| Goodfellas | |

|---|---|

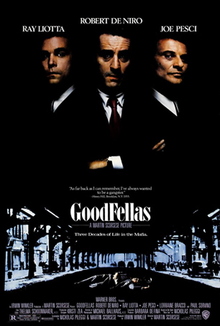

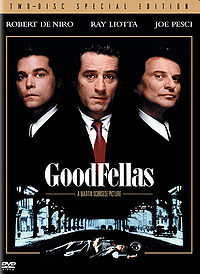

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi |

| Produced by | Irwin Winkler |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

146 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[2] |

| Box office | $47.1 million[3] |

Goodfellas (stylized GoodFellas) is a 1990 American biographical crime film directed by Martin Scorsese, written by Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese, and produced by Irwin Winkler. It is a film adaptation of the 1985 nonfiction book Wiseguy by Pileggi. Starring Robert De Niro, Ray Liotta, Joe Pesci, Lorraine Bracco and Paul Sorvino, the film narrates the rise and fall of mob associate Henry Hill and his friends and family from 1955 to 1980.

Scorsese initially titled the film Wise Guy and postponed making it; he and Pileggi later changed the title to Goodfellas. To prepare for their roles in the film, De Niro, Pesci and Liotta often spoke with Pileggi, who shared research material left over from writing the book. According to Pesci, improvisation and ad-libbing came out of rehearsals wherein Scorsese gave the actors freedom to do whatever they wanted. The director made transcripts of these sessions, took the lines he liked most and put them into a revised script, which the cast worked from during principal photography.

Goodfellas premiered at the 47th Venice International Film Festival on September 9, 1990, where Scorsese was awarded with Silver Lion for Best Director, and was released in the United States on September 19, 1990, by Warner Bros. The film was made on a budget of $25 million and grossed $47 million. Goodfellas received widespread critical acclaim upon release: the critical consensus on Rotten Tomatoes calls it «arguably the high point of Martin Scorsese’s career». The film was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, with Pesci winning for Best Supporting Actor. The film won five awards from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, including Best Film and Best Director. Additionally, Goodfellas was named the year’s best film by various critics’ groups.

Goodfellas is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, particularly in the gangster genre. In 2000, it was deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant» and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the United States Library of Congress.[4][5] Its content and style have been emulated in numerous other films and television series.[6]

Plot[edit]

In 1955, youngster Henry Hill becomes enamored by the criminal life and Mafia presence in his working class Italian-American neighborhood in Brooklyn. He begins working for local caporegime Paulie Cicero and his associates: Jimmy «the Gent» Conway, an Irish-American truck hijacker and gangster, and Tommy DeVito, a fellow juvenile delinquent. Henry begins as a fence for Jimmy, gradually working his way up to more serious crimes. The three associates spend most of their nights in the 1960s at the Copacabana nightclub carousing with women. Henry starts dating Karen Friedman, a Jewish woman who is initially troubled by Henry’s criminal activities. Seduced by Henry’s glamorous lifestyle, she marries him despite her parents’ disapproval.

In 1970, Billy Batts, a made man in the Gambino crime family recently released from prison, patronizes Tommy at a nightclub owned by Henry; Tommy and Jimmy beat, stab and fatally shoot Billy. The unsanctioned murder of a made man invites retribution; realizing this, Jimmy, Henry, and Tommy bury the body in upstate New York. Six months later, however, Jimmy learns that the burial site is slated for development, prompting them to exhume and relocate the decomposing corpse.

In 1974, Henry witnesses Tommy murder Spider, an errand boy, after exchanging insults with him during a card game. Karen discovers Henry has a mistress and threatens him at gunpoint. Henry moves in with his mistress, but Paulie insists that he should return to Karen after collecting a debt from a gambler in Tampa with Jimmy. Upon returning, Jimmy and Henry are arrested after being turned in by the gambler’s sister, an FBI typist, and they receive ten-year prison sentences. To support his family on the outside, Henry has Karen smuggle in drugs and sells them to a fellow inmate from Pittsburgh.

In 1978, Henry is paroled and expands his cocaine business with Jimmy and Tommy against Paulie’s orders. Jimmy organizes a crew to raid the Lufthansa vault at John F. Kennedy International Airport, stealing six million dollars in cash and jewelry. After some members purchase expensive items against Jimmy’s orders and the getaway truck is found by police, he has most of the crew (except Tommy and Henry) murdered. In 1979, Tommy is deceived into believing he is to become a made man and is murdered after walking into the room of the ceremony—partly as retribution for murdering Batts.

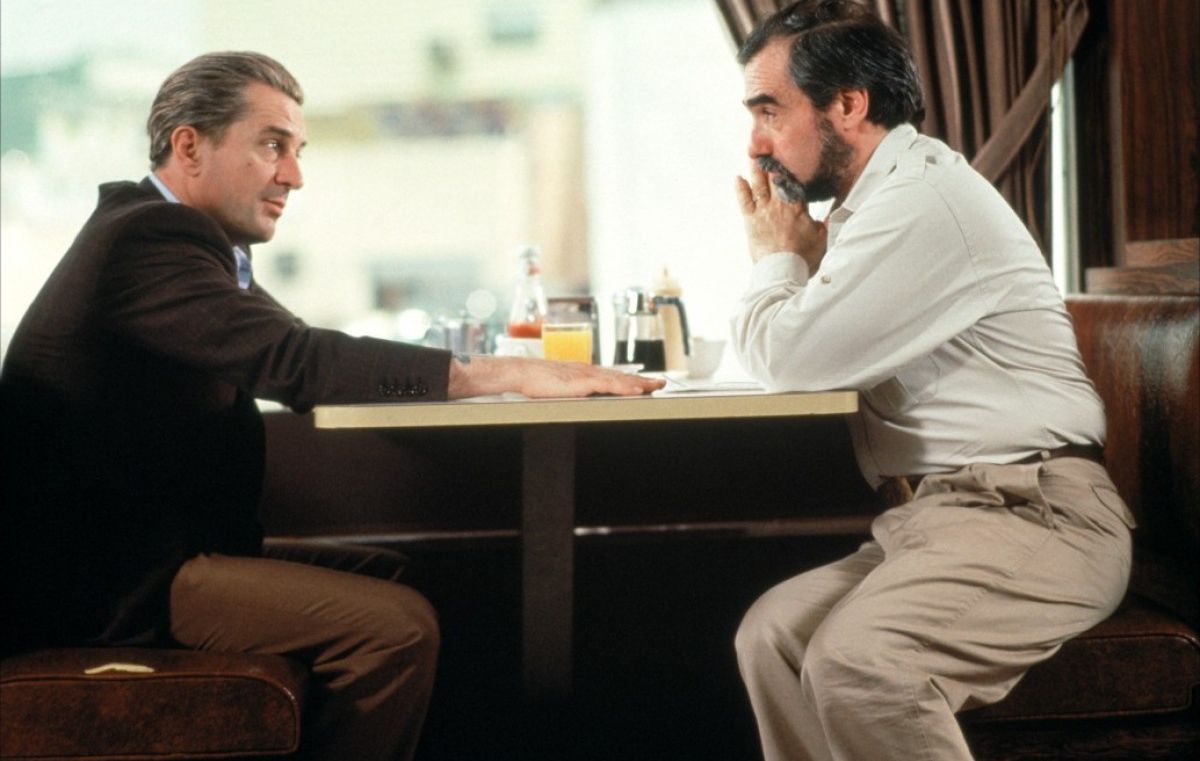

By 1980, Henry develops a drug habit and becomes a paranoid wreck. He sets up another drug deal with his Pittsburgh associates, but he is arrested by narcotics agents and incarcerated. After bailing him out, Karen reveals that she flushed $60,000 worth of cocaine down the toilet to prevent FBI agents from finding it during their raid, leaving them penniless. Feeling betrayed by Henry’s drug dealing, Paulie gives him $3,200 and ends their association. Karen goes to Jimmy for help, but eventually flees upon suspecting a trap to murder her. Henry later meets Jimmy at a diner and is asked to travel on a hit assignment, but the novelty of such a request makes Henry suspicious. Realizing that Jimmy also plans to have him killed, Henry finally decides to become an informant and enroll, with his family, into the witness protection program. Henry gives sufficient testimony and evidence in court to have Paulie and Jimmy convicted, and moves to a nondescript neighborhood, unhappy to leave his exciting gangster life to live as a boring, average «schnook».

