| Memorial Day | |

|---|---|

The gravestones at Arlington National Cemetery are decorated with U.S. flags during Memorial Day weekend of 2008. |

|

| Official name | Memorial Day |

| Observed by | Americans |

| Type | Federal |

| Observances | U.S. military personnel who died in service |

| Date | Last Monday in May |

| 2022 date | May 30 |

| 2023 date | May 29 |

| 2024 date | May 27 |

| 2025 date | May 26 |

| Frequency | Annual |

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day[1]) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have died while serving in the United States armed forces.[2] It is observed on the last Monday of May. From 1868 to 1970 it was observed on May 30.[3]

Many people visit cemeteries and memorials on Memorial Day to honor and mourn those who died while serving in the U.S. military. Many volunteers place American flags on the graves of military personnel in national cemeteries. Memorial Day is also considered the unofficial beginning of summer in the United States.[4]

The first national observance of Memorial Day occurred on May 30, 1868.[5] Then known as Decoration Day, the holiday was proclaimed by Commander in Chief John A. Logan of the Grand Army of the Republic to honor the Union soldiers who had died in the Civil War.[6] This national observance was preceded by many local ones between the end of the Civil War and Logan’s declaration. Many cities and people have claimed to be the first to observe it. However, in 2022, the National Cemetery Administration, a division of the Department of Veterans Affairs, credited Mary Ann Williams with originating the «idea of strewing the graves of Civil War soldiers — Union and Confederate» with flowers.[7]

Official recognition as a holiday spread among the states, beginning with New York in 1873.[8] By 1890, every Union state had adopted it. The World Wars turned it into a day of remembrance for all members of the U.S. military who fought and died in service. In 1971, Congress standardized the holiday as «Memorial Day» and changed its observance to the last Monday in May.

Two other days celebrate those who have served or are serving in the U.S. military: Armed Forces Day (which is earlier in May), an unofficial U.S. holiday for honoring those currently serving in the armed forces, and Veterans Day (on November 11), which honors all those who have served in the United States Armed Forces.[9]

Claimed origins[edit]

A variety of cities and people have claimed origination of Memorial Day.[10][5][11][12] In some such cases, the claims relate to documented events, occurring before or after the Civil War. Others may stem from general traditions of decorating soldiers’ graves with flowers, rather than specific events leading to the national proclamation.[13] Soldiers’ graves were decorated in the U.S. before[14] and during the American Civil War. Other claims may be less respectable, appearing to some researchers as taking credit without evidence, while erasing better-evidenced events or connections.[8]

[15]

Precedents in the South[edit]

Charleston, South Carolina[edit]

Of documented commemorations occurring after the end of the Civil War and with the same purpose as Logan’s proclamation, the earliest occurred in Charleston, South Carolina. On May 1, 1865, formerly enslaved Black adults and children held a parade of 10,000 people to honor 257 dead Union soldiers. Those soldiers had been buried in a mass grave at the Washington Race Course, having died at the Confederate prison camp located there. After the city fell, recently freed persons unearthed and properly buried the soldiers. Then, on May 1, they held a parade and placed flowers. The estimate of 10,000 people comes from contemporaneous reporting, more recently unearthed by Historian David W. Blight, following references in archived material from Union veterans where the events were also described. Blight cites articles in the Charleston Daily Courier and the New-York Tribune.[16]

No direct link has been established between this event and Logan’s 1868 proclamations. Although Blight has claimed that «African Americans invented Memorial Day in Charleston, South Carolina»,[17] in 2012, he stated that he «has no evidence» that the event in Charleston effectively led to General Logan’s call for the national holiday.[18][15]

85th Anniversary of Memorial Day

Virginia[edit]

On June 3, 1861, Warrenton, Virginia, was the location of the first Civil War soldier’s grave ever to be decorated, according to a Richmond Times-Dispatch newspaper article in 1906.[19] This decoration was for the funeral of the first soldier killed in action during the Civil War, John Quincy Marr, who fought and died on June 1, 1861, during a skirmish at Battle of Fairfax Courthouse in Virginia.[20]

Jackson, Mississippi[edit]

On April 26, 1865, in Jackson, Mississippi, Sue Landon Vaughan supposedly decorated the graves of Confederate and Union soldiers. However, the earliest recorded reference to this event did not appear until many years after.[21] Regardless, mention of the observance is inscribed on the southeast panel of the Confederate Monument in Jackson, erected in 1891.[22]

Columbus, Georgia[edit]

The United States National Park Service[23] and numerous scholars attribute the beginning of a Memorial Day practice in the South to a group of women of Columbus, Georgia.[21][24][25][26][27][28][29] The women were the Ladies Memorial Association of Columbus. They were represented by Mary Ann Williams (Mrs. Charles J. Williams) who, as Secretary, wrote a letter to press in March 1866 asking their assistance in establishing annual holiday to decorate the graves of soldiers throughout the south.[30] The letter was reprinted in several southern states and the plans were noted in newspapers in the north. The date of April 26 was chosen. The holiday was observed in Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, Columbus and elsewhere in Georgia as well as Montgomery, Alabama; Memphis, Tennessee; Louisville, Kentucky; New Orleans, Louisiana; Jackson, Mississippi, and across the south.[21] In some cities, mostly in Virginia, other dates in May and June were observed. General John A. Logan commented on the observances in a speech to veterans on July 4, 1866, in Salem, Illinois.[31] After General Logan’s General Order No. 11 to the Grand Army of the Republic to observe May 30, 1868, the earlier version of the holiday began to be referred to as Confederate Memorial Day.[21]

Columbus, Mississippi[edit]

A year after the war’s end, in April 1866, four women of Columbus gathered together at Friendship Cemetery to decorate the graves of the Confederate soldiers. They also felt moved to honor the Union soldiers buried there, and to note the grief of their families, by decorating their graves as well. The story of their gesture of humanity and reconciliation is held by some writers as the inspiration of the original Memorial Day despite its occurring last among the claimed inspirations.[32][33][34][35]

Other Southern Precedents[edit]

According to the United States Library of Congress website, «Southern women decorated the graves of soldiers even before the Civil War’s end. Records show that by 1865, Mississippi, Virginia, and South Carolina all had precedents for Memorial Day.»[36] The earliest Southern Memorial Day celebrations were simple, somber occasions for veterans and their families to honor the dead and tend to local cemeteries.[37] In following years, the Ladies’ Memorial Association and other groups increasingly focused rituals on preserving Confederate culture and the Lost Cause of the Confederacy narrative.[38]

Precedents in the North[edit]

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania[edit]

The 1863 cemetery dedication at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, included a ceremony of commemoration at the graves of dead soldiers. Some have therefore claimed that President Abraham Lincoln was the founder of Memorial Day.[39] However, Chicago journalist Lloyd Lewis tried to make the case that it was Lincoln’s funeral that spurred the soldiers’ grave decorating that followed.[40]

Boalsburg, Pennsylvania[edit]

On July 4, 1864, ladies decorated soldiers’ graves according to local historians in Boalsburg, Pennsylvania.[41] Boalsburg promotes itself as the birthplace of Memorial Day.[42] However, no published reference to this event has been found earlier than the printing of the History of the 148th Pennsylvania Volunteers in 1904.[43] In a footnote to a story about her brother, Mrs. Sophie (Keller) Hall described how she and Emma Hunter decorated the grave of Emma’s father, Reuben Hunter, and then the graves of all soldiers in the cemetery. The original story did not account for Reuben Hunter’s death occurring two months later on September 19, 1864. It also did not mention Mrs. Elizabeth Myers as one of the original participants. However, a bronze statue of all three women gazing upon Reuben Hunter’s grave now stands near the entrance to the Boalsburg Cemetery. Although July 4, 1864, was a Monday, the town now claims that the original decoration was on one of the Sundays in October 1864.[44]

National Decoration Day[edit]

General John A. Logan, who in 1868 issued a proclamation calling for «Decoration Day»

Orphans placing flags at their fathers’ graves in Glenwood Cemetery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on Decoration Day

On May 5, 1868, General John A. Logan issued a proclamation calling for «Decoration Day» to be observed annually and nationwide; he was commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), an organization of and for Union Civil War veterans founded in Decatur, Illinois.[45] With his proclamation, Logan adopted the Memorial Day practice that had begun in the Southern states three years earlier.[21][46][47][48][30][49][50] The northern states quickly adopted the holiday. In 1868, memorial events were held in 183 cemeteries in 27 states, and 336 in 1869.[51] One author claims that the date was chosen because it was not the anniversary of any particular battle.[52] According to a White House address in 2010, the date was chosen as the optimal date for flowers to be in bloom in the North.[53]

