Яркое празднество под названием Mardi gras уже много столетий существует во многих странах мира. Веселые парады, красочные карнавальные костюмы,подарки, угощения – все это привлекает тысячи гостей, специально собирающихся на улицах городов, где проводится этот необычный и веселый карнавал. Миллионы туристов заранее покупают туры или отправляются в самостоятельное путешествие по Европе и Америке, чтобы принять участие в этом бесшабашном, ярком и зрелищном событии.

Дата фестиваля

Mardi gras переводится, как «жирный вторник», и всегда начинается за 47 дней до начала католической Пасхи, перед Пепельной средой, а заканчивается в полночь накануне Великого поста. Так как дата Пасхи плавающая, то и фестиваль в соответствии с этим проходит в разные дни, обычно это февраль-март. Длительность праздника – 1-2 недели, плюс подготовительные дни, которые часто занимают больше времени, чем сам карнавал. В 2022 году фестиваль начнется 1 марта.

История праздника

В 17 веке французские колонисты, поселившиеся в Луизиане, организовали первый праздник встречи весны, который спустя много лет перерос в фестиваль мирового значения и покорил множество стран. Первый карнавал датируется 1699 годом, а в 1833 г. он уже получил настоящий размах, когда его организацию спонсировал некий плантатор по имени Бернар Хавьер. С тех пор фестиваль отменяли только в экстренных ситуациях: войны, эпидемии, стихийные бедствия.

Официальная прописка Марди Гра – Новый Орлеан, расположенный в штате Луизиана, США. Именно здесь проходят самые пышные карнавалы, шумные веселые развлечения, яркие шоу. Особенность Орлеанского фестиваля – джазовое сопровождение, музыка эта слышится во время праздника повсюду, ведь этот город – колыбель джаза.

Легенды, связанные с Марди Гра

Их две – одна связана с Россией и именем царственной особы, вторая имеет мифологическую окраску и весьма романтична. Обе версии интересны и имеют своих поклонников, добавляя таинственности и значимости этому роскошному фестивалю.

Первая легенда гласит, что когда-то царевич Алексей Романов, влюбившись в Лидию Тимпсон, роскошную американскую актрису, бросил все и поспешил за ней в Новый Орлеан. Дело было перед самым началом праздника. Узнав о визите царственной особы в город, публика разволновалась, и решила встретить гостя, как подобает, со всеми почестями.

Для него подготовили специальную парадную платформу, на которой красовалась надпись: «Rex» (король), и царевич стал главой праздника. Знатоки утверждают, что именно с этого, 1872 года, были установлены каноны фестиваля, и ежегодно стали выбрать короля с королевой, возглавляющих карнавальные шествия.

По второй легенде, появление этих героев связано с мифической красавицей Роз, и ее любимым Габриэлем. Девушку захватил Люцифер, устроил бал, и если бы она протанцевала с ним до полуночи, ее душа навсегда осталась бы в его лапах. Но парень сумел вызволить любимую до последнее боя курантов, и тем самым спас. С тех пор праздник всегда заканчивается до наступления полуночи.

Где и как проходит Марди Гра

В Новом Орлеане перед началом фестиваля объявляются выходные и перекрываются все главные улицы. Отовсюду звучит джаз, а народ, в предвкушении веселых праздничных событий, приходит в приятное волнение. Начинается праздник первой волной фестиваля – Бахус, который вскрывает все пороки, связанные с алкоголем: пьянство, прелюбодеяние, разврат, карты и прочие осуждаемые христианством грехи. Изначально он задумывался перед началом поста, чтобы оголить эти проблемы и призвать христиан к покаянию. Теперь же он былой смысл утратил и направлен просто на увеселение народа.

Вторая часть – парад Mardi Gras Indians – поистине незабываемое яркое зрелище, сопровождающееся фантастическими костюмами. Главным его атрибутом уже много веков является «Торт трех королей» в форме большого кренделя. Внутри его обычно запекают фигурку пупса, символизирующего младенца Христа. Считается, что кому он попался – весь год будет счастлив.

В Новом Орлеане празднества занимают целых две недели, проходят с большим размахом, с концертами и различными развлекательными мероприятий. Все заканчивается парадом на «Жирный вторник», в котором принимает участие множество народа, в числе их тысячи туристов из разных стран.

Помимо этого, крупные гуляния также проходят в штате Алабама (г. Мобил), который некогда был столицей той самой французской Луизианы, с которой все и началось, и Сан-Диего (Калифорния). В последнем городе праздник отмечается с особым размахом.

Традиции праздника

Как у любого мало-мальски достойного мероприятия, у этого фестиваля также есть свои, давно уже сформировавшиеся интересные традиции. Все участники действа стараются им следовать, как это делали их предки, ведь это не просто праздник, а целый ряд ритуалов и правил, которым приятно и интересно следовать.

- Самое главное – ни в чем не отказывать себе, петь, танцевать, вовсю веселиться от души.

- Бусы – главный атрибут костюма. Причем, чем их больше на участнике карнавала, тем лучше.

- Цвета фестиваля: золотой, фиолетовый, зеленый. Они должны быть выражены в деталях костюма, традиционной выпечке, атрибутах.

- Подарки толпе – во время шествия платформ нужно громко кричать, привлекая внимание участников на платформах, за что они бросают в народ всевозможные украшения, бусы, различные безделушки и сладости.

- Оголение груди – ближе к ночи, когда градус разгула достигает эпогея, в обмен на бусы, которые с платформ бросают в толпу участники, женщины в фееричном экстазе оголяют свои прелести, притом, возраст дамы не имеет значения.

Аналоги в других странах мира

Особенно интересным и необычным является празднование Марди Гра в Германии, где он именуется Фастнахт. Подготовка к событию обычно начинается еще в ноябре-декабре, и привязана она к числу 11 (дата, часы, минуты). Сам фестиваль разворачивает главные события в «Грязный четверг», считающийся женским днем. Все дамы наряжаются в ведьм, выходят на улицы и развлекают народ.

Фаснеткухли

Отличительная черта немецкого аналога праздника – все рядятся в костюмы, состоящие в большинстве случаев из белых покрывал, деревянных масок, и даже дети в школу приходят в карнавальных уборах. Шествия ряженых сопровождаются обильными угощениями в виде сладостей, и традиционного пирога фаснеткухли. Заканчивается все концертом в центре города и фейерверком.

В Польше существует интересный ритуал Podkoziołek, во время которого собирается неженатая молодежь. В средине большой комнаты устанавливается бочка, на ней поднос для денег. Для того, чтобы пригласить на танец понравившуюся девушку, парень бросает на тарелку выкуп. Собранные деньги идут на оплату музыкантам.

В Чехии праздник называется Фашанк. На улицах в этот день полно ряженых в костюмах, символизирующих животных, и персонажей местного фольклора. А во вторник в полночь «хоронят контрабас», рассказывая при этом о его страшных грехах.

Традиционные фестивальные блюда также имеют свои особенности:

- пирог волхвов – во Франции он имеет плоскую форму, изготавливается из слоеного теста, начинка – миндальный крем. В США это пирог в виде рулета, украшенный сверху сахаром традиционных фестивальных цветов;

- каджен – густой суп с мясом и рисом;

- блины – как на русской Масленице. В Дании они пекутся с мясом, в Испании это лепешки-тортильи, в Норвегии их подают с сосисками, во Франции с разнообразными крепами, а в Германии их делают в виде толстого блина-омлета.

Интересные факты

За много веков история фестиваля собрала различные забавные и интересные особенности, которые отличаются в разных странах и регионах. Одно объединяет их всех – безудержное веселье, бесшабашность, костюмированные шествия и традиционные угощения.

- В последнем параде приняло участие 1000 платформ, 600 оркестров и 135 тыс. участников.

- В карнавальный период выпекается и продается более 500 тыс. традиционных тортов, средняя цена которых 40$

- Самый большой торт был выпечен в 2010 г., его смогли отведать 600 человек.

- Самая дорогая платформа на параде достигала в длину 300 футов.

- 2000 парадов прошло в Новом Орлеане с 1857 г.

- Около 500$ тратит участник платформы на «подарки толпе».

- 12,5 тонн бус каждый год разбрасывают для народа во время фестиваля.

Как попасть на фестиваль, цены на билеты

Чтобы принять участие в Марди Гра, нужно изначально заранее купить билеты и забронировать жилье, которое к тому времени процентов на 150 поднимется в цене. Приезжать желательно на неделю раньше начала фестиваля, когда стартуют локальные парады. При этом необходимо изучить места, где захочется побывать. Центр событий – Бурбон-Стрит, самым тихим в плане веселья становится Сент-Чарльз авеню. Стоимость туров колеблется от 770$ (4 дня) до 1500$ (10 дней).