The end title cards state that (as of 1990, when the film was released) Henry is still a protected witness but that he was arrested in 1987 in Seattle for narcotics conspiracy. Henry received five years of probation but has since been clean. He and Karen separated in 1989, and Paulie died the previous year in Fort Worth Federal Prison from respiratory illness. Jimmy is serving a 20 years-to-life sentence in a New York prison for murder and would be eligible for parole in 2004.

Cast[edit]

- Robert De Niro as James Conway[7]

- Ray Liotta as Henry Hill

- Joe Pesci as Tommy DeVito

- Lorraine Bracco as Karen Hill

- Paul Sorvino as Paul Cicero[7]

- Frank Sivero as Frankie Carbone

- Tony Darrow as Sonny Bunz

- Mike Starr as Frenchy

- Frank Vincent as Billy Batts

- Chuck Low as Morris Kessler

- Frank DiLeo as Tuddy Cicero

- Henny Youngman as Himself

- Gina Mastrogiacomo as Janice Rossi

- Catherine Scorsese as Tommy’s mother

- Charles Scorsese as Vinnie

- Suzanne Shepard as Karen’s mother

- Debi Mazar as Sandy

- Margo Winkler as Belle Kessler

- Welker White as Lois Byrd

- Jerry Vale as Himself

- Julie Garfield as Mickey Conway

- Christopher Serrone as Young Henry

- Elaine Kagan as Henry’s mother

- Beau Starr as Henry’s father

- Kevin Corrigan as Michael Hill

- Michael Imperioli as Spider

- Robbie Vinton as Bobby Vinton

- John Williams as Johnny Roastbeef

- Illeana Douglas as Rosie

- Frank Pellegrino as Johnny Dio

- Tony Sirico as Tony Stacks

- Samuel L. Jackson as Stacks Edwards

- Paul Herman as Dealer

- Edward McDonald as Himself

- Louis Eppolito as Fat Andy

- Tony Lip as Frankie the Wop

- Anthony Powers as Jimmy Two Times

- Vinny Pastore as Man w/Coatrack

- Tobin Bell as Parole Officer

- Isiah Whitlock Jr. as Doctor

- Richard «Bo» Dietl as Arresting Narc

- Ed Deacy as Detective Deacy

- Victor Colicchio as Henry’s 60’s crew

- Vincent Gallo as Henry’s 70’s crew

- Joseph Bono as Mikey Franzese

- Katherine Wallach as Diane

- Bob Golub as Truck Driver at Diner

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Martin Scorsese, the director of the film, in 2006

Goodfellas is based on New York crime reporter Nicholas Pileggi’s book Wiseguy.[8] Martin Scorsese did not intend to make another mob film, but he saw a review of Pileggi’s book, which he then read while working on the set of The Color of Money in 1986.[9][10] He had always been fascinated by the mob lifestyle and was drawn to Pileggi’s book because he thought it was the most honest portrayal of gangsters he had ever read.[11] After reading the book, Scorsese knew what approach he wanted to take, «To begin Goodfellas like a gunshot and have it get faster from there, almost like a two-and-a-half-hour trailer. I think it’s the only way you can really sense the exhilaration of the lifestyle, and to get a sense of why a lot of people are attracted to it.»[12] According to Pileggi, Scorsese cold-called the writer and told him, «I’ve been waiting for this book my entire life,» to which Pileggi replied, «I’ve been waiting for this phone call my entire life.»[13][14]

Scorsese decided to postpone making the film when funds materialized in 1988 to make The Last Temptation of Christ. He was drawn to the documentary aspects of Pileggi’s book. «The book [Wiseguy] gives you a sense of the day-to-day life, the tedium, how they work, how they take over certain nightclubs, and for what reasons. It shows how it’s done.»[13] He saw Goodfellas as the third film in an unplanned trilogy of films that examined the lives of Italian Americans «from slightly different angles.»[15] He has often described the film as «a mob home movie» that is about money, because «that’s what they’re really in business for.»[11] Two weeks in advance of the filming, the real Henry Hill was paid $480,000.[16]

Screenplay[edit]

Scorsese and Pileggi collaborated on the screenplay, and over the course of the 12 drafts it took to reach the ideal script, the reporter realized «the visual styling had to be completely redone… So we decided to share credit.»[13][16] They chose the sections of the book they liked and put them together like building blocks.[2] Scorsese persuaded Pileggi that they did not need to follow a traditional narrative structure. The director wanted to take the gangster film and deal with it episode by episode, but start in the middle and move backwards and forwards. Scorsese compacted scenes, realizing that, if they were kept short, «the impact after about an hour and a half would be terrific.»[2] He wanted to do the voiceover like the opening of Jules and Jim (1962) and use «all the basic tricks of the New Wave from around 1961.»[2] The names of several real-life gangsters were altered for the film: Tommy «Two Gun» DeSimone became the character Tommy DeVito; Paul Vario became Paulie Cicero, and Jimmy «The Gent» Burke was portrayed as Jimmy Conway.[16] Scorsese initially titled the film Wise Guy, but later, he and Pileggi decided to change the title of their film to Goodfellas because two contemporary projects, the 1986 Brian De Palma film Wise Guys and the 1987–1990 TV series Wiseguy, had used similar titles.[2]

Casting[edit]

Once Robert De Niro agreed to play Jimmy Conway, Scorsese was able to secure the money needed to make the film.[10] Ray Liotta, who played Henry Hill, had read Pileggi’s book when it came out and was fascinated by it. A couple of years afterward, his agent told him Scorsese was going to direct a film adaptation. In 1988, Liotta met Scorsese over a period of a couple of months and auditioned for the film.[11] He campaigned aggressively for a role, though the studio wanted a well-known actor; he later said, «I think they would’ve rather had Eddie Murphy than me.»[17] The director cast Liotta after De Niro saw him in Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild (1986); Scorsese was surprised by «his explosive energy» in that film.[15] Al Pacino[18] and John Malkovich were considered for the role of Conway, and Sean Penn, Alec Baldwin, Val Kilmer, and Tom Cruise were considered for the role of Hill.[19][20][21]

To prepare for the role, De Niro consulted with Pileggi, who had research material that had been discarded while writing the book.[22] De Niro often called Hill several times a day to ask how Burke walked, held his cigarette, and so on.[23][24] Driving to and from the set, Liotta listened to FBI audio cassette tapes of Hill, so he could practice speaking like his real-life counterpart.[24] Madonna was considered for the role of Karen Hill.[19] To research her role, Lorraine Bracco tried to get close to a mob wife but was unable to, because they exist in a very tight-knit community. She decided not to meet the real Karen, saying she «thought it would be better if the creation came from me. I used her life with her parents as an emotional guideline for the role.»[25] Paul Sorvino had no problem finding the voice and walk of his character, but found it challenging finding what he called «that kernel of coldness and absolute hardness that is antithetical to my nature except when my family is threatened.»[26]

Former EDNY prosecutor Edward A. McDonald appeared in the film as himself, re-creating the conversation he had with Henry and Karen Hill about joining the Witness Protection Program. McDonald, who was friends with Pileggi, was cast on a whim; while a location scout was taking pictures of his office, McDonald casually remarked that he would be happy to play himself if needed. Pileggi called him an hour later asking if he was serious, and he was cast. The scene was unscripted, with McDonald improvising the line referring to Karen as a «babe-in-the-woods.»[27]

Photography[edit]

The film was shot on location in Queens, New York state, New Jersey, and parts of Long Island during the spring and summer of 1989, with a budget of $25 million.[16] Scorsese broke the film down into sequences and storyboarded everything because of the complicated style throughout. The filmmaker stated, «[I] wanted lots of movement and I wanted it to be throughout the whole picture, and I wanted the style to kind of break down by the end, so that by [Henry’s] last day as a wise guy, it’s as if the whole picture would be out of control, give the impression he’s just going to spin off the edge and fly out.»[9] He added that the film’s style comes from the first two or three minutes of Jules and Jim (1962): extensive narration, quick edits, freeze frames, and multiple locale switches.[12] It was this reckless attitude towards convention that mirrored the attitude of many of the gangsters in the film. Scorsese remarked, «So if you do the movie, you say, ‘I don’t care if there’s too much narration. Too many quick cuts?—That’s too bad.’ It’s that kind of really punk attitude we’re trying to show.»[12] He adopted a frenetic style to almost overwhelm the audience with images and information.[2] He also put plenty of detail in every frame because he believed the gangster life is so rich. Freeze-frames were used because Scorsese wanted images that stopped «because a point was being reached» in Henry’s life.[2]

