Полный текст книги на русском можно скачать здесь в формате DjVu. Объем 7 МБ. Если у вас на компьютере нет программы для работы с такими файлами, то бесплатно её можно установить, например, отсюда.

В сокращении Святослава Игоревича Забелина можно прочесть тут.

Ну и совсем краткий вариант — мои выдержки из сокращенного текста Святослава Забелина — ниже.

« Я рад, что эта книга может быть опубликована на русском языке, поскольку россияне самым непосредственным образом участвовали в нашем проекте с момента его начала более чем 35 лет назад. Джермен Гвишиани был одним из учредителей Римского клуба, сформулировавшего задачу и оказавшего первоначальную финансовую поддержку нашему исследованию, выполненному в Массачусетском технологическом институте в 1970-1972 гг. При содействии Моссовета Д.Гвишиани организовал и провел зимой 1970 г. в Москве научный семинар, сыгравший важную роль в первичном анализе материалов и их представлении общественности.

Сейчас выходит третье издание нашего доклада Римскому клубу. Обратите внимание на тот факт, что мы не изменили своих прогнозов. Мы только обновили данные и для подтверждения наших первоначальных выводов включили в книгу результаты многочисленных международных исследований, проведенных за прошедшее десятилетие. На основании наших исследований мы по-прежнему делаем выводы о том, что еще в первой половине текущего столетия существующие социально-экономические и политические тенденции приведут к разрушению основ индустриального общества, если не будут осуществлены значительные изменения. В 1972 году мы отводили на смену курса 50 лет, но теперь время сжалось, а политики все еще пытаются идти проторенной дорогой. Глобальные проблемы изменения климата, истощение ресурсов нефти, деградация сельскохозяйственных земель, дефицит пресной воды и их последствия уже проявились или проявятся в течение нескольких ближайших десятилетий. Еще не поздно перейти на путь устойчивого развития. Однако многие важные возможности были утрачены из-за 35-летнего отрицания очевидных фактов. :.

Деннис Медоуз,

Вена, 2 ноября 2006 года.

——

От авторов. С чего все начиналось.

Книга <Пределы роста> была результатом исследования, проведенного отделом системной динамики в Слоуновской школе менеджмента Массачусетского технологического института (МТИ) в 1970-1972 гг. Чтобы проанализировать причины и следствия роста населения и материального потребления в долговременной перспективе, исследовательская группа использовала теорию системной динамики и компьютерное моделирование. Мы ставили перед собой вопросы: К чему приведут человечество существующие тенденции — к устойчивому будущему или к глобальной катастрофе? Что можно сделать для того, чтобы создать экономику, обеспечивающую всем необходимым всех людей на планете?

Основой нашей работы стала компьютерная модель World3, в которой мы объединили статистические данные и различные теории роста.

В <Пределах роста> мы пришли к выводу о том, что воздействие на окружающую среду в масштабах земного шара (расходование природных ресурсов и выбросы загрязнений) сильно скажется на развитии мира в ХХI в. <Пределы роста> предупреждали, что человечеству придется направлять больше усилий и капитала на то, чтобы бороться с ухудшением состояния окружающей среды. Книга не уточняла, какой именно ресурс истощится первым или какой именно вид выбросов положит конец росту в тот момент, когда в борьбу с последствиями потребуется вкладывать больше средств, чем это физически возможно.

В книге <Пределы роста> мы выражали надежду на то, что будут предприняты упреждающие меры, которые позволят избежать роста нагрузки на окружающую среду и выхода за пределы самоподдержания Земли. :.

Двенадцать сценариев, приведенных в <Пределах роста>, показывают, как рост населения и потребления природных ресурсов соотносится с разными пределами. В реальной жизни пределы роста многообразны. В нашем исследовании мы сосредоточились в основном на физических пределах планеты. В каждом реально возможном сценарии модели World3 мы обнаруживали, что эти пределы рано или поздно остановят рост в ХХI веке.

В нашем исследовании не было пределов, возникших внезапно, из ниоткуда. В представленных сценариях рост населения и материального капитала постепенно вынуждает человечество направлять все больше и больше капитала на решение проблем, которые вызваны его же воздействием на среду. Со временем потребуется тратить столько, что поддерживать дальнейший промышленный рост станет невозможно. Когда промышленность приходит в упадок, общество не может поддерживать рост и в других секторах экономики: в производстве продуктов питания, сфере обслуживания и иных областях потребления. Когда останавливается рост в этих секторах, рост населения также прекращается.

Прекращение роста может принимать разные формы. Оно может произойти катастрофически быстро: неконтролируемое уменьшение численности населения одновременно с резким снижением уровня жизни. Сценарии модели World3 предсказывают такую катастрофу не по одной, а по целому ряду причин. Окончание роста может выглядеть и как плавный переход, при котором воздействие человека на окружающую среду приводится в соответствие с поддерживающей способностью планеты. Задавая принципиальные изменения в деятельности человека, мы можем заставить модель World3 создать такой сценарий, в котором окончание роста будет сопровождаться длительным периодом относительно высокого благосостояния.

Конец роста.

Прекращение роста, в какой бы форме оно ни происходило, в 1972 году казалось нам делом отдаленного будущего. Все сценарии модели World3 из книги <Пределы роста> предсказывали продолжение роста населения и капиталов и в 2000 г., и долгое время после него. Даже в самом пессимистическом сценарии материальный уровень жизни продолжал расти до 2015 г. В книге предполагалось, что рост остановится примерно через 50 лет после публикации книги — вполне достаточный срок для того, чтобы хорошо подумать, сделать выбор и принять правильные меры даже в масштабах всего земного шара.

Создавая книгу <Пределы роста>, мы очень надеялись, что здравое размышление позволит обществу сделать верные шаги и снизить вероятность глобальной катастрофы. Мировой кризис — малоприятная перспектива. Упадок экономики и резкое уменьшение численности населения до уровней, которые способна выдержать окружающая среда, обязательно будут сопровождаться ухудшением здоровья людей, конфликтами и столкновениями, разрушением экосистем и вопиющим социальным неравенством.

Стоит лишний раз повторить, что рост совсем не обязательно ведет к глобальной катастрофе. Кризис наступает только в том случае, если рост привел к выходу за пределы: запросы настолько велики, что ресурсы планеты истощаются, и тогда она уже не в состоянии обеспечить самоподдержание.

В 1972 году казалось, что население и мировая экономика с большим запасом вписываются в пределы емкости планеты. Мы считали, что еще достаточно времени для безопасного продолжения роста и одновременного анализа долгосрочных перспектив. Наверное, в 1972 г. так оно и было, но к 1992 году все изменилось.

1992 год: За пределами роста

В 1992 году мы обновили исследование 20-летней давности и опубликовали результаты в книге <За пределами роста>. Книга <За пределами роста> укрепила первоначальные опасения, и в 1992 г. мы убедились, что два прошедших десятилетия только подтвердили выводы, сделанные двадцать лет назад. Однако исследование 1992 года показало и кое-что новое: мы обнаружили, что человечество уже вышло за пределы самоподдержания Земли.

Даже в начале 90-х гг. было ясно, что человечество идет туда, где самоподдержание уже невозможно. Например, было установлено, что влажные тропические леса вырубаются в недопустимых масштабах; появились заявления о том, что общемировое производство зерна больше не в состоянии поддеживать рост населения; укрепились опасения насчет глобального потепления климата; к этому времени стратосферные озоновые дыры воспринимались со всей серьезностью : Однако для большинства людей на планете все это по-прежнему не значило, что человечество вышло за пределы самоподдержания окружающей среды. Мы протестовали.

Но теперь нам известно, что цели, поставленные в Рио, так и не были достигнуты. Конференция <Рио + 10> в Йоханнесбурге в 2002 году принесла еще меньше пользы: вся работа была практически парализована дискуссиями на идеологические и экономические темы, которые велись в узких национальных, корпоративных, а то и просто в личных интересах.

Последние 10 лет позволили нам накопить данные, которые укрепили наш вывод о том, что мир уже вышел за пределы. Сейчас совершенно ясно, что максимум производства зерна на душу населения пройден в середине 80-х.

Ожидания существенного роста морского вылова рыбы не оправдались. Природные катаклизмы с каждым годом обходятся миру все дороже и дороже, а борьба за пресную воду и ископаемые виды топлива становится все жестче, подчас приобретая формы прямых столкновений. Соединенные Штаты и другие ведущие страны продолжают увеличивать выбросы парниковых газов, хотя метеорологические данные свидетельствуют о том, что климат меняется, и ученые уже пришли к единому мнению о том, что это прямое следствие человеческой деятельности.

К сожалению, нагрузка со стороны человека на окружающую среду продолжает расти, несмотря на развитие технологий и усилия общественных организаций. Положение осложняется тем, что человечество уже вышло за пределы и находится в неустойчивой области. Однако понимание этой проблемы во всем мире удручающе слабое. Чтобы снизить воздействие на окружающую среду и вернуться к допустимому уровню, необходимо изменить личностные и общественные ценности, а чтобы добиться у политиков поддержки в этой области, времени нужно очень много.

По этим причинам сегодня мы оцениваем перспективы развития мира гораздо пессимистичнее, чем в 1972 г. Грустно, но факт: человечество впустую потратило целых 30 лет, обсуждая не те проблемы, что нужны, и принимая слабые, нерешительные меры по защите окружающей среды. У нас нет других 30 лет.