Больше парадов

Многие туристы предпочитают посетить Новый Орлеан в выходные, предшествующие «жирному вторнику», что позволит увидеть наиболее зрелищные мероприятия, в том числе парады Бахус, Энидимон, Рекс и другие.

Кроме того, жилье можно забронировать и в расположенных вблизи городах, где цены буду куда дешевле, чем в эпицентре событий. Что касается билетов, то практически все мероприятия бесплатны. Если захочется получше все увидеть, можно оплатить размещение на трибуне за 10 долларов, или же договориться с хозяевами домов, возле который проходит карнавал, за место на балконе. Также есть возможность оплатить размещение на балконах Бурбон-Стрит (150-200$), или же просто окунуться в гущу событий вместе со всеми, слиться с толпой и почувствовать себя частицей этого роскошного праздника.

Ежегодно в «жирный вторник» тысячи людей съезжаются в Новый Орлеан, чтобы насладиться карнавалом Марди Гра. Языческий праздник, сдобренный христианскими традициями, превратил проводы зимы в фестиваль ярких красок и безудержного кутежа.

Надевайте свои расписные костюмы и маски. Отвратительные мужики расскажут о том, чем Марди Гра похож на нашу Масленицу, а также почему карнавальные гуляния следует закончить до полуночи, чтобы не угодить в лапы Дьявола.

Но сначала врубите новоорлеанский брасс на всю катушку и приготовьтесь пританцовывать:

Языческие традиции

Традиция празднования проводов зимы берет свое начало еще в языческие времена. Практически у всех народов Европы существовали схожие ритуалы, вроде сжигания чучел-тотемов, переодевания в скоморошеские наряды и поедания блинов и других, похожих на солярные символы яств.

В те времена конец холодов — это не просто повод повеселиться на полную катушку перед новым пахотным сезоном. Мороз был вполне реальной угрозой, а зиму можно было запросто и не пережить, поэтому и праздник был вовсе не номинальным.

Христианизация несколько изменила традиции, убрав из них языческие верования, однако логика праздника никуда не ушла. Добавилось то, что после веселых гуляний начинался Великий пост, который готовил христиан к празднованию Пасхи.

Сегодня Европа отмечает конец с зимы с куда большим размахом: Фастнахт в Германии, Курентованье в Словении, Бушояраш в Венгрии и, разумеется, русская Масленица. Со своими отличиями, но везде это раздолье ярмарочной культуры, где ряженые в фольклорных демонов и духов люди предаются потехам по полной программе.

История Марди Гра

Марди Гра переводится с французского, как «жирный вторник». Название праздника говорит само за себя: это и день перед началом католического Великого поста, когда можно в последний раз наесться от пуза, и финальный день Карнавала, которым европейцы издревле провожали зиму.

Марди Гра так сильно вошел в культуру Нового Орлеана, что отменяли его только в самых чрезвычайных случаях, к примеру, во время гражданской войны и вспышки желтой лихорадки в конце XIX века.

Ходит легенда, что традицией появления неформальных «короля» и «королевы» Марди Гра Новый Орлеан обязан великому князю Алексею Александровичу, сыну императора Александра II. Якобы он побывал на одном из фестивалей, где высокому гостю приготовили особую платформу с надписью «Rex» (король), на которой Алексей Александрович должен был проехать на параде.

В 1949 году корону примерил Луи Армстронг, однако чернокожему населению только через десяток лет было позволено участвовать в карнавале вместе со всеми. До того они веселились только в своих районах, а гуляния назывались Зулу. Разумеется, музыка звучала на празднике и до этого, но особый колорит Марди Гра дали именно черные джаз-бенды, добавившие в карнавал улетные ритмы свинга.

Второй справа — Луи Армстронг.

Еще один «король» на вечеринке — это Царь-торт, который традиционно принято подавать к карнавальному столу. В большой бублик-плетенку из датского печенья, обсыпанный фиолетовым и зеленым сахаром, обычно запекают крошечную игрушку в виде ребенка. Тот, кто находит пупса, покупает Царь-торт на следующий год.

Современный Марди Гра

Есть и такая традиция. Прекрасная традиция!

Сегодня главный парад Марди Гра в Новом Орлеане проходит во Французском квартале на улице с говорящим названием Бурбон-Стрит. Местные стараются придерживаться традиций праздника, однако не обошлось и без пикантных новоделов.

С платформ на параде принято разбрасывать безделушки, вроде пластиковых бус и других побрякушек, которые присутствующие зрители должны как-то заслужить. Современные девушки знают как, поэтому на карнавале Марди Гра количество обнаженных на потеху толпы сисек не поддается исчислению. А никто и не против. Сами гуляния продолжаются до утра, а то и того больше. Если за титьки предки могли и не покарать своих излишне веселых потомков, то за продолжение кутежа после «жирного вторника» они бы точно получили по полной программе.

По традиции, пришедшей с христианством, праздник должен был закончиться ровно в полночь. Считалось, что тех, кто продолжает веселиться после этого, заберет с собой Сатана. Байка о том, что князь тьмы увлекает в пляс гуляк, может и не всегда работала, однако позволяла всей общине держаться общего русла и не погружаться в недельный каджунский запой.

Марди Гра, наряду с Хэллоуином и Днем Святого Патрика, давно превратился во всемирный феномен со своими знаковыми атрибутами. Если ты, поджигая чучела и пожевывая блины, вдруг заскучал от того, что наша Масленица не сможет прогнать зиму еще как минимум пару месяцев, смело собирай вещи и отправляйся на кутеж в Новый Орлеан.

Только не перепутай новоорлеанский Марди Гра с Сиднейским Марди Гра Фестивалем, на котором ежегодно проводится один из самых крупных гей-парадов мира. В любом случае не забудь захватить с собой побольше пластиковых бус, вдруг пригодятся.

| Mardi Gras in New Orleans | |

|---|---|

A Mardi Gras Parade in New Orleans, 2011 |

|

| Status | Active |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Location(s) | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Country | United States |

The holiday of Mardi Gras is celebrated in southern Louisiana, including the city of New Orleans. Celebrations are concentrated for about two weeks before and through Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday (the start of lent in the Western Christian tradition). Usually there is one major parade each day (weather permitting); many days have several large parades. The largest and most elaborate parades take place the last five days of the Mardi Gras season. In the final week, many events occur throughout New Orleans and surrounding communities, including parades and balls (some of them masquerade balls).

The parades in New Orleans are organized by social clubs known as krewes; most follow the same parade schedule and route each year. The earliest-established krewes were the Mistick Krewe of Comus, the earliest, Rex, the Knights of Momus and the Krewe of Proteus. Several modern «super krewes» are well known for holding large parades and events (often featuring celebrity guests), such as the Krewe of Endymion, the Krewe of Bacchus, as well as the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club—a predominantly African American krewe. Float riders traditionally toss throws into the crowds. The most common throws are strings of colorful plastic beads, doubloons, decorated plastic «throw cups», and small inexpensive toys. Major krewes follow the same parade schedule and route each year.

While many tourists center their Carnival season activities on Bourbon Street, major parades originate in the Uptown and Mid-City districts and follow a route along St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street, on the upriver side of the French Quarter. Walking parades — most notably the Krewe du Vieux and ‘tit Rex — also take place downtown in the Faubourg Marigny and French Quarter in the weekends preceding Mardi Gras Day. Mardi Gras Day traditionally concludes with the «Meeting of the Courts» between Rex and Comus.[1]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The first record of Mardi Gras being celebrated in Louisiana was at the mouth of the Mississippi River in what is now lower Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, on March 2, 1699. Iberville, Bienville, and their men celebrated it as part of an observance of Catholic practice. The date of the first celebration of the festivities in New Orleans is unknown. A 1730 account by Marc-Antoine Caillot celebrating with music and dance, masking and costuming (including cross-dressing).[2] An account from 1743 that the custom of Carnival balls was already established. Processions and wearing of masks in the streets on Mardi Gras took place. They were sometimes prohibited by law, and were quickly renewed whenever such restrictions were lifted or enforcement waned.