Joe Pesci did not judge his character but found the scene where he kills Spider for talking back to his character hard to do, because he had trouble justifying the action until he forced himself to feel the way Tommy did.[11] Bracco found the shoot to be an emotionally difficult one because it was such a male-dominated cast, and she realized if she did not make her «work important, it would probably end up on the cutting room floor.»[11] When it came to the relationship between Henry and Karen, Bracco saw no difference between an abused wife and her character.[11]

According to Pesci, improvisation and ad-libbing came out of rehearsals wherein Scorsese let the actors do whatever they wanted. He made transcripts of these sessions, took the lines the actors came up with that he liked best, and put them into a revised script that the cast worked from during principal photography.[22] For example, the scene where Tommy tells a story and Henry is responding to him—the «Funny how? Do I amuse you?» scene—is based on an actual event that Pesci experienced. Pesci was working as a waiter when he thought he was making a compliment to a mobster by saying he was «funny»; however, the comment was not taken well.[28][29] It was worked on in rehearsals where he and Liotta improvised, and Scorsese recorded four to five takes, rewrote their dialogue, and inserted it into the script.[30] The dinner scene with Tommy’s mother was largely improvised. Her painting of the bearded man with the dogs was based on a photograph from National Geographic magazine.[31] The cast did not meet Henry Hill until a few weeks before the film’s premiere. Liotta met him in an undisclosed city; Hill had seen the film and told the actor that he loved it.[11]

The long tracking shot through the Copacabana nightclub came about because of a practical problem: the filmmakers could not get permission to go in the short way, and this forced them to go round the back.[2] Scorsese decided to film the sequence in one unbroken shot in order to symbolize that Henry’s entire life was ahead of him, commenting, «It’s his seduction of her [Karen] and it’s also the lifestyle seducing him.»[2] This sequence was shot eight times.[30]

Henry’s last day as a wise guy was the hardest part of the film for Scorsese to shoot because he wanted to properly show Henry’s state of anxiety, paranoia, and racing thoughts caused by cocaine and amphetamines intoxication.[2] In an interview with movie critic Mark Cousins, Scorsese explained the reason for Pesci shooting at the camera at the end of the film, «well that’s a reference right to the end of The Great Train Robbery, that’s the way that ends, that film, and basically the plot of this picture is very similar to The Great Train Robbery. It hasn’t changed, 90 years later, it’s the same story, the gun shots will always be there, he’s always going to look behind his back, he’s gotta have eyes behind his back, because they’re gonna get him someday.» The director ended the film with Henry regretting that he is no longer a wise guy, about which Scorsese said, «I think the audience should get angry at him and I would hope they do—and maybe with the system which allows this.»[2]

Post-production[edit]

Scorsese wanted to depict the film’s violence realistically, «cold, unfeeling and horrible. Almost incidental.»[10] However, he had to remove 10 frames of blood to ensure an R rating from the MPAA.[15] With a budget of $25 million, Goodfellas was Scorsese’s most expensive film to that point but still only a medium-sized budget by Hollywood standards. It was also the first time he was obliged by Warner Bros. to preview the film. It was shown twice in California, and a lot of audiences were «agitated» by Henry’s last day as a wise guy sequence. Scorsese argued that that was the point of the scene.[2] Scorsese and the film’s editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, made this sequence faster with more jump cuts to convey Henry’s drug-addled point of view. In the first test screening there were 40 walkouts in the first ten minutes.[30] One of the favorite scenes for test audiences was the «Do I amuse you?» scene.[2]

Soundtrack[edit]

While there is no incidental score as such in the film, Scorsese chose songs for the soundtrack that he felt obliquely commented on the scene or the characters.[15] In a given scene, he used only music contemporary to or older than the scene’s setting. According to Scorsese, a lot of non-dialogue scenes were shot to playback. For example, he had «Layla» by Derek and the Dominos playing on the set while shooting the scene where the dead bodies are discovered in the car, dumpster, and meat truck. Sometimes, the lyrics of songs were put between lines of dialogue to comment on the action.[2] Some of the music Scorsese had written into the script, while other songs he discovered during the editing phase.[30]

Release[edit]

Theatrical[edit]

Goodfellas premiered at the 47th Venice International Film Festival, where Scorsese received the Silver Lion award for best director.[32] It was given a wide release in North America on September 21, 1990.

Home media[edit]

Goodfellas was released on DVD in March 1997, in a single-disc, double-sided, single-layer format that requires the disc to be flipped during viewing; in 2004, Warner Home Video released a two-disc, dual-layer version, with remastered picture and sound, and bonus materials such as commentary tracks.[33] In early 2007, the film became available on single Blu-ray with all the features from the 2004 release; an expanded Blu-ray version was released on February 16, 2010, for its 20th anniversary,[34] bundled with a disc with features that include the 2008 documentary Public Enemies: The Golden Age of the Gangster Film.[33] On May 5, 2015, a 25th anniversary edition was released.[35] The film was released on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray on December 6, 2016.[36]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Goodfellas grossed $6.3 million from 1,070 theaters in opening weekend, topping the box office.[37] In its second weekend the film made $5.9 million from 1,291 theaters, falling just 8% and finishing second behind newcomer Pacific Heights.[38] It went on to make $46.8 million domestically.[39][3]

Critical response[edit]

According to review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, 96% of 107 critics have given the film a positive review, with an average rating of 9.00/10. The website’s critics consensus reads, «Hard-hitting and stylish, GoodFellas is a gangster classic—and arguably the high point of Martin Scorsese’s career.»[40] Metacritic has assigned the film a weighted average score of 90 out of 100 based on reviews from 21 critics, indicating «universal acclaim».[41] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of «A−» on an A+ to F scale.[42]

In his review for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert gave the film a full four stars and wrote, «No finer film has ever been made about organized crime – not even The Godfather.»[43] In his review for the Chicago Tribune, Gene Siskel wrote, «All of the performances are first-rate; Pesci stands out, though, with his seemingly unscripted manner. GoodFellas is easily one of the year’s best films.»[44] Both named it as the best film of 1990. In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote, «More than any earlier Scorsese film, Goodfellas is memorable for the ensemble nature of the performances… The movie has been beautifully cast from the leading roles to the bits. There is flash also in some of Mr. Scorsese’s directorial choices, including freeze frames, fast cutting and the occasional long tracking shot. None of it is superfluous.»[45] USA Today gave the film four out of four stars and called it, «great cinema—and also a whopping good time.»[12] David Ansen, in his review for Newsweek magazine, wrote «Every crisp minute of this long, teeming movie vibrates with outlaw energy.»[46] Rex Reed said, «Big, rich, powerful and explosive. One of Scorsese’s best films! Goodfellas is great entertainment.»[47] In his review for Time, Richard Corliss wrote, «So it is Scorsese’s triumph that GoodFellas offers the fastest, sharpest 2½-hr. ride in recent film history.»[48]

Lists[edit]

The film was ranked the best of 1990 by Roger Ebert,[49] Gene Siskel,[49] and Peter Travers.[50] In a poll of 80 film critics, «Goodfellas» was named the best film of the year by 34 critics. Director Martin Scorsese was chosen as the year’s best director in 45 of the 80 ballots.[51]

Goodfellas is ranked No. 92 on the AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) list, published in 2007. In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed Goodfellas as the fifteenth best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its membership.[52] In the 2012 Sight & Sound polls, it was ranked the 48th-greatest film ever made in the directors’ poll.[53] Goodfellas is 39th on James Berardinelli’s 2014-made list of the top 100 films of all time.[54] In 2015, Goodfellas ranked 20th on BBC’s «100 Greatest American Films» list, voted on by film critics from around the world.[55]

Accolades[edit]

It became one of the seven films to win Best Picture from three out of four major U.S. film critics’ groups (LA, NBR, NY, NSFC) along with Nashville, All the President’s Men, Terms of Endearment, Pulp Fiction, The Hurt Locker, and Drive My Car.