Мы обрисовываем альтернативные сценарии, с которыми может встретиться человечество: Тем не менее из прошедших 30 лет можно извлечь полезные уроки.

Тем, кто больше уважает цифры, мы можем сообщить: итоговые сценарии модели World3 оказались на удивление точными — прошедшие 30 лет подтвердили это. Численность населения в 2000 г — порядка 6 миллиардов человек, в сравнении с 3,9 миллиарда в 1972 г. — оказалась именно такой, какой мы ее рассчитывали по модели World3 в 1972 г. Больше того, сценарий, показывавший рост мирового производства продовольствия (с 1,8 млрд тонн в год в зерновом эквиваленте в 1972 г. до 3 млрд тонн в 2000 г.) практически совпали с реальными цифрами. :.

Самые важные выводы — о вероятности глобальной катастрофы — вовсе не основаны на слепой вере в графики, нарисованные моделью. Они вытекают из простого понимания динамики поведения глобальной системы, которая определяется тремя ключевыми факторами:

— существованием пределов;

— постоянным стремлением к росту;

— запаздыванием между приближением к пределу и реакцией общества на это.

Любая система, которой свойственны эти три фактора, рано или поздно выйдет за пределы и разрушится. :.

Поскольку причинно-следственные связи в реальном мире никто не отменял, вас не должно удивлять, что реальный мир идет по пути, который был описан в сценариях (С.З. — в самых худших из возможных!!!) <Пределов роста>.

Мы уверены и в том, что если не произвести серьезную коррекцию в самое ближайшее время, то крах в той или иной форме будет неизбежен. И наступит он еще при жизни сегодняшнего поколения.

Это заявление чудовищно. Как же мы пришли к нему? За прошедшие 30 лет мы и многие наши коллеги работали над анализом долговременных причин и следствий роста численности населения и вызванной этим экологической нагрузки. Мы использовали четыре разных подхода, можно сказать, четыре увеличивающих прибора разной кратности, позволяющих увидеть мир с разных точек зрения, подобно тому как линзы микроскопа и телескопа позволяют увидеть разные картины. Три из них широко известны, их легко описать: (1) стандартная научно-экономическая теория глобальной системы; (2) статистические данные по окружающей среде и мировым ресурсам; (3) компьютерная модель, позволяющая обобщить всю информацию и сделать выводы. Большая часть этой книги построена на этих трех подходах: мы рассказываем, как мы применили их, и что это нам дало.

Четвертый подход — то наше мировоззрение, наша личная позиция, наши ценности — основа нашего взгляда на окружающую действительность.

Самая важная составляющая нашего восприятия мира (что, наверное, меньше всего разделяется другими людьми) — это взгляд на мир как на систему.

Как и всякая точка зрения — например, вершина холма — системный подход позволяет человеку увидеть то, что с других точек зрения увидеть невозможно, но при этом скрыть от взгляда другие вещи. Он обращает внимание на динамические системы — наборы взаимосвязанных материальных и нематериальных элементов, меняющихся со временем. Он позволяет увидеть мир как совокупность моделей поведения, таких как рост, спад, колебания, выход за пределы. Он позволяет сосредоточиться не на элементах, а на связях между ними.

Люди поддерживают идеи роста, поскольку полагают, что это приведет к повышению их благосостояния. Правительственные чиновники уверены в том, что рост — универсальное средство буквально от любых проблем.

Многие полагают, что рост необходим, чтобы иметь достаточные ресурсы для защиты окружающей среды. Правительства и руководители корпораций делают все возможное и невозможное для того, чтобы рост продолжался.

Все это приводит к тому, что рост воспринимается как нечто позитивное, желаемое.

Таковы психологические и организационные движущие силы роста. Есть еще так называемые структурные причины, кроющиеся внутри связей между элементами демографо-экономической системы.

Рост может решить одни проблемы, но при этом создает другие, поскольку у него есть пределы. Возможности Земли не безграничны. Рост любого материального показателя, будь то численность населения, число автомобилей, домов и заводов, не может продолжаться бесконечно.

Физические пределы роста — это пределы способности планетарных источников предоставлять нам потоки сырья и энергии, а стоков — поглощать загрязнения и отходы.

Плохая новость состоит в том, что многие важнейшие источники истощаются и деградируют, а большинство стоков уже переполнено.

ПОТОКИ, ИСПОЛЬЗУЕМЫЕ ЭКОНОМИЧЕСКОЙ СИСТЕМОЙ В НАСТОЯЩЕЕ ВРЕМЯ, НЕВОЗМОЖНО ПОДДЕРЖИВАТЬ В ТАКИХ МАСШТАБАХ ПРОДОЛЖИТЕЛЬНОЕ ВРЕМЯ.

Хорошая новость заключается в том, что СУЩЕСТВУЮЩИЕ ТЕМПЫ ИСПОЛЬЗОВАНИЯ РЕСУРСОВ ВОВСЕ НЕ ЯВЛЯЮТСЯ НЕОБХОДИМЫМИ ДЛЯ ПОДДЕРЖАНИЯ ДОСТОЙНОГО УРОВНЯ ЖИЗНИ ВСЕХ ЛЮДЕЙ НА ПЛАНЕТЕ.

Варианты возможного будущего включают в себя множество разных путей. Это может быть резкий спад и катастрофа, но это может быть и постепенный переход к самоподдержанию. Среди вариантов нет только одного: бесконечного роста в физически ограниченном пространстве. : Единственный реально возможный путь — привести потоки, поддерживающие существование человека, в соответствие с допустимыми уровнями. Либо мы сделаем это сами, сознательно, с помощью технических и организационных мер, либо природа сделает это за нас — наступит нехватка продовольствия, сырья, энергии или среда станет неблагоприятной для проживания.

Множество людей признают, что на локальном уровне экологические нагрузки превышают локальные же пределы устойчивости. Город Джакарта выбрасывает в воздушную среду больше загрязнений, чем могут перенести человеческие легкие. Леса на Филиппинах сведены практически полностью. Почвы на Гаити истощены до такой степени, что под ними проглядывают скальные породы. Рыболовецкие артели на Ньюфаундленде распущены, потому что им нечего больше ловить.

И все равно сейчас общие проблемы выхода за пределы обсуждаются недостаточно широко. Нет давления, которое заставило бы в срочном порядке принимать технические меры по повышению эффективности. Практически нет готовности и желания делать что-нибудь с причинами роста населения и капитала. : Однако сегодня, на пороге нового тысячелетия, отрицать очевидное невозможно. Выход за пределы — это ужасная реальность, и игнорировать ее последствия непростительно.

Причины, по которым о проблеме выхода за пределы избегают говорить вслух, понять несложно — они чисто политические. Любое упоминание о снижении роста тут же приводит к наболевшей проблеме распределения ресурсов и к поиску ответственных за создавшееся положение.

Хотя всем хочется точно знать, что нас ждет в будущем, тем не менее, когда кто-то предлагает модель для изучения этого будущего, это часто вызывает непонимание и чувство разочарования. Мы столкнулись с этим сразу же после опубликования первого издания этой книги более 30 лет назад. «

Модель World3: два возможных сценария

В модели мира WorldЗ основная цель — рост. Численность населения в модели перестанет расти только тогда, когда оно станет очень богатым. Экономика в модели перестанет расти только тогда, когда ее вынудят к этому пределы. Ресурсы в модели расходуются и истощаются из-за чрезмерного использования. Контуры обратной связи, которые соединяют элементы системы, содержат существенные запаздывания, а физические процессы обладают большой инерцией. Поэтому вас не должно удивлять, что самым распространенным сценарием поведения системы будет выход за пределы и катастрофа.

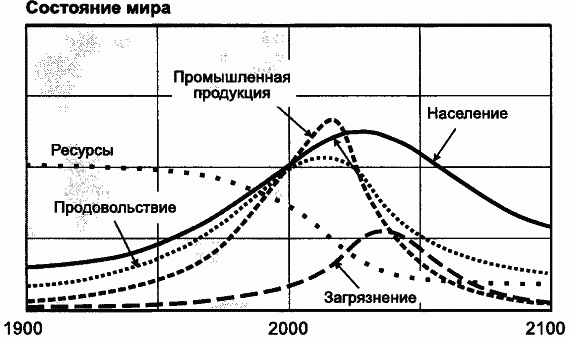

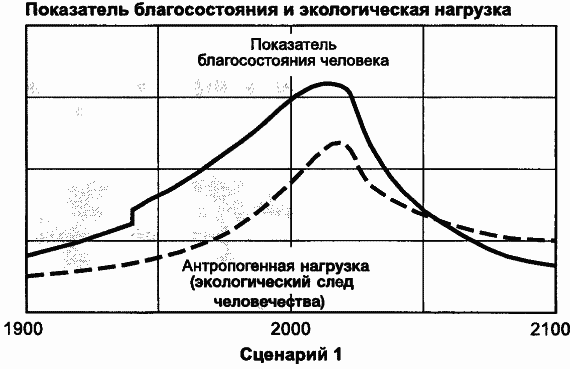

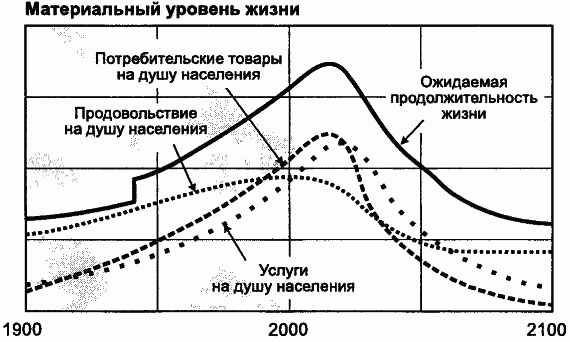

На рис. 4.11, в Сценарии 1, показано «базовое» поведение модели WorldЗ с настройками, которые мы полагаем наиболее реалистичными — они с максимальным правдоподобием описывают состояние мира в конце XX в., без маловероятных или заведомо нереальных предположений об уровнях развития технологии или политических усилиях. В 1972 г. мы называли этот сценарий «стандартным». Но при этом мы вовсе не утверждали, что это самый вероятный вариант развития событий, да и теперь мы не преподносим его как предсказание будущего. Это просто стартовая точка, ориентир для последующего сравнения. Однако многие читатели почему-то воспринимали «стандартный» сценарий как ключевой, более важный, чем все остальные. Чтобы этого не повторялось в новом издании книги, мы отказались от названия «стандартный» сценарий и стали называть его просто «отправной точкой». И теперь по номерам упорядочены все сценарии, а не часть. Этому сценарию достался номер 1.