In 1833, Bernard Xavier de Marigny de Mandeville, a rich plantation owner of French descent raised money to fund an official Mardi Gras celebration. James R. Creecy in his book Scenes in the South, and Other Miscellaneous Pieces describes New Orleans Mardi Gras in 1835:[3]

The Carnival at New Orleans, 1885

Shrove Tuesday is a day to be remembered by strangers in New Orleans, for that is the day for fun, frolic, and comic masquerading. All of the mischief of the city is alive and wide awake in active operation. Men and boys, women and girls, bond and free, white and black, yellow and brown, exert themselves to invent and appear in grotesque, quizzical, diabolic, horrible, strange masks, and disguises. Human bodies are seen with heads of beasts and birds, beasts and birds with human heads; demi-beasts, demi-fishes, snakes’ heads and bodies with arms of apes; man-bats from the moon; mermaids; satyrs, beggars, monks, and robbers parade and march on foot, on horseback, in wagons, carts, coaches, cars, &c., in rich confusion, up and down the streets, wildly shouting, singing, laughing, drumming, fiddling, fifeing, and all throwing flour broadcast as they wend their reckless way.

In 1856, 21 businessmen gathered at a club room in the French Quarter to organize a secret society to observe Mardi Gras with a formal parade. They founded New Orleans’ first and oldest krewe, the Mistick Krewe of Comus. According to one historian, «Comus was aggressively English in its celebration of what New Orleans had always considered a French festival. It is hard to think of a clearer assertion than this parade that the lead in the holiday had passed from French-speakers to Anglo-Americans. … To a certain extent, Americans ‘Americanized’ New Orleans and its Creoles. To a certain extent, New Orleans ‘creolized’ the Americans. Thus the wonder of Anglo-Americans boasting of how their business prowess helped them construct a more elaborate version than was traditional. The lead in organized Carnival passed from Creole to American just as political and economic power did over the course of the nineteenth century. The spectacle of Creole-American Carnival, with Americans using Carnival forms to compete with Creoles in the ballrooms and on the streets, represents the creation of a New Orleans culture neither entirely Creole nor entirely American.»[4]

In 1875, Louisiana declared Mardi Gras a legal state holiday.[5] War, economic, political, and weather conditions sometimes led to cancellation of some or all major parades, especially during the American Civil War, World War I and World War II, but the city has always celebrated Carnival.[5]

The 1898, Rex parade, with the theme of «Harvest Queens,» was filmed by the American Mutoscope Co.[6][7] The rumored but long-lost recording was rediscovered in 2022. The two-minute film records 6 parade floats, including one transporting a live ox. In December of 2022, the film was deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant» by the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.[8]

20th and 21st centuries[edit]

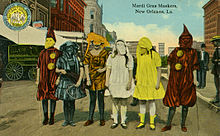

Mardi Gras maskers; c. 1915 postcard

In 1979, the New Orleans police department went on strike. The official parades were canceled or moved to surrounding communities, such as Jefferson Parish, Louisiana. Significantly fewer tourists than usual came to the city. Masking, costuming, and celebrations continued anyway, with National Guard troops maintaining order. Guardsmen prevented crimes against persons or property but made no attempt to enforce laws regulating morality or drug use; for these reasons, some in the French Quarter bohemian community recall 1979 as the city’s best Mardi Gras ever.

In 1991, the New Orleans City Council passed an ordinance that required social organizations, including Mardi Gras Krewes, to certify publicly that they did not discriminate on the basis of race, religion, gender or sexual orientation, to obtain parade permits and other public licenses.[9] Shortly after the law was passed, the city demanded that these krewes provide them with membership lists, contrary to the long-standing traditions of secrecy and the distinctly private nature of these groups. In protest—and because the city claimed the parade gave it jurisdiction to demand otherwise-private membership lists—the 19th-century krewes Comus and Momus stopped parading.[10] Proteus did parade in the 1992 Carnival season but also suspended its parade for a time, returning to the parade schedule in 2000.

Several organizations brought suit against the city, challenging the law as unconstitutional. Two federal courts later declared that the ordinance was an unconstitutional infringement on First Amendment rights of free association, and an unwarranted intrusion on the privacy of the groups subject to the ordinance.[11] The US Supreme Court refused to hear the city’s appeal from this decision.

Today, New Orleans krewes operate under a business structure; membership is open to anyone who pays dues, and any member can have a place on a parade float.

Effects of Hurricane Katrina[edit]

The devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005 caused a few people to question the future of the city’s Mardi Gras celebrations. Mayor Nagin, who was up for reelection in early 2006, tried to play this sentiment for electoral advantage[citation needed]. However, the economics of Carnival were, and are, too important to the city’s revival.

The city government, essentially bankrupt after Hurricane Katrina, pushed for a scaled back celebration to limit strains on city services. However, many krewes insisted that they wanted to and would be ready to parade, so negotiations between krewe leaders and city officials resulted in a compromise schedule. It was scaled back but less severely than originally suggested.

The 2006 New Orleans Carnival schedule included the Krewe du Vieux on its traditional route through Marigny and the French Quarter on February 11, the Saturday two weekends before Mardi Gras. There were several parades on Saturday, February 18, and Sunday the 19th a week before Mardi Gras. Parades followed daily from Thursday night through Mardi Gras. Other than Krewe du Vieux and two Westbank parades going through Algiers, all New Orleans parades were restricted to the Saint Charles Avenue Uptown to Canal Street route, a section of the city which escaped significant flooding. Some krewes unsuccessfully pushed to parade on their traditional Mid-City route, despite the severe flood damage suffered by that neighborhood.

The city restricted how long parades could be on the street and how late at night they could end. National Guard troops assisted with crowd control for the first time since 1979. Louisiana State troopers also assisted, as they have many times in the past. Many floats had been partially submerged in floodwaters for weeks. While some krewes repaired and removed all traces of these effects, others incorporated flood lines and other damage into the designs of the floats.

Most of the locals who worked on the floats and rode on them were significantly affected by the storm’s aftermath. Many had lost most or all of their possessions, but enthusiasm for Carnival was even more intense as an affirmation of life. The themes of many costumes and floats had more barbed satire than usual, with commentary on the trials and tribulations of living in the devastated city. References included MREs, Katrina refrigerators and FEMA trailers, along with much mocking of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and local and national politicians.

By the 2009 season, the Endymion parade had returned to the Mid-City route, and other Krewes expanding their parades Uptown.

2020 tandem float incidents[edit]

In 2020, two parade attendees—one during the Nyx parade, and one during the Endymion parade, were killed after being struck and run over in between interconnected «tandem floats» towed by a single vehicle. Following the incident during the Nyx parade, there were calls for New Orleans officials to address safety issues with these floats (including outright bans, or requiring the gaps to be filled in using a barrier). Following the second death during the Endymion parade on February 22, 2020 (which caused the parade to be halted and cancelled), city officials announced that tandem floats would be banned effective immediately, with vehicles restricted to one, single float only.[12][13][14]

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic[edit]

Unknown to the participants and local leaders at the time, the 2020 Carnival season (with parades running from January through Mardi Gras Day on February 25) coincided with increasing spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States as part of a global epidemic.[15] At the time, the disease was actively being dismissed as a major public health threat by President Donald Trump and his administration.[16] As such, scrutiny over large public gatherings had yet to emerge, while scrutiny over international travel primarily placed an emphasis on restricting travel from China—the country from which the disease originated.[17][15] The first case of COVID-19 in Louisiana was reported on March 9, two weeks after the end of Mardi Gras.[18]

Subsequently, the state of Louisiana saw a significant impact from the pandemic, with New Orleans in particular seeing a high rate of cases. Louisiana State University (LSU) associate professor Susanne Straif-Bourgeoi suggested that the rapid spread may have been aided by Mardi Gras festivities.[19][20] Researchers of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette determined that Louisiana had the fastest growth rate of cases (67.8%, overtaking New York’s 66.1% growth) in the 14 days since its first reported case than any region in the entire world.[21][19]

Mayor LaToya Cantrell stated that she would have cancelled Mardi Gras festivities had she been provided with sufficient warning by the federal government, and criticized the Trump administration for downplaying the threat.[15][22] Amid continued spread of COVID-19 across the country, in early-November 2020 Cantrell stated that celebrations in 2021 would have to be «something different», as Mardi Gras could not be canceled outright since it is a religious observance. A sub-committee of the Mardi Gras Advisory Committee focused on COVID-19 proposed that parades still be held but with strict safety protocols and recommendations, including enforcement of social distancing, highly recommending the wearing of face masks by attendees, discouraging «high value» throws in order to discourage crowding, as well as discouraging the consumption of alcohol, and encouraging more media coverage of parades to allow at-home viewing.[23]

As parades and large gatherings were canceled for the 2021 Mardi Gras season in New Orleans, some locals spent extra effort to decorate their homes and front yards for the holiday. Some nicknamed this «Yardi Gras».[24]