Michigan state holiday[edit]

In 1871, Michigan made Decoration Day an official state holiday and by 1890, every northern state had followed suit. There was no standard program for the ceremonies, but they were typically sponsored by the Women’s Relief Corps, the women’s auxiliary of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which had 100,000 members. By 1870, the remains of nearly 300,000 Union dead had been reinterred in 73 national cemeteries, located near major battlefields and thus mainly in the South. The most famous are Gettysburg National Cemetery in Pennsylvania and Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington, :D.C.[54]

Waterloo, New York proclamation[edit]

On May 26, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson designated an «official» birthplace of the holiday by signing the presidential proclamation naming Waterloo, New York, as the holder of the title. This action followed House Concurrent Resolution 587, in which the 89th Congress had officially recognized that the patriotic tradition of observing Memorial Day had begun one hundred years prior in Waterloo, New York.[55] The village credits druggist Henry C. Welles and county clerk John B. Murray as the founders of the holiday.[citation needed] The legitimacy of this claim has been called into question by several scholars.[56]

Early national history[edit]

In April 1865, following Lincoln’s assassination, commemorations were widespread. The more than 600,000 soldiers of both sides who fought and died in the Civil War meant that burial and memorialization took on new cultural significance. Under the leadership of women during the war, an increasingly formal practice of decorating graves had taken shape. In 1865, the federal government also began creating the United States National Cemetery System for the Union war dead.[57]

By the 1880s, ceremonies were becoming more consistent across geography as the GAR provided handbooks that presented specific procedures, poems, and Bible verses for local post commanders to utilize in planning the local event. Historian Stuart McConnell reports:[58]

on the day itself, the post assembled and marched to the local cemetery to decorate the graves of the fallen, an enterprise meticulously organized months in advance to assure that none were missed. Finally came a simple and subdued graveyard service involving prayers, short patriotic speeches, and music … and at the end perhaps a rifle salute.

Relationship to Confederate Memorial Day[edit]

In 1868, some Southern public figures began adding the label «Confederate» to their commemorations and claimed that Northerners had appropriated the holiday.[59][23][60] The first official celebration of Confederate Memorial Day as a public holiday occurred in 1874, following a proclamation by the Georgia legislature.[61] By 1916, ten states celebrated it, on June 3, the birthday of CSA President Jefferson Davis.[61] Other states chose late April dates, or May 10, commemorating Davis’ capture.[61]

The Ladies’ Memorial Association played a key role in using Memorial Day rituals to preserve Confederate culture.[38] Various dates ranging from April 25 to mid-June were adopted in different Southern states. Across the South, associations were founded, many by women, to establish and care for permanent cemeteries for the Confederate dead, organize commemorative ceremonies, and sponsor appropriate monuments as a permanent way of remembering the Confederate dead. The most important of these was the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which grew frerate South.[37] Changes in the ceremony’s hymns and speeches reflect an evolution of the ritual into a symbol of cultural renewal and conservatism in the South. By 1913, David Blight argues, the theme of American nationalism shared equal time with the Confederate.[62]

Renaming[edit]

By the 20th century, various Union memorial traditions, celebrated on different days, merged, and Memorial Day eventually extended to honor all Americans who fought and died while in the U.S. military service.[2] Indiana from the 1860s to the 1920s saw numerous debates on how to expand the celebration. It was a favorite lobbying activity of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). An 1884 GAR handbook explained that Memorial Day was «the day of all days in the G.A.R. Calendar» in terms of mobilizing public support for pensions. It advised family members to «exercise great care» in keeping the veterans sober.[63]

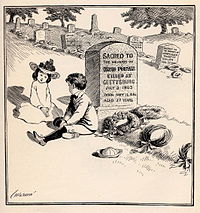

«On Decoration Day» Political cartoon c. 1900 by John T. McCutcheon. Caption: «You bet I’m goin’ to be a soldier, too, like my Uncle David, when I grow up.»

Memorial Day speeches became an occasion for veterans, politicians, and ministers to commemorate the Civil War and, at first, to rehash the «atrocities» of the enemy. They mixed religion and celebratory nationalism for the people to make sense of their history in terms of sacrifice for a better nation. People of all religious beliefs joined and the point was often made that German and Irish soldiers – ethnic minorities which faced discrimination in the United States – had become true Americans in the «baptism of blood» on the battlefield.[64]

In the national capital in 1913 the four-day «Blue-Gray Reunion» featured parades, re-enactments, and speeches from a host of dignitaries, including President Woodrow Wilson, the first Southerner elected to the White House since the War. James Heflin of Alabama gave the main address. Heflin was a noted orator; his choice as Memorial Day speaker was criticized, as he was opposed for his support of segregation; however, his speech was moderate in tone and stressed national unity and goodwill, gaining him praise from newspapers.[65]

The name «Memorial Day», which was first attested in 1882, gradually became more common than «Decoration Day» after World War II[66] but was not declared the official name by federal law until 1967.[67] On June 28, 1968, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, which moved four holidays, including Memorial Day, from their traditional dates to a specified Monday in order to create a convenient three-day weekend.[68] The change moved Memorial Day from its traditional May 30 date to the last Monday in May. The law took effect at the federal level in 1971.[68] After some initial confusion and unwillingness to comply, all 50 states adopted Congress’s change of date within a few years.[citation needed]

By the early 20th century, the GAR complained more and more about the younger generation.[citation needed] In 1913, one Indiana veteran complained that younger people born since the war had a «tendency … to forget the purpose of Memorial Day and make it a day for games, races, and revelry, instead of a day of memory and tears».[69] Indeed, in 1911 the scheduling of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway car race (later named the Indianapolis 500) was vehemently opposed by the increasingly elderly GAR. The state legislature in 1923 rejected holding the race on the holiday. But the new American Legion and local officials wanted the big race to continue, so Governor Warren McCray vetoed the bill and the race went on.[70]

Civil religious holiday[edit]

Memorial Day endures as a holiday which most businesses observe because it marks the unofficial beginning of summer. The Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) and Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUVCW) advocated returning to the original date. The VFW stated in 2002:[71]

Changing the date merely to create three-day weekends has undermined the very meaning of the day. No doubt, this has contributed a lot to the general public’s nonchalant observance of Memorial Day.

In 2000, Congress passed the National Moment of Remembrance Act, asking people to stop and remember at 3:00 pm.[72]

On Memorial Day, the flag of the United States is raised briskly to the top of the staff and then solemnly lowered to the half-staff position, where it remains only until noon.[73] It is then raised to full-staff for the remainder of the day.[74]

Memorial Day observances in small New England towns are often marked by dedications and remarks by veterans and politicians.

The National Memorial Day Concert takes place on the west lawn of the United States Capitol.[75] The concert is broadcast on PBS and NPR. Music is performed, and respect is paid to the people who gave their lives for their country.[citation needed]

Across the United States, the central event is attending one of the thousands of parades held on Memorial Day in large and small cities. Most of these feature marching bands and an overall military theme with the Active Duty, Reserve, National Guard, and Veteran service members participating along with military vehicles from various wars.[citation needed]

Scholars,[76][77][78][79] following the lead of sociologist Robert Bellah, often make the argument that the United States has a secular «civil religion» – one with no association with any religious denomination or viewpoint – that has incorporated Memorial Day as a sacred event. With the Civil War, a new theme of death, sacrifice, and rebirth enters the civil religion. Memorial Day gave ritual expression to these themes, integrating the local community into a sense of nationalism. The American civil religion, in contrast to that of France, was never anticlerical or militantly secular; in contrast to Britain, it was not tied to a specific denomination, such as the Church of England. The Americans borrowed from different religious traditions so that the average American saw no conflict between the two, and deep levels of personal motivation were aligned with attaining national goals.[80]

Longest observance[edit]

Since 1868, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, has held an annual Memorial Day parade which it claims to be the nation’s oldest continuously running. Grafton, West Virginia, has also had an ongoing parade since 1868. However, the Memorial Day parade in Rochester, Wisconsin, predates both the Doylestown and the Grafton parades by one year (1867).[81][82]

Poppies[edit]

In 1915, following the Second Battle of Ypres, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, a physician with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, wrote the poem, «In Flanders Fields». Its opening lines refer to the fields of poppies that grew among the soldiers’ graves in Flanders.[83]