В Сценарии 1 общество вдет привычным путем, без серьезных политических изменений, до тех пор, пока это возможно. Здесь прослеживаются очертания хорошо нам известной истории XX в. Производство продовольствия, промышленной продукции и социальных услуг возрастает в ответ на явные запросы, при условии, что в это вкладывается капитал. Никакие экстраординарные усилия к тому, чтобы уменьшить выбросы загрязнений, сберечь ресурсы или защитить почвы от деградации, не предпринимаются, если только это не ведет к немедленному получению прибыли. Моделируемый мир стремится провести все население планеты через демографический переход и достичь процветания за счет индустриализации экономики. В Сценарии 1 по мере роста сектора услуг в мире повсеместно развиваются здравоохранение и программы контроля рождаемости. В сельском хозяйстве в процессе его развития используется все больше промышленной продукции, поэтому урожайность

Рис. 4.11. Сценарий 1: «отправная точка»

Мировое общество идет привычным путем без каких-либо существенных политических изменений в политике, характерной для конца XX в. Численность населения и производство растут до тех пор, пока этому не кладет конец увеличивающаяся нехватка невозобновимых ресурсов. Для поддержания потоков ресурсов требуется все больше и больше финансовых вложений. В конце концов нехватка инвестиций в других секторах экономики приводит к уменьшению производства промышленных товаров и услуг. Вследствие этого приходят в упадок производство продовольствия и здравоохранение, что снижает ожидаемую продолжительность жизни и увеличивает коэффициент смертности.

растет. Промышленный сектор непрерывно развивается, производство промышленной продукции растет, выбросы загрязнений увеличиваются, требуется все больше невозобновимых ресурсов.

Численность населения в Сценарии 1 возрастает с 1,6 млрд чел. в 1900 расчетном году до 6 млрд в 2000 г., и превышает 7 млрд в 2030 г. Суммарное производство промышленной продукции увеличивается с 1900 по 2000 г. почти в 30 раз, а затем еще на 10 % к 2020 г. В период между 1900 и 2000 гг. расходуется не более 30 % запасов невозобновимых ресурсов планеты, к 2000 г. более 70 % ресурсов еще сохраняются невостребованными. Уровень загрязнения в моделируемом 2000 г. только-только начал существенно расти, превышая уровень 1990 г. на 50 %. Потребление промышленных товаров на душу населения в 2000 г. на 15 % больше, чем в 1990 г., и примерно в 8 раз больше, чем было в 1900 г.[151].

Если закрыть рукой правую половину графиков Сценария 1, чтобы были видны кривые только до 2000 г., то смоделированный мир выглядит вполне успешным и счастливым. Ожидаемая продолжительность жизни растет, производство услуг и товаров на душу населения увеличивается, суммарное производство продовольствия и промышленной продукции тоже растет. Средний уровень благосостояния человека постоянно увеличивается. Лишь пара тревожных сигналов просматривается на горизонте: растут уровень загрязнения и экологическая нагрузка. Производство продовольствия на душу населения прибавляться перестало. Но в целом система продолжает демонстрировать рост, и нет почти никаких указаний на то, что впереди ее ждут грандиозные потрясения.

Затем неожиданно в первые несколько десятилетий XXI в. экономический рост останавливается, начинается резкий спад. Резкое прекращение прироста, имевшего место так долго, вызвано быстро повышающимися ценами на невозобновимые ресурсы. Такое положение отражается на различных секторах экономики в виде резко падающих инвестиций. Процесс можно проследить подробно.

В расчетном 2000 г. еще остается столько невозобновимых ресурсов, что этого должно хватить на 60 лет, если темпы потребления будут такими же, как в 2000 г. Пока что никакие пределы по ресурсам не проявились. Однако в 2020 г. остающихся ресурсов хватит уже только на 30 лет. Почему пределы так резко приблизились? Потому, что потребление ресурсов выросло из-за увеличившегося населения и промышленного капитала, при этом остающиеся запасы постоянно уменьшались. За период между 2000 и 2020 гг. население увеличилось на 20 %, а промышленное производство — на 30 %. За два этих десятилетия в Сценарии 1 и то, и другое израсходовали практически столько же невозобновимых ресурсов, сколько вся мировая экономика за все предыдущее столетие! Естественно, теперь для мира в его непрестанных усилиях продолжить рост нужно все больше капитала для поиска, добычи и переработки остатков невозобновимых ресурсов.

По мере того, как в Сценарии 1 добыть невозобновимые ресурсы становится все труднее и труднее, на это из других секторов экономики отвлекается все больше и больше капитала. Для сельского хозяйства и промышленности остается меньше промышленной продукции. В конце концов примерно в 2020 г. инвестиции в промышленную сферу уже не могут компенсировать выбытие основных средств. (Это физические вложения и амортизация; другими словами, физическое оборудование изнашивается, выходит из строя и устаревает — речь идет не о денежной амортизации по бухгалтерским книгам.) В результате промышленность переживает резкий спад, который в этой ситуации избежать невозможно, поскольку экономика не может перестать вкладывать капитал в ресурсодобывающие отрасли. И даже если бы могла, тогда дефицит сырья и топлива ограничили бы промышленное производство еще быстрее.

Поскольку на амортизацию и поддержание оборудования в рабочем состоянии средств недостаточно, промышленное производство начинает падать, а следовательно, уменьшается и количество промышленной продукции, нужной для поддержания роста капитала и направления в другие сектора экономики. В конце концов уменьшение промышленного производства приводит к спаду в аграрном секторе и в сфере услуг, которые так или иначе зависят от поступлений промышленной продукции. На сельском хозяйстве в Сценарии 1 это отражается особенно сильно, поскольку продуктивность земли и без того пострадала от чрезмерного использования (даже в период до 2000 г.). Производство продовольствия поддерживалось на высоком уровне только за счет того, что деградация земель компенсировалась широким использованием химических удобрений, пестицидов, оросительного оборудования, а все это дает промышленность. Чем дальше, тем хуже: население продолжает расти из-за демографической инерции, в силу особенностей возрастной структуры населения и традиций при выборе желаемого размера семьи. Наконец, примерно в 2030 г. численность населения проходит максимум и начинает уменьшаться, так как из-за нехватки продовольствия и услуг здравоохранения увеличивается коэффициент смертности. Средняя продолжительность жизни, составлявшая в 2010 г. 80 лет, начинает снижаться.

Этот сценарий иллюстрирует «кризис невозобновимых ресурсов». Он — не предсказание и не предназначен для того, чтобы точно прогнозировать значения тех или иных переменных в модели либо оценивать время наступления тех или иных событий. Мы вовсе не утверждаем, что это наиболее вероятное будущее «реального мира». Чуть дальше мы покажем, что есть другая возможность будущего, а в гл. 6 и 7 обрисуем много других возможностей. В том, что касается Сценария 1, мы можем утверждать только следующее: он дает общую схему поведения системы, если политика, определяющая экономический рост и увеличение численности населения, в будущем останется такой же, как и в конце XX в., если технологии и цены будут изменяться примерно также и если заданные с некоторой неопределенностью численные параметры модели окажутся близкими к истине.

