching than the tears of the Shi’is’ has even become an Arabic proverb.[31]

Imam Zayn Al Abidin said the following:

It is said that for forty years whenever food was placed before him, he would weep. One day a servant said to him, ‘O son of Allah’s Messenger! Is it not time for your sorrow to come to an end?’ He replied, ‘Woe upon you! Jacob the prophet had twelve sons, and Allah made one of them disappear. His eyes turned white from constant weeping, his head turned grey out of sorrow, and his back became bent in gloom,[note 2] though his son was alive in this world. But I watched while my father, my brother, my uncle, and seventeen members of my family were slaughtered all around me. How should my sorrow come to an end?’[note 3][32][33]

Husayn’s grave became a pilgrimage site for Shia Muslims within a few years of his death. A tradition of pilgrimage to the shrine of Imam Husayn and the other Karbala martyrs, known as Ziarat ashura, quickly developed.[34] The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs tried to prevent construction of the shrines and discouraged pilgrimage.[35] The tomb and its annexes were destroyed by the Abbasid caliph Al-Mutawakkil in 850–851 and Shia pilgrimage was prohibited, but shrines in Karbala and Najaf were built by the Buwayhid emir ‘Adud al-Daula in 979–80.[36]

Public rites of remembrance for Husayn’s martyrdom developed from the early pilgrimages.[37] Under the Buyid dynasty, Mu’izz ad-Dawla officiated at a public commemoration of Ashura in Baghdad.[38] These commemorations were also encouraged in Egypt by the Fatimid caliph al-‘Aziz.[39] With the recognition of the Twelvers as the official religion by the Safavids, the Mourning of Muharram extended throughout the first ten days of Muharram.[34]

Ashura was remembered by Jafaris, Qizilbash Alevi-Turks, and Bektashis during the period of the Ottoman Empire.[41] It is of particular significance to Twelver Shias and Alawites, who consider Husayn (the grandson of Muhammad) Ahl al-Bayt, the third Imam to be the rightful successor of Muhammad.[citation needed]

According to Kamran Scot Aghaie, «The symbols and rituals of Ashura have evolved over time and have meant different things to different people. However, at the core of the symbolism of Ashura is the moral dichotomy between worldly injustice and corruption on the one hand and God-centered justice, piety, sacrifice and perseverance on the other. Also, Shiite Muslims consider the remembrance of the tragic events of Ashura to be an important way of worshipping God in a spiritual or mystical way.»[42]

Shia Muslims make pilgrimages on Ashura, as they do forty days later on ʾArbaʿīn, to the Mashhad al-Husayn, the shrine in Karbala, Iraq, that is traditionally held to be Husayn’s tomb. This is a day of remembrance, and mourning attire is worn. This is a time for sorrow and for showing respect for the person’s passing, and it is also a time for self-reflection when a believer commits themself completely to the mourning of Husayn. Shia Muslims refrain from listening to or playing music since Arabic culture generally considers playing music during death rituals to be impolite. Nor do they plan weddings or parties on this date. Instead they mourn by crying and listening to recollections of the tragedy and sermons on how Husayn and his family were martyred. This is intended to connect them with Husayn’s suffering and martyrdom, and the sacrifices he made to keep Islam alive. Husayn’s martyrdom is widely interpreted by Shia Muslims as a symbol of the struggle against injustice, tyranny, and oppression.[43] Shia Muslims believe the Battle of Karbala was between the forces of good and evil, with Husayn representing good and Yazid representing evil.[44]

Shia imams insist that Ashura should not be celebrated as a day of joy and festivity. According to the Eighth Shia Imam Ali al-Rida, it must be observed as a day of rest, sorrow, and total disregard of worldly matters.[45]

Some of the events associated with Ashura are held in special congregation halls known as «Imambargah» and Hussainia.[46]

The World Sunni Movement celebrates this day as the National Martyrs’ Day of the Muslim nation under the direction of Syed Imam Hayat.[47]

Remembrance[edit]

Azadari (mourning) rituals[edit]

The words Azadari (Persian: عزاداری), which means mourning and lamentation, and Majalis-e Aza are used exclusively in connection with the remembrance ceremonies for the martyrdom of Imam Hussain. Majalis-e Aza, also known as Aza-e Husayn, includes mourning congregations, lamentations, matam and all acts which express the grief and, above all, repulsion against what Yazid stood for.[48]

Ritual scourge for use in the Ashura procession. Syria, before 1974

These customs show solidarity with Husayn and his family. Through them, people mourn Husayn’s death and express regret for the fact that they were not present at the battle to save Husayn and his family.[49][50]

Tuwairij run[edit]

The Tuwairij run is the name of an Ashura ceremony in which millions of people from around Tuwairij in 22 km run and mourning on side of the Imam Husayn Shrine.[51] this ceremony is considered as the biggest observance of religious activities in the world.[52][53] Its importance has grown since Moḥammad Mahdī Baḥr al-ʿUlūm was quoted as saying that Hujjat bin Hasan was present at this ceremony.[54]

History[edit]

The Tuwairij was first run on Ashura 1855 when people who were at the house of Seyyed Saleh Qazvini after the mourning ceremony and the recitation of the murder of Husain bin ‘Ali cried so much from grief and sorrow that they asked Seyyed Saleh to run to the imam’s shrine to offer his condolences. Seyyed Saleh accepted their request and went to the shrine with all the mourners.[55][56][57][58]

Prohibition of the march[edit]

The march was banned by Saddam Hussein’s Ba‘athist regime between 1991 and 2003.[59][60] However, despite the ban, Tuwairij still continued and the regime executed many participants.[citation needed] The event was permitted again after 2003, and participation from outside Iraq has steadily increased.[61]

Popular customs[edit]

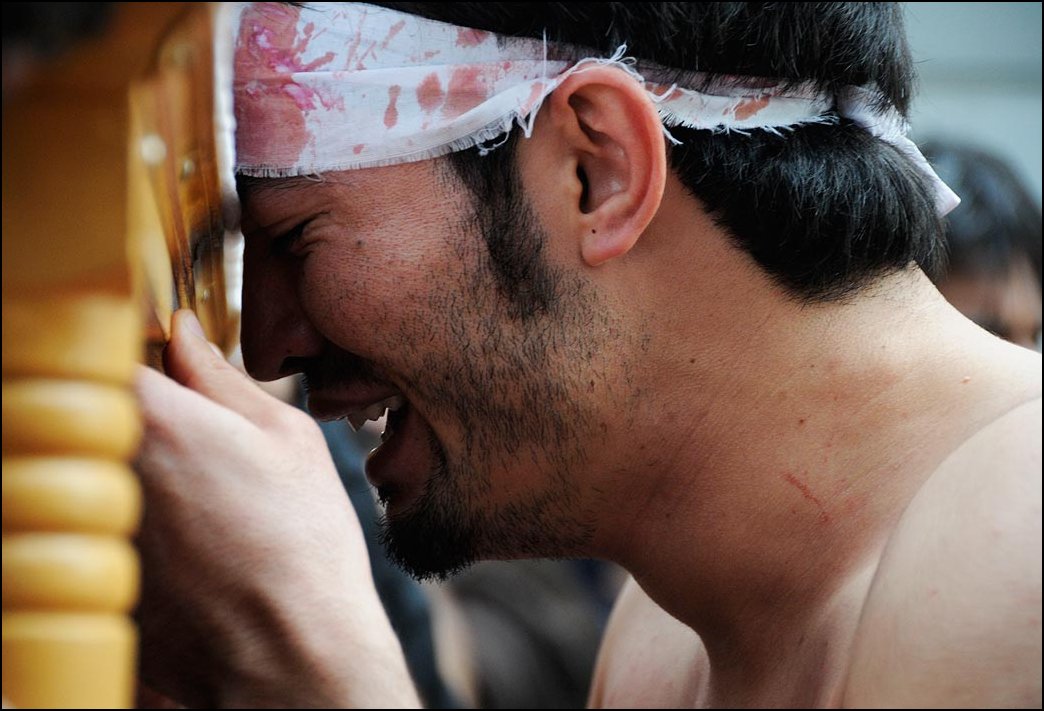

After almost 12 centuries, five main types of rituals were developed around the story of the battle of Karbala. These rituals include memorial services (majalis al-ta’ziya); visits to Husayn’s tomb in Karbala particularly on Ashura and on the fortieth day after the battle (Ziyarat Ashura and Ziyarat al-Arba’in); public mourning processions (al-mawakib al-husayniyya); representation of the battle as a play (the shabih); and personal flagellation (tatbir).[62] Some Shia Muslims believe that taking part in Ashura washes away their sins.[63] A popular Shia saying has it that «a single tear shed for Husayn washes away a hundred sins».[64]

For Shia Muslims, the commemoration of Ashura is an event of intense grief and mourning. Mourners congregate at a mosque for sorrowful, poetic recitations such as marsiya, noha, latmiya, and soaz performed in memory of the martyrdom of Husayn, lamenting and grieving to the tune of beating drums and chants of «Ya Hussain». Ulamas also give sermons on the themes of Husayn’s personality and position in Islam, and the history of his uprising. The Sheikh of the mosque retells the story of the Battle of Karbala to allow his listeners to relive the pain and sorrow endured by Husayn and his family and they read Maqtal Al-Husayn.[62][65] In some places, such as Iran, Iraq, and the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, passion plays known as Ta’zieh[66] are performed, reenacting the Battle of Karbala and the suffering and martyrdom of Husayn at the hands of Yazid.