On November 17, 2020, Mayor Cantrell’s communications director Beau Tidwell announced that the city would prohibit parades during Carnival season in 2021. Tidwell once again stressed that Mardi Gras was not «cancelled», but that it would have to be conducted safely, and that allowing parades was not «responsible» as they can be superspreading events.[25][26] This marked the first large-scale cancellation of Mardi Gras parades since the 1979 police strike.[27][28] Other krewes subsequently announced that they would cancel their in-person balls, including Endymion and Rex (who therefore did not name a King and Queen of Mardi Gras for the first time since World War II).[29][27][28]

On February 5, 2021, in response to continued concerns surrounding «recent large crowds in the Quarter» and variants of SARS-CoV-2 as Shrove Tuesday neared, Mayor Cantrell ordered all bars in New Orleans (including those with temporary permits to operate as restaurants) to close from February 12 through February 16 (Mardi Gras), and prohibited to-go drink sales by restaurants, and all packaged liquor sales in the French Quarter. To discourage gatherings, pedestrian access to Bourbon Street, Decatur Street, Frenchmen Street between 7:00 p.m. and 3:00 a.m., and Claiborne Avenue under the bridge, was restricted by checkpoints to those accessing businesses and homes within the areas. Mayor Cantrell stated that she would «rather be accused of doing too much than doing too little.» The move caught some establishments off-guard, as they had been preparing for and anticipating business on Mardi Gras.[30][31]

Parades were allowed to return for 2022.[32] In December 2021, the city announced that parades would have modified routes in 2022 due to New Orleans Police Department staffing shortages.[33][34] On January 6, 2022, Mayor Cantrell stated during a kickoff event that «without a doubt, we will have Mardi Gras in 2022», citing high COVID-19 vaccination rates, and customarily asked residents to «do everything that we know is necessary to keep our people safe.» The Krewe de Jeanne D’Arc ceremonially led their parade with a group of marchers in plague doctor outfits and brooms, tasked to «sweep the plague away».[32]

The city announced COVID-19 protocols for Mardi Gras 2022 in February 2022, which requires, at a minimum, all participants in a parade (including marchers, performers, and those a riding a float) to present proof of vaccination or a negative COVID-19 test from within the past 72 hours. Some krewes chose to not accept negative tests at all, while some krewes (such as the Krewe of Muses, which also announced plans to have COVID-19 rapid tests as throws)[35] had already announced vaccination requirements for parade participants ahead of the official requirement. Despite the presence of Omicron variant, city health director Jennifer Avegno stated that she was confident Mardi Gras could be conducted in a more normal fashion over 2021.[36][37][38]

Traditional colors[edit]

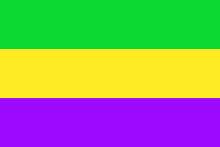

A flag in the traditional colors, as specified in the Rex organization’s original edict and in compliance with the rule of tincture.

The colors traditionally associated with Mardi Gras in New Orleans are purple, green, and gold. The colors were first specified in proclamations by the Rex organization during the lead-up to their inaugural parade in 1872, suggesting that balconies be draped in banners of these colors. It is unknown why these specific colors were chosen; some accounts suggest that they were initially selected solely on their aesthetic appeal, as opposed to any true symbolism.[39][40]

Errol Laborde, author of Marched the Day God: A History of the Rex Organization, presented a theory that the colors were based on heraldry: all three colors correspond to a heraldic tincture, and Rex’s goal may have been to create a tricolor to represent their «kingdom». Purple was widely associated with royalty, while white was already heavily used on other national flags, and was thus avoided. Furthermore, he noted that a flag in green, gold and purple in that order complies with the rule of tincture, which states that metals (gold or silver) can only be placed on or next to other colors, and that colors cannot be placed on or next to other colors.[39]

Following a color-themed Rex parade in 1892 that featured purple, green, and gold-colored floats themed around the concepts, the Rex organization retroactively declared that the three colors in that order symbolized justice, power, and faith. The traditional colors are commonly addressed as purple, green, and gold, in that order—even though this order technically violates the rule of tincture.[39][41]

Contemporary Mardi Gras[edit]

Epiphany[edit]

Epiphany on January 6, has been recognized as the start of the New Orleans Carnival season since at least 1900; locally, it is sometimes known as Twelfth Night although this term properly refers to Epiphany Eve, January 5, the evening of the twelfth day of Christmastide.[42] The Twelfth Night Revelers, New Orleans’ second-oldest Krewe, have staged a parade and masked ball on this date since 1870.[43] A number of other groups such as the Phunny Phorty Phellows, La Société Pas Si Secrète Des Champs-Élysées and the Krewe de Jeanne D’Arc have more recently begun to stage events on Epiphany as well.[44]

Many of Carnival’s oldest societies, such as the Independent Strikers’ Society, hold masked balls but no longer parade in public.[citation needed]

Mardi Gras season continues through Shrove Tuesday or Fat Tuesday.

Days leading up to Mardi Gras Day[edit]

A 2020 study estimated that Mardi Gras brings 1.4 million visitors to New Orleans.[45]

Wednesday night begins with Druids, and is followed by the Mystic Krewe of Nyx, the newest all-female Krewe. Nyx is famous for their highly decorated purses, and has reached Super Krewe status since their founding in 2011.

Thursday night starts off with another all-women’s parade featuring the Krewe of Muses. The parade is relatively new, but its membership has tripled since its start in 2001. It is popular for its throws (highly sought-after decorated shoes and other trinkets) and themes poking fun at politicians and celebrities.

Friday night is the occasion of the large Krewe of Hermes and satirical Krewe D’État parades, ending with one of the fastest-growing krewes, the Krewe of Morpheus.[46] There are several smaller neighborhood parades like the Krewe of Barkus and the Krewe of OAK.

Several daytime parades roll on Saturday (including Krewe of Tucks and Krewe of Isis) and on Sunday (Thoth, Okeanos, and Krewe of Mid-City).

The first of the «super krewes,» Endymion, parades on Saturday night, with the celebrity-led Bacchus parade on Sunday night.

Mardi Gras Day[edit]

The celebrations begin early on Mardi Gras Day, which can fall on any Tuesday between February 3 and March 9 (depending on the date of Easter, and thus of Ash Wednesday).[47]

In New Orleans, the Zulu parade rolls first, starting at 8 am on the corner of Jackson and Claiborne and ending at Broad and Orleans, Rex follows Zulu as it turns onto St. Charles following the traditional Uptown route from Napoleon to St. Charles and then to Canal St. Truck parades follow Rex and often have hundreds of floats blowing loud horns, with entire families riding and throwing much more than just the traditional beads and doubloons. Numerous smaller parades and walking clubs also parade around the city. The Jefferson City Buzzards, the Lyons Club, the Irish Channel Corner Club, Pete Fountain’s Half Fast Walking Club and the KOE all start early in the day Uptown and make their way to the French Quarter with at least one jazz band. At the other end of the old city, the Society of Saint Anne journeys from the Bywater through Marigny and the French Quarter to meet Rex on Canal Street. The Pair-O-Dice Tumblers rambles from bar to bar in Marigny and the French Quarter from noon to dusk. Various groups of Mardi Gras Indians, divided into uptown and downtown tribes, parade in their finery.

For upcoming Mardi Gras Dates through the year 2100 see Mardi Gras Dates.

-

-

Revelers on St. Charles Avenue, 2007

Costumes and masks[edit]

In New Orleans, costumes and masks are seldom publicly worn by non-Krewe members on the days before Fat Tuesday (other than at parties), but are frequently worn on Mardi Gras. Laws against concealing one’s identity with a mask are suspended for the day. Banks are closed, and some businesses and other places with security concerns (such as convenience stores) post signs asking people to remove their masks before entering.

Throws[edit]

A ‘throw’ is the collective term used for the objects that are thrown from floats to parade-goers. Until the 1960s, the most common form was multi-colored strings of glass beads made in Czechoslovakia.

Glass beads were supplanted by less expensive and more durable plastic beads, first from Hong Kong, then from Taiwan, and more recently from China. Lower-cost beads and toys allow float-riders to purchase greater quantities, and throws have become more numerous and common.