In 1918, inspired by the poem, YWCA worker Moina Michael attended a YWCA Overseas War Secretaries’ conference wearing a silk poppy pinned to her coat and distributed over two dozen more to others present. In 1920, the National American Legion adopted it as its official symbol of remembrance.[84]

Observance dates (1971–2037)[edit]

| Year | Memorial Day | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 1976 | 1982 | 1993 | 1999 | 2004 | 2010 | 2021 | 2027 | 2032 | May 31 (week 22) | ||

| 1977 | 1983 | 1988 | 1994 | 2005 | 2011 | 2016 | 2022 | 2033 | May 30 (week 22) | |||

| 1972 | 1978 | 1989 | 1995 | 2000 | 2006 | 2017 | 2023 | 2028 | 2034 | May 29 (week 22) | ||

| 1973 | 1979 | 1984 | 1990 | 2001 | 2007 | 2012 | 2018 | 2029 | 2035 | May 28 (week 22) | ||

| 1974 | 1985 | 1991 | 1996 | 2002 | 2013 | 2019 | 2024 | 2030 | May 27 (common year week 21, leap year week 22) | |||

| 1975 | 1980 | 1986 | 1997 | 2003 | 2008 | 2014 | 2025 | 2031 | 2036 | May 26 (week 21) | ||

| 1981 | 1987 | 1992 | 1998 | 2009 | 2015 | 2020 | 2026 | 2037 | May 25 (week 21) |

[edit]

Decoration Day (Appalachia and Liberia)[edit]

Decoration Days in Southern Appalachia and Liberia are a tradition which arose by the 19th century. Decoration practices are localized and unique to individual families, cemeteries, and communities, but common elements that unify the various Decoration Day practices are thought to represent syncretism of predominantly Christian cultures in 19th century Southern Appalachia with pre-Christian influences from Scotland, Ireland, and African cultures. Appalachian and Liberian cemetery decoration traditions are thought to have more in common with one another than with United States Memorial Day traditions which are focused on honoring the military dead.[85] Appalachian and Liberian cemetery decoration traditions pre-date the United States Memorial Day holiday.[86]

In the United States, cemetery decoration practices have been recorded in the Appalachian regions of West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, northern South Carolina, northern Georgia, northern and central Alabama, and northern Mississippi. Appalachian cemetery decoration has also been observed in areas outside Appalachia along routes of westward migration from that region: northern Louisiana, northeastern Texas, Arkansas, eastern Oklahoma, and southern Missouri.[citation needed]

According to scholars Alan and Karen Jabbour, «the geographic spread … from the Smokies to northeastern Texas and Liberia, offer strong evidence that the southern Decoration Day originated well back in the nineteenth century. The presence of the same cultural tradition throughout the Upland South argues for the age of the tradition, which was carried westward (and eastward to Africa) by nineteenth-century migration and has survived in essentially the same form till the present.»[45]

While these customs may have inspired in part rituals to honor military dead like Memorial Day, numerous differences exist between Decoration Day customs and Memorial Day, including that the date is set differently by each family or church for each cemetery to coordinate the maintenance, social, and spiritual aspects of decoration.[85][87][88]

In film, literature, and music[edit]

Films[edit]

- In Memorial Day, a 2012 war film starring James Cromwell, Jonathan Bennett, and John Cromwell, a character recalls and relives memories of World War II.

Music[edit]

- Charles Ives’s symphonic 1912 poem Decoration Day depicts the holiday as he experienced it in his childhood, with his father’s band leading the way to the town cemetery, the playing of «Taps» on a trumpet, and a livelier march tune on the way back to the town. It is frequently played with three other Ives works based on holidays, as the second movement of A Symphony: New England Holidays.[citation needed]

- American rock band Drive-By Truckers released a Jason Isbell–penned song titled «Decoration Day» on their 2003 album of the same title.

Poetry[edit]

Poems commemorating Memorial Day include:

- Francis M. Finch’s «The Blue and the Gray» (1867)[89]

- Michael Anania’s «Memorial Day» (1994)[90]

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s «Decoration Day» (1882)[91]

- Joyce Kilmer’s «Memorial Day»[citation needed]

See also[edit]

United States[edit]

- Remembrance Day at the Gettysburg Battlefield, an annual honoring of Civil War dead held near the anniversary of the Gettysburg Address

- A Great Jubilee Day, first held the last Monday in May 1783 (American Revolutionary War)

- Armed Forces Day, third Saturday in May, a more narrowly observed remembrance honoring those currently serving in the U.S. military

- Armistice Day, November 11, the original name of Veterans Day in the United States

- Confederate Memorial Day, observed on various dates in many states in the South in memory of those killed fighting for the Confederacy during the American Civil War

- Memorial Day massacre of 1937, May 30, held to remember demonstrators shot by police in Chicago

- Nora Fontaine Davidson, credited with the first Memorial Day ceremony in Petersburg, Virginia

- Patriot Day, September 11, in memory of people killed in the September 11, 2001 attacks

- United States military casualties of war

- Veterans Day, November 11, in memory of American military deaths during World War I. See Remembrance Day for similar observances in Canada, the United Kingdom, and other Commonwealth nations.

Other countries[edit]

- ANZAC Day, April 25, an analogous observance in Australia and New Zealand

- Armistice Day, November 11, the original name of Veterans Day in the United States and Remembrance Day in Canada, the United Kingdom, and other Commonwealth nations

- Heroes’ Day, various dates in various countries recognizing national heroes

- International Day of United Nations Peacekeepers, May 29, international observance recognizing United Nations peacekeepers

- Remembrance Day, November 11, a similar observance in Canada, the United Kingdom, and many other Commonwealth nations originally marking the end of World War I

- Remembrance of the Dead («Dodenherdenking»), May 4, a similar observance in the Netherlands

- Volkstrauertag («People’s Mourning Day»), a similar observance in Germany usually in November

- Yom Hazikaron (Israeli memorial day), the day before Independence Day (Israel), around Iyar 4

- Decoration Day (Canada), a Canadian holiday that recognizes veterans of Canada’s military which has largely been eclipsed by the similar Remembrance Day

- Memorial Day (South Korea), June 6, the day to commemorate the men and women who died while in military service during the Korean War and other significant wars or battles

- Victoria Day, a Canadian holiday on the last Monday before May 25 each year, lacks the military memorial aspects of Memorial Day but serves a similar function as marking the start of cultural summer

References[edit]

- ^ «Memorial Day». History.com.

- ^ a b «Memorial Day». United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ 36 U.S.C. § 116

- ^ Yan, Holly (May 26, 2016). «Memorial Day 2016: What you need to know». CNN. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ a b «Today in History — May 30». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Administration, National Cemetery. ««Memorial Day Order» — National Cemetery Administration». www.cem.va.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ «Memorial Day History». cem.va.gov. May 26, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Administration, National Cemetery. «Memorial Day History — National Cemetery Administration». www.cem.va.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Kickler, Sarah (May 28, 2012). «Memorial Day vs. Veterans Day». baltimoresun.com. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ «Memorial Day History». U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ Klein, Christopher. «Where Did Memorial Day Originate?». HISTORY. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ «The Center for Civil War Research». www.civilwarcenter.olemiss.edu. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Mary L’Hommedieu Gardiner (1842). «The Ladies Garland». J. Libby. p. 296. Retrieved May 31, 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ In 1817, for example, a writer in the Analectic Magazine of Philadelphia urged the decoration of patriot’s graves. E.J., «The Soldier’s Grave,» in The Analectic Magazine (1817), Vol. 10, 264.

- ^ a b «The Origins of Memorial Day» Snopes.com, May 25, 2018

- ^ Roos, Dave. «One of the Earliest Memorial Day Ceremonies Was Held by Freed African Americans». HISTORY. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Blight, David W. «Lecture: To Appomattox and Beyond: The End of the War and a Search for Meanings, Overview». Oyc.yale.edu. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

Professor Blight closes his lecture with a description of the first Memorial Day, celebrated by African Americans in Charleston, SC 1865.

- ^ David Blight, cited by Campbell Robertson, «Birthplace of Memorial Day? That Depends Where You’re From,» New York Times, May 28, 2012 – Blight quote from 2nd web page: «He has called that the first Memorial Day, as it predated most of the other contenders, though he said he has no evidence that it led to General Logan’s call for a national holiday.»