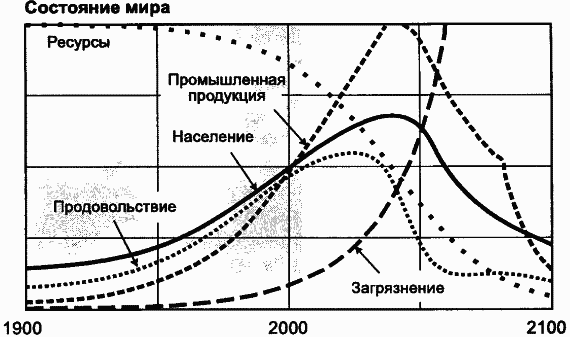

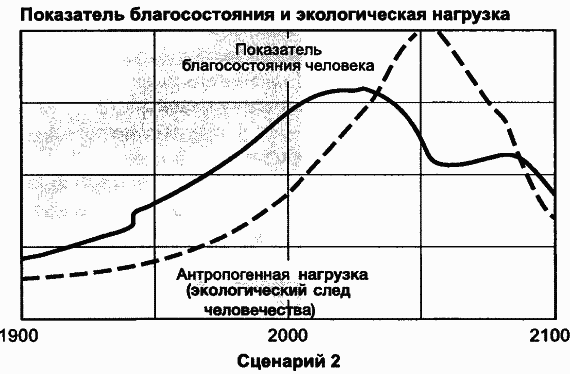

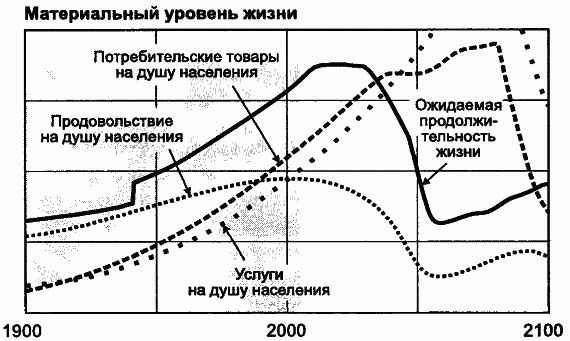

Что, если наши предположения неверны, а численные параметры заданы неточно? Чем будет отличаться поведение системы, если, например, запасы невозобновимых ресурсов в недрах планеты окажутся вдвое больше, чем мы задали в Сценарии 1? Этот вариант показан в Сценарии 2 (рис. 4.12).

Как вы можете заметить, здесь истощение ресурсов наступает существенно позже, чем в Сценарии 1, и рост продолжается дольше, 20 лет дополнительно, и этого вполне достаточно для того, чтобы в промышленном производстве и потреблении ресурсов произошло очередное удвоение. Численность населения тоже нарастает дольше, превышая 8 млрд чел. к моменту достижения максимума в расчетном 2040 г. Но несмотря на это, общее поведение модели по-прежнему указывает на выход за пределы и на катастрофу. Только основной причиной катастрофы на этот раз становится сильнейшее загрязнение окружающей среды.

Высокие уровни промышленного производства приводят к чрезвычайному усилению загрязнения; в Сценарии 2 уровень загрязнения достигает максимума на 50 лет позже, чем в Сценарии 1, и превышает его примерно в 5 раз. Такое сильное загрязнение частично объясняется большими объемами выбросов, частично — разрушением механизмов самоочищения окружающей среды, в результате чего разложение выбросов замедляется. В 2090 г., в самый тяжелый момент, среднее время жизни загрязнителей в среде более чем втрое превышает этот показатель в 2000 г. Экологическая нагрузка растет также в результате использования непомерных количеств химических удобрений, пестицидов и других сельскохозяйственных химикатов.

Загрязнение очень сильно влияет на продуктивности земель, она в Сценарии 2 в первой половине XXI в. уменьшается до очень низкого уровня. Даже увеличение инвестиций в восстановление земель, направленное на борьбу с утратой продуктивности, не помогает предотвратить

Рис. 4.12. Сценарий 2, больше имеющихся в изобилии невозобновимых ресурсов

Если в системе вдвое больше невозобновимых ресурсов, чем мы предположили в Сценарии 1, и если разработки в ресурсодобывающих технологиях позволят отодвинуть момент, когда цены на добычу начнут расти, то промышленность сможет развиваться дополнительно 20 лет. Численность населения достигнет максимального значения около 8 млрд чел. в 2040 г., при этом уровень потребления будет гораздо выше. Однако уровень загрязнения станет огромным (кривая даже выходит за пределы диаграммы), что приведет к уменьшению урожайности и потребует огромных инвестиций в сельское хозяйство. В конце концов численность населения падает, поскольку продовольствия недостаточно, а высокий уровень загрязнения оказывает негативное воздействие на здоровье людей.

снижение урожайности и производства продовольствия: после 2030 г. падеже происходит очень резко. Из-за этого растет смертность. В тщетной попытке справиться с голодом в сельскохозяйственный сектор направляются еще большие капиталы, и в результате из-за отвлечения средств от реинвестирования прекращается рост и в промышленном секторе.

Сценарий 2 иллюстрирует «глобальный кризис загрязнения окружающей среды». В первой половине XXI в. уровень загрязнения увеличивается настолько, что это влияет на продуктивность земель. В «реальном мире» это может произойти из-за загрязнения почвы тяжелыми металлами или стойкими химическими соединениями; вследствие изменения климата и связанных с ним мутаций растительных сообществ, происходящих быстрее, чем фермеры могут к этому приспособиться; в результате увеличения уровня ультрафиолетового излучения, достигающего Земли, из-за истощения озонового слоя. Продуктивность земель лишь слегка уменьшается в период с 1970 по 2000 гг., падает на 20 % в период с 2000 по 2030 гг., а к 2060 г. составляет лишь малую толику уровня продуктивности 2000 г. В то же самое время эрозия почв очень велика. Суммарное производство продовольствия начинает падать в 2030 г., вынуждая экономику направлять основные инвестиции в сельскохозяйственный сектор, чтобы поддержать производство продуктов питания на достаточном уровне. Однако разрушительный эффект от загрязнения так силен, что производство продовольствия уже никогда не достигнет высокого уровня. Во второй половине XXI в. на фоне нехватки продовольствия загрязнение достигает таких значений, что из-за этого средняя ожидаемая продолжительность жизни сильно уменьшается. Антропогенная нагрузка на окружающую среду огромна, пока наступившая катастрофа не уменьшит ее до значений, характерных для прошлого столетия.

Какой из сценариев более вероятен, Сценарий 1 или Сценарий 2? Если бы мы попытались ответить на этот вопрос на основе научных данных, все упиралось бы в «истинные» неразведанные запасы невозобновимых ресурсов на планете. Однако у нас таких истинных данных нет, да и не может быть. В любом случае в модели необходимо проверить влияние многих других параметров, заданных с допусками, а также исследовать, к чему приведут различные технологические и политические изменения. К ним мы вернемся в гл. 6 и 7. Все, что к этому моменту позволила нам узнать модель World3 — это, что моделируемая система склонна к выходу за пределы с катастрофическими последствиями. На самом деле в тех тысячах расчетов, что мы провели за все эти годы, выход за пределы и катастрофа были самыми частыми результатами. Но это не значит, что они неизбежны. Причины такого поведения читателям, наверное, на данный момент уже понятны.

капитала на то, чтобы бороться с ухудшением состояния окружающей среды. Возможно, настолько больше, что в один прекрасный день XXI в. это приведет к снижению уровня жизни. Книга не уточняла, какой именно ресурс истощится первым или какой именно вид выбросов положит конец росту в тот момент, когда в борьбу с последствиями потребуется вкладывать больше средств, чем это физически возможно. В большой и сложной системе, учитывающей численность населения, экологические и экономические факторы, просто невозможно давать детальные прогнозы, не погрешив против научного подхода.

В книге «Пределы роста» мы выражали надежду на то, что будут предприняты упреждающие меры, которые позволят избежать роста нагрузки на окружающую среду и выхода за пределы самоподдержания Земли. Это должны быть серьезные, социально направленные меры, основанные на существенных изменениях в технологии, культуре и политике. Хотя глобальная проблематика была отражена со всей серьезностью, в книге мы выражали и надежду на лучшее. Снова и снова мы заостряли внимание на том, что если вовремя принять меры, то каждый из нас может значительно уменьшить вред, наносимый среде из-за приближения или даже превышения глобальных экологических пределов.

Двенадцать сценариев, приведенных в «Пределах роста», показывают, как рост населения и потребления природных ресурсов соотносится с разными пределами. В реальной жизни пределы роста многообразны. В нашем исследовании мы сосредоточились в основном на физических пределах планеты: исчерпаемых природных ресурсах и ограниченной способности Земли поглощать промышленные и сельскохозяйственные загрязнения. В каждом реально возможном сценарии модели World3 мы обнаруживали, что эти пределы рано или поздно остановят рост в XXI в.

В нашем исследовании не было пределов, возникших внезапно, из ниоткуда. В представленных сценариях рост населения и материального капитала постепенно вынуждает человечество направлять все больше и больше капитала на решение проблем, которые вызваны его же воздействием на среду. Со временем потребуется тратить столько, что поддерживать дальнейший промышленный рост станет невозможно. Когда промышленность приходит в упадок, общество не может поддерживать рост и в других секторах экономики: в производстве продуктов питания, сфере обслуживания и иных областях потребления. Когда останавливается рост в этих секторах, рост населения также прекращается.

Прекращение роста может принимать разные формы. Оно может произойти катастрофически быстро: неконтролируемое уменьшение численности населения одновременно с резким снижением уровня жизни. Сценарии модели World3 предсказывают такую катастрофу не по одной, а по целому ряду причин. Окончание роста может выглядеть и как плавный переход, при котором воздействие человека на окружающую среду приводится в соответствие с поддерживающей способностью планеты. Задавая принципиальные изменения в деятельности человека, мы можем заставить модель World3 создать такой сценарий, в котором окончание роста будет сопровождаться длительным периодом относительно высокого благосостояния.