In the 1990s, many people lost interest in small, cheap beads, often leaving them where they landed on the ground. Larger, more elaborate metallic beads and strands with figures of animals, people, or other objects have become the sought-after throws. David Redmond’s 2005 film of cultural and economic globalization, Mardi Gras: Made in China, follows the production and distribution of beads from a small factory in Fuzhou, China to the streets of New Orleans during Carnival.[48] The publication of Redmon’s book, Beads, Bodies, and Trash: Public Sex, Global Labor, and the Disposability of Mardi Gras, follows up on the documentary by providing an ethnographic analysis of the social harms, the pleasures, and the consequences of the toxicity that Mardi Gras beads produce.[49]

In addition to the toxicity of tons of plastic, eye injuries from Mardi Gras parade throws are commonplace, and more severe injuries—such as a fractured skull in an infant struck by a coconut—have also been known to occur.[50]

Other Mardi Gras traditions[edit]

[edit]

New Orleans Social clubs play a very large part in the Mardi Gras celebration as hosts of many of the parades on or around Mardi Gras. The two main Mardi Gras parades, Zulu and Rex, are both social club parades. Zulu is a mostly African-American club and Rex is mostly Caucasian. Social clubs host Mardi Gras balls, starting in late January. At these social balls, the queen of the parade (usually a young woman between the ages of 18 and 21, not married and in high school or college) and the king (an older male member of the club) present themselves and their court of maids (young women aged 16 to 21), and different divisions of younger children with small roles in the ball and parade, such as a theme-beformal neighborhood Carnival club ball at local bar room.

After their exclusion from Rex, in 1909 Black Creole and other African American New Orleanians, led by a mutual aid group known as «The Tramps», adorned William Storey with a tin can crown and banana stalk scepter and named him King Zulu.[9][51] This display was meant as a mockery of Rex’s overstated pageantry but in time, Zulu became a grand parade in its own right. By 1949, as an indication of Zulu’s increase in prestige, the krewe named New Orleans’ native son Louis Armstrong as its king.[5]

Being a member of the court requires much preparation, usually months ahead. Women and girls must have dress fittings as early as the May before the parade, as the season of social balls allows little time between each parade. These balls are generally by invitation only. Balls are held at a variety of venues in the city, large and small, depending on the size and budget of the organization. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the French Opera House was a leading venue for New Orleans balls. From the mid 20th century until Hurricane Katrina the Municipal Auditorim was the city’s most famous site for Carnival balls. In more recent years, most are at the ballrooms of various hotels throughout the city. The largest «Super Krewes» use larger venues; Bacchus the Morial Convention Center and Endymion the Superdome.

Doubloons[edit]

Carriers with lit flambeaux on Napoleon Avenue, just before the start of a parade, 2007

One of the many Mardi Gras throws which krewes fling into the crowds, doubloons are large coins, either wood or metal, made in Mardi Gras colors. Artist H. Alvin Sharpe created the modern doubloon for The School of Design (the actual name of the Rex organization). According to the krewe history, in January 1959 Sharpe arrived at the offices of the captain of the krewe with a handful of aluminum discs. Upon entering the office, he threw the doubloons into the captain’s face to prove that they would be safe to throw from the floats. Standard krewe doubloons usually portray the Krewe’s emblem, name, and founding date on one side, and the theme and year of the parade and ball on the other side. Royalty and members of the court may throw specialty doubloons, such as the special Riding Lieutenant doubloons given out by men on horseback in the Rex parade. In the last decade, krewes have minted doubloons specific to each float. Krewes also mint special doubloons of cloisonné or pure silver for its members. They never throw these from the floats. Original Rex doubloons are valuable, but it is nearly impossible for aficionados to find a certified original doubloon. The School of Design did not begin dating their doubloons until a few years after their introduction.

Flambeau carriers[edit]

The flambeau (pronounced «flahm-bo», meaning flame-torch) carrier originally, before electric lighting, served as a beacon for New Orleans parade goers to better enjoy the spectacle of night parades. The first flambeau carriers were slaves. Today, the flambeaux are a connection to the New Orleans version of Carnival and a valued contribution. Many people view flambeau-carrying as a kind of performance art – a valid assessment given the wild gyrations and flourishes displayed by experienced flambeau carriers in a parade. Many individuals are descended from a long line of carriers. Parades that commonly feature flambeaux include Babylon, Bacchus, Chaos, Le Krewe d’Etat, Druids, Endymion, Hermes, Krewe of Muses, Krewe of Orpheus, Krewe of Proteus, Saturn, and Sparta. Flambeaux are powered by naphtha[citation needed], a highly flammable aromatic. It is a tradition, when the flambeau carriers pass by during a parade, to toss quarters to them in thanks for carrying the lights of Carnival. In the 21st century, though, handing dollar bills is common.

Rex[edit]

Each year in New Orleans, krewes are responsible for electing Rex, the king of the carnival.[52] The Rex Organization was formed to create a daytime parade for the residents of the city. The Rex motto is, «Pro Bono Publico—for the public good.»[53]

-

Arrival of Rex, monarch of Mardi Gras, as seen on an early 20th-century postcard

-

Rex, presented with freedom of the city; early 20th century postcard

-

Rex in procession down Canal Street; postcard from c. 1900

-

The Rex pageant, Mardi Gras Day, New Orleans, La., c. 1907

New Orleans Zulu or Mardi Gras Coconut[edit]

Revelers on Basin Street examine their parade catches, including a Zulu Coconut, 2009

One of the most famous and the most sought after throws, is the Zulu Coconut also known as the Golden Nugget and the Mardi Gras Coconut.[10] The coconut is mentioned as far back as 1910, where they were given in a natural «hairy» state. The coconut was thrown as a cheap alternative, especially in 1910 when the bead throws were made of glass. Before the Krewe of Zulu threw coconuts, they threw walnuts that were painted gold. This is where the name «Golden Nugget» originally came from. It is thought that Zulu switched from walnuts to coconuts in the early 1920s when a local painter, Lloyd Lucus, started to paint coconuts. Most of the coconuts have two decorations. The first is painted gold with added glitter, and the second is painted like the famous black Zulu faces. In 1988, the city forbade Zulu from throwing coconuts due to the risk of injury; they are now handed to onlookers rather than thrown. In the year 2000, a local electronics engineer, Willie Clark, introduced an upgraded version of the classic, naming them Mardi Gras Coconuts. These new coconuts were first used by the club in 2002, giving the souvenirs to royalty and city notables.

Ojen liqueur[edit]

Aguardiente de Ojén (es), or simply «ojen» («OH-hen») as it is known in English, is a Spanish anisette traditionally consumed during the New Orleans Mardi Gras festivities.[54] In Ojén, the original Spanish town where it is produced, production stopped for years, but it started again in early 2014 by means of the distillery company Dominique Mertens Impex. S.L.[55]

House floats[edit]

In 2021 due to the cancellation of parades due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the practice of decorating homes in the style of parade floats emerged as an alternative, dubbed «home floats» or «house floats». The concept was popularized immediately after the announcement that in-person parades would be prohibited, stemming from a post on Twitter by Megan Boudreaux. She later established a formal «Krewe of House Floats», with participants being listed in an interactive map on its website so local residents can tour them.[56] The revised celebration was nicknamed «Yardi Gras» by residents.[24] Even the dog parade, held by the Mystic Krewe of Mardi Paws in Covington, opted to make «dog house floats’ in 2021.[57][58]

Public nudity[edit]

A topless woman at a French Quarter coffee house, Mardi Gras afternoon, 2009

Wearing less clothing than considered decent in other contexts during Mardi Gras has been documented since 1889, when the Times-Democrat decried the «degree of immodesty exhibited by nearly all female masqueraders seen on the streets.» Risqué costumes, including body painting, are fairly common. The practice of exposing female breasts in exchange for Mardi Gras beads, however, was mostly limited to tourists in the upper Bourbon Street area.[5][59] In the crowded streets of the French Quarter, generally avoided by locals on Mardi Gras Day, flashers on balconies cause crowds to form on the streets.

In the last decades of the 20th century, the rise in producing commercial videotapes catering to voyeurs helped encourage a tradition of women baring their breasts in exchange for beads and trinkets. Social scientists studying «ritual disrobement» found, at Mardi Gras 1991, 1,200 instances of body-baring in exchange for beads or other favors.[59]

Additional photographs[edit]

- Faubourg Marigny Mardi Gras costumes

- French Quarter Mardi Gras costumes

See also[edit]

- Mardi Gras Mambo

- French Quarter Festival

References[edit]

- ^ «Comus brings Carnival to glittering conclusion | The New Orleans Advocate — New Orleans, Louisiana». www.theneworleansadvocate.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20150121193427/http://acompanymanbook.com/infobox/excerpt/ Excerpt | A Company Man — The Book

- ^ Creecy, James R. (1860). Scenes in the South, and Other Miscellaneous Pieces. Washington: T. McGill. pp. 43, 44. OCLC 3302746.

Scenes in the South, and Other Miscellaneous Pieces.

- ^ All on a Mardi Gras Day: Episodes in the History of New Orleans Carnival by Reid Mitchell. Harvard University Press:1995. ISBN 0-674-01622-X pg 25, 26

- ^ a b c d Sparks, R. American Sodom: New Orleans Faces Its Critics and an Uncertain Future. La Louisiane à la dérive. The École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Coloquio — December 16, 2005.