In the Caribbean islands of Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica, Ashura, known locally as ‘Hussay’ or Hosay, may commemorate the grandson of Muhammad, but the celebration has taken on influences from other religions including Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, and the Baptist movement, so that it has become a mixture of different cultures and religion. The event is attended by both Muslims and non-Muslims in an environment of mutual respect and tolerance.[67][68] For the duration of the memorial events, it is customary for mosques and individuals to provide free meals (Nazri or Votive Food) for everyone on certain nights.[69]

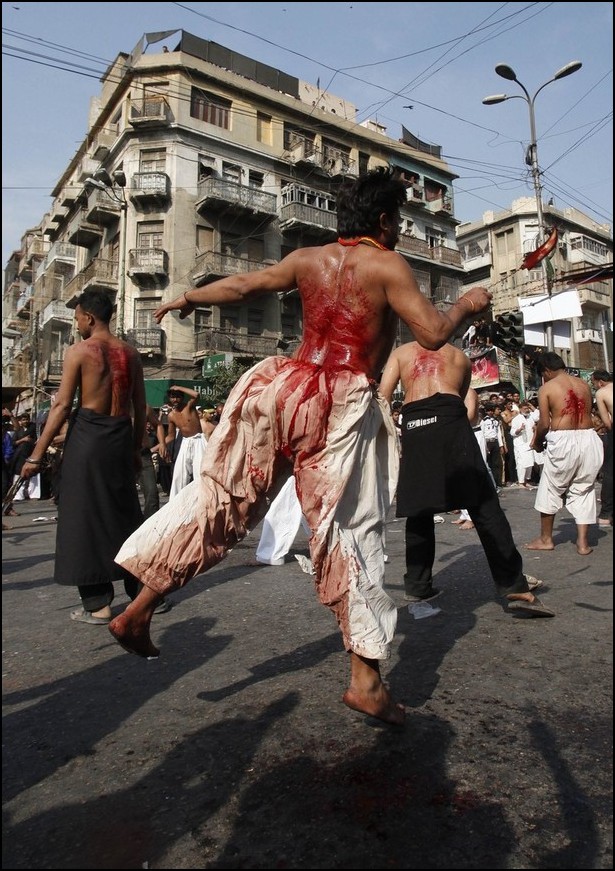

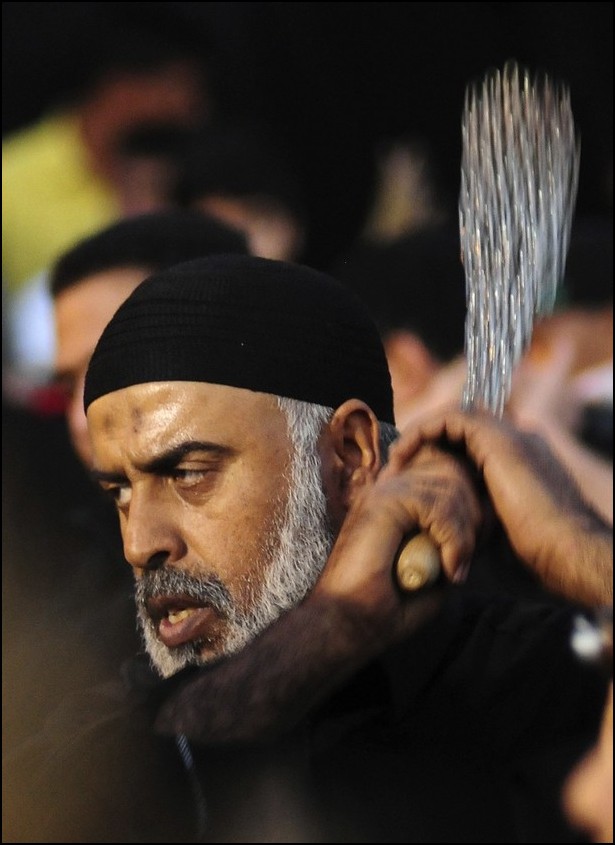

Certain traditional flagellation rituals such as Talwar zani (talwar ka matam or sometimes tatbir) use a sword. Other rituals, such as zanjeer zani or zanjeer matam, use a zanjeer (a chain with blades).[70] This can be controversial and some Shia clerics have denounced the practice saying «it creates a backward and negative image of their community.» Instead believers are encouraged to donate blood for those in need.[71] A few Shia Muslims observe the event by donating blood («Qame Zani»), and flagellating themselves[72]

-

Indian Shia Muslims carry out a Ta’ziya procession on day of Ashura in Barabanki, India, January 2009.

-

A historic Ashura celebration in Jamaica, which is known locally as Hussay or Hosay

-

Shia Muslims carry out an Al’am procession on the day of Ashura in Barabanki, India, January 2009.

-

Nakhl gardani in cities and villages of Iran

Socio-political aspects[edit]

Commemoration of Ashura is of great socio-political value to the Shia, who have been a minority throughout their history. According to the prevailing conditions at the time of the commemoration, such reminiscences may become the basis for implicit dissent or even explicit protest. This is what happened, for instance, during the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Lebanese Civil War, the Lebanese resistance against the Israeli military presence and in the 1990s Uprising in Bahrain. Sometimes Ashura commemorations overtly associate the memory of Al-Husayn’s martyrdom with the conditions of modern Islam and Muslims in reference to Husayn’s famous quote on the day of Ashura: «Every day is Ashura, every land is Karbala».[73]

From the period of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911) onward, mourning gatherings increasingly took on a political aspect, with preachers comparing the oppressors of the time with Imam Husayn’s enemies, the Umayyads.[74]

The political function of the commemorations was very marked in the years leading up to the Islamic Revolution of 1978–79, as well as during the revolution itself. In addition, the implicit self-identification of the Muslim revolutionaries with Imam Husayn led to a blossoming of the cult of the martyr, expressed most vividly, perhaps, in the vast cemetery of Behesht-e Zahra, to the south of Tehran, where the martyrs of the revolution and the war against Iraq are buried.[74]

On the other hand, some governments have banned this commemoration. In the 1930s Reza Shah forbade it in Iran. The regime of Saddam Hussein saw it as a potential threat and banned Ashura commemorations for many years.[75] During the 1884 Hosay massacre, 22 people were killed in Trinidad and Tobago when civilians attempted to carry out the Ashura rites, locally known as Hosay, in defiance of the British colonial authorities.[76]

Terrorist attacks during Ashura[edit]

Terrorist attacks against Shia Muslims have occurred in several countries on the day of Ashura, which has produced an «interesting» feedback effect in Shia history.[77]

- 1818–1820: Syed Ahmad Barelvi and Shah Ismail Dihlavi took up arms to stop the Ashura commemoration in North India. They were the pioneers of anti-Shia terrorism in the subcontinent. Barbara Metcalf noted:

A second group of abuses Syed Ahmad held were those that originated from Shi’i influence. He particularly urged Muslims to give up the keeping of ta’ziyahs, the replicas of the tombs of the martyrs of Karbala taken in procession during the mourning ceremony of Muharram. Muhammad Isma’il wrote, «a true believer should regard the breaking of a tazia by force to be as virtuous an action as destroying idols. If he cannot break them himself, let him order others to do so. If this even be out of his power, let him at least detest and abhor them with his whole heart and soul». Sayyid Ahmad himself is said, no doubt with considerable exaggeration, to have torn down thousands of imambaras, the building that house the taziyahs.[78]

- 1940: Bomb thrown on Ashura Procession in Delhi, 21 February[79]

- 1994: explosion of a bomb at the Imam Reza shrine, 20 June, in Mashhad, Iran, 20 people killed[80]

- 2004: bomb attacks, during Shia pilgrimage to Karbala, 2 March, Karbala, Iraq, 178 people killed and 5000 injured[81]

- 2008: clashes, between Iraqi troops and members of a Shia cult, 19 January, Basra and Nasiriya, Iraq, 263 people killed[82]

- 2009: explosion of a bomb, during the Ashura procession, 28 December, Karachi, Pakistan, dozens of people killed and hundreds injured[83]

- 2010: detention of 200 Shia Muslims, at a shop house in Sri Gombak known as Hauzah Imam Ali ar-Ridha (Hauzah ArRidha), 15 December, Selangor, Malaysia[84]

- 2011: explosion of a bomb, during the Ashura procession, 28 December, Hilla and Baghdad, Iraq, 5 December 30 people killed[85]

- 2011: suicide attack, during the Ashura procession, Kabul, Afghanistan, 6 December 63 people killed[86]

- 2015: three explosions, during the Ashura procession, mosque in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 24 October, one person killed and 80 people injured[87]

In the Gregorian calendar[edit]