- ^ «Times-Dispatch». Perseus.tufts.edu. July 15, 1906. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Poland Jr., Charles P. The Glories Of War: Small Battle And Early Heroes Of 1861. Bloomington, IN (2006), 42.

- ^ a b c d e Bellware, Daniel (2014). The Genesis of the Memorial Day holiday in America. ISBN 9780692292259. OCLC 898066352.

- ^ «Mississippi Confederate Monument – Jackson, MS». Waymarking.com. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ a b National Park Service, «Flowers For Jennie» Retrieved February 24, 2015

- ^ Gallagher, Gary W.; Nolan, Alan T. (2000). The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253109026. Retrieved May 25, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Johnson, Kristina Dunn (2009). No Holier Spot of Ground: Confederate Monuments & Cemeteries of South Carolina. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781614232827. Retrieved May 25, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kammen, Michael (2011). Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307761408. Retrieved May 25, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ English, Tom. «A ‘complicated’ journey: The story of Logan and Memorial Day». The Southern. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Logan, Mrs. John A. (1913). Mrs. Logan’s Memoirs. p. 246. Retrieved April 7, 2014 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ «Birthplace of Memorial Day? That Depends Where You’re From». The New York Times. May 27, 2012.

- ^ a b «Memorial Day’s Roots Traced To Georgia» Michael Jones, Northwest Herald, May 23, 2015.

- ^ Brockell, Gillian (May 27, 2019). «Memorial Day’s Confederate Roots: Who Really Invented the Holiday?». The Washington Post. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Fallows, Deborah (May 23, 2014). «A Real Story of Memorial Day». The Atlantic. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Adams, Will (May 25, 2017). «Decoration Day & The Origins Of Memorial Day». RelicRecord. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ «Confederate Decoration Day Historical Marker». Hmdb.org. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ «MSU library, Ole Miss anthropologist, local historian search for Union graves». The Clarion Ledger. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ «Today in History – May 30 – Memorial Day». United States Library of Congress. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ a b University of Michigan; EBSCO Publishing (Firm) (2000). America, history and life. Clio Press. p. 190.

- ^ a b Karen L. Cox (2003). Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Universbuttse Memorial Day. ISBN 978-0813031330.

- ^ «Lincoln’s Message to Today,» Trenton (NJ) Evening Times, May 30, 1913.

- ^ Lloyd, Lewis (1941). Myths After Lincoln. New York: Press of the Readers Club. pp. 309–10.[ISBN missing]

- ^ «Sophie Keller Hall, in The Story of Our Regiment: A History of the 148th Pennsylvania Vols., ed. J.W. Muffly (Des Moines: The Kenyon Printing & Mfg. Co., 1904), quoted in editor’s note, p. 45». Civilwarcenter.olemiss.edu. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ «Boalsburg, PA, birthplace of Memorial Day». Boalsburg.com. March 26, 1997.

- ^ Muffly, J. W. (Joseph Wendel) (1904). The story of our Regiment : a history of the 148th Pennsylvania Vols. Butternut and Blue. p. 45. ISBN 0935523391. OCLC 33463683.

- ^ Flynn, Michael (2010). «Boalsburg and the Origin of Memorial Day». Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Alan Jabbour; Karen Singer Jabbour (2010). Decoration Day in the Mountains: Traditions of Cemetery Decoration in the Southern Appalachians. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8078-3397-1. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ P. Michael Jones, Daniel Bellware, and Richard Gardiner (Spring–Summer 2018). «The Emergence and Evolution of Memorial Day». Journal of America’s Military Past. 43–2 (137): 19–37. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Logan, Mrs. John A. (1913). General John Logan, quoted by his wife. Retrieved April 7, 2014 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ «A Complicated Journey: The Story of Logan and Memorial Day» Tom English, The Southern Illinoisian, May 22, 2015

- ^ Halstead, Marilyn. «Did Logan start Memorial Day? Logan museum director invites visitors to decide». thesouthern.com.

- ^ WTOP (May 25, 2018). «The forgotten history of Memorial Day». wtop.com.

- ^ Blight (2004), pp. 99–100

- ^ Cohen, Hennig; Coffin, Tristram Potter (1991). The Folklore of American holidays. p. 215. ISBN 978-0810376021 – via Gale Research.

- ^ «Barack Obama, Weekly Address» (transcript). Whitehouse.gov. May 29, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2014 – via National Archives.

- ^ «Interments in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Cemeteries» (PDF). Washington, DC: National Cemetery Administration – Department of Veterans Affairs VA-NCA-IS-1. January 2011.

After the Civil War, search and recovery teams visited hundreds of battlefields, churchyards, plantations and other locations seeking wartime interments that were made in haste. By 1870, the remains of nearly 300,000 Civil War dead were reinterred in 73 national cemeteries.

- ^ Johnson, Lyndon. «Presidential Proclamation 3727». Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ «The origin of Memorial Day: Is Waterloo’s claim to fame the result of a simple newspaper typo?»

- ^ Joan Waugh; Gary W. Gallagher (2009). Wars Within a War: Controversy and Conflict Over the American Civil War. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8078-3275-2.

- ^ Stuart McConnell (1997). Glorious Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic, 1865–1900 p. 184.ISBN 978-0807846285

- ^ Gardiner and Bellware, p. 87

- ^ Lucian Lamar Knight (1914). Memorial Day: Its True History. Retrieved May 28, 2012 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ a b c «Confederate Memorial Day in Georgia». GeorgiaInfo. University of Georgia. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ David W. Blight (2001). Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Harvard U.P. p. 265. ISBN 978-0674022096.

- ^ Nicholas W. Sacco, «The Grand Army of the Republic, the Indianapolis 500, and the Struggle for Memorial Day in Indiana, 1868–1923.» Indiana Magazine of History 111.4 (2015): 349–380, at p. 352

- ^ Samito, Christian G. (2009). Becoming American Under Fire: Irish Americans, African Americans, and the Politics of Citizenship During the Civil War Era. Cornell University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8014-4846-1. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ G. Allan Yeomans, «A Southern Segregationist Goes to Gettysburg,» Alabama Historical Quarterly (1972) 34#3 pp. 194–205.

- ^ Henry Perkins Goddard; Calvin Goddard Zon (2008). The Good Fight That Didn’t End: Henry P. Goddard’s Accounts of Civil War and Peace. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-57003-772-6.

- ^ Alan Axelrod (2007). Miracle at Belleau Wood: The Birth of the Modern U.S. Marine Corps. Globe Pequot. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-59921-025-4.

- ^ a b «Public Law 90-363». Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Sacco, p. 362

- ^ Sacco, p. 376

- ^ Mechant, David (April 28, 2007). «Memorial Day History». Archived from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ Scott, Ryan (May 24, 2015). «Memorial Day, 3 p.m.: Don’t Forget». Forbes. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ Peggy Post; Anna Post; Lizzie Post; Daniel Post Senning (2011). Emily Post’s Etiquette, 18. HarperCollins. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-06-210127-3.

- ^ Congress (2009). United States Code, 2006, Supplement 1, January 4, 2007, to January 8, 2008. Government Printing Office. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-16-083512-4.

- ^ «The National Memorial Day Concert» pbs.org, May 25, 2018

- ^ William H. Swatos; Peter Kivisto (1998). Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Rowman Altamira. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1.

- ^ Marcela Cristi (2001). From Civil to Political Religion: The Intersection of Culture, Religion and Politics. Wilfrid Laurier U.P. pp. 48–53. ISBN 978-0-88920-368-6.

- ^ William M. Epstein (2002). American Policy Making: Welfare As Ritual. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7425-1733-2.

- ^ Corwin E. Smidt; Lyman A. Kellstedt; James L. Guth (2009). The Oxford Handbook of Religion and American Politics. Oxford Handbooks Online. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-19-532652-9.

- ^ Robert N. Bellah, «Civil Religion in America», Daedalus 1967 96(1): 1–21.

- ^ Knapp, Aaron. «Rochester commemorates fallen soldiers in 150th Memorial Day parade». Journal Times. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- ^ says, Lisa (May 29, 2011). «Doylestown Hosts Oldest Memorial Day Parade In The Country». Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (October 28, 2014). World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection [5 volumes]: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1061–. ISBN 978-1-85109-965-8.

- ^ «Where did the idea to sell poppies come from?». BBC News. November 10, 2006. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Jabbour, Alan (May 27, 2010). «What is Decoration Day?». University of North Carolina Blog. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ «Decoration Day». Encyclopedia of Alabama. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Hooker, Elizabeth R. (1933). Religion in the Highlands: Native Churches and Missionary Enterprises in the Southern Appalachian Area. New York: Home Mission Council. p. 125.