Прекращение роста, в какой бы форме оно ни происходило, в 1972 г. казалось нам делом отдаленного будущего. Все сценарии модели World3 из книги «Пределы роста» предсказывали продолжение роста населения и капиталов и в 2000 г., и долгое время после него. Даже в самом пессимистичном сценарии материальный уровень жизни продолжал расти до 2015 г. В книге предполагалось, что рост остановится примерно через 50 лет после публикации книги — вполне достаточный срок для того, чтобы хорошо подумать, сделать выбор и принять правильные меры даже в масштабах всего земного шара.

Создавая книгу «Пределы роста», мы очень надеялись, что здравое размышление позволит обществу сделать верные шаги и снизить вероятность глобальной катастрофы. Мировой кризис — малоприятная перспектива. Упадок экономики и резкое уменьшение численности населения до уровней, которые способна выдержать окружающая среда, обязательно будут сопровождаться ухудшением здоровья людей, конфликтами и столкновениями, разрушением экосистем и вопиющим социальным неравенством. Неконтролируемое уменьшение численности населения будет следствием резкого роста смертности и соответствующего снижения потребления. Вовремя принятые меры позволили бы избежать неконтролируемого упадка. Если с помощью целенаправленных усилий ограничить запросы человечества до уровня, приемлемого для планеты, тогда с последствиями выхода за пределы можно справиться. Необходимо постепенно снизить рождаемость, обеспечить более справедливое распределение материальных благ и за счет этого уменьшить нагрузку на окружающую среду до приемлемого уровня.

Стоит лишний раз повторить, что рост совсем не обязательно ведет к глобальной катастрофе. Кризис наступает только в том случае, если рост привел к выходу за пределы: запросы настолько велики, что ресурсы планеты истощаются, и тогда она уже не в состоянии обеспечить самоподдержание. В 1972 г. казалось, что население и мировая экономика с большим запасом вписываются в пределы емкости планеты. Мы считали, что еще достаточно времени для безопасного продолжения роста и одновременного анализа долгосрочных перспектив. Наверное, в 1972 г. так оно и было, но к 1992 г. все изменилось.

1992 год: За пределами роста

В 1992 г. мы обновили исследование 20-летней давности и опубликовали результаты в книге «За пределами роста». Мы проанализировали развитие мира в период 1970–1990 гг. и внесли эту информацию в обновленную модель World3. Книга «За пределами роста» укрепила первоначальные опасения, в 1992 г. мы убедились, что два прошедших десятилетия только подтвердили выводы, сделанные двадцать лет назад. Однако исследование 1992 г. показало и кое-что новое: мы обнаружили, что человечество уже вышло за пределы самоподдержания Земли. Это было настолько важно, что мы вынесли этот факт в название книги.

Даже в начале 90-х гг. было ясно, что человечество идет туда, где самоподдержание уже невозможно. Например, было установлено, что влажные тропические леса вырубают в недопустимых масштабах; появились заявления о том, что общемировое производство зерна больше не в состоянии поддерживать рост населения; укрепились опасения насчет глобального потепления климата; к этому времени стратосферные озоновые дыры воспринимались со всей серьезностью… Однако для большинства людей на планете все это по-прежнему не означало, что человечество вышло за пределы самоподдержания окружающей среды. Мы протестовали против такой точки зрения. В нашем обзоре начала 90-х гг. мы заявляли: выход за пределы больше нельзя игнорировать, это уже свершившийся факт. Его необходимо признать, чтобы решить главную задачу: вернуть мир в область самоподдержания. Несмотря на серьезность положения, книга «За пределами роста» придерживалась оптимистической точки зрения, в большинстве сценариев показывая, что последствия от выхода за пределы поправимы, для этого надо лишь вести продуманную мировую политику и пойти на определенные изменения в технологии, управлении, общественной жизни и личностных устремлениях.

Книга «За пределами роста» увидела свет в 1992 г. В тот же год в Рио-де-Жанейро проходила встреча на высшем уровне по вопросам развития и окружающей среды. Сам факт такой встречи, казалось бы, свидетельствовал о том, что мировое сообщество наконец-то решило серьезно отнестись к экологическим проблемам. Но теперь нам известно, что цели, поставленные в Рио, так и не были достигнуты. Конференция «Рио +10» в Йоханнесбурге в 2002 г. принесла еще меньше пользы: вся работа была практически парализована дискуссиями на идеологические и экономические темы, которые велись в узких национальных, корпоративных, а то и просто в личных интересах[4] .

Продолжение, начало в предыдущих 19 постах (с)

«Читайте первоисточники» (совет моей жены преподавателя студентам)

Когда я открывал эту книгу, меня больше всего интересовал вопрос: насколько совпали прогнозы «базового» сценария модели World3 1972 года на следующие, БУДУЩИЕ на тот момент 30 лет (с 1970 по 2000 гг.) с реальными изменениями системы «население – капитал» за этот период? Ведь в 2002 году эти изменения стали уже реальным, статистическим фактом.

Далее цитирую «Пределы роста. 30 лет спустя», ИКЦ Академкнига, 2008:

«Тем, кто больше уважает цифры, мы можем сообщить: итоговые сценарии модели World3 оказались на удивление точными – прошедшие 30 лет подтвердили это. Численность населения в 2000 г. – порядка 6 млрд чел. В сравнении с 3,9 млрд в 1972 г. – оказалась именно такой, какой мы рассчитали ее по модели World3 в 1972 г. Больше того, сценарий, показывавший рост мирового производства продовольствия (с 1,8 млрд т в год в зерновом эквиваленте в 1972 г. до 3 млрд т в 2000 г.), практически совпал с реальными цифрами».

Дальнейшее добавляю уже от себя.

Соответственно вышесказанному – точным оказался и прогноз производства продовольствия на душу населения.

Прогнозируемый в 1972 г. расчет экспоненциального загрязнения атмосферы CO2 на 1987 г. – примерно 347 частей на миллион – через 17 лет вполне совпал с реальностью. В 1987 г. содержание СО2 с атмосфере составило 348 частей на миллион.

Чтобы оценить, насколько соответствует прогнозу 1972 г реальное состояния дел в 2000 г. для других ключевых показателей системы «население – капитал», я наивно вооружился прозрачной миллиметровой линейкой и увеличительным стеклом. И, насколько смог тщательно, промерил соответствующие части графиков на картинках «базовых» сценариев, полученных в 1972 г. и в 2002 г.

Так вот, в «базовом» сценарии 1972 г. модель World3 прогнозировала расход невозобновимых ресурсов к 2000 г. на уровне 30% от запасов 1900 г. Реальный расход по состоянию на 2000 г. оказался в районе 28%, т.е. практически совпал с прогнозом модели World3, данным в далеком 1972 году.

Производство потребительских товаров на душу населения в 2000 г. оказалось примерно всего лишь на 6% меньше, чем это прогнозировалось в «базовом» сценарии 1972 г. А производство услуг на душу населения – примерно на 16% больше, чем по прогнозу 1972 г.

В сумме это дает довольно небольшое – в районе 10-15% – отклонение от прогноза производства в целом товаров и услуг на душу населения на период с 1972 по 2000 г..

Т.е. опять же налицо достаточно высокая степень точности для столь продолжительного отрезка будущего, как 30 лет, в условиях стремительного развития человечества.

Напомню, за это время в мире произошли грандиозные, революционные перемены, которые в 1972 г. мало кто мог предвидеть. За эти 30 лет исчез могучий Советский Союз и социалистический лагерь, охватывавший чуть ли не половину планеты. Произошла настоящая революция в компьютерных технологиях и осуществился переход к «информационному миру». Появился Интернет!

Но, несмотря на все эти грандиозные, казалось бы, перемены, прогноз базовых показателей системы жизнеобеспечения человечества, данный в далеком 1972 г. с помощью модели World3, оказался в 2002 г. – В БУДУЩЕМ, СПУСТЯ 30 ЛЕТ – на удивление точным!

Теперь Вы можете еще раз вернуться к той самой картинке «базового», «стандартного», наиболее реалистичного сценария в постах «Пределы роста 1,2 и 3». И посмотреть на нее уже другими глазами. Посмотреть на нее, зная, что на этой картинке дан практически точный прогноз изменений в будущем основных показателей системы «население – капитал» как минимум на период в 30 лет, с 1970 по 2000 год.

И еще раз взглянуть на бледно голубую вертикальную черту, обозначающую 2010-й год. Теперь уже зная, что модель World3 прогнозирует будущее достаточно точно…

Продолжение следует

Пределы роста. 30 лет спустя (Limits to growth. The 30-year update)

вышла на английском в 2004-м году и на русском в начале 2008-го. Как

ясно из названия, эта монография — прямое развитие знаменитого «Доклада

римскому клубу» 1972-го года. За три десятка прошедших лет авторы

получили в своё распоряжение множество новых фактов, разработали более

сложные и продуманные математические модели, прогресс информационных

технологий предоставил им большие вычислительные мощности.

Как и

в исходной книге, основной идеей является то что для существующей

модели развития с её относительно быстрым ростом всех показателей

естественным станет ограничение возможностей биосферы и других земных

оболочек. Авторы не занимаются футуризмом и не пытаются предсказывать

будущее (и активно возражают против такого понимания их книг), но

представляют читателям набор сценариев развития (известный как модель

World3).

Первоначально предполагалось что в запасе у

человечества до момента прекращения роста есть ещё около полувека. Уже

во втором издании книги (За пределами роста, 1992) авторам пришлось

скорректировать свою точку зрения в пессимистическую сторону. По их

мнению, человечество уже к концу семидесятых или началу восьмидесятых

годов перешагнуло границы самоподдержания биосферы.