While Ashura always takes place on the same day of the Islamic calendar, the date on the Gregorian calendar varies from year to year due to differences between the two calendars, since the Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar and the Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar. Furthermore, the appearance of the crescent moon used to determine when each Islamic month begins varies from country to country due to their different geographic locations.[citation needed]

| AH | Gregorian date |

|---|---|

| 1438 | 2016 October 12 (Middle East: Lebanon, Iraq, Iran) |

| 1439 | 2017 October 1 (Middle East: Lebanon, Iraq, Iran)[88] |

| 1440 | 2018 September 21 |

| 1441 | 2019 September 10 |

| 1442 | 2020 August 30[89] |

| 1443 | 2021 August 18[89] |

| 1444 | 2022 August 7[89] |

Gallery[edit]

-

Shias mourning in Iran

-

Shias mourning in Qatif, Saudi Arabia

-

Shias Muslims observing Ashura in Syria

-

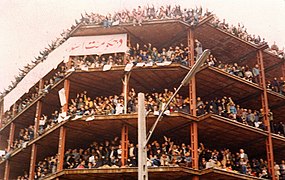

Ashura Demonstration in Tehran in 1978

-

2016 Ashura mourning in Imam Husayn Square

See also[edit]

- Al-Tall Al-Zaynabiyya

- Ashoura (missile)

- Ashura in Algeria

- Ashure

- Battle of Karbala

- Bibi-Ka-Alam

- Day of Tasu’a

- Hobson Jobson

- List of casualties in Husayn’s army at the Battle of Karbala

- Mourning of Muharram

- Passover

- Persecution of Shia Muslims

- Sebiba

- Yom Kippur

- Ziyarat Ashura

Notes[edit]

- ^ Except his young son, Ali, who was severely ill during that battle.[24]

- ^ Quran, 12:84

- ^ From Shaykh as-Sadooq, al-Khisal; quoted in al-Ameen, A’yan, IV, 195. The same is quoted from Bin Shahraashoob’s Manaqib in Bih’ar al-Anwar, XLVI, 108; cf. similar accounts, Ibid, pp. 108–10

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d «When is Ashura Day Worldwide». 30 September 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ «Holidays and observances in Iraq in 2022». www.timeanddate.com.

- ^ «Islamic Calendar». islamicfinder.

- ^ Morrow, John Andrew. Islamic Images and Ideas: Essays on Sacred Symbolism. McFarland & Co, 2013. pp. 234–36. ISBN 978-0786458486

- ^ «What is Ashura and how do Shia and Sunni Muslims observe it?». Middle East Eye. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Lipka, Michael; Ghani, Fatima. «Muslim holiday of Ashura brings into focus Shia-Sunni differences». Pew Research Center. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ «Dramatic photos show how Shiite Muslims mark Ashura, one of the most emotional events in Islam». The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ «Ashura | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ «Fasting in Muharram». Penny Appeal. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ M. Maarouf, 2010, Ashura and the Ritual Emancipation of Women in Morocco, CESNUR 2010

- ^ A. J. Wensinck, «Āshūrā», Encyclopaedia of Islam 2. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ a b «ʿĀshūrāʾ: Islamic holy day». Britannica.

- ^ «Ashura fasting in Muharram 2022: Date, history, significance of Shia and Sunni Muslims’ fast in Muharram». Hindustan Times. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 60, Hadith 70

- ^ Morrow, John Andrew. Islamic Images and Ideas: Essays on Sacred Symbolism. McFarland & Co, 2013. pp. 234–36. ISBN 978-0786458486

- ^ Katz, Marion Holmes The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam. Routledge, 2007. pp. 113–15. ISBN 978-1135983949

- ^ a b Prophet Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, Francis E. Peters, SUNY Press, 1994, p. 204.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 65, Hadith 31

- ^ «Virtues of fasting on Ashura».

- ^ Sahih at-Tirmidhi book 8 (in Arabic).

- ^ G.R., Hawting (2012). «Yazīd (I) b. Muʿāwiya». Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8000.

- ^ Hitti, Philip K. (1961). The Near East in History A 5000 Year Story. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1258452452. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Madelung, Wilferd. «Ḥisayn B. ‘Ali i. Life and Significance in Shi’ism». Encyclopædia Iranica Online. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ Hoseini-e Jalali, Mohammad-Reza (1382). Jehad al-Imam al-Sajjad (in Persian). Translated by Musa Danesh. Iran, Mashhad: Razavi, Printing & Publishing Institute. pp. 214–17.

- ^ «در روز عاشورا چند نفر شهید شدند؟». Archived from the original on 26 March 2013.

- ^ «فهرست اسامي شهداي كربلا». Velaiat.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter J. (1979). Ta’ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran. New York. p. 2.

- ^ Madelung, Wilferd. «ʿAlī B. Ḥosayn B. ʿAlī B. Abī Tāleb». Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi’ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. Burleigh Press. pp. 101–11.

- ^ «Zaynab Bint Ali». Encyclopedia of Religion. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ Goldziher, Ignác (1981). Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law. Princeton. p. 179. ISBN 9780691100999.

- ^ Sharif al-Qarashi, Bāqir (2000). The Life of Imām Zayn al-Abidin (as). Translated by Jāsim al-Rasheed. Iraq: Ansariyan Publications, n.d. Print.

- ^ Imam Ali ubnal Husain (2009). Al-Saheefah Al-Sajjadiyyah Al-Kaamelah. Translated with an Introduction and annotation by Willian C. Chittick With a foreword by S. H. M. Jafri. Qum, The Islamic Republic of Iran: Ansariyan Publications.

- ^ a b «Hosayn B. Ali in Popular Shiism». Encyclopedia of Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ al Musawi, 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Litvak, 1998, p. 16.

- ^ Nafasul Mahmoom. JAC Developer. pp. 12–. GGKEY:RQAZ12CNGF5.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter (1 January 1985). «Shia Muslim Processional Performances». The Drama Review: TDR. 29 (3): 18–30. doi:10.2307/1145650. JSTOR 1145650.

- ^ Blank, Jonah (15 April 2001). Mullahs on the Mainframe: Islam and Modernity Among the Daudi Bohras. University of Chicago Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0226056777.

- ^ Turkish Alevis are mourning on this day for the remembrance of the death of Huseyn bin Ali at Kerbala in Irak.

- ^ Turkish Alevis mourn on this day to commemorate the death of Huseyn bin Ali at Kerbala in Irak.

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J.; Kamran Scot Aghaie (2007). Voices of Islam. Westport, CN: Praeger Publishers. pp. 111–12. ISBN 978-0275987329. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ «Karbala’, an Enduring Paradigm». Al-islam.org. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Dabashi, Hamid (2008). Islamic Liberation Theology: Resisting the Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415771559.

- ^ Ayoub, Shi’ism (1988), pp. 258–59

- ^ Juan Eduardo Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. pp. 318–. ISBN 978-1438126968.

- ^ প্রতিবেদক, নিজস্ব (13 September 2019). «কারবালা দিবস উপলক্ষে বিশ্ব সুন্নি আন্দোলন, যুক্তরাষ্ট্রের সমাবেশ». Prothomalo (in Bengali). Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Jean, Calmard (2011). «AZĀDĀRĪ». iranicaonline.

- ^ Bird, Steve (28 August 2008). «Devout Muslim guilty of making boys beat themselves during Shia ceremony». The Times. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ «British Muslim convicted over teen floggings». Alarabiya.net. 27 August 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ «1 million pilgrims perform Tuwairij rush in Karbala». Aswat al-Iraq. 27 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ «مراسم «هروله طویریج»؛ یکی از عظیم ترین گردهمایی های جهان». میدل ایست نیوز (in Persian). 31 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «‘Tuwairij run’ takes place in Holy city of Karbala, Iraq». iranpress.com. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «حماسی ترین مراسم عاشورایی در كربلا آغاز شد». ایرنا (in Persian). 1 October 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ «تجلی عشق حسینی در » رَکْضَة طُوَیرِیج ««. shooshan.ir. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «داستان دسته طويريج چیست؟ + تصاویر». مشرق نیوز (in Persian). 17 November 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Nawaret (8 December 2011). «ماهي ركضة طويريج في العراق». جريدة نورت (in Arabic). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «أصل-ركضة-طويريج-ومنشؤها».

- ^ «عزاء ركضة طويريج نشأته وتاريخه». شيعة ويفز – ShiaWaves Arabic (in Arabic). 19 September 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «تاریخچهای از دسته عزاداری طویریج – کرب و بلا». سایت تخصصی امام حسین علیه السلام (in Persian). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «ركضة طويريج .. من أكبر الفعاليات الدينية في العالم.. تعرف على تأريخها». almasalah.com. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ a b Nakash, Yitzhak (1 January 1993). «An Attempt To Trace the Origin of the Rituals of Āshurā¸». Die Welt des Islams. 33 (2): 161–81. doi:10.1163/157006093X00063. – via Brill (subscription required)

- ^ David Pinault, «Shia Lamentation Rituals and Reinterpretations of the Doctrine of Intercession: Two Cases from Modern India,» History of Religions 38 no. 3 (1999): 285–305.