- ^ Pope, John (June 19, 2022). «Long-lost film of 1898 Rex parade is believed to be the oldest footage shot in New Orleans». NOLA.com. New Orleans. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ Traub, Alex (June 23, 2022). «After Decades of Searching, 1898 Film of New Orleans Mardi Gras Is Found». New York Times. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ Ulaby, Neda (December 14, 2022). «‘Iron Man,’ ‘Super Fly’ and ‘Carrie’ are inducted into the National Film Registry». NPR. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Three centuries of Mardi Gras history. From: carnaval.com. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ a b Deja Krewe. The Times-Picayune. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ The decision of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals appears at volume 42, page 1483 of the Federal Reporter (3rd Series), or 42 F.3d 1483 (5th Cir. 1995).

- ^ «Tandem float ban: ‘It’s a real problem’ says Carnival historian Laborde». WWLTV.com. Tegna Inc. February 23, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Masson, Rob. «Calls for new tandem float restrictions after Nyx death». Fox8Live.com. Gray Television. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ «Tandem floats eliminated from remaining parades after Endymion accident, officials say». NOLA.com. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c «‘We were not given a warning’: New Orleans mayor says federal inaction informed Mardi Gras decision ahead of covid-19 outbreak». Washington Post. March 26, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Blake, Aaron (March 17, 2020). «A timeline of Trump playing down the coronavirus threat». The Washington Post. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ Mason, Jeff; Holland, Steve (March 9, 2020). «Trump’s focus on coronavirus numbers could backfire, health experts say». Reuters. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ «COVID-19 Timeline: See how fast things have changed in Louisiana». WWL. March 22, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ a b «New Orleans has some of the highest coronavirus infection rates in the U.S. — yet it’s overlooked». NOLA.com. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Finch, Chris. «Gov. Edwards: Mardi Gras caused many cases of coronavirus in New Orleans area». Fox8Live.com. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Daigle, Adam. «Coronavirus cases grew faster in Louisiana than anywhere else in the world: UL study». The Advocate. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ «New Orleans would have canceled Mardi Gras if feds had taken coronavirus more seriously, Mayor says». WWL. Tegna, Inc. March 26, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ «Mardi Gras not cancelled but will be ‘different’ in 2021, city says». wwltv.com. November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Taylor, Alan. «Photos: Preparing for «Yardi Gras» in New Orleans — The Atlantic». The Atlantic. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Asmelash, Leah (November 17, 2020). «Due to Covid-19, Mardi Gras parades are canceled in New Orleans next year». CNN. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Del Rosario, Alexandra (November 18, 2020). «New Orleans Cancels Mardi Gras Parades For 2021 Due To Coronavirus». Deadline. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ a b «Endymion announces cancellation of all 2021 Carnival events». wwltv.com. November 19, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ a b «Rex cancels 2021 Mardi Gras ball in wake of parade ban, won’t crown king and queen». NOLA.com. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Mumphrey, Nicole. «Krewe of Bacchus announces virtual 2021 Mardi Gras plans». Fox8Live.com. Gray Television. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Burnside, Tina; Hunter, Marnie. «New Orleans closing bars and banning to-go drinks during Mardi Gras». cnn.com. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Adelson, Jeff; Williams, Jessica (February 5, 2021). «All New Orleans bars closed for Mardi Gras, access restricted to major streets under new rules». NOLA.com. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b writer, DOUG MACCASH | Staff. «Mayor LaToya Cantrell won’t bow down: ‘Without a doubt, we will have Mardi Gras in 2022’«. NOLA.com. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ writer, DOUG MACCASH | Staff. «Zulu and Endymion altered, all parades trimmed: Cantrell reveals 2022 Mardi Gras routes». NOLA.com. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ writer, DOUG MACCASH | Staff. «Thoth Mardi Gras parade pleads for City Hall to restore traditional route, but the answer is no». NOLA.com. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Team, WDSU Digital (February 24, 2022). «Where you can get a COVID-19 test before Mardi Gras weekend». WDSU. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ MacCash, Doug. «For New Orleans’ Mardi Gras season parades, riders must have vaccines or negative test». NOLA.com. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Spera, Keith. «Mardi Gras season krewes, bands figure out how to roll with New Orleans’ COVID rules». NOLA.com. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ MacCash, Doug. «Krewe of Muses tells riders they must be fully vaccinated — no exceptions». NOLA.com. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c «The Truth About Carnival’s Colors». My New Orleans. February 13, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ Laborde, Errol (2007). Krewe: The Early New Orleans Carnival: Comus to Zulu. Metairie, La.: Carnival Press. pp. 57–61. ISBN 978-0-9792273-0-1.

- ^ Laborde, Peggy Scott (June 24, 2015). New Orleans Mardi Gras Moments. Pelican Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 9781455621200.

- ^ Rightor, Henry (1900). Standard history of New Orleans, Louisiana, giving a description of the natural advantages, natural history … settlement, Indians, Creoles, municipal and military history, mercantile and commercial interests, banking, transportation, struggles against high water, the press, educational … etc. Harvard University. Chicago, The Lewis Publishing Company.

- ^ Strachan, Sue (January 8, 2016). «Twelfth Night Revelers kicks off 2016 Carnival at ball». The Times-Picayune. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Stromquist, Kat (January 3, 2018). «12 parties to go to on Twelfth Night in New Orleans». Gambit. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Chavez, Roby (February 16, 2022). «For New Orleans, the return of Mardi Gras is critical ‘for our pocketbooks and our souls’«. PBS NewsHour. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ «Krewe of Morpheus». www.kreweofmorpheus.com.

- ^ «Mardi Gras Dates — Mardi Gras New Orleans». www.mardigrasneworleans.com.

- ^ David Redmon (2008). Mardi Gras: Made in China. Culture Unplugged. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ Redmon, David (July 8, 2014). Beads, Bodies, and Trash: Public Sex, Global Labor, and the Disposability of Mardi Gras. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-52540-4.

- ^ Copeland, CS (January–February 2014). «It’s Not All Bon Temps: Mardi Gras Can Prove Hazardous» (PDF). Healthcare Journal of New Orleans: 26–30.

- ^ Mardi Gras History. From: mardigrasneworleans.com. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ «Krewe». American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ^ «Rex King of Carnival». Rex Organization. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ^ «New Orleans Nostalgia, «Banana Republics and Ojen Cocktails», Ned Hémard, 2007″ (PDF).

- ^ Dominique Mertens Impex. S.L., Ojén, aguardiente superior, official website, in Spanish

- ^ Juhasz, Aubri (February 8, 2021). «House Floats Keep Spirits And Artists Afloat In What Organizers Hope Is A Locals-Only Mardi Gras». WWNO. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Wolfe, Rachel (January 22, 2021). «How to Celebrate Mardi Gras During Covid: Turn Your House Into a Parade Float». Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ «Mardi Gras 2021 Parade Cancellations Inspire ‘Dog House Floats’ Created to Safely Spread Cheer». PEOPLE.com. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Shrum, W. and J. Kilburn. «Ritual Disrobement at Mardi Gras: Ceremonial Exchange and Moral Order». Social Forces, Vol. 75, No. 2. (Dec. 1996), pp. 423-458.

External links[edit]

- Carnival New Orleans History of Mardi Gras with vintage and modern pictures

- Mardi Gras Unmasked Definitive Mardi Gras and king cake histories

- MardiGras.com Web site affiliated with New Orleans’ Times-Picayune newspaper

- Mardi Gras 2014 celebration photos

| Mardi Gras in New Orleans | |

|---|---|

A Mardi Gras Parade in New Orleans, 2011 |

|

| Status | Active |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Location(s) | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Country | United States |

The holiday of Mardi Gras is celebrated in southern Louisiana, including the city of New Orleans. Celebrations are concentrated for about two weeks before and through Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday (the start of lent in the Western Christian tradition). Usually there is one major parade each day (weather permitting); many days have several large parades. The largest and most elaborate parades take place the last five days of the Mardi Gras season. In the final week, many events occur throughout New Orleans and surrounding communities, including parades and balls (some of them masquerade balls).

The parades in New Orleans are organized by social clubs known as krewes; most follow the same parade schedule and route each year. The earliest-established krewes were the Mistick Krewe of Comus, the earliest, Rex, the Knights of Momus and the Krewe of Proteus. Several modern «super krewes» are well known for holding large parades and events (often featuring celebrity guests), such as the Krewe of Endymion, the Krewe of Bacchus, as well as the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club—a predominantly African American krewe. Float riders traditionally toss throws into the crowds. The most common throws are strings of colorful plastic beads, doubloons, decorated plastic «throw cups», and small inexpensive toys. Major krewes follow the same parade schedule and route each year.