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Award | Best Picture[56] | Irwin Winkler | Nominated |

| Best Director[56] | Martin Scorsese | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor[56] | Joe Pesci | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress[56] | Lorraine Bracco | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay[56] | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing[56] | Thelma Schoonmaker | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Award | Best Motion Picture – Drama[57] | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Nominated |

| Best Director[57] | Martin Scorsese | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor[57] | Joe Pesci | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress[57] | Lorraine Bracco | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay[57] | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Won | |

| Best Actor | Robert De Niro | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Thelma Schoonmaker | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Richard Bruno | Won | |

| Directors Guild of America Award | Outstanding Directing – Feature | Martin Scorsese | Nominated |

| Writers Guild of America Award | Best Adapted Screenplay | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Nominated |

| César Award | Best Non-French Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Nominated |

| Venice Film Festival | Silver Lion for Best Director[58] | Martin Scorsese | Won |

| Audience Award | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Filmcritica «Bastone Bianco» Award | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Actor | Robert De Niro | Won | |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Joe Pesci | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Lorraine Bracco | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus | Won | |

| National Board of Review Award | Best Supporting Actor | Joe Pesci | Won |

| Boston Society of Film Critics Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Joe Pesci | Won | |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Joe Pesci | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Lorraine Bracco | Won | |

| Best Screenplay | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Won | |

| National Society of Film Critics Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Bodil Award | Best American Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

Legacy[edit]

Goodfellas is No. 94 on the American Film Institute’s «100 Years, 100 Movies» list and moved up to No. 92 on its AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) from 2007. In June 2008, the AFI put Goodfellas at No. 2 on their AFI’s 10 Top 10—the best ten films in ten «classic» American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the movie-related community.[59] Goodfellas was regarded as the second-best in the gangster film genre (after The Godfather).[60] In 2000, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film «culturally significant» and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Roger Ebert named Goodfellas the «best mob movie ever» and placed it among the ten best films of the 1990s.[61] In December 2002, a UK film critics poll in Sight & Sound ranked the film No. 4 on their list of the 10 Best Films of the Last 25 Years.[62] Time included Goodfellas in their list of Time’s All-Time 100 Movies.[63] Channel 4 placed Goodfellas at No. 10 in their 2002 poll The 100 Greatest Films, Empire listed Goodfellas at No. 6 on their «500 Greatest Movies Of All Time,»[64] and Total Film voted Goodfellas No. 1 as the greatest film of all time.[65]

Premiere listed Joe Pesci’s Tommy DeVito as No. 96 on its list of «The 100 Greatest Movie Characters of All Time,» calling him «perhaps the single most irredeemable character ever put on film.»[66] Empire ranked Tommy DeVito No. 59 in their «The 100 Greatest Movie Characters» poll.[67]

Goodfellas inspired director David Chase to make the HBO television series The Sopranos.» He told Peter Bogdanovich, «Goodfellas is a very important movie to me and Goodfellas really plowed that … I found that movie very funny and brutal and it felt very real. And yet that was the first mob movie that Scorsese ever dealt with a mob crew. … as opposed to say The Godfather … which there’s something operatic about it, classical, even the clothing and the cars. You know I mean I always think about Goodfellas when they go to their mother’s house that night when they’re eating, you know when she brings out her painting, that stuff is great. I mean The Sopranos learned a lot from that.»[68] Indeed, the film shares a total of 27 actors with The Sopranos,[69] including Bracco, Sirico, Imperioli, Pellegrino, Lip, and Vincent, who all had major roles in Chase’s HBO series.

July 24, 2010 marked the 20th anniversary of the film’s release. This milestone was celebrated with Henry Hill hosting a private screening for a select group of invitees at the Museum of the American Gangster, in New York City.[70]

In January 2012, it was announced that the AMC Network had put a television series version of the movie in development. Pileggi was on board to co-write the adaptation with television writer-producer Jorge Zamacona. The two were set to executive produce with the film’s producer Irwin Winkler and his son, David.[71]

Luc Besson’s 2013 crime comedy film The Family features a sequence where Giovanni Manzoni (Goodfellas star De Niro), a gangster who is under witness protection for testifying against a member of his family, watches Goodfellas.[72]

In 2014, the ESPN-produced 30 for 30 series debuted Playing for the Mob,[73] the story about how Hill and his Pittsburgh associates, and several Boston College basketball players, committed the point shaving scandal during the 1978–79 season, an episode briefly mentioned in the movie. The documentary, narrated by Liotta, was set up so that the viewer needed to watch the film beforehand in order to understand many of the references in the story.

In 2015, Goodfellas closed the Tribeca Film Festival with a screening of its 25th-anniversary remaster.[74]

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movies — #94

- AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) — #92

- AFI’s 10 Top 10 — #2 Gangster film

- AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Heroes and Villains — Tommy DeVito — Nominated Villain

- AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movie Quotes — «Funny how?» — Nominated Quote

References[edit]

- ^ «Goodfellas (18)». British Board of Film Classification. September 17, 1990. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Thompson, David; Christie, Ian (1996). «Scorsese on Scorsese». Faber and Faber. pp. 150–161. ISBN 9780571178278.

- ^ a b «Goodfellas (1990) — Financial Information». The Numbers. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ «Librarian of Congress Names 25 More Films to National Film Registry». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ «Complete National Film Registry Listing». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ Merrie, Stephanie (April 29, 2015). «‘Goodfellas’ is 25. Here’s an incomplete list of all the movies that have ripped it off». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ a b «Goodfellas review – a brash, menacing hightail through the death of the mob». The Guardian. January 19, 2017. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Vlastelica, Ryan (September 18, 2015). «Goodfellas turned Wiseguy’s simple prose into cinematic gold». The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Malcolm, Derek (September–October 1990). «Made Men». Film Comment.

- ^ a b c Goodwin, Richard. «The Making of Goodfellas«. Hotdog.

- ^ a b c d e f g Linfield, Susan (September 16, 1990). «Goodfellas Looks at the Banality of Mob Life». The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Mike (September 19, 1990). «GoodFellas step from his childhood». USA Today.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Mary Pat (1991). Martin Scorsese: A Journey. Thunder’s Mouth Press. ISBN 9780938410799.

- ^ «The Making of Goodfellas». Empire Magazine. November 1990. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Gilbert, Matthew (September 16, 1990). «Scorsese Tackles the Mob». Boston Globe.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, Howard (August 22, 2006). Crime Wave: The Filmgoers’ Guide to the Great Crime Movies. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-1845112196.

- ^ Portman, Jamie (October 1, 1990). «Goodfellas Star Prefers Quiet Life». Toronto Star.

- ^ «50 genius facts about GoodFellas». Shortlist. February 11, 2011.

- ^ a b «Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas: A Complete Oral History». gq.com. September 20, 2010.

- ^ «Alec Baldwin auditioned to play Henry Hill in ‘Goodfellas’«. Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Caulfield, Rachel Maresca, Philip. «‘Goodfellas’ at 25: Here are 25 things you never knew about Martin Scorsese’s mobster flick». New York Daily News.

- ^ a b Arnold, Gary (September 25, 1990). «Real Fellas Talk about Mob Film». The Washington Times.

- ^ Wolf, Buck (November 8, 2005). «Rap Star 50 Cent Joins Movie Mobsters». ABC News. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ^ a b Papamichael, Stella (October 22, 2004). «GoodFellas: Special Edition DVD (1990)». BBC. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ^ Witchel, Alex (September 27, 1990). «A Mafia Wife Makes Lorraine Bracco a Princess». The New York Times.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (October 12, 1990). «At the Movies». The New York Times.

- ^ Slater, Dan (May 21, 2008). «A Q&A With «Goodfellas» Actor (and Dechert Lawyer) Ed McDonald». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ «One of the most famous scenes in ‘Goodfellas’ is based on something that actually happened to Joe Pesci». Business Insider. May 4, 2015. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Anastasia, George; Macnow, Glen (2011). The Ultimate Book of Gangster Movies: Featuring the 100 Greatest Gangster Films of All Time. Running Press. ISBN 9780762441549. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Kaplan, Jonah; Altobellow, Stephen (Producer); Schwartz, Jeffrey (Producer) (November 19, 2004). Getting Made: The Making of Goodfellas (Documentary short). Automat Pictures.