- ^ Nasr, Vali, «The Shia Revival», Norton, 2006, p. 50

- ^ Puchowski, Douglas (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415994040.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter (ed.) (1979) Taʻziyeh, ritual and drama in Iran New York University Press, New York, ISBN 0814713750

- ^ Ali, Alim (14 February 2009). «Hosay Festival, Westmoreland, Jamaica».

- ^ http://old.jamaica-gleaner.com/pages/history/story0057.htm title= Out Of Many Cultures The People Who Came The Arrival Of The Indians

- ^ Rezaian, Jason. «Iranians relish free food during month of mourning». washingtonpost.

- ^ «Scars on the backs of the young». New Statesman. UK. 6 June 2005. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ «Ashoura day: Why Muslims fast and mourn on Muharram 10». Al Jazeera. 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Ashura observed with blood streams to mark Karbala tragedy». Jafariya News Network. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ «Observing Salat Behind a Shiite Imam». Fiqh. 22 May 2022. Archived from the original on 11 December 2006.

- ^ a b Calmard, J. «‘Azaúdaúrè». Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010). Religions of the World [6 volumes]: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. p. 211. ISBN 978-1598842036.

- ^ Anthony, Michael (2001). Historical Dictionary of Trinidad and Tobago. Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, MD and London. ISBN 978-0810831735.

- ^ Hassner, Ron E. (2016). Religion on the Battlefield. Cornell University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0801451072.

Violence during Ashura.

- ^ B. Metcalf, Islamic revival in British India: Deoband, 1860–1900, p. 58, Princeton University Press (1982).

- ^ J. N. Hollister, The Shi’a of India, p. 178, Luzac and Co, London, (1953).

- ^ Raman, B. (7 January 2002). «Sipah-E-Sahaba Pakistan, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Bin Laden & Ramzi Yousef». Archived from the original on 29 April 2009.

- ^ «Blasts at Shia Ceremonies in Iraq Kill More Than 140». The New York Times. 2 March 2004. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ «Iraqi Shia pilgrims mark holy day». bbc.co.uk. 19 January 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ «Reuters News clip». Youtube.com. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ «Malaysian Wahhabi Extremists Attacked Shia Mourners, Detain 200 + PIC». abna.ir. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ «Deadly bomb attacks on Shia pilgrims in Iraq». bbc.co.uk. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Harooni, Mirwais (6 December 2011). «Blasts across Afghanistan target Shia, 59 dead». Reuters. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ «Dhaka blasts: One dead in attack on Shia Ashura ritual». BBC News. 24 October 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ «Holidays in Iran in 2017».

- ^ a b c «Ashura – Calendar Date». www.calendardate.com. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

Sources[edit]

- Litvak, Meir (1998). Shi’i Scholars of Nineteenth-Century Iraq: The Ulama of Najaf and Karbala. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89296-1

- al Musawi, Muhsin (2006). Reading Iraq: Culture and Power and Conflict. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-070-6

- al Mufid, al-Shaykh Muhammad (December 1982 (1st ed.)). Kitab Al-Irshad. Tahrike Tarsile Quran. ISBN 0-940368-12-9, 978-0-940368-12-5

- al-Azdi, abu Mikhnaf, Maqtal al-Husayn. Shia Ithnasheri Community of Middlesex (PDF)

Further reading[edit]

- Sivan, Emmanuel (1989). «Sunni Radicalism in the Middle East and the Iranian Revolution». International Journal of Middle East Studies. 21 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1017/S0020743800032086. JSTOR 163637. S2CID 162459682.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashura.

- Gordon B. Coutts (Scottish/American, 1868–1937) A Large Oil on Canvas Depicting «The Ashura Rituals, Tangier» (Arabic: عاشوراء ʻĀshūrā’ – Urdu: عاشورا – Persian: عاشورا – Turkish: Aşure Günü). Signed and inscribed: ‘Gordon Coutts/TANGIER (lower right). c. 1920

- Is Aashura a day of mourning or rejoicing?

- Ashura – The Historical Significance and Rewards on Islam Freedom

- Events on the day of Ashura

- «Ashura» An article in Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- What is Ashura? (BBC News)

- What Is Ashura? – by Abdul-Ilah As-Saadi on Al Jazeera

- Ashura Australia – Official website of the Annual Ashura Procession in Sydney

This article is about the Islamic holy day. For the traditional dessert, see Ashure. For other uses, see Ashura (disambiguation).

| Ashura عَاشُورَاء |

|

|---|---|

Procession for Ashura at Imam Hossein Square in Tehran, Iran (2016) |

|

| Type | Islamic (Shia and Sunni) |

| Significance | In Shia Islam: Mourning the death of Husayn ibn Ali during the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE In Sunni Islam: Celebrating the salvation of Moses and the Israelites from their enslavement in Biblical Egypt |

| Observances |

|

| Date | 10 Muharram |

| 2022 date | 8 August[1] |

| Frequency | Annual (Islamic calendar) |

Ashura (Arabic: عَاشُورَاء, ʿĀshūrāʾ, [ʕaːʃuːˈraːʔ]) is a day of commemoration in Islam. It occurs annually on the 10th of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar. Among Shia Muslims, Ashura is observed through large demonstrations of high-scale mourning as it marks the death of Husayn ibn Ali (a grandson of Muhammad), who was beheaded during the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE.[4] Among Sunni Muslims, Ashura is observed through celebratory fasting as it marks the day of salvation for Moses and the Israelites, who successfully escaped from Biblical Egypt (where they were enslaved and persecuted) after Moses called upon God’s power to part the Red Sea.[5] While Husayn’s death is also regarded as a great tragedy by Sunnis, open displays of mourning are either discouraged or outright prohibited, depending on the specific act.[6]

In Shia communities, Ashura observances are typically carried out in group processions and are accompanied by a variety of rituals ranging from weeping and shrine pilgrimages to the more controversial acts of self-flagellation and chest-beating.[7] In Sunni communities, there are three rounds of fasting, based on Muhammad’s hadith: on the day before Ashura, on the day of Ashura, and on the day after Ashura; while fasting for Ashura is not obligatory, it is strongly encouraged.[8][9] In folk traditions across countries such as Morocco and Algeria, the day of Ashura is variously celebrated with special foods, bonfires, or carnivals, though these practices are not supported by religious authorities.[10] Due to the drastically differing methods of observance between Sunnis and Shias, the day of Ashura has come to acquire a political dimension in some Islamic countries, and particularly in Iran, where Shia Islam is the official state religion. Additionally, it has also served as a trigger for controversy as well as violent incidents between the two communities in countries such as Iraq and Pakistan.

Etymology[edit]

The root of the word Ashura means tenth in Semitic languages; hence the name, literally translated, means «the tenth day». According to the Islamicist A. J. Wensinck, the name is derived from the Hebrew ʿāsōr, with the Aramaic determinative ending.[11]

Origin[edit]

Sunni Islam[edit]

Fasting on Ashura, the tenth day of the Islamic month of Muharram was a practice established by Muhammad in the early days of Islam that commemorates the parting of the Red Sea by Moses.[12][13] Its beginning is recounted in a sahih hadith recorded through Ibn Abbas by al-Bukhari:

When the Prophet (ﷺ) came to Medina, he found (the Jews) fasting on the day of ‘Ashura’ (i.e. 10th of Muharram). They used to say: «This is a great day on which Allah saved Moses and drowned the folk of Pharaoh. Moses observed the fast on this day, as a sign of gratitude to Allah.» The Prophet (ﷺ) said, «I am closer to Moses than they.» So, he observed the fast (on that day) and ordered the Muslims to fast on it.[14]

This has been analysed as reflecting an encounter between Muhammad and some Jews fasting for Yom Kippur, on the tenth day of Tishri, in commemoration of Moses, upon which he began to fast on that day and instruct fellow Muslims to fast.[15][16] The practice would thus have been established at a time when the Islamic and Jewish calendars were synced.[17] However, Muhammad later received a revelation to adjust the Islamic calendar, in the verse of Nasi’, and with this Ramadan, the ninth month, became the month of fasting, and the obligation to fast on Ashura was dropped, as Ashura became distinct from its Jewish predecessor of Yōm Kippur.[12][17] According to a sahih hadith narrated through Aisha:

During the Pre-lslamic Period of ignorance the Quraish used to observe fasting on the day of ‘Ashura’, and the Prophet (ﷺ) himself used to observe fasting on it too. But when he came to Medina, he fasted on that day and ordered the Muslims to fast on it. When (the order of compulsory fasting in) Ramadan was revealed, fasting in Ramadan became an obligation, and fasting on ‘Ashura’ was given up, and who ever wished to fast (on it) did so, and whoever did not wish to fast on it, did not fast.[18]

It is still widely considered desirable (mustahab) to fast on Ashura (10th day), and also on Tasua (9th day).[19] With hadith in Jami At-Tirmidhi signifying that God forgives the sins of the year prior for people fasting Ashura.[20]

Shia Islam[edit]

Martyrdom of Ḥusayn[edit]

Millions of Shia Muslims gather around the Husayn Mosque in Karbala after making the pilgrimage on foot during Arba’een, which is a Shia religious observation that occurs 40 days after the Day of Ashura.