- ^ Meyer, Richard E. American Folklore: An Encyclopedia – Cemeteries. pp. 132–34.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Finch, Francis (1867). «Blue and the Gray». civilwarhome.

- ^ Anania, Michael (1994). «Memorial Day». PoetryFoundation.

- ^ Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. «Memorial Day». The Atlantic.

Further reading[edit]

- Albanese, Catherine. «Requiem for Memorial Day: Dissent in the Redeemer Nation», American Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Oct. 1974), pp. 386–398 in JSTOR

- Bellah, Robert N. «Civil Religion in America». Daedalus 1967 96(1): 1–21. online edition

- Bellware, Daniel, and Richard Gardiner, The Genesis of the Memorial Day Holiday in America (Columbus State University, 2014).

- Blight, David W. «Decoration Day: The Origins of Memorial Day in North and South» in Alice Fahs and Joan Waugh, eds. The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture (2004), online edition pp. 94–129; the standard scholarly history

- Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2000) ch. 3, «Decorations» excerpt and text search

- Buck, Paul H. The Road to Reunion, 1865–1900 (1937)[ISBN missing]

- Cherry, Conrad. «Two American Sacred Ceremonies: Their Implications for the Study of Religion in America», American Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Winter, 1969), pp. 739–754 in JSTOR

- Dennis, Matthew. Red, White, and Blue Letter Days: An American Calendar (2002)[ISBN missing]

- Jabbour, Alan, and Karen Singer Jabbour. Decoration Day in the Mountains: Traditions of Cemetery Decoration in the Southern Appalachians (University of North Carolina Press; 2010)[ISBN missing]

- Myers, Robert J. «Memorial Day». Chapter 24 in Celebrations: The Complete Book of American Holidays. (1972)[ISBN missing]

- Robert Haven Schauffler (1911). Memorial Day: Its Celebration, Spirit, and Significance as Related in Prose and Verse, with a Non-sectional Anthology of the Civil War. BiblioBazaar reprint 2010. ISBN 9781176839045.

External links[edit]

- 36 USC 116. Memorial Day (designation law)

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs

| Memorial Day | |

|---|---|

The gravestones at Arlington National Cemetery are decorated with U.S. flags during Memorial Day weekend of 2008. |

|

| Official name | Memorial Day |

| Observed by | Americans |

| Type | Federal |

| Observances | U.S. military personnel who died in service |

| Date | Last Monday in May |

| 2022 date | May 30 |

| 2023 date | May 29 |

| 2024 date | May 27 |

| 2025 date | May 26 |

| Frequency | Annual |

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day[1]) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have died while serving in the United States armed forces.[2] It is observed on the last Monday of May. From 1868 to 1970 it was observed on May 30.[3]

Many people visit cemeteries and memorials on Memorial Day to honor and mourn those who died while serving in the U.S. military. Many volunteers place American flags on the graves of military personnel in national cemeteries. Memorial Day is also considered the unofficial beginning of summer in the United States.[4]

The first national observance of Memorial Day occurred on May 30, 1868.[5] Then known as Decoration Day, the holiday was proclaimed by Commander in Chief John A. Logan of the Grand Army of the Republic to honor the Union soldiers who had died in the Civil War.[6] This national observance was preceded by many local ones between the end of the Civil War and Logan’s declaration. Many cities and people have claimed to be the first to observe it. However, in 2022, the National Cemetery Administration, a division of the Department of Veterans Affairs, credited Mary Ann Williams with originating the «idea of strewing the graves of Civil War soldiers — Union and Confederate» with flowers.[7]

Official recognition as a holiday spread among the states, beginning with New York in 1873.[8] By 1890, every Union state had adopted it. The World Wars turned it into a day of remembrance for all members of the U.S. military who fought and died in service. In 1971, Congress standardized the holiday as «Memorial Day» and changed its observance to the last Monday in May.

Two other days celebrate those who have served or are serving in the U.S. military: Armed Forces Day (which is earlier in May), an unofficial U.S. holiday for honoring those currently serving in the armed forces, and Veterans Day (on November 11), which honors all those who have served in the United States Armed Forces.[9]

Claimed origins[edit]

A variety of cities and people have claimed origination of Memorial Day.[10][5][11][12] In some such cases, the claims relate to documented events, occurring before or after the Civil War. Others may stem from general traditions of decorating soldiers’ graves with flowers, rather than specific events leading to the national proclamation.[13] Soldiers’ graves were decorated in the U.S. before[14] and during the American Civil War. Other claims may be less respectable, appearing to some researchers as taking credit without evidence, while erasing better-evidenced events or connections.[8]

[15]

Precedents in the South[edit]

Charleston, South Carolina[edit]

Of documented commemorations occurring after the end of the Civil War and with the same purpose as Logan’s proclamation, the earliest occurred in Charleston, South Carolina. On May 1, 1865, formerly enslaved Black adults and children held a parade of 10,000 people to honor 257 dead Union soldiers. Those soldiers had been buried in a mass grave at the Washington Race Course, having died at the Confederate prison camp located there. After the city fell, recently freed persons unearthed and properly buried the soldiers. Then, on May 1, they held a parade and placed flowers. The estimate of 10,000 people comes from contemporaneous reporting, more recently unearthed by Historian David W. Blight, following references in archived material from Union veterans where the events were also described. Blight cites articles in the Charleston Daily Courier and the New-York Tribune.[16]

No direct link has been established between this event and Logan’s 1868 proclamations. Although Blight has claimed that «African Americans invented Memorial Day in Charleston, South Carolina»,[17] in 2012, he stated that he «has no evidence» that the event in Charleston effectively led to General Logan’s call for the national holiday.[18][15]

85th Anniversary of Memorial Day

Virginia[edit]

On June 3, 1861, Warrenton, Virginia, was the location of the first Civil War soldier’s grave ever to be decorated, according to a Richmond Times-Dispatch newspaper article in 1906.[19] This decoration was for the funeral of the first soldier killed in action during the Civil War, John Quincy Marr, who fought and died on June 1, 1861, during a skirmish at Battle of Fairfax Courthouse in Virginia.[20]

Jackson, Mississippi[edit]

On April 26, 1865, in Jackson, Mississippi, Sue Landon Vaughan supposedly decorated the graves of Confederate and Union soldiers. However, the earliest recorded reference to this event did not appear until many years after.[21] Regardless, mention of the observance is inscribed on the southeast panel of the Confederate Monument in Jackson, erected in 1891.[22]

Columbus, Georgia[edit]

The United States National Park Service[23] and numerous scholars attribute the beginning of a Memorial Day practice in the South to a group of women of Columbus, Georgia.[21][24][25][26][27][28][29] The women were the Ladies Memorial Association of Columbus. They were represented by Mary Ann Williams (Mrs. Charles J. Williams) who, as Secretary, wrote a letter to press in March 1866 asking their assistance in establishing annual holiday to decorate the graves of soldiers throughout the south.[30] The letter was reprinted in several southern states and the plans were noted in newspapers in the north. The date of April 26 was chosen. The holiday was observed in Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, Columbus and elsewhere in Georgia as well as Montgomery, Alabama; Memphis, Tennessee; Louisville, Kentucky; New Orleans, Louisiana; Jackson, Mississippi, and across the south.[21] In some cities, mostly in Virginia, other dates in May and June were observed. General John A. Logan commented on the observances in a speech to veterans on July 4, 1866, in Salem, Illinois.[31] After General Logan’s General Order No. 11 to the Grand Army of the Republic to observe May 30, 1868, the earlier version of the holiday began to be referred to as Confederate Memorial Day.[21]

Columbus, Mississippi[edit]

A year after the war’s end, in April 1866, four women of Columbus gathered together at Friendship Cemetery to decorate the graves of the Confederate soldiers. They also felt moved to honor the Union soldiers buried there, and to note the grief of their families, by decorating their graves as well. The story of their gesture of humanity and reconciliation is held by some writers as the inspiration of the original Memorial Day despite its occurring last among the claimed inspirations.[32][33][34][35]

Other Southern Precedents[edit]

According to the United States Library of Congress website, «Southern women decorated the graves of soldiers even before the Civil War’s end. Records show that by 1865, Mississippi, Virginia, and South Carolina all had precedents for Memorial Day.»[36] The earliest Southern Memorial Day celebrations were simple, somber occasions for veterans and their families to honor the dead and tend to local cemeteries.[37] In following years, the Ladies’ Memorial Association and other groups increasingly focused rituals on preserving Confederate culture and the Lost Cause of the Confederacy narrative.[38]