While many tourists center their Carnival season activities on Bourbon Street, major parades originate in the Uptown and Mid-City districts and follow a route along St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street, on the upriver side of the French Quarter. Walking parades — most notably the Krewe du Vieux and ‘tit Rex — also take place downtown in the Faubourg Marigny and French Quarter in the weekends preceding Mardi Gras Day. Mardi Gras Day traditionally concludes with the «Meeting of the Courts» between Rex and Comus.[1]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The first record of Mardi Gras being celebrated in Louisiana was at the mouth of the Mississippi River in what is now lower Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, on March 2, 1699. Iberville, Bienville, and their men celebrated it as part of an observance of Catholic practice. The date of the first celebration of the festivities in New Orleans is unknown. A 1730 account by Marc-Antoine Caillot celebrating with music and dance, masking and costuming (including cross-dressing).[2] An account from 1743 that the custom of Carnival balls was already established. Processions and wearing of masks in the streets on Mardi Gras took place. They were sometimes prohibited by law, and were quickly renewed whenever such restrictions were lifted or enforcement waned.

In 1833, Bernard Xavier de Marigny de Mandeville, a rich plantation owner of French descent raised money to fund an official Mardi Gras celebration. James R. Creecy in his book Scenes in the South, and Other Miscellaneous Pieces describes New Orleans Mardi Gras in 1835:[3]

The Carnival at New Orleans, 1885

Shrove Tuesday is a day to be remembered by strangers in New Orleans, for that is the day for fun, frolic, and comic masquerading. All of the mischief of the city is alive and wide awake in active operation. Men and boys, women and girls, bond and free, white and black, yellow and brown, exert themselves to invent and appear in grotesque, quizzical, diabolic, horrible, strange masks, and disguises. Human bodies are seen with heads of beasts and birds, beasts and birds with human heads; demi-beasts, demi-fishes, snakes’ heads and bodies with arms of apes; man-bats from the moon; mermaids; satyrs, beggars, monks, and robbers parade and march on foot, on horseback, in wagons, carts, coaches, cars, &c., in rich confusion, up and down the streets, wildly shouting, singing, laughing, drumming, fiddling, fifeing, and all throwing flour broadcast as they wend their reckless way.

In 1856, 21 businessmen gathered at a club room in the French Quarter to organize a secret society to observe Mardi Gras with a formal parade. They founded New Orleans’ first and oldest krewe, the Mistick Krewe of Comus. According to one historian, «Comus was aggressively English in its celebration of what New Orleans had always considered a French festival. It is hard to think of a clearer assertion than this parade that the lead in the holiday had passed from French-speakers to Anglo-Americans. … To a certain extent, Americans ‘Americanized’ New Orleans and its Creoles. To a certain extent, New Orleans ‘creolized’ the Americans. Thus the wonder of Anglo-Americans boasting of how their business prowess helped them construct a more elaborate version than was traditional. The lead in organized Carnival passed from Creole to American just as political and economic power did over the course of the nineteenth century. The spectacle of Creole-American Carnival, with Americans using Carnival forms to compete with Creoles in the ballrooms and on the streets, represents the creation of a New Orleans culture neither entirely Creole nor entirely American.»[4]

In 1875, Louisiana declared Mardi Gras a legal state holiday.[5] War, economic, political, and weather conditions sometimes led to cancellation of some or all major parades, especially during the American Civil War, World War I and World War II, but the city has always celebrated Carnival.[5]

The 1898, Rex parade, with the theme of «Harvest Queens,» was filmed by the American Mutoscope Co.[6][7] The rumored but long-lost recording was rediscovered in 2022. The two-minute film records 6 parade floats, including one transporting a live ox. In December of 2022, the film was deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant» by the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.[8]

20th and 21st centuries[edit]

Mardi Gras maskers; c. 1915 postcard

In 1979, the New Orleans police department went on strike. The official parades were canceled or moved to surrounding communities, such as Jefferson Parish, Louisiana. Significantly fewer tourists than usual came to the city. Masking, costuming, and celebrations continued anyway, with National Guard troops maintaining order. Guardsmen prevented crimes against persons or property but made no attempt to enforce laws regulating morality or drug use; for these reasons, some in the French Quarter bohemian community recall 1979 as the city’s best Mardi Gras ever.

In 1991, the New Orleans City Council passed an ordinance that required social organizations, including Mardi Gras Krewes, to certify publicly that they did not discriminate on the basis of race, religion, gender or sexual orientation, to obtain parade permits and other public licenses.[9] Shortly after the law was passed, the city demanded that these krewes provide them with membership lists, contrary to the long-standing traditions of secrecy and the distinctly private nature of these groups. In protest—and because the city claimed the parade gave it jurisdiction to demand otherwise-private membership lists—the 19th-century krewes Comus and Momus stopped parading.[10] Proteus did parade in the 1992 Carnival season but also suspended its parade for a time, returning to the parade schedule in 2000.

Several organizations brought suit against the city, challenging the law as unconstitutional. Two federal courts later declared that the ordinance was an unconstitutional infringement on First Amendment rights of free association, and an unwarranted intrusion on the privacy of the groups subject to the ordinance.[11] The US Supreme Court refused to hear the city’s appeal from this decision.

Today, New Orleans krewes operate under a business structure; membership is open to anyone who pays dues, and any member can have a place on a parade float.

Effects of Hurricane Katrina[edit]

The devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005 caused a few people to question the future of the city’s Mardi Gras celebrations. Mayor Nagin, who was up for reelection in early 2006, tried to play this sentiment for electoral advantage[citation needed]. However, the economics of Carnival were, and are, too important to the city’s revival.

The city government, essentially bankrupt after Hurricane Katrina, pushed for a scaled back celebration to limit strains on city services. However, many krewes insisted that they wanted to and would be ready to parade, so negotiations between krewe leaders and city officials resulted in a compromise schedule. It was scaled back but less severely than originally suggested.

The 2006 New Orleans Carnival schedule included the Krewe du Vieux on its traditional route through Marigny and the French Quarter on February 11, the Saturday two weekends before Mardi Gras. There were several parades on Saturday, February 18, and Sunday the 19th a week before Mardi Gras. Parades followed daily from Thursday night through Mardi Gras. Other than Krewe du Vieux and two Westbank parades going through Algiers, all New Orleans parades were restricted to the Saint Charles Avenue Uptown to Canal Street route, a section of the city which escaped significant flooding. Some krewes unsuccessfully pushed to parade on their traditional Mid-City route, despite the severe flood damage suffered by that neighborhood.

The city restricted how long parades could be on the street and how late at night they could end. National Guard troops assisted with crowd control for the first time since 1979. Louisiana State troopers also assisted, as they have many times in the past. Many floats had been partially submerged in floodwaters for weeks. While some krewes repaired and removed all traces of these effects, others incorporated flood lines and other damage into the designs of the floats.

Most of the locals who worked on the floats and rode on them were significantly affected by the storm’s aftermath. Many had lost most or all of their possessions, but enthusiasm for Carnival was even more intense as an affirmation of life. The themes of many costumes and floats had more barbed satire than usual, with commentary on the trials and tribulations of living in the devastated city. References included MREs, Katrina refrigerators and FEMA trailers, along with much mocking of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and local and national politicians.

By the 2009 season, the Endymion parade had returned to the Mid-City route, and other Krewes expanding their parades Uptown.