The Battle of Karbala took place during the period of decay resulting from the succession of Yazid I.[21][22] Immediately after his succession, Yazid instructed the governor of Medina to compel Ḥusayn and a few other prominent figures to pledge their allegiance (Bay’ah).[23] However, Ḥusayn refused to do this, believing that Yazid was going against the teachings of Islam and changing the sunnah of Muhammad.[citation needed] So, accompanied by his household, his sons, brothers, and the sons of Hasan, he left Medina to seek asylum in Mecca.[23]

In Mecca, Ḥusayn learned that Yazid had sent assassins to kill him during the Hajj. To preserve the sanctity of the city and of the Kaaba, Husayn abandoned his Hajj and encouraged his companions to follow him to Kufa without realising that the situation there had taken an adverse turn.[23]

On the way there, Ḥusayn found that his messenger, Muslim ibn Aqeel, had been killed in Kufa and encountered the vanguard of the army of Ubaydullah ibn Ziyad. Ḥe addressed the Kufan army, reminding them that they had invited him to come there because they were without an Imam, and told them that he intended to proceed to Kufa with their support; however, if they were now opposed to his coming, he would return to Mecca. When the army urged him to take another route, he turned to the left and reached Karbala, where the army forced him to stop at a location with little water.[23]

Governor Ubaydullah ibn Ziyad instructed Umar ibn Sa’ad, the head of the Kufan army, to again offer Ḥusayn and his supporters the opportunity to swear allegiance to Yazid. He also ordered Umar ibn Sa’ad to cut Ḥusayn and his followers off from access to the water of the Euphrates.[23] The next morning, Umar ibn Sa’ad arranged the Kufan army in battle formation.[23]

The Battle of Karbala lasted from sunrise to sunset on 10 October 680 (Muharram 10, 61 AH). Husayn’s small group of companions and family members (around 72 men plus women and children)[note 1][25][26] fought against Umar ibn Sa’ad’s army and were killed near the Euphrates, from which they were not allowed to drink. The renowned historian Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī states:

… [T]hen fire was set to their camp and the bodies were trampled by the hoofs of the horses; nobody in the history of the human kind has seen such atrocities.[27]

Once the Umayyad troops had murdered Ḥusayn and his male followers, they looted the tents, stripped the women of their jewellery, and took the skin upon which Zain al-Abidin was prostrate. Ḥusayn’s sister Zaynab was taken along with the enslaved women to the king in Damascus where she was imprisoned before being allowed to return to Medina after a year.[28][29]

Significance[edit]

The first assembly (majlis) of the Commemoration of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī is said to have been held by Zaynab in prison. In Damascus she is also reported to have delivered a poignant oration. The prison sentence ended when Husayn’s four-year-old daughter, Ruqayyah bint Husayn, who would often cry to be allowed to see her father, died in captivity, probably after seeing his mutilated head. Her death caused an uproar in the city, and, fearing an uprising, Yazid freed the captives.[30]

According to Ignác Goldziher,

Ever since the black day of Karbala, the history of this family … has been a continuous series of sufferings and persecutions. These are narrated in poetry and prose, in a richly cultivated literature of martyrologies … ‘More touching than the tears of the Shi’is’ has even become an Arabic proverb.[31]

Imam Zayn Al Abidin said the following:

It is said that for forty years whenever food was placed before him, he would weep. One day a servant said to him, ‘O son of Allah’s Messenger! Is it not time for your sorrow to come to an end?’ He replied, ‘Woe upon you! Jacob the prophet had twelve sons, and Allah made one of them disappear. His eyes turned white from constant weeping, his head turned grey out of sorrow, and his back became bent in gloom,[note 2] though his son was alive in this world. But I watched while my father, my brother, my uncle, and seventeen members of my family were slaughtered all around me. How should my sorrow come to an end?’[note 3][32][33]

Husayn’s grave became a pilgrimage site for Shia Muslims within a few years of his death. A tradition of pilgrimage to the shrine of Imam Husayn and the other Karbala martyrs, known as Ziarat ashura, quickly developed.[34] The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs tried to prevent construction of the shrines and discouraged pilgrimage.[35] The tomb and its annexes were destroyed by the Abbasid caliph Al-Mutawakkil in 850–851 and Shia pilgrimage was prohibited, but shrines in Karbala and Najaf were built by the Buwayhid emir ‘Adud al-Daula in 979–80.[36]

Public rites of remembrance for Husayn’s martyrdom developed from the early pilgrimages.[37] Under the Buyid dynasty, Mu’izz ad-Dawla officiated at a public commemoration of Ashura in Baghdad.[38] These commemorations were also encouraged in Egypt by the Fatimid caliph al-‘Aziz.[39] With the recognition of the Twelvers as the official religion by the Safavids, the Mourning of Muharram extended throughout the first ten days of Muharram.[34]

Ashura was remembered by Jafaris, Qizilbash Alevi-Turks, and Bektashis during the period of the Ottoman Empire.[41] It is of particular significance to Twelver Shias and Alawites, who consider Husayn (the grandson of Muhammad) Ahl al-Bayt, the third Imam to be the rightful successor of Muhammad.[citation needed]

According to Kamran Scot Aghaie, «The symbols and rituals of Ashura have evolved over time and have meant different things to different people. However, at the core of the symbolism of Ashura is the moral dichotomy between worldly injustice and corruption on the one hand and God-centered justice, piety, sacrifice and perseverance on the other. Also, Shiite Muslims consider the remembrance of the tragic events of Ashura to be an important way of worshipping God in a spiritual or mystical way.»[42]

Shia Muslims make pilgrimages on Ashura, as they do forty days later on ʾArbaʿīn, to the Mashhad al-Husayn, the shrine in Karbala, Iraq, that is traditionally held to be Husayn’s tomb. This is a day of remembrance, and mourning attire is worn. This is a time for sorrow and for showing respect for the person’s passing, and it is also a time for self-reflection when a believer commits themself completely to the mourning of Husayn. Shia Muslims refrain from listening to or playing music since Arabic culture generally considers playing music during death rituals to be impolite. Nor do they plan weddings or parties on this date. Instead they mourn by crying and listening to recollections of the tragedy and sermons on how Husayn and his family were martyred. This is intended to connect them with Husayn’s suffering and martyrdom, and the sacrifices he made to keep Islam alive. Husayn’s martyrdom is widely interpreted by Shia Muslims as a symbol of the struggle against injustice, tyranny, and oppression.[43] Shia Muslims believe the Battle of Karbala was between the forces of good and evil, with Husayn representing good and Yazid representing evil.[44]

Shia imams insist that Ashura should not be celebrated as a day of joy and festivity. According to the Eighth Shia Imam Ali al-Rida, it must be observed as a day of rest, sorrow, and total disregard of worldly matters.[45]

Some of the events associated with Ashura are held in special congregation halls known as «Imambargah» and Hussainia.[46]

The World Sunni Movement celebrates this day as the National Martyrs’ Day of the Muslim nation under the direction of Syed Imam Hayat.[47]

Remembrance[edit]

Azadari (mourning) rituals[edit]

The words Azadari (Persian: عزاداری), which means mourning and lamentation, and Majalis-e Aza are used exclusively in connection with the remembrance ceremonies for the martyrdom of Imam Hussain. Majalis-e Aza, also known as Aza-e Husayn, includes mourning congregations, lamentations, matam and all acts which express the grief and, above all, repulsion against what Yazid stood for.[48]

Ritual scourge for use in the Ashura procession. Syria, before 1974

These customs show solidarity with Husayn and his family. Through them, people mourn Husayn’s death and express regret for the fact that they were not present at the battle to save Husayn and his family.[49][50]

Tuwairij run[edit]

The Tuwairij run is the name of an Ashura ceremony in which millions of people from around Tuwairij in 22 km run and mourning on side of the Imam Husayn Shrine.[51] this ceremony is considered as the biggest observance of religious activities in the world.[52][53] Its importance has grown since Moḥammad Mahdī Baḥr al-ʿUlūm was quoted as saying that Hujjat bin Hasan was present at this ceremony.[54]

History[edit]

The Tuwairij was first run on Ashura 1855 when people who were at the house of Seyyed Saleh Qazvini after the mourning ceremony and the recitation of the murder of Husain bin ‘Ali cried so much from grief and sorrow that they asked Seyyed Saleh to run to the imam’s shrine to offer his condolences. Seyyed Saleh accepted their request and went to the shrine with all the mourners.[55][56][57][58]

Prohibition of the march[edit]

The march was banned by Saddam Hussein’s Ba‘athist regime between 1991 and 2003.[59][60] However, despite the ban, Tuwairij still continued and the regime executed many participants.[citation needed] The event was permitted again after 2003, and participation from outside Iraq has steadily increased.[61]

Popular customs[edit]

After almost 12 centuries, five main types of rituals were developed around the story of the battle of Karbala. These rituals include memorial services (majalis al-ta’ziya); visits to Husayn’s tomb in Karbala particularly on Ashura and on the fortieth day after the battle (Ziyarat Ashura and Ziyarat al-Arba’in); public mourning processions (al-mawakib al-husayniyya); representation of the battle as a play (the shabih); and personal flagellation (tatbir).[62] Some Shia Muslims believe that taking part in Ashura washes away their sins.[63] A popular Shia saying has it that «a single tear shed for Husayn washes away a hundred sins».[64]

For Shia Muslims, the commemoration of Ashura is an event of intense grief and mourning. Mourners congregate at a mosque for sorrowful, poetic recitations such as marsiya, noha, latmiya, and soaz performed in memory of the martyrdom of Husayn, lamenting and grieving to the tune of beating drums and chants of «Ya Hussain». Ulamas also give sermons on the themes of Husayn’s personality and position in Islam, and the history of his uprising. The Sheikh of the mosque retells the story of the Battle of Karbala to allow his listeners to relive the pain and sorrow endured by Husayn and his family and they read Maqtal Al-Husayn.[62][65] In some places, such as Iran, Iraq, and the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, passion plays known as Ta’zieh[66] are performed, reenacting the Battle of Karbala and the suffering and martyrdom of Husayn at the hands of Yazid.