Precedents in the North[edit]

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania[edit]

The 1863 cemetery dedication at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, included a ceremony of commemoration at the graves of dead soldiers. Some have therefore claimed that President Abraham Lincoln was the founder of Memorial Day.[39] However, Chicago journalist Lloyd Lewis tried to make the case that it was Lincoln’s funeral that spurred the soldiers’ grave decorating that followed.[40]

Boalsburg, Pennsylvania[edit]

On July 4, 1864, ladies decorated soldiers’ graves according to local historians in Boalsburg, Pennsylvania.[41] Boalsburg promotes itself as the birthplace of Memorial Day.[42] However, no published reference to this event has been found earlier than the printing of the History of the 148th Pennsylvania Volunteers in 1904.[43] In a footnote to a story about her brother, Mrs. Sophie (Keller) Hall described how she and Emma Hunter decorated the grave of Emma’s father, Reuben Hunter, and then the graves of all soldiers in the cemetery. The original story did not account for Reuben Hunter’s death occurring two months later on September 19, 1864. It also did not mention Mrs. Elizabeth Myers as one of the original participants. However, a bronze statue of all three women gazing upon Reuben Hunter’s grave now stands near the entrance to the Boalsburg Cemetery. Although July 4, 1864, was a Monday, the town now claims that the original decoration was on one of the Sundays in October 1864.[44]

National Decoration Day[edit]

General John A. Logan, who in 1868 issued a proclamation calling for «Decoration Day»

Orphans placing flags at their fathers’ graves in Glenwood Cemetery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on Decoration Day

On May 5, 1868, General John A. Logan issued a proclamation calling for «Decoration Day» to be observed annually and nationwide; he was commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), an organization of and for Union Civil War veterans founded in Decatur, Illinois.[45] With his proclamation, Logan adopted the Memorial Day practice that had begun in the Southern states three years earlier.[21][46][47][48][30][49][50] The northern states quickly adopted the holiday. In 1868, memorial events were held in 183 cemeteries in 27 states, and 336 in 1869.[51] One author claims that the date was chosen because it was not the anniversary of any particular battle.[52] According to a White House address in 2010, the date was chosen as the optimal date for flowers to be in bloom in the North.[53]

Michigan state holiday[edit]

In 1871, Michigan made Decoration Day an official state holiday and by 1890, every northern state had followed suit. There was no standard program for the ceremonies, but they were typically sponsored by the Women’s Relief Corps, the women’s auxiliary of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which had 100,000 members. By 1870, the remains of nearly 300,000 Union dead had been reinterred in 73 national cemeteries, located near major battlefields and thus mainly in the South. The most famous are Gettysburg National Cemetery in Pennsylvania and Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington, :D.C.[54]

Waterloo, New York proclamation[edit]

On May 26, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson designated an «official» birthplace of the holiday by signing the presidential proclamation naming Waterloo, New York, as the holder of the title. This action followed House Concurrent Resolution 587, in which the 89th Congress had officially recognized that the patriotic tradition of observing Memorial Day had begun one hundred years prior in Waterloo, New York.[55] The village credits druggist Henry C. Welles and county clerk John B. Murray as the founders of the holiday.[citation needed] The legitimacy of this claim has been called into question by several scholars.[56]

Early national history[edit]

In April 1865, following Lincoln’s assassination, commemorations were widespread. The more than 600,000 soldiers of both sides who fought and died in the Civil War meant that burial and memorialization took on new cultural significance. Under the leadership of women during the war, an increasingly formal practice of decorating graves had taken shape. In 1865, the federal government also began creating the United States National Cemetery System for the Union war dead.[57]

By the 1880s, ceremonies were becoming more consistent across geography as the GAR provided handbooks that presented specific procedures, poems, and Bible verses for local post commanders to utilize in planning the local event. Historian Stuart McConnell reports:[58]

on the day itself, the post assembled and marched to the local cemetery to decorate the graves of the fallen, an enterprise meticulously organized months in advance to assure that none were missed. Finally came a simple and subdued graveyard service involving prayers, short patriotic speeches, and music … and at the end perhaps a rifle salute.

Relationship to Confederate Memorial Day[edit]

In 1868, some Southern public figures began adding the label «Confederate» to their commemorations and claimed that Northerners had appropriated the holiday.[59][23][60] The first official celebration of Confederate Memorial Day as a public holiday occurred in 1874, following a proclamation by the Georgia legislature.[61] By 1916, ten states celebrated it, on June 3, the birthday of CSA President Jefferson Davis.[61] Other states chose late April dates, or May 10, commemorating Davis’ capture.[61]

The Ladies’ Memorial Association played a key role in using Memorial Day rituals to preserve Confederate culture.[38] Various dates ranging from April 25 to mid-June were adopted in different Southern states. Across the South, associations were founded, many by women, to establish and care for permanent cemeteries for the Confederate dead, organize commemorative ceremonies, and sponsor appropriate monuments as a permanent way of remembering the Confederate dead. The most important of these was the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which grew frerate South.[37] Changes in the ceremony’s hymns and speeches reflect an evolution of the ritual into a symbol of cultural renewal and conservatism in the South. By 1913, David Blight argues, the theme of American nationalism shared equal time with the Confederate.[62]

Renaming[edit]

By the 20th century, various Union memorial traditions, celebrated on different days, merged, and Memorial Day eventually extended to honor all Americans who fought and died while in the U.S. military service.[2] Indiana from the 1860s to the 1920s saw numerous debates on how to expand the celebration. It was a favorite lobbying activity of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). An 1884 GAR handbook explained that Memorial Day was «the day of all days in the G.A.R. Calendar» in terms of mobilizing public support for pensions. It advised family members to «exercise great care» in keeping the veterans sober.[63]

«On Decoration Day» Political cartoon c. 1900 by John T. McCutcheon. Caption: «You bet I’m goin’ to be a soldier, too, like my Uncle David, when I grow up.»

Memorial Day speeches became an occasion for veterans, politicians, and ministers to commemorate the Civil War and, at first, to rehash the «atrocities» of the enemy. They mixed religion and celebratory nationalism for the people to make sense of their history in terms of sacrifice for a better nation. People of all religious beliefs joined and the point was often made that German and Irish soldiers – ethnic minorities which faced discrimination in the United States – had become true Americans in the «baptism of blood» on the battlefield.[64]

In the national capital in 1913 the four-day «Blue-Gray Reunion» featured parades, re-enactments, and speeches from a host of dignitaries, including President Woodrow Wilson, the first Southerner elected to the White House since the War. James Heflin of Alabama gave the main address. Heflin was a noted orator; his choice as Memorial Day speaker was criticized, as he was opposed for his support of segregation; however, his speech was moderate in tone and stressed national unity and goodwill, gaining him praise from newspapers.[65]

The name «Memorial Day», which was first attested in 1882, gradually became more common than «Decoration Day» after World War II[66] but was not declared the official name by federal law until 1967.[67] On June 28, 1968, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, which moved four holidays, including Memorial Day, from their traditional dates to a specified Monday in order to create a convenient three-day weekend.[68] The change moved Memorial Day from its traditional May 30 date to the last Monday in May. The law took effect at the federal level in 1971.[68] After some initial confusion and unwillingness to comply, all 50 states adopted Congress’s change of date within a few years.[citation needed]

By the early 20th century, the GAR complained more and more about the younger generation.[citation needed] In 1913, one Indiana veteran complained that younger people born since the war had a «tendency … to forget the purpose of Memorial Day and make it a day for games, races, and revelry, instead of a day of memory and tears».[69] Indeed, in 1911 the scheduling of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway car race (later named the Indianapolis 500) was vehemently opposed by the increasingly elderly GAR. The state legislature in 1923 rejected holding the race on the holiday. But the new American Legion and local officials wanted the big race to continue, so Governor Warren McCray vetoed the bill and the race went on.[70]

Civil religious holiday[edit]

Memorial Day endures as a holiday which most businesses observe because it marks the unofficial beginning of summer. The Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) and Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUVCW) advocated returning to the original date. The VFW stated in 2002:[71]

Changing the date merely to create three-day weekends has undermined the very meaning of the day. No doubt, this has contributed a lot to the general public’s nonchalant observance of Memorial Day.