Кратко

перечислю основные тезисы авторов. По некоторым показателям пределы

роста уже достигнуты (производство с/х продукции на душу населения,

вылов рыбы), по другим будет достигнут в ближайшее время. Скорость

потери сельскохозяйственных земель возрастает, приходится включать в

оборот всё менее и менее ценные участки, при этом современные методы

сельскохозяйственного производства не способствуют сохранению почвы.

Всё хуже становится и ситуация с пресной водой. Подробно анализируются

также ситуация с невозобновимыми источниками сырья и энергии. Большое

внимание уделяется экономическим механизмам регулирования и

показывается их неспособность управлять развитием в глобальных

масштабах. Констатируется неспособность правительств на мировом уровне

организованно противостоять ухудшению ситуации и способствовать

переходу к устойчивому развитию. Даётся оценка развитию технологий и их

способности предотвратить развитие ситуации по пессимистическим

прогнозам.

The Limits to Growth first edition cover |

|

| Authors |

|

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Published | 2 March 1972; 50 years ago[1] |

| Publisher | Potomac Associates – Universe Books |

| Pages | 205 |

| ISBN | 0-87663-165-0 |

| OCLC | 307838 |

| digital: Digitized 1972 edition |

The Limits to Growth (LTG) is a 1972 report[2] that discussed the possibility of exponential economic and population growth with finite supply of resources, studied by computer simulation.[3] The study used the World3 computer model to simulate the consequence of interactions between the earth and human systems.[a][4] The model was based on the work of Jay Forrester of MIT,[2]: 21 as described in his book World Dynamics.[5]

Commissioned by the Club of Rome, the findings of the study were first presented at international gatherings in Moscow and Rio de Janeiro in the summer of 1971.[2]: 186 The report’s authors are Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III, representing a team of 17 researchers.[2]: 8

The report concludes that, without substantial changes in resource consumption, «the most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity». Although its methods and premises were heavily challenged on its publication, subsequent work to validate its forecasts continue to confirm that insufficient changes have been made since 1972 to significantly alter their nature.

Since its publication, some 30 million copies of the book in 30 languages have been purchased.[6] It continues to generate debate and has been the subject of several subsequent publications.[7]

Beyond the Limits and The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update were published in 1992 and 2004 respectively,[8][9] in 2012, a 40-year forecast from Jørgen Randers, one of the book’s original authors, was published as 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years,[10] and in 2022 two of the original Limits to Growth authors, Dennis Meadows and Jorgen Randers, joined 19 other contributors to produce Limits and Beyond.[11]

World3 Model Standard Run as shown in The Limits to Growth

Purpose[edit]

In commissioning the MIT team to undertake the project that resulted in LTG, the Club of Rome had three objectives:[2]: 185

- Gain insights into the limits of our world system and the constraints it puts on human numbers and activity.

- Identify and study the dominant elements, and their interactions, that influence the long-term behavior of world systems.

- To warn of the likely outcome of contemporary economic and industrial policies, with a view to influencing changes to a sustainable lifestyle.

Methodology[edit]

The World3 model is based on five variables: «population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and consumption of nonrenewable natural resources».[2]: 25 At the time of the study, all these variables were increasing and were assumed to continue to grow exponentially, while the ability of technology to increase resources grew only linearly.[2] The authors intended to explore the possibility of a sustainable feedback pattern that would be achieved by altering growth trends among the five variables under three scenarios. They noted that their projections for the values of the variables in each scenario were predictions «only in the most limited sense of the word», and were only indications of the system’s behavioral tendencies.[12] Two of the scenarios saw «overshoot and collapse» of the global system by the mid- to latter-part of the 21st century, while a third scenario resulted in a «stabilized world».[13]: 11

Exponential reserve index[edit]

A key idea in The Limits to Growth is the notion that if the rate of resource use is increasing, the number of reserves cannot be calculated by simply taking the current known reserves and dividing them by the current yearly usage, as is typically done to obtain a static index. For example, in 1972, the amount of chromium reserves was 775 million metric tons, of which 1.85 million metric tons were mined annually. The static index is 775/1.85=418 years, but the rate of chromium consumption was growing at 2.6 percent annually, or exponentially.[2]: 54–71 If instead of assuming a constant rate of usage, the assumption of a constant rate of growth of 2.6 percent annually is made, the resource will instead last

In general, the formula for calculating the amount of time left for a resource with constant consumption growth is:[14]

where:

- y = years left;

- r = the continuous compounding growth rate;

- s = R/C or static reserve;

- R = reserve;

- C = (annual) consumption.

[edit]

The chapter contains a large table that spans five pages in total, based on actual geological reserves data for a total of 19 non-renewable resources, and analyzes their reserves at 1972 modeling time of their exhaustion under three scenarios: static (constant growth), exponential, and exponential with reserves multiplied by 5 to account for possible discoveries. A short excerpt from the table is presented below:

-

Years Resource Consumption, projected average annual growth rate Static index Exponential index 5× reserves exponential index Chromium 2.6% 420 95 154 Gold 4.1% 11 9 29 Iron 1.8% 240 93 173 Lead 2.0% 26 21 64 Petroleum 3.9% 31 20 50

The chapter also contains a detailed computer model of chromium availability with current (as of 1972) and double the known reserves as well as numerous statements on the current increasing price trends for discussed metals:

Given present resources consumption rates and the projected increase in the rates, the great majority of the currently important nonrenewable resources will be extremely costly 100 years from now. (…) The prices of those resources with the shortest static reserve indices have already begun to increase. The price of mercury, for example, has gone up 500 percent in the last 20 years; the price of lead has increased 300 percent in the last 30 years.

— Chapter 2, page 66

Due to the detailed nature and use of actual resources and their real-world price trends, the indexes have been interpreted as a prediction of the number of years until the world would «run out» of them, both by environmentalist groups calling for greater conservation and restrictions on use and by skeptics criticizing the accuracy of the predictions.[15][failed verification][16][17][18] This interpretation has been widely propagated by media and environmental organizations, and authors who, apart from a note about the possibility of the future flows being «more complicated», did not clearly constrain or deny this interpretation.[19] While environmental organizations used it to support their arguments, a number of economists used it to criticize LTG as a whole shortly after publication in the 1970s (Peter Passel, Marc Roberts, and Leonard Ross), with similar criticism reoccurring from Ronald Baily, George Goodman and others in the 1990s.[20] In 2011 Ugo Bardi in «The Limits to Growth Revisited» argued that «nowhere in the book was it stated that the numbers were supposed to be read as predictions», nonetheless as they were the only tangible numbers referring to actual resources, they were promptly picked as such by both supporters as well as opponents.[20]

While Chapter 2 serves as an introduction to the concept of exponential growth modeling, the actual World3 model uses an abstract «non-renewable resources» component based on static coefficients rather than the actual physical commodities described above.

Conclusions[edit]

After reviewing their computer simulations, the research team came to the following conclusions:[2]: 23–24

- If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years.[b] The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.

- It is possible to alter these growth trends and to establish a condition of ecological and economic stability that is sustainable far into the future. The state of global equilibrium could be designed so that the basic material needs of each person on earth are satisfied and each person has an equal opportunity to realize his individual human potential.

- If the world’s people decide to strive for this second outcome rather than the first, the sooner they begin working to attain it, the greater will be their chances of success.

— Limits to Growth, Introduction

The introduction goes on to say:

These conclusions are so far-reaching and raise so many questions for further study that we are quite frankly overwhelmed by the enormity of the job that must be done. We hope that this book will serve to interest other people, in many fields of study and in many countries of the world, to raise the space and time horizons of their concerns, and to join us in understanding and preparing for a period of great transition – the transition from growth to global equilibrium.

Criticism[edit]

LTG provoked a wide range of responses, including immediate criticisms almost as soon as it was published.[21][22]

Peter Passell and two co-authors published a 2 April 1972 article in the New York Times describing LTG as «an empty and misleading work … best summarized … as a rediscovery of the oldest maxim of computer science: Garbage In, Garbage Out». Passell found the study’s simulation to be simplistic while assigning little value to the role of technological progress in solving the problems of resource depletion, pollution, and food production. They charged that all LTG simulations ended in collapse, predicting the imminent end of irreplaceable resources. Passell also charged that the entire endeavour was motivated by a hidden agenda: to halt growth in its tracks.[23]

In 1973, a group of researchers at the Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex concluded that simulations in Limits to Growth were very sensitive to a few key assumptions and suggest that the MIT assumptions were unduly pessimistic, and the MIT methodology, data, and projections were faulty.[24] However, the LTG team, in a paper entitled «A Response to Sussex», described and analyzed five major areas of disagreement between themselves and the Sussex authors.[25] The team asserted that the Sussex critics applied «micro reasoning to macro problems», and suggested that their own arguments had been either misunderstood or wilfully misrepresented. They pointed out that the critics had failed to suggest any alternative model for the interaction of growth processes and resource availability, and «nor had they described in precise terms the sort of social change and technological advances that they believe would accommodate current growth processes.»