- ^ Godfrey, Alex (November 2013). «Whaddya want from me?». mrgodfrey. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Malcolm, Derek (September 17, 1990). «The Venice Film Festival ends in uproar». The Guardian.

- ^ a b Gilchrist, Todd (February 10, 2010). «Making The (Up) Grade: Goodfellas«. Moviefone. Archived from the original on August 27, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ «GoodFellas Blu-ray 20th Anniversary Edition». Archived from the original on October 30, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ «GoodFellas Blu-ray 25th Anniversary Edition». Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ «GoodFellas 4K Blu-ray». Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Pat H. Broeske (September 24, 1990). «‘GoodFellas’ Claims No. 1 at Box Office». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Pat H. Broeske (October 1, 1990). «‘Pacific Heights’ Tops Box Office; ‘GoodFellas’ 2nd : Movies: ‘Ghost,’ third place in ticket sales, shows no signs of dying». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ «Goodfellas». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ «Goodfellas (1990)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ «Goodfellas (1990)». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ «CinemaScore». CinemaScore. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ «GoodFellas». Chicago Sun-Times. September 2, 1990. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (September 21, 1990). «Scorsese’s ‘Goodfellas’ One of the Year’s Best». Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (September 19, 1990). «A Cold-Eyed Look at the Mob’s Inner Workings». The New York Times.

- ^ Ansen, David (September 17, 1990). «A Hollywood Crime Wave». Newsweek.

- ^ Reed, Rex (September 24, 1990). «Goodfellas». New York Magazine.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (September 24, 1990). «Married to the Mob». Time. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ a b «Siskel and Ebert Top Ten Lists (1969–1998)». Innermind.com. May 3, 2012. Archived from the original on April 26, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ «Peter Travers’ Top Ten Lists 1989–2005». caltech.edu. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ McGilligan, Pat; Rowl, Mark (January 12, 1992). «AND THE WINNER IS…» The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ «The 75 Best Edited Films». Editors Guild Magazine. 1 (3). May 2012. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Christie, Ian, ed. (August 1, 2012). «The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time». Sight & Sound. British Film Institute (September 2012). Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (2014). «Berardinelli’s All Time Top 100». Reelviews.net. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ «100 Greatest American Films». BBC. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f «The 63rd Academy Awards (1991)». Oscars.org. Archived from the original on March 22, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e «HFPA – Awards Search». Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ «47th Venice Film Festival». FilmAffinity. 1990. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years Movies: Ballot» (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 14, 2018.

- ^ «AFI’s 10 Top 10». American Film Institute. June 17, 2008. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ «Best Films of the ’90s». At the Movies with Ebert & Roeper. February 27, 2000. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ «Modern Times». Sight and Sound. December 2002. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (February 12, 2005). «All-Time 100 Movies». Time. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ «The 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time». Empire. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- ^ «Goodfellas named «greatest movie»«. BBC News. October 25, 2005. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ «The 100 Greatest Movie Characters of All Time». Premiere. Archived from the original on March 17, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ «The 100 Greatest Movie Characters». Empire. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- ^ «HBO: The Sopranos: Interview with Peter Bogdanovich». HBO. 1999. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ «50 genius facts about GoodFellas». ShortList. February 11, 2011. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ «Goodfellas’ Henry Hill Back in NYC for 20th Anniversary». WPIX. July 24, 2010. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (January 10, 2012). «‘Goodfellas’ Series in the Works at AMC With Film’s Nicholas Pileggi & Irwin Winkler». Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ^ Bibbiani, William (September 11, 2013). «Exclusive Interview: Luc Besson on The Family». CraveOnline. Archived from the original on May 6, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ 30 for 30: Playing for the Mob. ESPN. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Cox, Gordon. «‘GoodFellas’ Anniversary Screening, Event to Close 2015 Tribeca Film Festival». Variety. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Kelly, Mary Pat (2003). Martin Scorsese: A Journey. Thunder’s Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-470-6.

- Pileggi, Nicholas; Scorsese, Martin (1990). Goodfellas. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-16265-9.

- Pileggi, Nicholas (1990). Wiseguy. Rei Mti. ISBN 978-0-671-72322-4.

- Thompson, David; Christie, Ian (2004). Scorsese on Scorsese. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22002-1.

External links[edit]

| Goodfellas | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi |

| Produced by | Irwin Winkler |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

146 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[2] |

| Box office | $47.1 million[3] |

Goodfellas (stylized GoodFellas) is a 1990 American biographical crime film directed by Martin Scorsese, written by Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese, and produced by Irwin Winkler. It is a film adaptation of the 1985 nonfiction book Wiseguy by Pileggi. Starring Robert De Niro, Ray Liotta, Joe Pesci, Lorraine Bracco and Paul Sorvino, the film narrates the rise and fall of mob associate Henry Hill and his friends and family from 1955 to 1980.

Scorsese initially titled the film Wise Guy and postponed making it; he and Pileggi later changed the title to Goodfellas. To prepare for their roles in the film, De Niro, Pesci and Liotta often spoke with Pileggi, who shared research material left over from writing the book. According to Pesci, improvisation and ad-libbing came out of rehearsals wherein Scorsese gave the actors freedom to do whatever they wanted. The director made transcripts of these sessions, took the lines he liked most and put them into a revised script, which the cast worked from during principal photography.

Goodfellas premiered at the 47th Venice International Film Festival on September 9, 1990, where Scorsese was awarded with Silver Lion for Best Director, and was released in the United States on September 19, 1990, by Warner Bros. The film was made on a budget of $25 million and grossed $47 million. Goodfellas received widespread critical acclaim upon release: the critical consensus on Rotten Tomatoes calls it «arguably the high point of Martin Scorsese’s career». The film was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, with Pesci winning for Best Supporting Actor. The film won five awards from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, including Best Film and Best Director. Additionally, Goodfellas was named the year’s best film by various critics’ groups.

Goodfellas is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, particularly in the gangster genre. In 2000, it was deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant» and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the United States Library of Congress.[4][5] Its content and style have been emulated in numerous other films and television series.[6]

Plot[edit]

In 1955, youngster Henry Hill becomes enamored by the criminal life and Mafia presence in his working class Italian-American neighborhood in Brooklyn. He begins working for local caporegime Paulie Cicero and his associates: Jimmy «the Gent» Conway, an Irish-American truck hijacker and gangster, and Tommy DeVito, a fellow juvenile delinquent. Henry begins as a fence for Jimmy, gradually working his way up to more serious crimes. The three associates spend most of their nights in the 1960s at the Copacabana nightclub carousing with women. Henry starts dating Karen Friedman, a Jewish woman who is initially troubled by Henry’s criminal activities. Seduced by Henry’s glamorous lifestyle, she marries him despite her parents’ disapproval.

In 1970, Billy Batts, a made man in the Gambino crime family recently released from prison, patronizes Tommy at a nightclub owned by Henry; Tommy and Jimmy beat, stab and fatally shoot Billy. The unsanctioned murder of a made man invites retribution; realizing this, Jimmy, Henry, and Tommy bury the body in upstate New York. Six months later, however, Jimmy learns that the burial site is slated for development, prompting them to exhume and relocate the decomposing corpse.

In 1974, Henry witnesses Tommy murder Spider, an errand boy, after exchanging insults with him during a card game. Karen discovers Henry has a mistress and threatens him at gunpoint. Henry moves in with his mistress, but Paulie insists that he should return to Karen after collecting a debt from a gambler in Tampa with Jimmy. Upon returning, Jimmy and Henry are arrested after being turned in by the gambler’s sister, an FBI typist, and they receive ten-year prison sentences. To support his family on the outside, Henry has Karen smuggle in drugs and sells them to a fellow inmate from Pittsburgh.

In 1978, Henry is paroled and expands his cocaine business with Jimmy and Tommy against Paulie’s orders. Jimmy organizes a crew to raid the Lufthansa vault at John F. Kennedy International Airport, stealing six million dollars in cash and jewelry. After some members purchase expensive items against Jimmy’s orders and the getaway truck is found by police, he has most of the crew (except Tommy and Henry) murdered. In 1979, Tommy is deceived into believing he is to become a made man and is murdered after walking into the room of the ceremony—partly as retribution for murdering Batts.