In 2000, Congress passed the National Moment of Remembrance Act, asking people to stop and remember at 3:00 pm.[72]

On Memorial Day, the flag of the United States is raised briskly to the top of the staff and then solemnly lowered to the half-staff position, where it remains only until noon.[73] It is then raised to full-staff for the remainder of the day.[74]

Memorial Day observances in small New England towns are often marked by dedications and remarks by veterans and politicians.

The National Memorial Day Concert takes place on the west lawn of the United States Capitol.[75] The concert is broadcast on PBS and NPR. Music is performed, and respect is paid to the people who gave their lives for their country.[citation needed]

Across the United States, the central event is attending one of the thousands of parades held on Memorial Day in large and small cities. Most of these feature marching bands and an overall military theme with the Active Duty, Reserve, National Guard, and Veteran service members participating along with military vehicles from various wars.[citation needed]

Scholars,[76][77][78][79] following the lead of sociologist Robert Bellah, often make the argument that the United States has a secular «civil religion» – one with no association with any religious denomination or viewpoint – that has incorporated Memorial Day as a sacred event. With the Civil War, a new theme of death, sacrifice, and rebirth enters the civil religion. Memorial Day gave ritual expression to these themes, integrating the local community into a sense of nationalism. The American civil religion, in contrast to that of France, was never anticlerical or militantly secular; in contrast to Britain, it was not tied to a specific denomination, such as the Church of England. The Americans borrowed from different religious traditions so that the average American saw no conflict between the two, and deep levels of personal motivation were aligned with attaining national goals.[80]

Longest observance[edit]

Since 1868, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, has held an annual Memorial Day parade which it claims to be the nation’s oldest continuously running. Grafton, West Virginia, has also had an ongoing parade since 1868. However, the Memorial Day parade in Rochester, Wisconsin, predates both the Doylestown and the Grafton parades by one year (1867).[81][82]

Poppies[edit]

In 1915, following the Second Battle of Ypres, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, a physician with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, wrote the poem, «In Flanders Fields». Its opening lines refer to the fields of poppies that grew among the soldiers’ graves in Flanders.[83]

In 1918, inspired by the poem, YWCA worker Moina Michael attended a YWCA Overseas War Secretaries’ conference wearing a silk poppy pinned to her coat and distributed over two dozen more to others present. In 1920, the National American Legion adopted it as its official symbol of remembrance.[84]

Observance dates (1971–2037)[edit]

| Year | Memorial Day | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 1976 | 1982 | 1993 | 1999 | 2004 | 2010 | 2021 | 2027 | 2032 | May 31 (week 22) | ||

| 1977 | 1983 | 1988 | 1994 | 2005 | 2011 | 2016 | 2022 | 2033 | May 30 (week 22) | |||

| 1972 | 1978 | 1989 | 1995 | 2000 | 2006 | 2017 | 2023 | 2028 | 2034 | May 29 (week 22) | ||

| 1973 | 1979 | 1984 | 1990 | 2001 | 2007 | 2012 | 2018 | 2029 | 2035 | May 28 (week 22) | ||

| 1974 | 1985 | 1991 | 1996 | 2002 | 2013 | 2019 | 2024 | 2030 | May 27 (common year week 21, leap year week 22) | |||

| 1975 | 1980 | 1986 | 1997 | 2003 | 2008 | 2014 | 2025 | 2031 | 2036 | May 26 (week 21) | ||

| 1981 | 1987 | 1992 | 1998 | 2009 | 2015 | 2020 | 2026 | 2037 | May 25 (week 21) |

[edit]

Decoration Day (Appalachia and Liberia)[edit]

Decoration Days in Southern Appalachia and Liberia are a tradition which arose by the 19th century. Decoration practices are localized and unique to individual families, cemeteries, and communities, but common elements that unify the various Decoration Day practices are thought to represent syncretism of predominantly Christian cultures in 19th century Southern Appalachia with pre-Christian influences from Scotland, Ireland, and African cultures. Appalachian and Liberian cemetery decoration traditions are thought to have more in common with one another than with United States Memorial Day traditions which are focused on honoring the military dead.[85] Appalachian and Liberian cemetery decoration traditions pre-date the United States Memorial Day holiday.[86]

In the United States, cemetery decoration practices have been recorded in the Appalachian regions of West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, northern South Carolina, northern Georgia, northern and central Alabama, and northern Mississippi. Appalachian cemetery decoration has also been observed in areas outside Appalachia along routes of westward migration from that region: northern Louisiana, northeastern Texas, Arkansas, eastern Oklahoma, and southern Missouri.[citation needed]

According to scholars Alan and Karen Jabbour, «the geographic spread … from the Smokies to northeastern Texas and Liberia, offer strong evidence that the southern Decoration Day originated well back in the nineteenth century. The presence of the same cultural tradition throughout the Upland South argues for the age of the tradition, which was carried westward (and eastward to Africa) by nineteenth-century migration and has survived in essentially the same form till the present.»[45]

While these customs may have inspired in part rituals to honor military dead like Memorial Day, numerous differences exist between Decoration Day customs and Memorial Day, including that the date is set differently by each family or church for each cemetery to coordinate the maintenance, social, and spiritual aspects of decoration.[85][87][88]

In film, literature, and music[edit]

Films[edit]

- In Memorial Day, a 2012 war film starring James Cromwell, Jonathan Bennett, and John Cromwell, a character recalls and relives memories of World War II.

Music[edit]

- Charles Ives’s symphonic 1912 poem Decoration Day depicts the holiday as he experienced it in his childhood, with his father’s band leading the way to the town cemetery, the playing of «Taps» on a trumpet, and a livelier march tune on the way back to the town. It is frequently played with three other Ives works based on holidays, as the second movement of A Symphony: New England Holidays.[citation needed]

- American rock band Drive-By Truckers released a Jason Isbell–penned song titled «Decoration Day» on their 2003 album of the same title.

Poetry[edit]

Poems commemorating Memorial Day include:

- Francis M. Finch’s «The Blue and the Gray» (1867)[89]

- Michael Anania’s «Memorial Day» (1994)[90]

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s «Decoration Day» (1882)[91]

- Joyce Kilmer’s «Memorial Day»[citation needed]

See also[edit]

United States[edit]

- Remembrance Day at the Gettysburg Battlefield, an annual honoring of Civil War dead held near the anniversary of the Gettysburg Address

- A Great Jubilee Day, first held the last Monday in May 1783 (American Revolutionary War)

- Armed Forces Day, third Saturday in May, a more narrowly observed remembrance honoring those currently serving in the U.S. military

- Armistice Day, November 11, the original name of Veterans Day in the United States

- Confederate Memorial Day, observed on various dates in many states in the South in memory of those killed fighting for the Confederacy during the American Civil War

- Memorial Day massacre of 1937, May 30, held to remember demonstrators shot by police in Chicago

- Nora Fontaine Davidson, credited with the first Memorial Day ceremony in Petersburg, Virginia

- Patriot Day, September 11, in memory of people killed in the September 11, 2001 attacks

- United States military casualties of war

- Veterans Day, November 11, in memory of American military deaths during World War I. See Remembrance Day for similar observances in Canada, the United Kingdom, and other Commonwealth nations.

Other countries[edit]

- ANZAC Day, April 25, an analogous observance in Australia and New Zealand

- Armistice Day, November 11, the original name of Veterans Day in the United States and Remembrance Day in Canada, the United Kingdom, and other Commonwealth nations

- Heroes’ Day, various dates in various countries recognizing national heroes

- International Day of United Nations Peacekeepers, May 29, international observance recognizing United Nations peacekeepers

- Remembrance Day, November 11, a similar observance in Canada, the United Kingdom, and many other Commonwealth nations originally marking the end of World War I

- Remembrance of the Dead («Dodenherdenking»), May 4, a similar observance in the Netherlands

- Volkstrauertag («People’s Mourning Day»), a similar observance in Germany usually in November

- Yom Hazikaron (Israeli memorial day), the day before Independence Day (Israel), around Iyar 4

- Decoration Day (Canada), a Canadian holiday that recognizes veterans of Canada’s military which has largely been eclipsed by the similar Remembrance Day

- Memorial Day (South Korea), June 6, the day to commemorate the men and women who died while in military service during the Korean War and other significant wars or battles

- Victoria Day, a Canadian holiday on the last Monday before May 25 each year, lacks the military memorial aspects of Memorial Day but serves a similar function as marking the start of cultural summer

References[edit]

- ^ «Memorial Day». History.com.