2020 tandem float incidents[edit]

In 2020, two parade attendees—one during the Nyx parade, and one during the Endymion parade, were killed after being struck and run over in between interconnected «tandem floats» towed by a single vehicle. Following the incident during the Nyx parade, there were calls for New Orleans officials to address safety issues with these floats (including outright bans, or requiring the gaps to be filled in using a barrier). Following the second death during the Endymion parade on February 22, 2020 (which caused the parade to be halted and cancelled), city officials announced that tandem floats would be banned effective immediately, with vehicles restricted to one, single float only.[12][13][14]

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic[edit]

Unknown to the participants and local leaders at the time, the 2020 Carnival season (with parades running from January through Mardi Gras Day on February 25) coincided with increasing spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States as part of a global epidemic.[15] At the time, the disease was actively being dismissed as a major public health threat by President Donald Trump and his administration.[16] As such, scrutiny over large public gatherings had yet to emerge, while scrutiny over international travel primarily placed an emphasis on restricting travel from China—the country from which the disease originated.[17][15] The first case of COVID-19 in Louisiana was reported on March 9, two weeks after the end of Mardi Gras.[18]

Subsequently, the state of Louisiana saw a significant impact from the pandemic, with New Orleans in particular seeing a high rate of cases. Louisiana State University (LSU) associate professor Susanne Straif-Bourgeoi suggested that the rapid spread may have been aided by Mardi Gras festivities.[19][20] Researchers of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette determined that Louisiana had the fastest growth rate of cases (67.8%, overtaking New York’s 66.1% growth) in the 14 days since its first reported case than any region in the entire world.[21][19]

Mayor LaToya Cantrell stated that she would have cancelled Mardi Gras festivities had she been provided with sufficient warning by the federal government, and criticized the Trump administration for downplaying the threat.[15][22] Amid continued spread of COVID-19 across the country, in early-November 2020 Cantrell stated that celebrations in 2021 would have to be «something different», as Mardi Gras could not be canceled outright since it is a religious observance. A sub-committee of the Mardi Gras Advisory Committee focused on COVID-19 proposed that parades still be held but with strict safety protocols and recommendations, including enforcement of social distancing, highly recommending the wearing of face masks by attendees, discouraging «high value» throws in order to discourage crowding, as well as discouraging the consumption of alcohol, and encouraging more media coverage of parades to allow at-home viewing.[23]

As parades and large gatherings were canceled for the 2021 Mardi Gras season in New Orleans, some locals spent extra effort to decorate their homes and front yards for the holiday. Some nicknamed this «Yardi Gras».[24]

On November 17, 2020, Mayor Cantrell’s communications director Beau Tidwell announced that the city would prohibit parades during Carnival season in 2021. Tidwell once again stressed that Mardi Gras was not «cancelled», but that it would have to be conducted safely, and that allowing parades was not «responsible» as they can be superspreading events.[25][26] This marked the first large-scale cancellation of Mardi Gras parades since the 1979 police strike.[27][28] Other krewes subsequently announced that they would cancel their in-person balls, including Endymion and Rex (who therefore did not name a King and Queen of Mardi Gras for the first time since World War II).[29][27][28]

On February 5, 2021, in response to continued concerns surrounding «recent large crowds in the Quarter» and variants of SARS-CoV-2 as Shrove Tuesday neared, Mayor Cantrell ordered all bars in New Orleans (including those with temporary permits to operate as restaurants) to close from February 12 through February 16 (Mardi Gras), and prohibited to-go drink sales by restaurants, and all packaged liquor sales in the French Quarter. To discourage gatherings, pedestrian access to Bourbon Street, Decatur Street, Frenchmen Street between 7:00 p.m. and 3:00 a.m., and Claiborne Avenue under the bridge, was restricted by checkpoints to those accessing businesses and homes within the areas. Mayor Cantrell stated that she would «rather be accused of doing too much than doing too little.» The move caught some establishments off-guard, as they had been preparing for and anticipating business on Mardi Gras.[30][31]

Parades were allowed to return for 2022.[32] In December 2021, the city announced that parades would have modified routes in 2022 due to New Orleans Police Department staffing shortages.[33][34] On January 6, 2022, Mayor Cantrell stated during a kickoff event that «without a doubt, we will have Mardi Gras in 2022», citing high COVID-19 vaccination rates, and customarily asked residents to «do everything that we know is necessary to keep our people safe.» The Krewe de Jeanne D’Arc ceremonially led their parade with a group of marchers in plague doctor outfits and brooms, tasked to «sweep the plague away».[32]

The city announced COVID-19 protocols for Mardi Gras 2022 in February 2022, which requires, at a minimum, all participants in a parade (including marchers, performers, and those a riding a float) to present proof of vaccination or a negative COVID-19 test from within the past 72 hours. Some krewes chose to not accept negative tests at all, while some krewes (such as the Krewe of Muses, which also announced plans to have COVID-19 rapid tests as throws)[35] had already announced vaccination requirements for parade participants ahead of the official requirement. Despite the presence of Omicron variant, city health director Jennifer Avegno stated that she was confident Mardi Gras could be conducted in a more normal fashion over 2021.[36][37][38]

Traditional colors[edit]

A flag in the traditional colors, as specified in the Rex organization’s original edict and in compliance with the rule of tincture.

The colors traditionally associated with Mardi Gras in New Orleans are purple, green, and gold. The colors were first specified in proclamations by the Rex organization during the lead-up to their inaugural parade in 1872, suggesting that balconies be draped in banners of these colors. It is unknown why these specific colors were chosen; some accounts suggest that they were initially selected solely on their aesthetic appeal, as opposed to any true symbolism.[39][40]

Errol Laborde, author of Marched the Day God: A History of the Rex Organization, presented a theory that the colors were based on heraldry: all three colors correspond to a heraldic tincture, and Rex’s goal may have been to create a tricolor to represent their «kingdom». Purple was widely associated with royalty, while white was already heavily used on other national flags, and was thus avoided. Furthermore, he noted that a flag in green, gold and purple in that order complies with the rule of tincture, which states that metals (gold or silver) can only be placed on or next to other colors, and that colors cannot be placed on or next to other colors.[39]

Following a color-themed Rex parade in 1892 that featured purple, green, and gold-colored floats themed around the concepts, the Rex organization retroactively declared that the three colors in that order symbolized justice, power, and faith. The traditional colors are commonly addressed as purple, green, and gold, in that order—even though this order technically violates the rule of tincture.[39][41]

Contemporary Mardi Gras[edit]

Epiphany[edit]

Epiphany on January 6, has been recognized as the start of the New Orleans Carnival season since at least 1900; locally, it is sometimes known as Twelfth Night although this term properly refers to Epiphany Eve, January 5, the evening of the twelfth day of Christmastide.[42] The Twelfth Night Revelers, New Orleans’ second-oldest Krewe, have staged a parade and masked ball on this date since 1870.[43] A number of other groups such as the Phunny Phorty Phellows, La Société Pas Si Secrète Des Champs-Élysées and the Krewe de Jeanne D’Arc have more recently begun to stage events on Epiphany as well.[44]

Many of Carnival’s oldest societies, such as the Independent Strikers’ Society, hold masked balls but no longer parade in public.[citation needed]

Mardi Gras season continues through Shrove Tuesday or Fat Tuesday.

Days leading up to Mardi Gras Day[edit]

A 2020 study estimated that Mardi Gras brings 1.4 million visitors to New Orleans.[45]

Wednesday night begins with Druids, and is followed by the Mystic Krewe of Nyx, the newest all-female Krewe. Nyx is famous for their highly decorated purses, and has reached Super Krewe status since their founding in 2011.

Thursday night starts off with another all-women’s parade featuring the Krewe of Muses. The parade is relatively new, but its membership has tripled since its start in 2001. It is popular for its throws (highly sought-after decorated shoes and other trinkets) and themes poking fun at politicians and celebrities.

Friday night is the occasion of the large Krewe of Hermes and satirical Krewe D’État parades, ending with one of the fastest-growing krewes, the Krewe of Morpheus.[46] There are several smaller neighborhood parades like the Krewe of Barkus and the Krewe of OAK.

Several daytime parades roll on Saturday (including Krewe of Tucks and Krewe of Isis) and on Sunday (Thoth, Okeanos, and Krewe of Mid-City).

The first of the «super krewes,» Endymion, parades on Saturday night, with the celebrity-led Bacchus parade on Sunday night.

Mardi Gras Day[edit]

The celebrations begin early on Mardi Gras Day, which can fall on any Tuesday between February 3 and March 9 (depending on the date of Easter, and thus of Ash Wednesday).[47]

In New Orleans, the Zulu parade rolls first, starting at 8 am on the corner of Jackson and Claiborne and ending at Broad and Orleans, Rex follows Zulu as it turns onto St. Charles following the traditional Uptown route from Napoleon to St. Charles and then to Canal St. Truck parades follow Rex and often have hundreds of floats blowing loud horns, with entire families riding and throwing much more than just the traditional beads and doubloons. Numerous smaller parades and walking clubs also parade around the city. The Jefferson City Buzzards, the Lyons Club, the Irish Channel Corner Club, Pete Fountain’s Half Fast Walking Club and the KOE all start early in the day Uptown and make their way to the French Quarter with at least one jazz band. At the other end of the old city, the Society of Saint Anne journeys from the Bywater through Marigny and the French Quarter to meet Rex on Canal Street. The Pair-O-Dice Tumblers rambles from bar to bar in Marigny and the French Quarter from noon to dusk. Various groups of Mardi Gras Indians, divided into uptown and downtown tribes, parade in their finery.

For upcoming Mardi Gras Dates through the year 2100 see Mardi Gras Dates.

-

-

Revelers on St. Charles Avenue, 2007

Costumes and masks[edit]