In the Caribbean islands of Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica, Ashura, known locally as ‘Hussay’ or Hosay, may commemorate the grandson of Muhammad, but the celebration has taken on influences from other religions including Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, and the Baptist movement, so that it has become a mixture of different cultures and religion. The event is attended by both Muslims and non-Muslims in an environment of mutual respect and tolerance.[67][68] For the duration of the memorial events, it is customary for mosques and individuals to provide free meals (Nazri or Votive Food) for everyone on certain nights.[69]

Certain traditional flagellation rituals such as Talwar zani (talwar ka matam or sometimes tatbir) use a sword. Other rituals, such as zanjeer zani or zanjeer matam, use a zanjeer (a chain with blades).[70] This can be controversial and some Shia clerics have denounced the practice saying «it creates a backward and negative image of their community.» Instead believers are encouraged to donate blood for those in need.[71] A few Shia Muslims observe the event by donating blood («Qame Zani»), and flagellating themselves[72]

-

Indian Shia Muslims carry out a Ta’ziya procession on day of Ashura in Barabanki, India, January 2009.

-

A historic Ashura celebration in Jamaica, which is known locally as Hussay or Hosay

-

Shia Muslims carry out an Al’am procession on the day of Ashura in Barabanki, India, January 2009.

-

Nakhl gardani in cities and villages of Iran

Socio-political aspects[edit]

Commemoration of Ashura is of great socio-political value to the Shia, who have been a minority throughout their history. According to the prevailing conditions at the time of the commemoration, such reminiscences may become the basis for implicit dissent or even explicit protest. This is what happened, for instance, during the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Lebanese Civil War, the Lebanese resistance against the Israeli military presence and in the 1990s Uprising in Bahrain. Sometimes Ashura commemorations overtly associate the memory of Al-Husayn’s martyrdom with the conditions of modern Islam and Muslims in reference to Husayn’s famous quote on the day of Ashura: «Every day is Ashura, every land is Karbala».[73]

From the period of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911) onward, mourning gatherings increasingly took on a political aspect, with preachers comparing the oppressors of the time with Imam Husayn’s enemies, the Umayyads.[74]

The political function of the commemorations was very marked in the years leading up to the Islamic Revolution of 1978–79, as well as during the revolution itself. In addition, the implicit self-identification of the Muslim revolutionaries with Imam Husayn led to a blossoming of the cult of the martyr, expressed most vividly, perhaps, in the vast cemetery of Behesht-e Zahra, to the south of Tehran, where the martyrs of the revolution and the war against Iraq are buried.[74]

On the other hand, some governments have banned this commemoration. In the 1930s Reza Shah forbade it in Iran. The regime of Saddam Hussein saw it as a potential threat and banned Ashura commemorations for many years.[75] During the 1884 Hosay massacre, 22 people were killed in Trinidad and Tobago when civilians attempted to carry out the Ashura rites, locally known as Hosay, in defiance of the British colonial authorities.[76]

Terrorist attacks during Ashura[edit]

Terrorist attacks against Shia Muslims have occurred in several countries on the day of Ashura, which has produced an «interesting» feedback effect in Shia history.[77]

- 1818–1820: Syed Ahmad Barelvi and Shah Ismail Dihlavi took up arms to stop the Ashura commemoration in North India. They were the pioneers of anti-Shia terrorism in the subcontinent. Barbara Metcalf noted:

A second group of abuses Syed Ahmad held were those that originated from Shi’i influence. He particularly urged Muslims to give up the keeping of ta’ziyahs, the replicas of the tombs of the martyrs of Karbala taken in procession during the mourning ceremony of Muharram. Muhammad Isma’il wrote, «a true believer should regard the breaking of a tazia by force to be as virtuous an action as destroying idols. If he cannot break them himself, let him order others to do so. If this even be out of his power, let him at least detest and abhor them with his whole heart and soul». Sayyid Ahmad himself is said, no doubt with considerable exaggeration, to have torn down thousands of imambaras, the building that house the taziyahs.[78]

- 1940: Bomb thrown on Ashura Procession in Delhi, 21 February[79]

- 1994: explosion of a bomb at the Imam Reza shrine, 20 June, in Mashhad, Iran, 20 people killed[80]

- 2004: bomb attacks, during Shia pilgrimage to Karbala, 2 March, Karbala, Iraq, 178 people killed and 5000 injured[81]

- 2008: clashes, between Iraqi troops and members of a Shia cult, 19 January, Basra and Nasiriya, Iraq, 263 people killed[82]

- 2009: explosion of a bomb, during the Ashura procession, 28 December, Karachi, Pakistan, dozens of people killed and hundreds injured[83]

- 2010: detention of 200 Shia Muslims, at a shop house in Sri Gombak known as Hauzah Imam Ali ar-Ridha (Hauzah ArRidha), 15 December, Selangor, Malaysia[84]

- 2011: explosion of a bomb, during the Ashura procession, 28 December, Hilla and Baghdad, Iraq, 5 December 30 people killed[85]

- 2011: suicide attack, during the Ashura procession, Kabul, Afghanistan, 6 December 63 people killed[86]

- 2015: three explosions, during the Ashura procession, mosque in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 24 October, one person killed and 80 people injured[87]

In the Gregorian calendar[edit]

While Ashura always takes place on the same day of the Islamic calendar, the date on the Gregorian calendar varies from year to year due to differences between the two calendars, since the Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar and the Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar. Furthermore, the appearance of the crescent moon used to determine when each Islamic month begins varies from country to country due to their different geographic locations.[citation needed]

| AH | Gregorian date |

|---|---|

| 1438 | 2016 October 12 (Middle East: Lebanon, Iraq, Iran) |

| 1439 | 2017 October 1 (Middle East: Lebanon, Iraq, Iran)[88] |

| 1440 | 2018 September 21 |

| 1441 | 2019 September 10 |

| 1442 | 2020 August 30[89] |

| 1443 | 2021 August 18[89] |

| 1444 | 2022 August 7[89] |

Gallery[edit]

-

Shias mourning in Iran

-

Shias mourning in Qatif, Saudi Arabia

-

Shias Muslims observing Ashura in Syria

-

Ashura Demonstration in Tehran in 1978

-

2016 Ashura mourning in Imam Husayn Square

See also[edit]

- Al-Tall Al-Zaynabiyya

- Ashoura (missile)

- Ashura in Algeria

- Ashure

- Battle of Karbala

- Bibi-Ka-Alam

- Day of Tasu’a

- Hobson Jobson

- List of casualties in Husayn’s army at the Battle of Karbala

- Mourning of Muharram

- Passover

- Persecution of Shia Muslims

- Sebiba

- Yom Kippur

- Ziyarat Ashura

Notes[edit]

- ^ Except his young son, Ali, who was severely ill during that battle.[24]

- ^ Quran, 12:84

- ^ From Shaykh as-Sadooq, al-Khisal; quoted in al-Ameen, A’yan, IV, 195. The same is quoted from Bin Shahraashoob’s Manaqib in Bih’ar al-Anwar, XLVI, 108; cf. similar accounts, Ibid, pp. 108–10

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d «When is Ashura Day Worldwide». 30 September 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ «Holidays and observances in Iraq in 2022». www.timeanddate.com.

- ^ «Islamic Calendar». islamicfinder.

- ^ Morrow, John Andrew. Islamic Images and Ideas: Essays on Sacred Symbolism. McFarland & Co, 2013. pp. 234–36. ISBN 978-0786458486

- ^ «What is Ashura and how do Shia and Sunni Muslims observe it?». Middle East Eye. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Lipka, Michael; Ghani, Fatima. «Muslim holiday of Ashura brings into focus Shia-Sunni differences». Pew Research Center. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ «Dramatic photos show how Shiite Muslims mark Ashura, one of the most emotional events in Islam». The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ «Ashura | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ «Fasting in Muharram». Penny Appeal. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ M. Maarouf, 2010, Ashura and the Ritual Emancipation of Women in Morocco, CESNUR 2010

- ^ A. J. Wensinck, «Āshūrā», Encyclopaedia of Islam 2. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ a b «ʿĀshūrāʾ: Islamic holy day». Britannica.