- ^ a b «Memorial Day». United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ 36 U.S.C. § 116

- ^ Yan, Holly (May 26, 2016). «Memorial Day 2016: What you need to know». CNN. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ a b «Today in History — May 30». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Administration, National Cemetery. ««Memorial Day Order» — National Cemetery Administration». www.cem.va.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ «Memorial Day History». cem.va.gov. May 26, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Administration, National Cemetery. «Memorial Day History — National Cemetery Administration». www.cem.va.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Kickler, Sarah (May 28, 2012). «Memorial Day vs. Veterans Day». baltimoresun.com. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ «Memorial Day History». U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ Klein, Christopher. «Where Did Memorial Day Originate?». HISTORY. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ «The Center for Civil War Research». www.civilwarcenter.olemiss.edu. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Mary L’Hommedieu Gardiner (1842). «The Ladies Garland». J. Libby. p. 296. Retrieved May 31, 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ In 1817, for example, a writer in the Analectic Magazine of Philadelphia urged the decoration of patriot’s graves. E.J., «The Soldier’s Grave,» in The Analectic Magazine (1817), Vol. 10, 264.

- ^ a b «The Origins of Memorial Day» Snopes.com, May 25, 2018

- ^ Roos, Dave. «One of the Earliest Memorial Day Ceremonies Was Held by Freed African Americans». HISTORY. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Blight, David W. «Lecture: To Appomattox and Beyond: The End of the War and a Search for Meanings, Overview». Oyc.yale.edu. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

Professor Blight closes his lecture with a description of the first Memorial Day, celebrated by African Americans in Charleston, SC 1865.

- ^ David Blight, cited by Campbell Robertson, «Birthplace of Memorial Day? That Depends Where You’re From,» New York Times, May 28, 2012 – Blight quote from 2nd web page: «He has called that the first Memorial Day, as it predated most of the other contenders, though he said he has no evidence that it led to General Logan’s call for a national holiday.»

- ^ «Times-Dispatch». Perseus.tufts.edu. July 15, 1906. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Poland Jr., Charles P. The Glories Of War: Small Battle And Early Heroes Of 1861. Bloomington, IN (2006), 42.

- ^ a b c d e Bellware, Daniel (2014). The Genesis of the Memorial Day holiday in America. ISBN 9780692292259. OCLC 898066352.

- ^ «Mississippi Confederate Monument – Jackson, MS». Waymarking.com. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ a b National Park Service, «Flowers For Jennie» Retrieved February 24, 2015

- ^ Gallagher, Gary W.; Nolan, Alan T. (2000). The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253109026. Retrieved May 25, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Johnson, Kristina Dunn (2009). No Holier Spot of Ground: Confederate Monuments & Cemeteries of South Carolina. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781614232827. Retrieved May 25, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kammen, Michael (2011). Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307761408. Retrieved May 25, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ English, Tom. «A ‘complicated’ journey: The story of Logan and Memorial Day». The Southern. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Logan, Mrs. John A. (1913). Mrs. Logan’s Memoirs. p. 246. Retrieved April 7, 2014 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ «Birthplace of Memorial Day? That Depends Where You’re From». The New York Times. May 27, 2012.

- ^ a b «Memorial Day’s Roots Traced To Georgia» Michael Jones, Northwest Herald, May 23, 2015.

- ^ Brockell, Gillian (May 27, 2019). «Memorial Day’s Confederate Roots: Who Really Invented the Holiday?». The Washington Post. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Fallows, Deborah (May 23, 2014). «A Real Story of Memorial Day». The Atlantic. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Adams, Will (May 25, 2017). «Decoration Day & The Origins Of Memorial Day». RelicRecord. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ «Confederate Decoration Day Historical Marker». Hmdb.org. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ «MSU library, Ole Miss anthropologist, local historian search for Union graves». The Clarion Ledger. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ «Today in History – May 30 – Memorial Day». United States Library of Congress. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ a b University of Michigan; EBSCO Publishing (Firm) (2000). America, history and life. Clio Press. p. 190.

- ^ a b Karen L. Cox (2003). Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Universbuttse Memorial Day. ISBN 978-0813031330.

- ^ «Lincoln’s Message to Today,» Trenton (NJ) Evening Times, May 30, 1913.

- ^ Lloyd, Lewis (1941). Myths After Lincoln. New York: Press of the Readers Club. pp. 309–10.[ISBN missing]

- ^ «Sophie Keller Hall, in The Story of Our Regiment: A History of the 148th Pennsylvania Vols., ed. J.W. Muffly (Des Moines: The Kenyon Printing & Mfg. Co., 1904), quoted in editor’s note, p. 45». Civilwarcenter.olemiss.edu. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ «Boalsburg, PA, birthplace of Memorial Day». Boalsburg.com. March 26, 1997.

- ^ Muffly, J. W. (Joseph Wendel) (1904). The story of our Regiment : a history of the 148th Pennsylvania Vols. Butternut and Blue. p. 45. ISBN 0935523391. OCLC 33463683.

- ^ Flynn, Michael (2010). «Boalsburg and the Origin of Memorial Day». Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Alan Jabbour; Karen Singer Jabbour (2010). Decoration Day in the Mountains: Traditions of Cemetery Decoration in the Southern Appalachians. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8078-3397-1. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ P. Michael Jones, Daniel Bellware, and Richard Gardiner (Spring–Summer 2018). «The Emergence and Evolution of Memorial Day». Journal of America’s Military Past. 43–2 (137): 19–37. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Logan, Mrs. John A. (1913). General John Logan, quoted by his wife. Retrieved April 7, 2014 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ «A Complicated Journey: The Story of Logan and Memorial Day» Tom English, The Southern Illinoisian, May 22, 2015

- ^ Halstead, Marilyn. «Did Logan start Memorial Day? Logan museum director invites visitors to decide». thesouthern.com.

- ^ WTOP (May 25, 2018). «The forgotten history of Memorial Day». wtop.com.

- ^ Blight (2004), pp. 99–100

- ^ Cohen, Hennig; Coffin, Tristram Potter (1991). The Folklore of American holidays. p. 215. ISBN 978-0810376021 – via Gale Research.

- ^ «Barack Obama, Weekly Address» (transcript). Whitehouse.gov. May 29, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2014 – via National Archives.

- ^ «Interments in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Cemeteries» (PDF). Washington, DC: National Cemetery Administration – Department of Veterans Affairs VA-NCA-IS-1. January 2011.

After the Civil War, search and recovery teams visited hundreds of battlefields, churchyards, plantations and other locations seeking wartime interments that were made in haste. By 1870, the remains of nearly 300,000 Civil War dead were reinterred in 73 national cemeteries.

- ^ Johnson, Lyndon. «Presidential Proclamation 3727». Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ «The origin of Memorial Day: Is Waterloo’s claim to fame the result of a simple newspaper typo?»

- ^ Joan Waugh; Gary W. Gallagher (2009). Wars Within a War: Controversy and Conflict Over the American Civil War. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8078-3275-2.

- ^ Stuart McConnell (1997). Glorious Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic, 1865–1900 p. 184.ISBN 978-0807846285

- ^ Gardiner and Bellware, p. 87

- ^ Lucian Lamar Knight (1914). Memorial Day: Its True History. Retrieved May 28, 2012 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ a b c «Confederate Memorial Day in Georgia». GeorgiaInfo. University of Georgia. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ David W. Blight (2001). Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Harvard U.P. p. 265. ISBN 978-0674022096.

- ^ Nicholas W. Sacco, «The Grand Army of the Republic, the Indianapolis 500, and the Struggle for Memorial Day in Indiana, 1868–1923.» Indiana Magazine of History 111.4 (2015): 349–380, at p. 352

- ^ Samito, Christian G. (2009). Becoming American Under Fire: Irish Americans, African Americans, and the Politics of Citizenship During the Civil War Era. Cornell University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8014-4846-1. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ G. Allan Yeomans, «A Southern Segregationist Goes to Gettysburg,» Alabama Historical Quarterly (1972) 34#3 pp. 194–205.

- ^ Henry Perkins Goddard; Calvin Goddard Zon (2008). The Good Fight That Didn’t End: Henry P. Goddard’s Accounts of Civil War and Peace. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-57003-772-6.

- ^ Alan Axelrod (2007). Miracle at Belleau Wood: The Birth of the Modern U.S. Marine Corps. Globe Pequot. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-59921-025-4.

- ^ a b «Public Law 90-363». Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Sacco, p. 362

- ^ Sacco, p. 376