At the time, «the very hint of any global limitation as suggested in the report […] was met with disbelief and rejection by businesses

and most economists.»[26] Critics declared that history proved the projections to be incorrect, such as the predicted resource depletion and associated economic collapse by the end of the 20th century.[27] The methodology, the computer, the conclusions, the rhetoric and the people behind the project were criticised.[28] Yale economist Henry C. Wallich agreed that growth could not continue indefinitely, but that a natural end to growth was preferable to intervention. Wallich stated that technology could solve all the problems the report was concerned about, but only if growth continued apace. By stopping growth too soon, Wallich warned, the world would be «consigning billions to permanent poverty».[28]

Julian Simon, a professor at the Universities of Illinois and, later, Maryland, argued that the fundamental underlying concepts of the LTG scenarios were faulty because the very idea of what constitutes a «resource» varies over time. For instance, wood was the primary shipbuilding resource until the 1800s, and there were concerns about prospective wood shortages from the 1500s on. But then boats began to be made of iron, later steel, and the shortage issue disappeared. Simon argued in his book The Ultimate Resource that human ingenuity creates new resources as required from the raw materials of the universe. For instance, copper will never «run out». History demonstrates that as it becomes scarcer its price will rise and more will be found, more will be recycled, new techniques will use less of it, and at some point a better substitute will be found for it altogether.[29] His book was revised and reissued in 1996 as The Ultimate Resource 2.[30]

To the US Congress in 1973, Allen V. Kneese and Ronald Riker of Resources for the Future (RFF) testified that in their view, «The authors load their case by letting some things grow exponentially and others not. Population, capital and pollution grow exponentially in all models, but technologies for expanding resources and controlling pollution are permitted to grow, if at all, only in discrete increments.» However, their testimony also noted the possibility of «relatively firm long-term limits» associated with carbon dioxide emissions, that humanity might «loose upon itself, or the ecosystem services on which it depends, a disastrously virulent substance», and (implying that population growth in «developing countries» is problematic) that «we don’t know what to do about it».[31]

In 1997, the Italian economist Giorgio Nebbia observed that the negative reaction to the LTG study came from at least four sources: those who saw the book as a threat to their business or industry; professional economists, who saw LTG as an uncredentialed encroachment on their professional perquisites; the Catholic church, which bridled at the suggestion that overpopulation was one of mankind’s major problems; finally, the political left, which saw the LTG study as a scam by the elites designed to trick workers into believing that a proletarian paradise was a pipe dream.[32]

Positive reviews[edit]

With few exceptions, economics as a discipline has been dominated by a perception of living in an unlimited world, where resource and pollution problems in one area were solved by moving resources or people to other parts. The very hint of any global limitation as suggested in the report The Limits to Growth was met with disbelief and rejection by businesses and most economists. However, this conclusion was mostly based on false premises.

– Meyer & Nørgård (2010).

In a 2008 blog post, Ugo Bardi commented that «Although, by the 1990s LTG had become everyone’s laughing stock, among some the LTG ideas are becoming again popular».[32] Reading LTG for the first time in 2000, Matthew Simmons concluded his views on the report by saying, «In hindsight, The Club of Rome turned out to be right. We simply wasted 30 important years ignoring this work.»[33] Research from the University of Melbourne has found the book’s forecasts are accurate, 40 years on.

In 2008 Graham Turner of CSIRO found that the observed historical data from 1970 to 2000 closely match the simulated results of the «standard run» limits of growth model for almost all the outputs reported. «The comparison is well within uncertainty bounds of nearly all the data in terms of both magnitude and the trends over time.» Turner also examined a number of reports, particularly by economists, which over the years have purported to discredit the limits-to-growth model. Turner says these reports are flawed, and reflect misunderstandings about the model.[13]: 37

Turner reprised these observations in another opinion piece in The Guardian in 2014. Turner used data from the UN to claim that the graphs almost exactly matched the ‘Standard Run’ from 1972 (i.e. the worst-case scenario, assuming that a ‘business as usual’ attitude was adopted, and there were no modifications of human behaviour in response to the warnings in the report). Birth rates and death rates were both slightly lower than projected, but these two effects cancelled each other out, leaving the growth in world population almost exactly as forecast.[34]

In 2010, Nørgård, Peet and Ragnarsdóttir called the book a «pioneering report», and said that it «has withstood the test of time and, indeed, has only become more relevant.»[6]

The journalist Christian Parenti, writing in 2012, sees parallels between the reception of LTG and the contemporary global warming controversy, and went on to comment, «That said, The Limits to Growth was a scientifically rigorous and credible warning that was actively rejected by the intellectual watchdogs of powerful economic interests. A similar story is playing out now around climate science.»[35]

In 2012, John Scales Avery, a member of the Nobel Prize (1995) winning group associated with the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, supported the basic thesis of LTG by stating, «Although the specific predictions of resource availability in [The] Limits to Growth lacked accuracy, its basic thesis – that unlimited economic growth on a finite planet is impossible – was indisputably correct.»[36]

Legacy[edit]

Updates and symposia[edit]

Researchers from China and Indonesia with Dennis Meadows

The Club of Rome has persisted after The Limits of Growth and has generally provided comprehensive updates to the book every five years.

An independent retrospective on the public debate over The Limits to Growth concluded in 1978 that optimistic attitudes had won out, causing a general loss of momentum in the environmental movement. While summarizing a large number of opposing arguments, the article concluded that «scientific arguments for and against each position … have, it would seem, played only a small part in the general acceptance of alternative perspectives.»[37]

In 1989, a symposium was held in Hanover, entitled «Beyond the Limits to Growth: Global Industrial Society, Vision or Nightmare?» and in 1992, Beyond the Limits (BTL) was published as a 20-year update on the original material. It «concluded that two decades of history mainly supported the conclusions we had advanced 20 years earlier. But the 1992 book did offer one major new finding. We suggested in BTL that humanity had already overshot the limits of Earth’s support capacity.»[38]

Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update was published in 2004. The authors observed that «It is a sad fact that humanity has largely squandered the past 30 years in futile debates and well-intentioned, but halfhearted, responses to the global ecological challenge. We do not have another 30 years to dither. Much will have to change if the ongoing overshoot is not to be followed by collapse during the twenty-first century.»[38]

In 2012, the Smithsonian Institution held a symposium entitled «Perspectives on Limits to Growth«.[39] Another symposium was held in the same year by the Volkswagen Foundation, entitled «Already Beyond?»[40]

Limits to Growth did not receive an official update in 2012, but one of its coauthors, Jørgen Randers, published a book, 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years.[41][42]

Validation[edit]

In 2008, physicist Graham Turner[c] at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Australia published a paper called «A Comparison of ‘The Limits to Growth’ with Thirty Years of Reality».[13] It compared the past thirty years of data with the scenarios laid out in the 1972 book and found that changes in industrial production, food production, and pollution are all congruent with one of the book’s three scenarios—that of «business as usual». This scenario in Limits points to economic and societal collapse in the 21st century.[43] In 2010, Nørgård, Peet, and Ragnarsdóttir called the book a «pioneering report». They said that, «its approach remains useful and that its conclusions are still surprisingly valid … unfortunately the report has been largely dismissed by critics as a doomsday prophecy that has not held up to scrutiny.»[6]

Also in 2008, researcher Peter A. Victor wrote that even though the Limits team probably underestimated price mechanism’s role in adjusting outcomes, their critics have overestimated it. He states that Limits to Growth has had a significant impact on the conception of environmental issues and notes that (in his view) the models in the book were meant to be taken as predictions «only in the most limited sense of the word».[12]

In a 2009 article published in American Scientist entitled Revisiting the Limits to Growth After Peak Oil, Hall and Day noted that «the values predicted by the limits-to-growth model and actual data for 2008 are very close.»[44] These findings are consistent with the 2008 CSIRO study which concluded: «The analysis shows that 30 years of historical data compares favorably with key features … [of the Limits to Growth] «standard run» scenario, which results in collapse of the global system midway through the 21st Century.»[13]

In 2011, Ugo Bardi published a book-length academic study of The Limits to Growth, its methods, and historical reception and concluded that «The warnings that we received in 1972 … are becoming increasingly more worrisome as reality seems to be following closely the curves that the … scenario had generated.»[45]: 3 A popular analysis of the accuracy of the report by science writer Richard Heinberg was also published.[46]

In 2012, writing in American Scientist, Brian Hayes stated that the model is «more a polemical tool than a scientific instrument». He went on to say that the graphs generated by the computer program should not, as the authors note, be used as predictions.[47]

In 2014, Turner concluded that «preparing for a collapsing global system could be even more important than trying to avoid collapse.»[48]

In 2015, a calibration of the updated World3-03 model using historical data from 1995 to 2012 to better understand the dynamics of today’s economic and resource system was undertaken. The results showed that human society has invested more to abate persistent pollution, increase food productivity and have a more productive service sector however the broad trends within Limits to Growth still held true.[49]

In 2016, a report published by the UK Parliament’s ‘All-Party Parliamentary Group on Limits to Growth’ concluded that «there is unsettling evidence that society is still following the ‘standard run’ of the original study – in which overshoot leads to an eventual collapse of production and living standards».[50] The report also points out that some issues not fully addressed in the original 1972 report, such as climate change, present additional challenges for human development.