- ^ «Ashura fasting in Muharram 2022: Date, history, significance of Shia and Sunni Muslims’ fast in Muharram». Hindustan Times. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 60, Hadith 70

- ^ Morrow, John Andrew. Islamic Images and Ideas: Essays on Sacred Symbolism. McFarland & Co, 2013. pp. 234–36. ISBN 978-0786458486

- ^ Katz, Marion Holmes The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam. Routledge, 2007. pp. 113–15. ISBN 978-1135983949

- ^ a b Prophet Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, Francis E. Peters, SUNY Press, 1994, p. 204.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 65, Hadith 31

- ^ «Virtues of fasting on Ashura».

- ^ Sahih at-Tirmidhi book 8 (in Arabic).

- ^ G.R., Hawting (2012). «Yazīd (I) b. Muʿāwiya». Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8000.

- ^ Hitti, Philip K. (1961). The Near East in History A 5000 Year Story. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1258452452. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Madelung, Wilferd. «Ḥisayn B. ‘Ali i. Life and Significance in Shi’ism». Encyclopædia Iranica Online. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ Hoseini-e Jalali, Mohammad-Reza (1382). Jehad al-Imam al-Sajjad (in Persian). Translated by Musa Danesh. Iran, Mashhad: Razavi, Printing & Publishing Institute. pp. 214–17.

- ^ «در روز عاشورا چند نفر شهید شدند؟». Archived from the original on 26 March 2013.

- ^ «فهرست اسامي شهداي كربلا». Velaiat.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter J. (1979). Ta’ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran. New York. p. 2.

- ^ Madelung, Wilferd. «ʿAlī B. Ḥosayn B. ʿAlī B. Abī Tāleb». Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi’ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. Burleigh Press. pp. 101–11.

- ^ «Zaynab Bint Ali». Encyclopedia of Religion. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ Goldziher, Ignác (1981). Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law. Princeton. p. 179. ISBN 9780691100999.

- ^ Sharif al-Qarashi, Bāqir (2000). The Life of Imām Zayn al-Abidin (as). Translated by Jāsim al-Rasheed. Iraq: Ansariyan Publications, n.d. Print.

- ^ Imam Ali ubnal Husain (2009). Al-Saheefah Al-Sajjadiyyah Al-Kaamelah. Translated with an Introduction and annotation by Willian C. Chittick With a foreword by S. H. M. Jafri. Qum, The Islamic Republic of Iran: Ansariyan Publications.

- ^ a b «Hosayn B. Ali in Popular Shiism». Encyclopedia of Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ al Musawi, 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Litvak, 1998, p. 16.

- ^ Nafasul Mahmoom. JAC Developer. pp. 12–. GGKEY:RQAZ12CNGF5.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter (1 January 1985). «Shia Muslim Processional Performances». The Drama Review: TDR. 29 (3): 18–30. doi:10.2307/1145650. JSTOR 1145650.

- ^ Blank, Jonah (15 April 2001). Mullahs on the Mainframe: Islam and Modernity Among the Daudi Bohras. University of Chicago Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0226056777.

- ^ Turkish Alevis are mourning on this day for the remembrance of the death of Huseyn bin Ali at Kerbala in Irak.

- ^ Turkish Alevis mourn on this day to commemorate the death of Huseyn bin Ali at Kerbala in Irak.

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J.; Kamran Scot Aghaie (2007). Voices of Islam. Westport, CN: Praeger Publishers. pp. 111–12. ISBN 978-0275987329. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ «Karbala’, an Enduring Paradigm». Al-islam.org. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Dabashi, Hamid (2008). Islamic Liberation Theology: Resisting the Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415771559.

- ^ Ayoub, Shi’ism (1988), pp. 258–59

- ^ Juan Eduardo Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. pp. 318–. ISBN 978-1438126968.

- ^ প্রতিবেদক, নিজস্ব (13 September 2019). «কারবালা দিবস উপলক্ষে বিশ্ব সুন্নি আন্দোলন, যুক্তরাষ্ট্রের সমাবেশ». Prothomalo (in Bengali). Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Jean, Calmard (2011). «AZĀDĀRĪ». iranicaonline.

- ^ Bird, Steve (28 August 2008). «Devout Muslim guilty of making boys beat themselves during Shia ceremony». The Times. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ «British Muslim convicted over teen floggings». Alarabiya.net. 27 August 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ «1 million pilgrims perform Tuwairij rush in Karbala». Aswat al-Iraq. 27 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ «مراسم «هروله طویریج»؛ یکی از عظیم ترین گردهمایی های جهان». میدل ایست نیوز (in Persian). 31 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «‘Tuwairij run’ takes place in Holy city of Karbala, Iraq». iranpress.com. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «حماسی ترین مراسم عاشورایی در كربلا آغاز شد». ایرنا (in Persian). 1 October 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ «تجلی عشق حسینی در » رَکْضَة طُوَیرِیج ««. shooshan.ir. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «داستان دسته طويريج چیست؟ + تصاویر». مشرق نیوز (in Persian). 17 November 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Nawaret (8 December 2011). «ماهي ركضة طويريج في العراق». جريدة نورت (in Arabic). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «أصل-ركضة-طويريج-ومنشؤها».

- ^ «عزاء ركضة طويريج نشأته وتاريخه». شيعة ويفز – ShiaWaves Arabic (in Arabic). 19 September 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «تاریخچهای از دسته عزاداری طویریج – کرب و بلا». سایت تخصصی امام حسین علیه السلام (in Persian). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ «ركضة طويريج .. من أكبر الفعاليات الدينية في العالم.. تعرف على تأريخها». almasalah.com. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ a b Nakash, Yitzhak (1 January 1993). «An Attempt To Trace the Origin of the Rituals of Āshurā¸». Die Welt des Islams. 33 (2): 161–81. doi:10.1163/157006093X00063. – via Brill (subscription required)

- ^ David Pinault, «Shia Lamentation Rituals and Reinterpretations of the Doctrine of Intercession: Two Cases from Modern India,» History of Religions 38 no. 3 (1999): 285–305.

- ^ Nasr, Vali, «The Shia Revival», Norton, 2006, p. 50

- ^ Puchowski, Douglas (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415994040.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter (ed.) (1979) Taʻziyeh, ritual and drama in Iran New York University Press, New York, ISBN 0814713750

- ^ Ali, Alim (14 February 2009). «Hosay Festival, Westmoreland, Jamaica».

- ^ http://old.jamaica-gleaner.com/pages/history/story0057.htm title= Out Of Many Cultures The People Who Came The Arrival Of The Indians

- ^ Rezaian, Jason. «Iranians relish free food during month of mourning». washingtonpost.

- ^ «Scars on the backs of the young». New Statesman. UK. 6 June 2005. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ «Ashoura day: Why Muslims fast and mourn on Muharram 10». Al Jazeera. 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Ashura observed with blood streams to mark Karbala tragedy». Jafariya News Network. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ «Observing Salat Behind a Shiite Imam». Fiqh. 22 May 2022. Archived from the original on 11 December 2006.

- ^ a b Calmard, J. «‘Azaúdaúrè». Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010). Religions of the World [6 volumes]: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. p. 211. ISBN 978-1598842036.

- ^ Anthony, Michael (2001). Historical Dictionary of Trinidad and Tobago. Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, MD and London. ISBN 978-0810831735.

- ^ Hassner, Ron E. (2016). Religion on the Battlefield. Cornell University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0801451072.

Violence during Ashura.

- ^ B. Metcalf, Islamic revival in British India: Deoband, 1860–1900, p. 58, Princeton University Press (1982).

- ^ J. N. Hollister, The Shi’a of India, p. 178, Luzac and Co, London, (1953).

- ^ Raman, B. (7 January 2002). «Sipah-E-Sahaba Pakistan, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Bin Laden & Ramzi Yousef». Archived from the original on 29 April 2009.

- ^ «Blasts at Shia Ceremonies in Iraq Kill More Than 140». The New York Times. 2 March 2004. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ «Iraqi Shia pilgrims mark holy day». bbc.co.uk. 19 January 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ «Reuters News clip». Youtube.com. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ «Malaysian Wahhabi Extremists Attacked Shia Mourners, Detain 200 + PIC». abna.ir. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ «Deadly bomb attacks on Shia pilgrims in Iraq». bbc.co.uk. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Harooni, Mirwais (6 December 2011). «Blasts across Afghanistan target Shia, 59 dead». Reuters. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ «Dhaka blasts: One dead in attack on Shia Ashura ritual». BBC News. 24 October 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ «Holidays in Iran in 2017».