By 1980, Henry develops a drug habit and becomes a paranoid wreck. He sets up another drug deal with his Pittsburgh associates, but he is arrested by narcotics agents and incarcerated. After bailing him out, Karen reveals that she flushed $60,000 worth of cocaine down the toilet to prevent FBI agents from finding it during their raid, leaving them penniless. Feeling betrayed by Henry’s drug dealing, Paulie gives him $3,200 and ends their association. Karen goes to Jimmy for help, but eventually flees upon suspecting a trap to murder her. Henry later meets Jimmy at a diner and is asked to travel on a hit assignment, but the novelty of such a request makes Henry suspicious. Realizing that Jimmy also plans to have him killed, Henry finally decides to become an informant and enroll, with his family, into the witness protection program. Henry gives sufficient testimony and evidence in court to have Paulie and Jimmy convicted, and moves to a nondescript neighborhood, unhappy to leave his exciting gangster life to live as a boring, average «schnook».

The end title cards state that (as of 1990, when the film was released) Henry is still a protected witness but that he was arrested in 1987 in Seattle for narcotics conspiracy. Henry received five years of probation but has since been clean. He and Karen separated in 1989, and Paulie died the previous year in Fort Worth Federal Prison from respiratory illness. Jimmy is serving a 20 years-to-life sentence in a New York prison for murder and would be eligible for parole in 2004.

Cast[edit]

- Robert De Niro as James Conway[7]

- Ray Liotta as Henry Hill

- Joe Pesci as Tommy DeVito

- Lorraine Bracco as Karen Hill

- Paul Sorvino as Paul Cicero[7]

- Frank Sivero as Frankie Carbone

- Tony Darrow as Sonny Bunz

- Mike Starr as Frenchy

- Frank Vincent as Billy Batts

- Chuck Low as Morris Kessler

- Frank DiLeo as Tuddy Cicero

- Henny Youngman as Himself

- Gina Mastrogiacomo as Janice Rossi

- Catherine Scorsese as Tommy’s mother

- Charles Scorsese as Vinnie

- Suzanne Shepard as Karen’s mother

- Debi Mazar as Sandy

- Margo Winkler as Belle Kessler

- Welker White as Lois Byrd

- Jerry Vale as Himself

- Julie Garfield as Mickey Conway

- Christopher Serrone as Young Henry

- Elaine Kagan as Henry’s mother

- Beau Starr as Henry’s father

- Kevin Corrigan as Michael Hill

- Michael Imperioli as Spider

- Robbie Vinton as Bobby Vinton

- John Williams as Johnny Roastbeef

- Illeana Douglas as Rosie

- Frank Pellegrino as Johnny Dio

- Tony Sirico as Tony Stacks

- Samuel L. Jackson as Stacks Edwards

- Paul Herman as Dealer

- Edward McDonald as Himself

- Louis Eppolito as Fat Andy

- Tony Lip as Frankie the Wop

- Anthony Powers as Jimmy Two Times

- Vinny Pastore as Man w/Coatrack

- Tobin Bell as Parole Officer

- Isiah Whitlock Jr. as Doctor

- Richard «Bo» Dietl as Arresting Narc

- Ed Deacy as Detective Deacy

- Victor Colicchio as Henry’s 60’s crew

- Vincent Gallo as Henry’s 70’s crew

- Joseph Bono as Mikey Franzese

- Katherine Wallach as Diane

- Bob Golub as Truck Driver at Diner

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Martin Scorsese, the director of the film, in 2006

Goodfellas is based on New York crime reporter Nicholas Pileggi’s book Wiseguy.[8] Martin Scorsese did not intend to make another mob film, but he saw a review of Pileggi’s book, which he then read while working on the set of The Color of Money in 1986.[9][10] He had always been fascinated by the mob lifestyle and was drawn to Pileggi’s book because he thought it was the most honest portrayal of gangsters he had ever read.[11] After reading the book, Scorsese knew what approach he wanted to take, «To begin Goodfellas like a gunshot and have it get faster from there, almost like a two-and-a-half-hour trailer. I think it’s the only way you can really sense the exhilaration of the lifestyle, and to get a sense of why a lot of people are attracted to it.»[12] According to Pileggi, Scorsese cold-called the writer and told him, «I’ve been waiting for this book my entire life,» to which Pileggi replied, «I’ve been waiting for this phone call my entire life.»[13][14]

Scorsese decided to postpone making the film when funds materialized in 1988 to make The Last Temptation of Christ. He was drawn to the documentary aspects of Pileggi’s book. «The book [Wiseguy] gives you a sense of the day-to-day life, the tedium, how they work, how they take over certain nightclubs, and for what reasons. It shows how it’s done.»[13] He saw Goodfellas as the third film in an unplanned trilogy of films that examined the lives of Italian Americans «from slightly different angles.»[15] He has often described the film as «a mob home movie» that is about money, because «that’s what they’re really in business for.»[11] Two weeks in advance of the filming, the real Henry Hill was paid $480,000.[16]

Screenplay[edit]

Scorsese and Pileggi collaborated on the screenplay, and over the course of the 12 drafts it took to reach the ideal script, the reporter realized «the visual styling had to be completely redone… So we decided to share credit.»[13][16] They chose the sections of the book they liked and put them together like building blocks.[2] Scorsese persuaded Pileggi that they did not need to follow a traditional narrative structure. The director wanted to take the gangster film and deal with it episode by episode, but start in the middle and move backwards and forwards. Scorsese compacted scenes, realizing that, if they were kept short, «the impact after about an hour and a half would be terrific.»[2] He wanted to do the voiceover like the opening of Jules and Jim (1962) and use «all the basic tricks of the New Wave from around 1961.»[2] The names of several real-life gangsters were altered for the film: Tommy «Two Gun» DeSimone became the character Tommy DeVito; Paul Vario became Paulie Cicero, and Jimmy «The Gent» Burke was portrayed as Jimmy Conway.[16] Scorsese initially titled the film Wise Guy, but later, he and Pileggi decided to change the title of their film to Goodfellas because two contemporary projects, the 1986 Brian De Palma film Wise Guys and the 1987–1990 TV series Wiseguy, had used similar titles.[2]

Casting[edit]

Once Robert De Niro agreed to play Jimmy Conway, Scorsese was able to secure the money needed to make the film.[10] Ray Liotta, who played Henry Hill, had read Pileggi’s book when it came out and was fascinated by it. A couple of years afterward, his agent told him Scorsese was going to direct a film adaptation. In 1988, Liotta met Scorsese over a period of a couple of months and auditioned for the film.[11] He campaigned aggressively for a role, though the studio wanted a well-known actor; he later said, «I think they would’ve rather had Eddie Murphy than me.»[17] The director cast Liotta after De Niro saw him in Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild (1986); Scorsese was surprised by «his explosive energy» in that film.[15] Al Pacino[18] and John Malkovich were considered for the role of Conway, and Sean Penn, Alec Baldwin, Val Kilmer, and Tom Cruise were considered for the role of Hill.[19][20][21]

To prepare for the role, De Niro consulted with Pileggi, who had research material that had been discarded while writing the book.[22] De Niro often called Hill several times a day to ask how Burke walked, held his cigarette, and so on.[23][24] Driving to and from the set, Liotta listened to FBI audio cassette tapes of Hill, so he could practice speaking like his real-life counterpart.[24] Madonna was considered for the role of Karen Hill.[19] To research her role, Lorraine Bracco tried to get close to a mob wife but was unable to, because they exist in a very tight-knit community. She decided not to meet the real Karen, saying she «thought it would be better if the creation came from me. I used her life with her parents as an emotional guideline for the role.»[25] Paul Sorvino had no problem finding the voice and walk of his character, but found it challenging finding what he called «that kernel of coldness and absolute hardness that is antithetical to my nature except when my family is threatened.»[26]

Former EDNY prosecutor Edward A. McDonald appeared in the film as himself, re-creating the conversation he had with Henry and Karen Hill about joining the Witness Protection Program. McDonald, who was friends with Pileggi, was cast on a whim; while a location scout was taking pictures of his office, McDonald casually remarked that he would be happy to play himself if needed. Pileggi called him an hour later asking if he was serious, and he was cast. The scene was unscripted, with McDonald improvising the line referring to Karen as a «babe-in-the-woods.»[27]

Photography[edit]