In 2020, an analysis by Gaya Herrington, then Director of Sustainability Services of KPMG US,[51] was published in Yale University’s Journal of Industrial Ecology.[52] The study assessed whether, given key data known in 2020 about factors important for the «Limits to Growth» report, the original report’s conclusions are supported. In particular, the 2020 study examined updated quantitative information about ten factors, namely population, fertility rates, mortality rates, industrial output, food production, services, non-renewable resources, persistent pollution, human welfare, and ecological footprint, and concluded that the «Limits to Growth» prediction is essentially correct in that continued economic growth is unsustainable under a «business as usual» model.[52] The study found that current empirical data is broadly consistent with the 1972 projections and that if major changes to the consumption of resources are not undertaken, economic growth will peak and then rapidly decline by around 2040.[53][54]

[edit]

Books about humanity’s uncertain future have appeared regularly over the years. A few of them, including the books mentioned above for reference, include:[55]

- An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Malthus (1798);

- Road to Survival by William Vogt (1948);

- The Challenge of Man’s Future by Harrison Brown (1956);

- Mirage of Health by Rene Dubos (1959);

- The Hungry Planet by Georg Bostrom (1965);

- The Population Bomb by Paul R. Ehrlich (1968);

- The Limits to Growth (1972);

- Overshoot by William R. Catton (1980);

- State of the World reports issued by the Worldwatch Institute (produced annually since 1984);

- Our Common Future, published by the UN’s World Commission on Environment and Development (1987);

- Earth in the Balance, written by then-US senator Al Gore (1992);

- Earth Odyssey by journalist Mark Hertsgaard (1999);[55]

- The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update (2004);

- The Long Emergency by James Howard Kunstler (2005);

- Storms of My Grandchildren by James Hansen, ISBN 9781608192007 (2009);

- The Limits to Growth Revisited by Ugo Bardi, Springer Briefs in Energy, ISBN 9781441994158 (2011);

- 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years by Jørgen Randers (2012);

- 10 Billion by Stephen Emmott (2013);

- The Bet by Paul Sabin, Yale University Press (2014);

- The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert (2014);

- The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells (2017);

- Limits and Beyond edited by Ugo Bardi and Carlos Alvarez Pereira, Exapt Press, ISBN 9781914549038 (2022).

- Earth for All – A Survival Guide for Humanity (2022).[56][57][58]

Editions[edit]

- ISBN 0-87663-165-0, 1972 first edition (digital version)

- ISBN 0-87663-222-3, 1974 second edition (cloth)

- ISBN 0-87663-918-X, 1974 second edition (paperback)

- Meadows, Donella; Meadows, Dennis; Randers, Jorgen (1992). Beyond the Limits (Hardcover ed.). Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 0-930031-55-5.

- Meadows, Donella; Randers, Jorgen; Meadows, Dennis (June 2004). Limits To Growth: The 30-Year Update (Paperback ed.). Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 193149858X.

- Meadows, Donella; Randers, Jorgen; Meadows, Dennis (March 2005). Limits To Growth: The 30-Year Update (Hardcover ed.). Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 1931498512.

See also[edit]

- Attractiveness principle – Systems dynamics archetype

- Albert Allen Bartlett – American physicist (1923–2013), author of Arithmetic, Population, and Energy

- Collapsology – Study of the risks of collapse of industrial civilization

- Cornucopianism – Ideological position in futurism

- Twelve leverage points (to intervene in a system if it is to be managed) – model proposed by Donella Meadows,

- DYNAMO (programming language) – Simulation language & graphical notation

- Degrowth – Political, economic and social movement

- Ecological economics – Interdependence of human economies and natural ecosystems

- Ecological overshoot – Demands on ecosystem exceeding regeneration

- Economic growth – Measure of increase in market value of goods

- Energy crisis – Low availability of energy resources

- Energy development – Diverse methods of energy production

- The Global 2000 Report to the President – Report commissioned by President Jimmy Carter

- Global catastrophic risk – Potentially harmful worldwide events

- Hubbert peak theory – One of the primary theories on peak oil

- Jevons paradox – Efficiency leads to increased demand

- Carlos Mallmann – Argentine physicist (1928–2020), proponent of the Latin American World Model

- Malthusian catastrophe – Idea about population growth and food supply

- Overconsumption

- Overpopulation – Proposed condition wherein human numbers exceed the carrying capacity of the environment

- Peak oil – Hypothetical point in time when the maximum rate of petroleum extraction is reached

- Planetary boundaries – Limits not to be exceeded if humanity wants to survive in a safe ecosystem

- Population bottleneck – Effects of a sharp reduction in numbers on the diversity and robustness of a population

- Post-growth – Beyond optimum economic growth

- Productivism – Primacy of productivity and growth

- Richard Rainwater – American businessman and philanthropist

- Societal collapse – Fall of a complex human society

- Steady-state economy – Constant capital and population size

- System dynamics – Study of non-linear complex systems

—

- The Population Bomb – 1968 book predicting worldwide famine

- The Revenge of Gaia – 2006 book by James Lovelock

Notes[edit]

- ^ The models were run on DYNAMO, a simulation programming language.

- ^ from 1972, so 2072

- ^ Dr Turner is an Honorary Senior Fellow with the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute at the University of Melbourne.

References[edit]

- ^ «The Limits to Growth+50». Club of Rome. 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Meadows, Donella H; Meadows, Dennis L; Randers, Jørgen; Behrens III, William W (1972). The Limits to Growth; A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books. ISBN 0876631650. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ MacKenzie, Debora (4 January 2012). «Boom and doom: Revisiting prophecies of collapse». New Scientist. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Edwards, Paul N. (2010). A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming. MIT Press. pp. 366–371. ISBN 9780262290715.

- ^ Forrester, Jay Wright (1971). World Dynamics. Wright-Allen Press. ISBN 0262560186.

- ^ a b c Nørgård, Jørgen Stig; Peet, John; Ragnarsdóttir, Kristín Vala (March 2010). «The History of The Limits to Growth». The Solutions Journal. 1 (2): 59–63. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ Farley, Joshua C. «The Limits to growth debate». The University of Vermont. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ Meadows, Donella H.; Randers, Jorgen; Meadows, Dennis L. (1992). Beyond the Limits. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 0-930031-62-8.

- ^ Meadows, Donella H.; Randers, Jorgen; Meadows, Dennis L. (2004). The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. White River Junction VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co. ISBN 1931498512. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Randers, Jørgen (2012). 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years. White River Junction VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-60358-467-8. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Bardi, Ugo; Alvarez Pereira, Carlos (2022). Limits and Beyond. Exapt Press. ISBN 978-1-914549-03-8.

- ^ a b Victor, Peter A. (2008). Managing without growth : slower by design, not disaster. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. ISBN 978-1-84844-299-3. OCLC 247022295.

- ^ a b c d Turner, Graham (2008). «A Comparison of ‘The Limits to Growth’ with Thirty Years of Reality». Socio-Economics and the Environment in Discussion (SEED). CSIRO Working Paper Series. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). 2008–09: 52. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.05.001. ISSN 1834-5638. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Limits To Growth, pg 60, Derivation:

reverts to

- ^ The Skeptical Environmentalist, p. 121

- ^ «Chapter 17: Growth and Productivity-The Long-Run Possibilities». Archived from the original on 18 December 2010.

- ^ «Treading lightly». The Economist. 19 September 2002. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019.

- ^ Bailey, Ronald (4 February 2004). «Science and Public Policy». Reason. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Limits to Growth. 1972. p. 63.

Of course, the actual nonrenewable resource availability in the next few decades will be determined by factors much more complicated that can be expressed by either the simple static reserve index or the exponential reserve index. We have studied this problem with a detailed model that takes into account the many interrelationships among such factors as varying grades of ores, production costs, new mining technology, the elasticity of consumer demand, and substitution with other resources

- ^ a b Bardi, Ugo (2011). The Limits to Growth Revisited. ISBN 9781441994158.

- ^ Kaysen, Carl (1972). «The Computer That Printed out W*O*L*F*». Foreign Affairs. 50 (4): 660–668. doi:10.2307/20037939. JSTOR 20037939.

- ^ Solow, Robert M. (1973). «Is the End of the World at Hand?». Challenge. 16 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1080/05775132.1973.11469961. JSTOR 40719094.

- ^ Passell, Peter; Roberts, Marc; Ross, Leonard (2 April 1972). «The Limits to Growth». The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Cole, H. S. D.; Freeman, Christopher; Jahoda, Marie; Pavitt, K. L. R., eds. (1973). Models of doom : a critique of The limits to growth (1st, hardcover ed.). New York: Universe Publishing. ISBN 0-87663-184-7. OCLC 674851.

- ^ Meadows, Donella H; Meadows, Dennis L; Randers, Jørgen; Behrens III, William W (February 1973). «A response to Sussex». Futures. 5 (1): 135–152. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(73)90062-1.

- ^ Meyer, N. I.; Nørgård, J.S. (2010). Policy Means for Sustainable Energy Scenarios (abstract) (PDF). Denmark: International Conference on Energy, Environment and Health – Optimisation of Future Energy Systems. pp. 133–137. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ van Vuuren, D. P.; Faber, A (2009). Growing within Limits – A Report to the Global Assembly 2009 of the Club of Rome (PDF). Bilthoven: Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. p. 23. ISBN 9789069602349. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b Alan Atkisson (2010). Believing Cassandra: How to be an Optimist in a Pessimist’s World, Earthscan, p. 13.

- ^ Simon, Julian (August 1981). The Ultimate Resource (Hardcover ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069109389X.