- ^ a b c «Ashura – Calendar Date». www.calendardate.com. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

Sources[edit]

- Litvak, Meir (1998). Shi’i Scholars of Nineteenth-Century Iraq: The Ulama of Najaf and Karbala. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89296-1

- al Musawi, Muhsin (2006). Reading Iraq: Culture and Power and Conflict. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-070-6

- al Mufid, al-Shaykh Muhammad (December 1982 (1st ed.)). Kitab Al-Irshad. Tahrike Tarsile Quran. ISBN 0-940368-12-9, 978-0-940368-12-5

- al-Azdi, abu Mikhnaf, Maqtal al-Husayn. Shia Ithnasheri Community of Middlesex (PDF)

Further reading[edit]

- Sivan, Emmanuel (1989). «Sunni Radicalism in the Middle East and the Iranian Revolution». International Journal of Middle East Studies. 21 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1017/S0020743800032086. JSTOR 163637. S2CID 162459682.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashura.

- Gordon B. Coutts (Scottish/American, 1868–1937) A Large Oil on Canvas Depicting «The Ashura Rituals, Tangier» (Arabic: عاشوراء ʻĀshūrā’ – Urdu: عاشورا – Persian: عاشورا – Turkish: Aşure Günü). Signed and inscribed: ‘Gordon Coutts/TANGIER (lower right). c. 1920

- Is Aashura a day of mourning or rejoicing?

- Ashura – The Historical Significance and Rewards on Islam Freedom

- Events on the day of Ashura

- «Ashura» An article in Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- What is Ashura? (BBC News)

- What Is Ashura? – by Abdul-Ilah As-Saadi on Al Jazeera

- Ashura Australia – Official website of the Annual Ashura Procession in Sydney

Ашура — это самый важный праздник в календаре мусульман шиитов. Он отмечается в 10-й день месяца Мухаррам — первого месяца в мусульманском календаре. Для шиитов, которые составляют около 15 процентов всех мусульман в мире, это самый большой праздник в году. Однако для остального мира он чаще всего ассоциируется с кровавыми шествиями, во время которых его участники бичуют себя, нанося удары цепями с острыми лезвиями на конце, кинжалами и саблями. Кровавая традиция праздника Ашура в объективе фотографов.

16 ФОТО

Праздник Ашура — это день поминовения внука пророка Мухаммеда, который погиб в 680 году во время битвы при Кербеле (в центральной части Ирака) с войсками халифа Язида из династии Омейядов. Внук пророка Мухаммеда — Хусейн ибн Али — почитается шиитами как третий имам и их духовный предок. Шииты живут в основном в Ираке, Иране и Бахрейне, и являются меньшинством в таких странах как Афганистан, Пакистан, Ливан и Саудовская Аравия.

Для мусульман праздник Ашура — это день траура. Они оплакивают мученическую героическую смерть Хусейна во имя добра и справедливости. И хотя это праздник шиитов, в нем также принимают участие татарские сунниты.

В этот день проходят традиционные шествия мужчин, которые в знак траура по Хусейну калечат свои тела бичами, ножами, мачете и бьют себя в грудь. Так они выражают свою скорбь и солидарность с погибшим внуком пророка Мухаммеда.

Однако не везде праздник Ашура связан с кровавыми обрядами. Известны, например, также обычаи публичного чтения отрывков из произведения XVI века — «Сад мучеников», в котором описываются трагические обстоятельства смерти внука пророка Мухаммеда.

Раны на головах, выпученные глаза и самобичевание: в честь праздника мусульмане истязают себя

6 лет назад · 45107 просмотров

Отмечая один из самых священных дней в своем календаре, шииты избивают друг друга до крови, выкалывают себе глаза и страдают иными способами: миллионы верующих в разных странах мира, включая Индию, Ливан и Грецию, приняли участие в церемониях праздника Ашура. Кровавые празднества не обошли и детей верующих — согласно поверью, с кровью из них выходят грехи.

Источник:

В праздник Ашура отмечается годовщина битвы при Кербеле, во время которой внук пророка Мухаммада, Аль-Хусейн ибн Али аль-Кураши, был убит. Одна из целей церемонии — возродить атмосферу той исторической битвы. Девятый и десятый дни исламского месяца мухаррам — дни траура для шиитов. Чтобы почтить страдания мученика, люди наносят себе травмы, режут и бичуют себя.

Фото, которые вы увидите, демонстрируют ужасающую природу ритуалов Ашура. Например, на этой фотографии мужчина из Аджмера, находящегося в Индии, выкалывает себе глаз, выскочивший из орбиты и сочащийся кровью.

Источник:

Испуганный ребенок, порезанный бритвой, плачет во время ритуала.

Источник:

Источник:

А на этом фото индийские мусульмане стоят в собственной крови.

Особенно шокирующее фото из Ливана вы могли видеть выше — на нем мальчик-подросток обливается кровью, пропитавшей повязку на его голове.

Источник:

Традиционное для Ашура самобичевание в Афинах, Греция.

Источник:

Лица участвующих в ритуале мужчин искажены в экстатическом восторге.

Источник:

Люди с хлыстами не жалеют ни себя, ни окружающих верующих.

Источник:

Их вера сподвигла их рассекать собственную спину клинками.

Пугающая церемония является кульминацией траура, длившегося несколько недель, и практикуется в шиитских общинах по всему миру. Ритуал самобичевания зародился в Южном Ливане и в Ираке. Множество правительственных и религиозных организаций по всему миру осуждают эти практики, так как они крайне опасны для их исполнителей.

Источник:

Источник:

Источник:

Так выглядит чистый исступленный ужас.

Источник:

Сотни людей собрались в Индии, чтобы почтить память павшего в битве имама.

Источник:

На севере Индии праздник выглядит более ярко, красиво и в то же время мирно.

Источник:

Источник:

— переведено специально для fishki.net

Кровавые мистерии Ашура

В ряде мусульманских стран, в которых присутствуют шиитские общины, в частности в Иране, раз в год проводится одна из наиболее впечатляющих культурных достопримечательностей Ирана, кровавый религиозный праздник Ашура, или день памяти имама Хусейна, на всем протяжении которого его последователи в религиозном экстазе самозабвенно предаются самобичеванию. Всюду проводятся массовые шествия – свистят плети, кровь течет ручьем.

Происхождение этого удивительного мероприятия таково. В седьмом веке, в эпоху становления и укрепления ислама, жил-был халиф Язид. Этот халиф не слишком обременял себя религиозными ограничениями – любил шумные кутежи, не чуждался общества женщин и прочих удовольствий. Но, как это часто бывает в истории, светская власть на этой почве вошла в конфликт с властью духовной. В те годы духовным лидером был имам Хусейн, обладавший огромным авторитетом, как бескомпромиссный борец за чистоту канонов Шариата и внук пророка Мухаммеда. В 680 году, спустя десятилетие пребывания Хусейна у кормила духовной власти, отношения между ним и Язидом накалились настолько, что дальнейшее их мирное сосуществование было уже невозможно. В этом году в Мекку на хадж прибыло множество паломников из разных уголков исламской ойкумены. Халиф Язид решил воспользоваться благоприятным моментом, чтобы нанести Хусейну смертельный удар, и с этой целью послал несколько законспирированных наемных убийц.

Однако Хусейн узнал о коварных замыслах Язида. Во время празднования хаджа ему удалось с войском и близкими людьми покинуть Мекку. Через несколько дней в пустынном местечке Кербела Хусейн был окружен многочисленной армией халифа. Обремененные женщинами и детьми, сторонники Хусейна столкнулись с недостатком воды. Спустя неделю, когда жажда стала невыносимой, Хусейн решил встретиться с врагом лицом к лицу. Но прежде ему необходимо было позаботиться о всех неспособных держать в руках оружие. Ночью он потушил в лагере все источники света, чтобы в темноте могли уйти все желающие, лишь самые близкие родственники и лично преданные ему воины были готовы идти с ним в последнее сражение.

Через сутки, на десятый день месяца мухаррам, в день Ашуры, состоялась битва. Многократно преобладающее войско Язида в конце концов сломило сопротивление горстки преданных имаму воинов, истребив их всех. Хусейн пал под стрелами, после чего ему отрубили голову. С тех пор и проводятся траурные церемонии в память об этих печальных событиях. В это время люди поминают имама Хусейна и его героическую гибель, распевают скорбные песни и религиозные гимны, бьют себя кулаками и камнями в грудь.

Наиболее радикальные хлещут себя плетями и цепями по спине, с помощью лезвий и заточенных крючьев наносят порезы на кожу. Впадая в состояние транса, они не чувствуют боли. Подобные действия символизируют их готовность пожертвовать жизнью ради ислама, невзирая на боль и страдания, и тем почтить память имама Хусейна и его жертву. Другие темы, описывающие не менее кровавые и зрелищные массовые мероприятия, находятся здесь: Праздник Урс Аджмер, Фестиваль Тайпусам.

Похожие статьи

Эта статья о священном дне ислама. Для традиционного десерта см. Ашуре. Для использования в других целях см. Ашура (значения).

| Ашура | |

|---|---|

Ашура в память о мученической смерти внука Пророка, Тегеран, 2016 |

|

| Официальное название | عَاشُورَاء ʿĀshūrāʾ (по-арабски) |