The film was shot on location in Queens, New York state, New Jersey, and parts of Long Island during the spring and summer of 1989, with a budget of $25 million.[16] Scorsese broke the film down into sequences and storyboarded everything because of the complicated style throughout. The filmmaker stated, «[I] wanted lots of movement and I wanted it to be throughout the whole picture, and I wanted the style to kind of break down by the end, so that by [Henry’s] last day as a wise guy, it’s as if the whole picture would be out of control, give the impression he’s just going to spin off the edge and fly out.»[9] He added that the film’s style comes from the first two or three minutes of Jules and Jim (1962): extensive narration, quick edits, freeze frames, and multiple locale switches.[12] It was this reckless attitude towards convention that mirrored the attitude of many of the gangsters in the film. Scorsese remarked, «So if you do the movie, you say, ‘I don’t care if there’s too much narration. Too many quick cuts?—That’s too bad.’ It’s that kind of really punk attitude we’re trying to show.»[12] He adopted a frenetic style to almost overwhelm the audience with images and information.[2] He also put plenty of detail in every frame because he believed the gangster life is so rich. Freeze-frames were used because Scorsese wanted images that stopped «because a point was being reached» in Henry’s life.[2]

Joe Pesci did not judge his character but found the scene where he kills Spider for talking back to his character hard to do, because he had trouble justifying the action until he forced himself to feel the way Tommy did.[11] Bracco found the shoot to be an emotionally difficult one because it was such a male-dominated cast, and she realized if she did not make her «work important, it would probably end up on the cutting room floor.»[11] When it came to the relationship between Henry and Karen, Bracco saw no difference between an abused wife and her character.[11]

According to Pesci, improvisation and ad-libbing came out of rehearsals wherein Scorsese let the actors do whatever they wanted. He made transcripts of these sessions, took the lines the actors came up with that he liked best, and put them into a revised script that the cast worked from during principal photography.[22] For example, the scene where Tommy tells a story and Henry is responding to him—the «Funny how? Do I amuse you?» scene—is based on an actual event that Pesci experienced. Pesci was working as a waiter when he thought he was making a compliment to a mobster by saying he was «funny»; however, the comment was not taken well.[28][29] It was worked on in rehearsals where he and Liotta improvised, and Scorsese recorded four to five takes, rewrote their dialogue, and inserted it into the script.[30] The dinner scene with Tommy’s mother was largely improvised. Her painting of the bearded man with the dogs was based on a photograph from National Geographic magazine.[31] The cast did not meet Henry Hill until a few weeks before the film’s premiere. Liotta met him in an undisclosed city; Hill had seen the film and told the actor that he loved it.[11]

The long tracking shot through the Copacabana nightclub came about because of a practical problem: the filmmakers could not get permission to go in the short way, and this forced them to go round the back.[2] Scorsese decided to film the sequence in one unbroken shot in order to symbolize that Henry’s entire life was ahead of him, commenting, «It’s his seduction of her [Karen] and it’s also the lifestyle seducing him.»[2] This sequence was shot eight times.[30]

Henry’s last day as a wise guy was the hardest part of the film for Scorsese to shoot because he wanted to properly show Henry’s state of anxiety, paranoia, and racing thoughts caused by cocaine and amphetamines intoxication.[2] In an interview with movie critic Mark Cousins, Scorsese explained the reason for Pesci shooting at the camera at the end of the film, «well that’s a reference right to the end of The Great Train Robbery, that’s the way that ends, that film, and basically the plot of this picture is very similar to The Great Train Robbery. It hasn’t changed, 90 years later, it’s the same story, the gun shots will always be there, he’s always going to look behind his back, he’s gotta have eyes behind his back, because they’re gonna get him someday.» The director ended the film with Henry regretting that he is no longer a wise guy, about which Scorsese said, «I think the audience should get angry at him and I would hope they do—and maybe with the system which allows this.»[2]

Post-production[edit]

Scorsese wanted to depict the film’s violence realistically, «cold, unfeeling and horrible. Almost incidental.»[10] However, he had to remove 10 frames of blood to ensure an R rating from the MPAA.[15] With a budget of $25 million, Goodfellas was Scorsese’s most expensive film to that point but still only a medium-sized budget by Hollywood standards. It was also the first time he was obliged by Warner Bros. to preview the film. It was shown twice in California, and a lot of audiences were «agitated» by Henry’s last day as a wise guy sequence. Scorsese argued that that was the point of the scene.[2] Scorsese and the film’s editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, made this sequence faster with more jump cuts to convey Henry’s drug-addled point of view. In the first test screening there were 40 walkouts in the first ten minutes.[30] One of the favorite scenes for test audiences was the «Do I amuse you?» scene.[2]

Soundtrack[edit]

While there is no incidental score as such in the film, Scorsese chose songs for the soundtrack that he felt obliquely commented on the scene or the characters.[15] In a given scene, he used only music contemporary to or older than the scene’s setting. According to Scorsese, a lot of non-dialogue scenes were shot to playback. For example, he had «Layla» by Derek and the Dominos playing on the set while shooting the scene where the dead bodies are discovered in the car, dumpster, and meat truck. Sometimes, the lyrics of songs were put between lines of dialogue to comment on the action.[2] Some of the music Scorsese had written into the script, while other songs he discovered during the editing phase.[30]

Release[edit]

Theatrical[edit]

Goodfellas premiered at the 47th Venice International Film Festival, where Scorsese received the Silver Lion award for best director.[32] It was given a wide release in North America on September 21, 1990.

Home media[edit]

Goodfellas was released on DVD in March 1997, in a single-disc, double-sided, single-layer format that requires the disc to be flipped during viewing; in 2004, Warner Home Video released a two-disc, dual-layer version, with remastered picture and sound, and bonus materials such as commentary tracks.[33] In early 2007, the film became available on single Blu-ray with all the features from the 2004 release; an expanded Blu-ray version was released on February 16, 2010, for its 20th anniversary,[34] bundled with a disc with features that include the 2008 documentary Public Enemies: The Golden Age of the Gangster Film.[33] On May 5, 2015, a 25th anniversary edition was released.[35] The film was released on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray on December 6, 2016.[36]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Goodfellas grossed $6.3 million from 1,070 theaters in opening weekend, topping the box office.[37] In its second weekend the film made $5.9 million from 1,291 theaters, falling just 8% and finishing second behind newcomer Pacific Heights.[38] It went on to make $46.8 million domestically.[39][3]

Critical response[edit]

According to review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, 96% of 107 critics have given the film a positive review, with an average rating of 9.00/10. The website’s critics consensus reads, «Hard-hitting and stylish, GoodFellas is a gangster classic—and arguably the high point of Martin Scorsese’s career.»[40] Metacritic has assigned the film a weighted average score of 90 out of 100 based on reviews from 21 critics, indicating «universal acclaim».[41] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of «A−» on an A+ to F scale.[42]

In his review for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert gave the film a full four stars and wrote, «No finer film has ever been made about organized crime – not even The Godfather.»[43] In his review for the Chicago Tribune, Gene Siskel wrote, «All of the performances are first-rate; Pesci stands out, though, with his seemingly unscripted manner. GoodFellas is easily one of the year’s best films.»[44] Both named it as the best film of 1990. In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote, «More than any earlier Scorsese film, Goodfellas is memorable for the ensemble nature of the performances… The movie has been beautifully cast from the leading roles to the bits. There is flash also in some of Mr. Scorsese’s directorial choices, including freeze frames, fast cutting and the occasional long tracking shot. None of it is superfluous.»[45] USA Today gave the film four out of four stars and called it, «great cinema—and also a whopping good time.»[12] David Ansen, in his review for Newsweek magazine, wrote «Every crisp minute of this long, teeming movie vibrates with outlaw energy.»[46] Rex Reed said, «Big, rich, powerful and explosive. One of Scorsese’s best films! Goodfellas is great entertainment.»[47] In his review for Time, Richard Corliss wrote, «So it is Scorsese’s triumph that GoodFellas offers the fastest, sharpest 2½-hr. ride in recent film history.»[48]

Lists[edit]

The film was ranked the best of 1990 by Roger Ebert,[49] Gene Siskel,[49] and Peter Travers.[50] In a poll of 80 film critics, «Goodfellas» was named the best film of the year by 34 critics. Director Martin Scorsese was chosen as the year’s best director in 45 of the 80 ballots.[51]

Goodfellas is ranked No. 92 on the AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) list, published in 2007. In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed Goodfellas as the fifteenth best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its membership.[52] In the 2012 Sight & Sound polls, it was ranked the 48th-greatest film ever made in the directors’ poll.[53] Goodfellas is 39th on James Berardinelli’s 2014-made list of the top 100 films of all time.[54] In 2015, Goodfellas ranked 20th on BBC’s «100 Greatest American Films» list, voted on by film critics from around the world.[55]

Accolades[edit]

It became one of the seven films to win Best Picture from three out of four major U.S. film critics’ groups (LA, NBR, NY, NSFC) along with Nashville, All the President’s Men, Terms of Endearment, Pulp Fiction, The Hurt Locker, and Drive My Car.

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Award | Best Picture[56] | Irwin Winkler | Nominated |

| Best Director[56] | Martin Scorsese | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor[56] | Joe Pesci | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress[56] | Lorraine Bracco | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay[56] | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing[56] | Thelma Schoonmaker | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Award | Best Motion Picture – Drama[57] | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Nominated |

| Best Director[57] | Martin Scorsese | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor[57] | Joe Pesci | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress[57] | Lorraine Bracco | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay[57] | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Won | |

| Best Actor | Robert De Niro | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Thelma Schoonmaker | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Richard Bruno | Won | |

| Directors Guild of America Award | Outstanding Directing – Feature | Martin Scorsese | Nominated |

| Writers Guild of America Award | Best Adapted Screenplay | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Nominated |

| César Award | Best Non-French Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Nominated |

| Venice Film Festival | Silver Lion for Best Director[58] | Martin Scorsese | Won |

| Audience Award | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Filmcritica «Bastone Bianco» Award | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Actor | Robert De Niro | Won | |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Joe Pesci | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Lorraine Bracco | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus | Won | |

| National Board of Review Award | Best Supporting Actor | Joe Pesci | Won |

| Boston Society of Film Critics Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Joe Pesci | Won | |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Joe Pesci | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Lorraine Bracco | Won | |

| Best Screenplay | Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi | Won | |

| National Society of Film Critics Award | Best Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

| Best Director | Martin Scorsese | Won | |

| Bodil Award | Best American Film | Martin Scorsese and Irwin Winkler | Won |

Legacy[edit]

Goodfellas is No. 94 on the American Film Institute’s «100 Years, 100 Movies» list and moved up to No. 92 on its AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) from 2007. In June 2008, the AFI put Goodfellas at No. 2 on their AFI’s 10 Top 10—the best ten films in ten «classic» American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the movie-related community.[59] Goodfellas was regarded as the second-best in the gangster film genre (after The Godfather).[60] In 2000, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film «culturally significant» and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Roger Ebert named Goodfellas the «best mob movie ever» and placed it among the ten best films of the 1990s.[61] In December 2002, a UK film critics poll in Sight & Sound ranked the film No. 4 on their list of the 10 Best Films of the Last 25 Years.[62] Time included Goodfellas in their list of Time’s All-Time 100 Movies.[63] Channel 4 placed Goodfellas at No. 10 in their 2002 poll The 100 Greatest Films, Empire listed Goodfellas at No. 6 on their «500 Greatest Movies Of All Time,»[64] and Total Film voted Goodfellas No. 1 as the greatest film of all time.[65]

Premiere listed Joe Pesci’s Tommy DeVito as No. 96 on its list of «The 100 Greatest Movie Characters of All Time,» calling him «perhaps the single most irredeemable character ever put on film.»[66] Empire ranked Tommy DeVito No. 59 in their «The 100 Greatest Movie Characters» poll.[67]

Goodfellas inspired director David Chase to make the HBO television series The Sopranos.» He told Peter Bogdanovich, «Goodfellas is a very important movie to me and Goodfellas really plowed that … I found that movie very funny and brutal and it felt very real. And yet that was the first mob movie that Scorsese ever dealt with a mob crew. … as opposed to say The Godfather … which there’s something operatic about it, classical, even the clothing and the cars. You know I mean I always think about Goodfellas when they go to their mother’s house that night when they’re eating, you know when she brings out her painting, that stuff is great. I mean The Sopranos learned a lot from that.»[68] Indeed, the film shares a total of 27 actors with The Sopranos,[69] including Bracco, Sirico, Imperioli, Pellegrino, Lip, and Vincent, who all had major roles in Chase’s HBO series.

July 24, 2010 marked the 20th anniversary of the film’s release. This milestone was celebrated with Henry Hill hosting a private screening for a select group of invitees at the Museum of the American Gangster, in New York City.[70]

In January 2012, it was announced that the AMC Network had put a television series version of the movie in development. Pileggi was on board to co-write the adaptation with television writer-producer Jorge Zamacona. The two were set to executive produce with the film’s producer Irwin Winkler and his son, David.[71]

Luc Besson’s 2013 crime comedy film The Family features a sequence where Giovanni Manzoni (Goodfellas star De Niro), a gangster who is under witness protection for testifying against a member of his family, watches Goodfellas.[72]

In 2014, the ESPN-produced 30 for 30 series debuted Playing for the Mob,[73] the story about how Hill and his Pittsburgh associates, and several Boston College basketball players, committed the point shaving scandal during the 1978–79 season, an episode briefly mentioned in the movie. The documentary, narrated by Liotta, was set up so that the viewer needed to watch the film beforehand in order to understand many of the references in the story.

In 2015, Goodfellas closed the Tribeca Film Festival with a screening of its 25th-anniversary remaster.[74]

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movies — #94

- AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) — #92

- AFI’s 10 Top 10 — #2 Gangster film

- AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Heroes and Villains — Tommy DeVito — Nominated Villain

- AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movie Quotes — «Funny how?» — Nominated Quote

References[edit]

- ^ «Goodfellas (18)». British Board of Film Classification. September 17, 1990. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Thompson, David; Christie, Ian (1996). «Scorsese on Scorsese». Faber and Faber. pp. 150–161. ISBN 9780571178278.

- ^ a b «Goodfellas (1990) — Financial Information». The Numbers. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ «Librarian of Congress Names 25 More Films to National Film Registry». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ «Complete National Film Registry Listing». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ Merrie, Stephanie (April 29, 2015). «‘Goodfellas’ is 25. Here’s an incomplete list of all the movies that have ripped it off». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ a b «Goodfellas review – a brash, menacing hightail through the death of the mob». The Guardian. January 19, 2017. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Vlastelica, Ryan (September 18, 2015). «Goodfellas turned Wiseguy’s simple prose into cinematic gold». The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Malcolm, Derek (September–October 1990). «Made Men». Film Comment.

- ^ a b c Goodwin, Richard. «The Making of Goodfellas«. Hotdog.

- ^ a b c d e f g Linfield, Susan (September 16, 1990). «Goodfellas Looks at the Banality of Mob Life». The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Mike (September 19, 1990). «GoodFellas step from his childhood». USA Today.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Mary Pat (1991). Martin Scorsese: A Journey. Thunder’s Mouth Press. ISBN 9780938410799.

- ^ «The Making of Goodfellas». Empire Magazine. November 1990. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Gilbert, Matthew (September 16, 1990). «Scorsese Tackles the Mob». Boston Globe.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, Howard (August 22, 2006). Crime Wave: The Filmgoers’ Guide to the Great Crime Movies. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-1845112196.

- ^ Portman, Jamie (October 1, 1990). «Goodfellas Star Prefers Quiet Life». Toronto Star.

- ^ «50 genius facts about GoodFellas». Shortlist. February 11, 2011.

- ^ a b «Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas: A Complete Oral History». gq.com. September 20, 2010.

- ^ «Alec Baldwin auditioned to play Henry Hill in ‘Goodfellas’«. Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Caulfield, Rachel Maresca, Philip. «‘Goodfellas’ at 25: Here are 25 things you never knew about Martin Scorsese’s mobster flick». New York Daily News.

- ^ a b Arnold, Gary (September 25, 1990). «Real Fellas Talk about Mob Film». The Washington Times.

- ^ Wolf, Buck (November 8, 2005). «Rap Star 50 Cent Joins Movie Mobsters». ABC News. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ^ a b Papamichael, Stella (October 22, 2004). «GoodFellas: Special Edition DVD (1990)». BBC. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ^ Witchel, Alex (September 27, 1990). «A Mafia Wife Makes Lorraine Bracco a Princess». The New York Times.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (October 12, 1990). «At the Movies». The New York Times.